Amateur Photographer verdict

An awesome camera: not so much an expensive APS-C camera as a pro camera with an APS-C sensor, the Nikon D500 remains unrivalled used as a conventional DSLR for shooting fast-moving subjects.- Remarkable autofocus system

- Fine image quality at both low and high ISO settings

- Excellent build quality and handling

- Large and heavy compared to APS-C peers

- Much less capable when used in live view

- 20.9-megapixel resolution

The Nikon D500 was Nikon’s fastest APS-C Digital SLR, and could be one of the best DSLRs available anywhere – especially for fast-lane photography – think wildlife, action, sports etc. Find out how it performs in our full review.

Nikon D500 – At a glance

- 20.9 MP DX CMOS sensor

- from $700 – $1,600 / £700 – £850 – used body only

- 153-point phase detection AF System

- Nikon F-mount

- ISO 100- 51,200 (standard)

- Records up to 4K UHD 40fps; Full HD 60fps

What is the Nikon D500?

The Nikon D500 was Nikon’s fastest, most rugged and most powerful APS-C DSLR. It’s almost impossible to find new these days, but plenty of examples exist on the used market, with good examples of moderate use and wear for under $1,000 in the US, £1,000 in the UK. Beware of high shutter counts when shopping for used cameras. The D500 was rated at 200,000, but you can still find models with a relatively low shutter count. But is it still worth buying and spending money on? Read on to find out…

Although officially discontinued, the D500 is still surprisingly effective, at least for stills photography. Many photographers prefer the optical viewfinder of a DSLR over the EVF of a mirrorless camera, especially for sports photography. High-speed shooting, and the D500’s continuous shooting and professional-level raw buffer capacity are still reasons to consider it today. The D500 is also backed up by a huge range of Nikon DX and FX lenses.

History

Back in 2007, Nikon unleashed a pair of DSLRs that revitalised its line-up and re-established the company as being at least on par with its rival Canon. The professional-level Nikon D3 was its first full-frame model, with super-fast shooting and an impressive 51-point AF system.

Meanwhile, the DX-format Nikon D300 was very much a D3-lite, offering many of the flagship’s best features in a smaller body at a fraction of the price. It rapidly won the hearts of a generation of serious enthusiasts and semi-professional photographers, spurring Canon to produce a decent competitor with the Canon EOS 7D.

The D300 underwent a relatively minor refresh with the Nikon D300S in 2009. After that, Nikon seemed insistent that its D7000-series of enthusiast-focused DSLRs met the needs of most enthusiasts. But in 2016 Nikon relented and, just in time for a summer of European Championship football and the Olympic Games, produced a genuine successor in the shape of the D500, alongside the professional Nikon D5, with an astonishing set of specifications that still impress today.

These include an extended top ISO of 1.6 million, alongside a 153-point AF system and 10fps continuous burst shooting. On paper, it’s the best APS-C DSLR so far, and with the end of DSLR production it’s not likely to be surpassed. To find out more, see our guide to the best Nikon DSLRs and also the best Nikon F-mount lenses.

Of course, the D500 is now competing with mirrorless cameras that can shoot faster bursts, better video and higher resolution stills. Examples include the Fujifilm X-H2S, Canon EOS R7 and OM System OM-1. So with this in mind, just how good does the Nikon D500 look today?

Nikon D500 review – Features

A quick glance at the D500’s key specs reveal a remarkably well-featured camera. Its 20.9-million-pixel DX-format sensor affords an impressive standard sensitivity range of ISO 100-51,200, and a frankly staggering extended range of ISO 50-1,640,000. It can shoot at 10fps, and keep going for at least 30 frames in raw format and 90 or more in JPEG mode. That’s with an SD card; place an XQD card in the second slot, and it’ll keep shooting at full speed for 200 frames in raw.

Since the D500’s launch, the XQD format has practically disappeared, but a subsequent firmware update has made the camera compatible with the newer and now widely used (and physically identical) CFexpress Type B format. The most up-to-date firmware update (“C” firmware to version 1.31) is available to download from Nikon.com.

The 20.9-megapixel resolution is a small drop from Nikon’s previous 24-megapixel models, but it’s the same resolution as OM System cameras, most Panasonic Lumix models and even the mighty Canon EOS R6 (Mark 1).

Autofocus uses a 153-point system covering almost the full width of the frame and around half its height, while metering employs a 180,000 pixel RGB sensor that also feeds subject-recognition data to the AF system. Nikon specifies that both systems will work in awfully low light: -3EV for metering, and -4EV for AF. That AF sensitivity, while remarkable for its time and still terrific today, has been improved on by newer mirrorless cameras.

