This autumn sees the launch of a major new book and exhibition devoted to examining the multiplicities of photography during 1980s Britain. Peter Dench finds out more

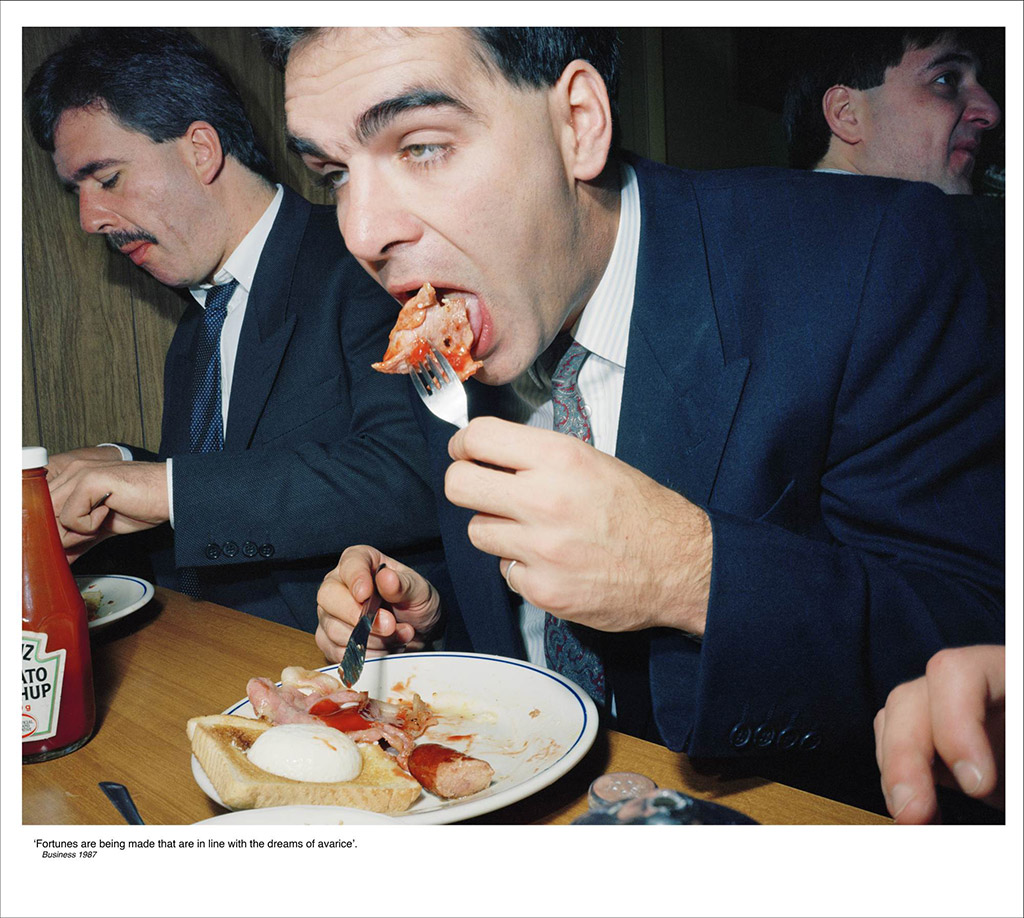

1980s Britain. A payload of nostalgia, a time bomb of memories. Football hooliganism, Acid House parties, shoulder pads, yuppies, Charles and Diana, unemployment, bewildering advertisements aimed to educate the public about HIV/AIDS and prevent its spread, economic upheaval, social tension, city-wide riots, bombings, de-industrialisation and of course, Margaret Thatcher. You’ll likely have your personal, immediately-comes-to-mind list from this divisive decade, the events of which still ricochet today.

With all seismic social, political and economic shifts there is bedfellow photography. Tate Britain has taken on the task of presenting a landmark survey which will present the decade as a pivotal moment for the medium. It’s about time for Tate to step up. Opened in 1897 and home to the world’s largest collection of works by painter JMW Turner, it only started collecting photography in the 1990s.

The concept for The 80s: Photographing Britain was sparked by Yasufumi Nakamori, then Senior Curator of International Art (Photography) at Tate (2018-2023) now Director of the Asia Society Museum, New York. Nakamori recognised the need for a show at Tate to really consider British photography on the period. Initial discussions began four to five years ago. Deep work on the exhibition two to three years ago. Two weeks from install and ephemera was still arriving, deadlines screaming. Alongside Nakamori, the exhibition is edited by Helen Little, Curator, British Art, Tate Britain and Dr Jasmine Chohan, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain. There is additional support from within Tate and discourse fed in from experts, networks, galleries and institutions across the photography world.

