Amateur Photographer verdict

The D-Lux 8 is a joy to use thanks to its traditional control dials, with the multi aspect ratio sensor further encouraging creativity. But its JPEGs can be dull, so you’ll get best results from raw.- Engaging manual controls

- Large aperture zoom lens

- Unique multi-aspect ratio sensor

- Much improved viewfinder over D-Lux 7

- User-friendly DNG-format raw recording

- Fixed, rather than tilting rear screen

- Uninspiring JPEG colour

- Minimal handgrip

The Leica D-Lux 8 is an advanced zoom compact camera that’s designed for enthusiast photographers. It’s a development of the Leica D-Lux 7 from 2018, which itself was a re-styled version of the Panasonic Lumix LX100 II. The D-Lux 8 has the same lens, sensor, and core specifications as its predecessor, but it gains a radically reworked control layout based on the Leica Q3, along with a much better viewfinder. All the ingredients are in place for it to be one of the best compact cameras around.

Leica D-Lux 8 at a glance:

- $1595 / £1450

- 24-75mm equivalent f/1.7-2.8 lens with OIS

- 17MP Four Thirds multi aspect-ratio sensor

- ISO 100-25,000

- Up to 11fps shooting

- 2.36m-dot, 0.74x OLED viewfinder

- 3in, 1.84m-dot LCD touchscreen 4K 30p video recording

It’s no secret that the ever-increasing quality of smartphone cameras has decimated the market for traditional compact cameras. But there’s one standout exception at the top of the market, in the shape of Fujifilm’s classically-styled and wildly popular Fujifilm X100VI. With the D-Lux 8, Leica is clearly hoping to grab a piece of the action with a camera that shares many of the same attractions, but which has a zoom lens.

Like the X100VI, the D-Lux 8 has traditional photographer-friendly controls for the main exposure settings, plus a corner-mounted viewfinder in a flat-bodied ‘rangefinder-style’ design. But in contrast, it employs a smaller Four Thirds type sensor with a clever multi-aspect ratio design, joined by a 24-75mm equivalent zoom with a bright f/1.7-2.8 aperture. It’s in much the same price bracket as the X100VI, at $1595 / £1450 vs $1599 / £1600. There’s clearly a great deal to like here, but how does it compete against its popular rival?

How I tested the Leica D-Lux 8

I had the Leica D-Lux 8 on a two-week loan courtesy of Leica UK. During that time, I carried it with me whenever I left the house, including on a couple of photo walks around London and the Kent countryside. I used it across a range of subjects and lighting conditions and tested all aspects of its performance with real-world subjects. This included such factors as autofocus, metering, white balance, image stabilisation, plus of course lens and sensor quality.

I also tested its continuous shooting speed and file-write times against a stopwatch and took a series of images of our standard test scene at each ISO setting. My overall rating is based on a rounded assessment of the camera’s portability and usability, as well its performance and image quality.

Leica D-Lux 8: Features

In terms of specifications and features, the D-Lux 8 is pretty much identical to the D-Lux 7, and therefore the Lumix LX100 II. As before, it’s built around a 20MP Four Thirds sensor, but employs it in a unique way. It never uses the entire sensor area to create images, but instead crops in to offer a range of aspect ratios with the same diagonal angle of view. You can see how this works in the gallery below.

The largest output size is in the 4:3 ratio, at 4736 x 3552px or 17MP. This corresponds to an image area of 15.8 x 11.9mm, which is about half the size of the 40MP APS-C sensor in the Fujifilm X100VI. Then the 3:2 and 16:9 modes get progressively wider but lower, at 4928 x 3288px (16.2MP) and 5192 x 2904 (15.1MP) respectively.

There’s also a square-format mode, which is simply a 12.6MP crop from 4:3. These resolutions may sound low by current standards, but they’re still plenty good enough to make detailed prints on A3 paper.

As previously mentioned, the 10.9-34mm f/1.7-2.8 Leica DC Vario Summilux Asph lens gives a 24-75mm equivalent angle of view. That large aperture, coupled with the relatively large sensor, provides greater potential for blurred backgrounds and shallow depth-of-field effects compared to other compact cameras with similar zoom ranges. Optical stabilisation is built in, and the lens has a thread for 43mm filters.