Video

The D500 is also capable of recording 4K video, but with the catch that it uses a 1.5x crop in the centre of the frame, compromising wideangle shooting. Full HD movies can be captured at up to 60fps; this time with a recording area the full width of the sensor. But while it has some nice movie-friendly features, including microphone and headphone sockets, and a flat picture profile, there’s no focus-peaking display and only rudimentary zebra pattern overexposure warning.

This 1.5x crop in particular limits the Nikon’s appeal for filmmakers. Technically it does shoot 4K, but you would probably choose any one of a dozen modern mirrorless cameras in preference to this one for 4K video.

One thing the D500 lacks is a built-in flash, and users will instead have to rely on hotshoe-mounted external units. This will disappoint anyone planning to use Nikon’s excellent wireless flash system, but it reinforces the camera’s positioning as an available light action specialist. Presumably, Nikon believes portrait photographers would be better off with a D750.

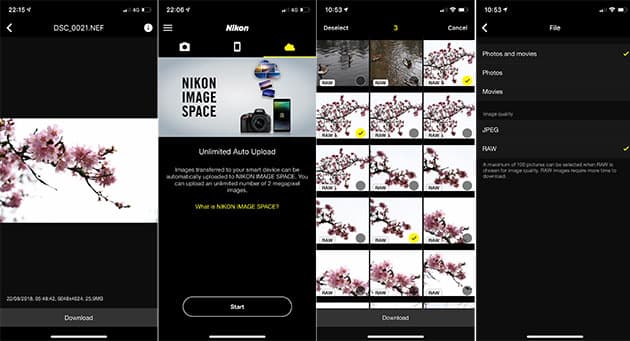

SnapBridge

A new feature that Nikon is trumpeting is its SnapBridge connection to smartphones or tablets. Maintaining a permanent connection between the camera and smart device using Bluetooth is designed to get around the limitations of current Wi-Fi implementations. It switches to the more power-hungry Wi-Fi only when required for transferring high-resolution images or remotely controlling the camera. Part of the idea is that the camera can automatically transfer every picture you take to your phone (and then to Nikon’s cloud-sharing service, if you like) without needing the Wi-Fi turned on all the time.

This sounds great, but sadly, at the time of our original review, it didn’t work very well. On Android devices, SnapBridge did function pretty much as advertised, but even a brief play revealed it to be less suited to a high-end camera like the D500. Most obviously, the remote-control app offered no manual settings changes at all – a perplexing oversight at a time when every other brand offers extensive manual control of the camera via Wi-Fi.

The connection between the camera and phone is always active, even when the camera’s power switch is set to off. But contrary to the idea of using Bluetooth, this can result in considerable battery drain on the camera even when it is switched off. This can be fixed by switching the camera to its airplane mode, if you can find it in the menu and remember to turn it on. But then the two devices can often fail to re-establish the connection when you need it.

Build and handling

As we’d expect from a professional sports camera, the D500 gives the impression of being built like a tank. The magnesium-alloy body has a bombproof feel to it, and a well-designed grip means that it fits perfectly in the hand. Almost every square inch of the body is covered by buttons and dials, which give direct access to all the key functions – so much so, that there’s rarely any need to access the menus.

Nikon has used broadly the same control layout as that on recent models, such as the D810, but added a few additional tweaks that come straight out of the Canon playbook: at long last there’s a sensibly placed ISO button immediately behind the shutter release, and a joystick for positioning the focus point that sits naturally under the right thumb. Pressing this inwards engages autoexposure lock, and if you prefer using the D-pad to move the focus point, this works, too.

The upshot is that the most important settings can all be changed without taking the camera from your eye while shooting. However, those accessed from the cluster on the left-side top-plate – including drive mode, metering, white balance and exposure mode – still require you to remove your left hand from supporting the lens.

Nikon also offers a decent level of customisation, so you can reassign various buttons to suit your personal shooting. But to be honest, the basic layout is so well worked out that you might not find much need for this.

Unsurprisingly for such a sophisticated camera, the D500’s menus are complex, even for a seasoned user. It’s not so hard to work out what each option does when browsing through them at leisure, but trying to find and change any specific setting in a hurry is a real trial. Because of this, it makes a lot of sense to place your most needed functions in the customisable ‘My Menu’ once you get to know the camera.

It’s worth mentioning one thing that has become apparent with the rise of mirrorless cameras. It’s true that the D500 is bigger and bulkier by comparison, but for sports and wildlife fans using longer lenses, this can actually make it better balanced and easier to handle. Many mirrorless cameras suffer from having a small body married up to big lenses.

Viewfinder and screen

Without doubt, the D500’s optical viewfinder is one of the best we’ve seen on an APS-C DSLR. With a magnification of 1.0x and 100% coverage of the image area, it’s certainly the largest, and not far off full-frame DSLRs or the electronic viewfinders on high-end mirrorless cameras in terms of size. It doesn’t have all the clever viewfinder information overlays that Canon has included on its EOS 7D Mark II, but you do get to see all the core exposure data along with gridlines and a twin-axis electronic level. Unfortunately, this is usually displayed in black, so it can be difficult to discern while shooting.