The Long 1980s

The exhibition is big. So big, it’s a period Tate refers to as the long 1980s, to include the years 1976-1993, just prior to and in the immediate aftermath of Thatcher’s Conservative government (1979-90). Around 350 images and archive materials, featuring 70 photographers and lens-based artists and collectives make up the show. Tate emphasises this isn’t a comprehensive depiction of the ’80s – that would be impossible.

Key starting points for the thinking about photography during this period began with journals Ten 8 (quarterly 1979-1992) and Camerawork (bi-monthly 1976–1985), the groundbreaking anthology of essays, Photography: Politics One (1979), edited by Terry Dennett and Jo Spence and the 1990 Autoportraits exhibition held at Autograph (founded in 1988 in London to support black photographic practices).

Big names featured throughout

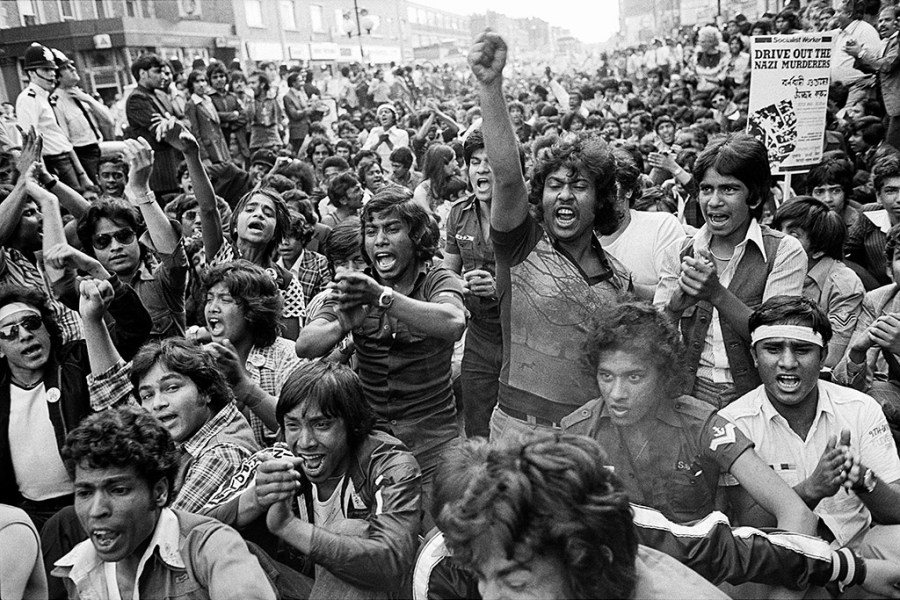

To create context and a framework for the show, it starts with an exploration of social documentary photography of significant events of the era including a look at the Grunwick Dispute, anti-racist movements (including photos by Paul Trevor, Varley Burke), the miners’ strikes (David Hoffman, John Harris), the women-only Format Photography Agency (founded in 1983) capturing of the largely female protests against nuclear weapons at Greenham Common, poll tax protests, the Troubles, reaction to Section 28 (a series of UK laws that prohibited local authorities from promoting homosexuality introduced by Thatcher’s government) and the efforts of ACT UP to raise awareness of the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

From there the show explores the cost of living and disparities mainly between the middle and working classes (Martin Parr, Tish Murtha, Markéta Luskacová, Don McCullin). The medium is then considered as artistically linked to painting, more traditional artistic forms and landscape photography (John Davies, Jem Southam, Keith Arnatt). The development of conceptual photography through image and text (Victor Burgin, Karen Knorr, Olivier Richon) and how colour developed through the 1980s to become a prominent format to photograph in (Paul Graham, Paul Reas, Peter Fraser).

Also featuring prominently is the position of black and Asian photographers in the period through reflections of the black experience (Marc Boothe, Sunil Gupta, Mumtaz Karimjee, Lyle Ashton Harris). It finishes once again on more of a social point looking at counter-culture movements, how they’ve become celebrated and how the LGBTQ movements have become more overground and overt.

The accompanying book embellishes the show, with accompanying essays by Geoffrey Batchen (Distinctly Discursive), Mark Sealy and Derek Bishton (A Critical Decade), Taous R Dahmani (Feminist Praxis), Noni Stacey (Working Together), Bilal Akkouche (Challenging the Colonial Gaze).

![[no title], 1991 ©Jason Evans](https://amateurphotographer.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2024/11/03-Jason-Evans-Simon-Foxton-no-title-1991.jpg?w=1024)

Curatorial influence

The three core curators bring their own very distinctive experiences. The show’s selection and book contributions have been informed around them. Nakomori’s exceptional bank of knowledge is applied to a chapter on Imaging Activism. Originally from the north, growing up in the ’80s and starting her career at Ikon Gallery, Helen Little contributes the essay From Today, Black and White is Dead, charting both the aesthetic and technical advancement of colour photography.