Leica specifies the sensor’s sensitivity range as ISO 100-25,000, although in use it quickly becomes apparent that ISO 100 is a ‘pulled’ setting that clips highlights a stop earlier. Raw files are recorded in the user-friendly DNG format, which means they should be recognised by most processing software. Naturally the camera can also output JPEGs, but there’s no support for the more recent HEIF format.

Continuous shooting is available at 11 frames per second, but this comes with focus fixed and in 10-bit raw, which limits post-processing flexibility. Drop the speed to 7fps, and you get live view between frames. At 2fps, the camera offers continuous autofocus and 12-bit raw output.

While the shutter speed dial is marked from 1 second to 1/2000sec, the mechanical shutter actually provides speeds from 60 seconds to 1/4000sec. These are selected using an electronic dial or the touchscreen, depending on how the camera is set up. Engaging the electronic shutter extends this to 1/16,000sec, which allows shooting at large apertures in bright light without the help of a neutral density filter.

Video recording is one area where the camera distinctly shows its age. You can shoot in 4K resolution at 30fps, or Full HD at 60fps. However, unlike most recent models, clips are limited to 29 minutes in length.

There’s a built-in stereo microphone, but no option to attach an external mic or monitor your audio using headphones. The HDMI port is only for playback, too – you can’t output to an external monitor/recorder or streaming device.

Bluetooth and Wi-Fi are both built-in for smartphone connectivity via the Leica Fotos app. As usual, you can operate the camera remotely from your phone, and copy files across from the camera for sharing on social media. Unlike with the Leica Q3 and Leica SL3 cameras, though, you can’t use the app to download and install “Leica Looks” for more creative in-camera colour processing.

Leica D-Lux 8 key features

Leica’s D-Lux 8 builds on the six-year-old D-Lux 7, but now with a control layout borrowed from the Q3.

- Flash: Leica supplies a small flash unit that slides onto the hot shoe, with power drawn from the camera. You can also use Olympus/Panasonic dedicated external flash units.

- Lens filters: The lens is threaded to accept 43mm filters and the camera is supplied with a 43mm clip-on lens cap.

- Shutter button: While the shutter release has a retro-style screw-thread, this is purely for a cosmetic add-on button. Screw-in cable releases don’t work.

- Connectors: On the side of the handgrip, there’s a USB-C port for battery charging and transferring files to a computer, plus micro-HDMI for video playback on a TV.

- Power: The Leica BP-DC15 battery is identical to the Panasonic DMW-BLG10E, which means that reputable third-party spares are widely available.

- Accessories: Leica offers a variety of matched cases, straps, and shutter buttons, plus a screw-on handgrip. But all of them are wildly expensive.

Leica D-Lux 8: Build and Handling

While the D-Lux 8 may share its lens and sensor with the D-Lux 7, it’s very different in terms of design. In particular, the control layout has been dramatically simplified to match the Leica Q3 premium full-frame compact. The body shape also echoes the Q3, with a flat front and curved ends which are ultimately inspired by Leica’s iconic M-series rangefinders. It’s worth noting the camera isn’t described as weatherproof, but I used in a couple of light showers without any problem.

Thanks to its reworked body and larger viewfinder, the D-Lux 8 is fractionally larger than its predecessor, at 120 x 69 x 62mm and 397g. It would be a stretch to describe it as pocketable, but it’ll slip easily into a small bag. It’s noticeably smaller than the Fujifilm X100VI, which measures 128 x 75 x 55mm and 521g, but larger than compact cameras with 1-in type sensors and comparable zooms, such as the Canon G7 X Mark II / III, or the Sony RX100 V.

With no semblance of a hand grip on the body, I found the D-Lux 8 somewhat uncomfortable and insecure to carry one-handed. There is, at least, a small thumb grip on the back, but I’d certainly recommend using a wrist strap at least.