The 2.36-million-dot rear screen is superb – it’s impressively detailed, while giving accurate colour rendition. Its ability to tilt 90° upwards or downwards can be handy in some situations for shooting from odd angles, although there is no doubt that the D500 is vastly more competent when using the viewfinder compared to shooting in live view.

Nikon has made the screen touch-sensitive, but kept the touch functionality to a minimum. You can select the focus point by touch in live view and movie modes, release the shutter and browse images in playback. But you can’t use the screen to browse menus or change any settings. This isn’t a deal-breaker, but would certainly have been useful, especially for video use.

Autofocus

At the D500’s heart is its 153-point autofocus system, which is very similar to that used in the flagship D5. Indeed, it’s the camera’s raison d’être, with Nikon aiming to give photographers a significant fraction of the D5’s capabilities in a smaller, cheaper package.

The first thing you notice on looking through the viewfinder is the huge spread of those focus points, covering the full width of the frame and a significant fraction of its height. It’s not quite the whole-frame coverage that we’ve become used to from mirrorless cameras, but is significantly greater than what you’ll get from any other DSLR.

Nikon has recognised that navigating so many focus points would be impractical, so it has limited the user-selectable array to 55, with the remainder employed to assist focus tracking on moving subjects. Indeed, these are so densely packed that there’s little chance of your subject drifting into an area that’s not covered.

If the subject is static, then you can shoot with either a single point or a group of points, which can be helpful with some subjects to avoid focusing on the background. For continuous focus on a moving subject, you have a number of extra options to choose from. Dynamic group mode is most effective when you know roughly where the subject will be in the frame; you can instruct the camera to use 25, 72, or all 153 focus points to maintain focus. Alternatively, in 3D tracking mode the camera uses all 153 points to follow the subject as it moves around the frame, with the 180,000-pixel metering sensor feeding information to help the camera keep track of your main subject.

There’s little doubt that the D500, alongside the D5, represents current state-of-the-art autofocus and subject tracking, keeping your subject sharp with uncanny ease, no matter how it moves around. If this is something you need – for sports, wildlife, or simply taking pictures of erratically moving kids – no other camera is likely to do it as well, let alone better.

Switch the camera to live view, though, and its AF speed falls off a cliff. Its contrast-detection system is tolerable for handheld shooting, but is not a patch on the lightning-fast systems on modern mirrorless cameras. The Nikon D780 was the first and only Nikon DSLR to offer on-sensor phase-detect AF, but it looks unlikely that Nikon will release another. However, the D500’s live view does at least benefit from the inherent accuracy of contrast-detection AF, especially when using fast lenses to shoot off-centre subjects.

Performance

As for metering, four patterns are available – matrix, centreweighted, spot and highlight weighted. The default matrix system is very strongly biased towards ‘correct’ exposure of whatever is under the active AF area, regardless of whether this suits the scene as a whole. This approach has it merits, but does have a certain tendency to clip highlights in high-contrast scenes. In such situations I appreciated having the highlight-weighted option which, as its name suggests, aims to maintain highlight detail, allowing you to bring up shadow regions in post-processing.

In this regard, raw files are remarkably malleable at low-ISO sensitivities, and it’s possible to pull vast amounts of detail out of the shadows without it being blighted by excessive noise. JPEG shooters can use Nikon’s Active D-Lighting feature to make similar use of the sensor’s superb dynamic range.

Auto white balance (AWB) tends to give extremely neutral results – indeed, too much for my tastes. For example, it’s prone to removing attractive warm casts from sunlit scenes, and I usually prefer to add back a little warmth to my images in post-processing. But while the AWB setting can be changed in the menu to retain warmth under artificial light, there’s no such option for daylight shooting.

Nikon’s colour rendition is generally very appealing, giving rich, saturated colours without going over the top. The output can be adjusted from the Picture Control menu using a range of subject-based settings, all of which can be individually fine-tuned. Sports and action shooters are likely to spend a lot of time using JPEGs, so it’s good to see that Nikon offers high-quality results straight from the camera.

Overall image quality is very good, but then again the same is true of much cheaper Nikon APS-C DSLRs. Indeed, at low ISOs there’s no real advantage in this area compared to the Nikon D7200 or indeed the D5500. But the D500 keeps going longer as the ISO is raised, and so long as you don’t expect miracles, it’s still capable of giving quite usable files at its top standard setting of ISO 51,200, and maybe even a stop higher. However, I can’t help but think that the extended settings exist more for marketing value than practical use.