Chohan, a PhD graduate: Courtauld Institute of Art, specialising in Biennials, Contemporary Cuban art and art from the Global South, chose to write about Photographing Protests. A second-generation Punjabi Sikh who grew up in Southall, a district of west London and South Asian hub since the 1950s, often called Little Punjab or Little India, she spoke Punjabi as a first language and attended Villiers High School where 82 languages were spoken.

‘My background in art history is very politicised I would say. Politics is at the heart of a lot of what I’ve studied. I think for me it came from my connection to Southall, the anti-racist movements, a lot of my family were involved in them. The reason I wanted to focus on photographing protests was because I feel slightly jaded by politics today. Looking at the politics of the 1980s, what strikes me is there’s such hope and optimism behind these difficult and traumatic times. I wanted to highlight the way these communities pulled together in the face of such stressful, straining times and pushed for change effectively. Protest meant change was possible. Today, protest strikes me as quite performative a lot of the time. What do we change? We march every week. Where has the dial shifted?

‘In this period [1980s] so much was changed through protest. All those movements were so exceptional with such unity.’ Images from Dennis Morris bring context into lives within the Southall community.

With such an ambitious exhibition there will inevitably be omissions of historical events and contributing photographers. It would be easy to dwell on these rather than focus on what is represented, as Chohan alludes, ‘Do we wish we could have tripled the amount of work, yes. We’ve constantly been, very wisely I would say, told to trim because we don’t want to overrun viewers either or do the work a disservice because that’s the other thing we’re having to balance. How do we ensure the works that we have selected receive their due diligence and platforms as they should be? What have we missed? Why have we missed it? Realistically it’s just about what’s humanly possible to include, and what we’ve prioritised are the more marginalised movements and marginalised photographers.’

She continues, ‘One way we’re trying to ensure people feel heard and seen is by not positioning the curators’ voice at the heart of the exhibition and actually using the voices of photographers, using the voices of people who were in this period whether it’s participants in these protests or the communities or part of it or the photographers themselves. A lot of the captions are direct quotes from photographers. It brings history closer to us and makes it real.’

No documentary photograph is entirely objective but those of the 1980s are arguably more so than today’s increasingly manipulated images and narratives. The 80s: Photographing Britain weaves together multiple perspectives from innovative publications, collectives, independent galleries and the work of photographers giving the viewer room to analyse, compare and make their own interpretations on the breadth of work on display.

List of artists

Keith Arnatt; Derek Bishton; Sutapa Biswas; Tessa Boffin; Marc Boothe; Victor Burgin; Vanley Burke; Pogus Caesar; Thomas Joshua Cooper; John Davies; Poulomi Desai; Al-An deSouza; Willie Doherty; Jason Evans; Rotimi Fani-Kayode; Anna Fox; Simon Foxton; Armet Francis; Peter Fraser; Melanie Friend; Paul Graham; Ken Grant; Joy Gregory; Sunil Gupta; John Harris; Lyle Ashton Harris; David Hoffman; Brian Homer; Colin Jones; Mumtaz Karimjee; Roshini Kempadoo; Peter Kennard; Chris Killip; Karen Knorr; Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen; Grace Lau; Dave Lewis; Marketa Luskacova; David Mansell; Jenny Matthews; Don Mccullin; Roy Mehta; Peter Mitchell; Dennis Morris; Maggie Murray; Tish Murtha; Joanne O’Brien; Zak Ove; Martin Parr; Ingrid Pollard; Brenda Prince; Samena Rana; John Reardon; Paul Reas; Olivier Richan; Suzanne Roden; Franklyn Rodgers; Paul Seawright; Syd Shelton; Jem Southam; Jo Spence; John Sturrock; Maud Suiter; Homer Sykes; Mitra Tabrizian; Wolfgang Tillmans; Paul Trevor; Maxine Walker; Albert Watson; Tom Wood; Ajamu X

The 80’s: Photographing Britain

Tate Britain, London

- 21 November 2024 – 5 May 2025

- Millbank London SW1P 4RG

- Open daily 10am-6pm

- Prices £20, £5 16-25 Tate Collective

- The 80s | Tate Britain

Further reading:

- New 70:15:40 exhibition addresses underrepresentation in photo industry

- Tate reveals 2025 exhibition lineup: includes huge Lee Miller retrospective

- Capturing the Moment Tate exhibition review – a big flop?

- See the amazing International Landscape Photographer of the Year winners!

- Diverse, unique, resilient: Portrait of Britain Vol.7 shortlist revealed!