Leica offers an accessory grip that screws onto the bottom of the camera and provides something to wrap your fingers around, but of course it’s eye-wateringly expensive, at £105. When you’re shooting, naturally you’ll be supporting the lens and operating its controls with your left hand.

With its plethora of direct controls and simplified interface, the D-Lux 8 is, mostly, a joy to shoot with. It’s a camera where you feel that you’re in control of what it’s doing, rather than at the mercy of its automated systems. The zoom lever provides precise control over composition, which isn’t always the case with compact cameras, and it’s easy to change the main exposure settings with the camera up to your eye.

Lens controls are essentially the same as before. You get a traditional aperture ring, which clicks in one-third stop steps from f/1.7 to f/16. Of course, if you set the ring to f/1.7 and zoom in, you’re still limited by the lens’s maximum aperture: f/2 at 28mm, f/2.3 at 35mm, and f/2.7 at 50mm. There’s also a dedicated manual focus ring, plus switches for focus mode (auto, macro, and manual) and aspect ratio.

As for the top-plate controls, there’s still a shutter speed dial, plus a conventional zoom lever around the shutter button. But otherwise, it’s a case of all change. Where the D-Lux 7 had a dedicated exposure compensation dial, there’s now an electronic dial with a button in its centre, just like the Q3. I set the dial up to adjust exposure compensation and the button for ISO, which gave me direct control of all the key exposure settings.

Rear controls have been dramatically simplified too, to just a d-pad and four buttons. The directional keys are used to position the focus area, while the button in their middle cycles through display modes that show different levels of exposure information. Frustratingly, though, it can only be used to reset the focus area in the face detection and tracking modes. In other AF area modes, there’s no way of quickly re-centering the focus point. This is something Leica really needs to fix with a firmware update.

Above the d-pad you’ll find the Play button, with the Menu button below. As is Leica’s way, pressing this first brings up an on-screen control panel, with repeated presses then cycling through menu pages. The available options are strikingly pared back, with anything superfluous removed. Some people might find it over-simplified, but I think Leica has done a commendable job of keeping the camera easy to use without losing any truly essential settings.

There are two unmarked buttons within easy reach of your right thumb, with the left-hand one slightly raised to make it distinguishable by touch. Out of the box, the left button selects between using the viewfinder and LCD or auto-switching between the two, while the right button toggles between photo and video modes. However, you can easily re-assign either by holding it down; I set the left button to select between Film Styles.

Leica D-Lux 8: Viewfinder and screen

One of the D-Lux 8’s most welcome updates lies with its viewfinder, which is a 2.36m-dot OLED unit with 0.74x magnification and a 4:3 aspect ratio. It doesn’t suffer from the unpleasant colour ‘tearing’ effects that could be visible with the D-Lux 7’s field-sequential LCD, while also providing a larger view, particularly in the 4:3 and 3:2 aspect ratios. The viewfinder isn’t particularly bright, though, which can make it difficult to see clearly on sunny days. This can also sometimes tempt you to apply unnecessary exposure compensation.

The 3in rear screen is also higher in resolution than before, at 1.84m-dots compared to 1.24m-dots on the D-Lux 7. But unfortunately it’s still of the fixed, rather than tilting type. While this helps keep the camera body relatively slim, it now feels out-of-date. I really missed the ability to tilt the screen up for unobtrusive waist-level shooting.

Leica previews colour and exposure live, while stopping the lens down to the taking aperture when the shutter button is half-pressed, which visualises depth-of-field. This all provides a good idea of how your images are going to turn out. Various useful exposure and compositional aids are available, including a highlight clipping warning, live histogram, gridlines and level displays.

One minor quirk is that Leica overlays the main exposure information on a semi-transparent grey strip across the bottom of the screen, which seems sensible enough. But the problem is that it can make you disregard anything at the bottom of the frame, so that unwanted objects creep into your compositions. I wish Leica provided the option to hide this information when you half-press the shutter button.

There is a display mode that provides a completely clean preview image. But then you can’t see what’s going on in the viewfinder when you change your exposure settings, which makes no sense. Oddly those settings reappear when you half-press the shutter button, which to me is the wrong way around.