Dynamic range, resolution and noise

Nikon used a 20.9-million-pixel DX-format sensor in the D500, and it delivers impressive image quality. It’s lower in resolution than Nikon’s cheaper DX DSLRs, which sport 24-million-pixel sensors, but the difference is less than 10% in terms of linear resolution, and I suspect it will be easy to accept this compromise in return for the D500’s other considerable skills. More to the point, high ISO performance is very good indeed, with the top standard sensitivity of ISO 51,200 giving remarkably respectable results. Unfortunately, though, the extended settings do seem to be hugely over-optimistic; anyone expecting usable ISO 1,638,400 from a DX sensor will need to wait a little longer.

Dynamic range

When it comes to dynamic range, the D500 scores remarkably well in our Applied Imaging tests. At ISO 50 we have a dynamic range of over 13EV, indicating massive leeway for recovering additional details from raw files, especially in shadow regions. This drops only slowly up to ISO 800, but beyond this the curve tails off more rapidly. Even so, values of 8.3EV at ISO 6,400 and 6EV at ISO 51,200 represent a remarkably strong showing for this size of sensor. But the precipitous decline in the extended settings indicates why these have limited practical use.

Resolution

The D500 captures as much from our resolution charts as we could realistically expect from its 20.9MP sensor. At low ISOs in raw it resolves around 3,700l/ph before maze-like aliasing comes into play; the JPEG processing tends to suppress such artefacts at the expense of slightly lower resolution. But what’s more impressive is its high ISO capability, with 3,000l/ph still recorded at ISO 6,400. At the highest standard setting of ISO 51,200, it achieves 2,600l/ph, but past this things go downhill quickly. Even at ISO 204,800, we see around 2,000l/ph, but the higher extended settings are too poor to be worth reproducing here.

Noise

Both raw and JPEG images taken from our diorama scene are captured at the full range of ISO settings. The camera is placed in its default setting for JPEG images. Raw images are sharpened and noise reduction applied, to strike the best balance between resolution and noise.

At low ISO sensitivities, the D500’s image quality is superb; fine detail is rendered with impressive sharpness thanks to the lack of an optical low-pass filter, and there’s no visible noise. At ISO 800 a little luminance noise becomes visible, and shadow details start to disappear. ISO 1,600 is still eminently usable, but by the time we hit ISO 6,400 fine detail and colour saturation are visibly suffering. By ISO 51,200, colour rendition becomes very broad-brush, but the image is still entirely recognisable and should be perfectly usable with careful processing from raw; this is pretty impressive coming from an APS-C-format sensor. However, at the extended higher sensitivity settings, it’s increasingly difficult to see the point as the image disappears progressively under an ocean of noise.

Nikon D500 – Verdict

In recent years, photographers looking for a truly high-end APS-C DSLR for sports and action shooting have been more or less limited to Canon’s EOS 7D Mark II and perhaps the later EOS 90D. But with the D500, Nikon returned to this sector in fine style, and its combination of superb autofocus, fast continuous shooting and excellent image quality places it very much at the top of the list.

The D500 is arguably the most accomplished crop-sensor camera yet made. Build and handling are exemplary, aided by some well-judged tweaks to the control layout; I particularly appreciated the repositioned ISO button and the joystick AF point selector. Meanwhile, the viewfinder is excellent, and it’s nice to see a tilting rear screen on a camera of this type, although it’s perhaps less useful here than on a mirrorless camera. The addition of 4K video recording will be the icing on the cake for some users, but make no mistake, the D500 shines brightest when used as a conventional DSLR for shooting fast-moving subjects.

Indeed, in all the time I’ve spent working with the D500, I’ve been hugely impressed by its ability to pull any shot out of the bag, acquiring focus quickly and confidently no matter how erratically moving the subject or how dim the light. Its excellent high ISO capability means it will deliver entirely usable image files in extremely low light, too.

The stumbling block: the original price of the Nikon D500 was more than you would have paid for some excellent full-frame cameras, including Nikon’s own D750, and around $1,000 / £1,000 more than the next DX model down – the highly accomplished Nikon D7200. Indeed, many Nikon users eyeing an upgrade might have been better served by buying a couple of nice Nikkor lenses instead, or upgrading to full frame if they’re looking for improved image quality. For this reason, the D500’s practical appeal was originally limited to those who know for sure that they can make use of its astonishing autofocus system and impressive high ISO image quality, and appreciate the extra effective telephoto reach afforded by the DX sensor.

The fact is, the D500 is not so much an expensive APS-C camera as a pro camera with an APS-C sensor. Looked at in those terms, it makes rather more sense, especially with today’s attractive and appealing prices on the secondhand market.

Find more great DSLRs from Nikon see our guide to the best Nikon DSLRs ever.

Related reading:

- Camera head-to-head: Canon EOS 7D Mark II vs Nikon D500

- Nikon D7500 vs Nikon D500

- Best zoom lenses for Nikon DSLRs

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.