Leica D-Lux 8: Autofocus

When it comes to autofocus, on paper the D-Lux 8 looks rather dated. It doesn’t employ phase detection at all, instead relying on contrast detection and doubtless depth-from-defocus (DFD) technology. Unlike most cameras of the past few years, you don’t get AI-based subject detection, either; just face/eye detection for people and a basic tracking mode for anything that moves.

Click on any sample image to see the full resolution version

Whether this is likely to matter to you depends on what you intend to shoot. With static subjects the autofocus works just fine, focusing quickly, silently and accurately. I also found the continuous AF and tracking worked perfectly well with subjects that move predictably, for example trains. But with those that move quickly and erratically such as pets or small children, it may well struggle to keep up.

However, at this point it’s also worth pointing out that phase detection and subject recognition aren’t in themselves a panacea. While the Fujifilm X100VI does include both for autofocus, its lens design means it’s not great for tracking moving subjects, either.

Leica D-Lux 8: Performance

In use, the Leica D-Lux 8 is a snappy and responsive performer that rarely gets in the way of you shooting. Flick the power switch, and it takes about a second for the lens to extend and get itself ready. Once it’s awake, though, the camera responds instantly to both the physical controls and the touchscreen. It can take a surprisingly long time to for the lens to retract again when you switch it off, but you’re probably not in a hurry at this point anyway.

The camera is unobtrusive, too, operating almost completely silently if you turn off its various operational beeps (or “acoustic signals”, as Leica calls them). This is always welcome in situations where you’d rather go unnoticed, such as street photography. However, it’s no longer such a huge advantage for compact cameras as it once was, given that most mirrorless models are now extremely quiet too.

I’ve found the battery life to be perfectly respectable. Leica doesn’t supply a CIPA-standard rating, but it seems reasonable to assume it should be close to the 340 shots per charge provided by the LX100 II. In practice, I managed to shoot a couple of hundred frames in a session without exhausting the battery. As reputable third-party batteries are readily available and the camera can be topped up on-the-go using a powerbank, I don’t think there’s anything to worry about here.

One area where the D-Lux 8 doesn’t perform quite so brilliantly comes with continuous shooting. It’s perfectly capable of running at 11fps for a 13-frame burst, but then it takes a while to record the files to card, and during this time it’ll only shoot sporadically. What’s more, if you want continuous AF, it can only shoot at a pedestrian 2fps.

There’s no apparent write speed advantage to using faster UHS-II SD cards, either. In my tests, both UHS-I and UHS-II cards took about 25 seconds to completely clear the buffer. So this won’t be the best camera for fast action. But then again, if that’s what you’re shooting, it makes little sense to choose a camera with a fixed 24-75mm zoom in the first place.

Metering is pretty reliable, although it does have a certain tendency to err on the side of underexposure. This has the advantage that you don’t often end up with clipped highlights, but the flip-side is that files can look a little dull out-of-camera. I often preferred to brighten my images by a third of a stop or more.

Auto white balance leans very much towards neutral results, and unlike many current cameras, there’s no option to bias it towards warmer, more atmospheric output. Leica’s default Standard Film Style is also clearly tailored towards colourimetric accuracy rather than giving punchy colours. While this can be good for portraits, for scenic shots I generally preferred the Vivid setting, although it can be a bit over the top. If you like shooting in black & white, the Monochrome High Contrast option gives fine results.

If you really want to get the most from the D-Lux 8, though, I think it’s best to shoot in raw. Here you should find that the camera’s DNG files are recognised by most imaging software. However, you might have to put in a little more work than usual to get the best out of them. I routinely boosted the colour, contrast, and clarity to a higher degree than I would with most cameras in Adobe Camera Raw. But if you’re prepared to put the effort in, you can get perfectly pleasing results.

At this point, I’m obliged to point out that the D-Lux 8’s Four Thirds sensor can’t match the latest APS-C or full-frame cameras in terms of raw image quality. Especially as it still seems to be the same 2018 design as in the LX100 II; it’s a shame Leica couldn’t have used the newer 25MP Four Thirds sensor that Panasonic has employed in the Lumix G9II and GH7. This means raw files show higher image noise when compared ISO-for-ISO, along with lower dynamic range.

However, it’s important to keep this in context. You still get nice clean images at low ISO, and the large-aperture, optically stabilised zoom means you can often keep the ISO pretty low even when shooting in low light. You can also pull up a couple of stops of additional detail in shadow areas at ISO 200, although there’s nothing beyond that.

Of course, the optical quality of the fixed zoom lens is also crucial. Thankfully, it’s really pretty good, especially considering its large aperture and small size. Sharpness is impressively high across most of the frame, with the best results achieved around f/4 to f/5.6. Unsurprisingly the corners can get a little smeary at wider angles and larger apertures if you examine your files close-up onscreen, but not so much that it’s likely to spoil your images. I’d have no hesitation shooting with the aperture wide open in low light.

Likewise, the optical stabilisation works pretty well for stills, especially if you can find a somewhere to rest your elbows. You can’t expect to get away with the very long hand-held exposures that can be possible with the best in-body stabilisation systems. But it’ll certainly give sharp results two or three stops slower than you’d manage without IS, especially if you’re willing to accept a little pixel-level blurring.

If video is an important part of what you want to do, though, the D-Lux 8 probably isn’t the best choice. While it can deliver nicely detailed 4K footage, again the colour rendition is an concern. The lack of a switchable ND filter also means you’ll need to find a screw-in 43mm filter to get slow enough shutter speeds to render motion smoothly. The in-lens stabilisation isn’t great for video, either, as it can’t for compensate rolling motion around the lens axis, and there’s no electronic correction available to fix this. So hand-held video ends up looking jittery.

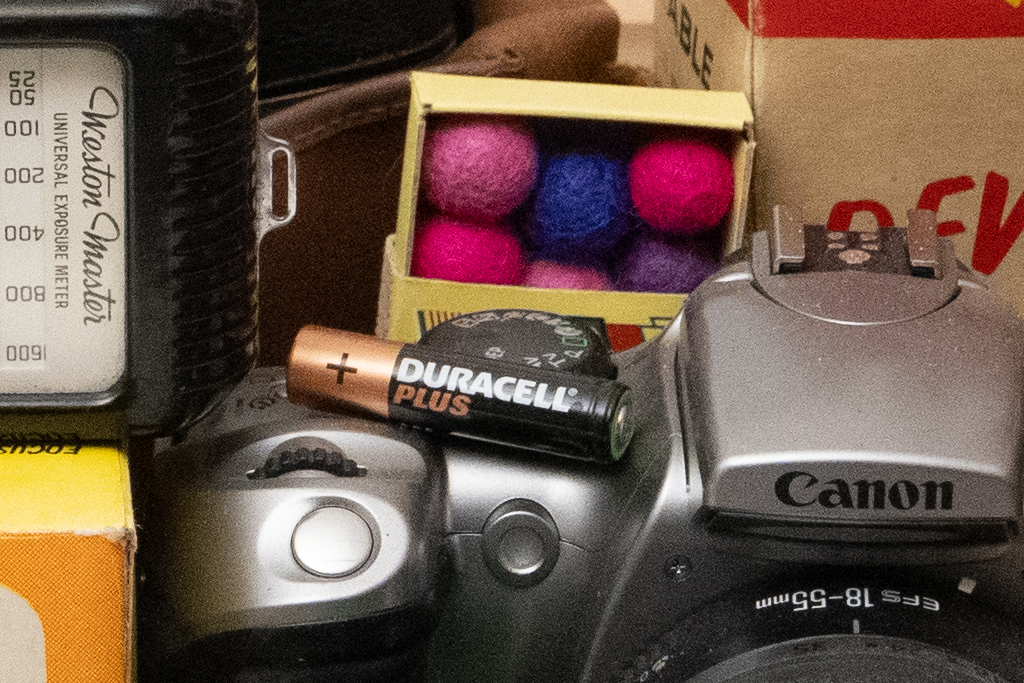

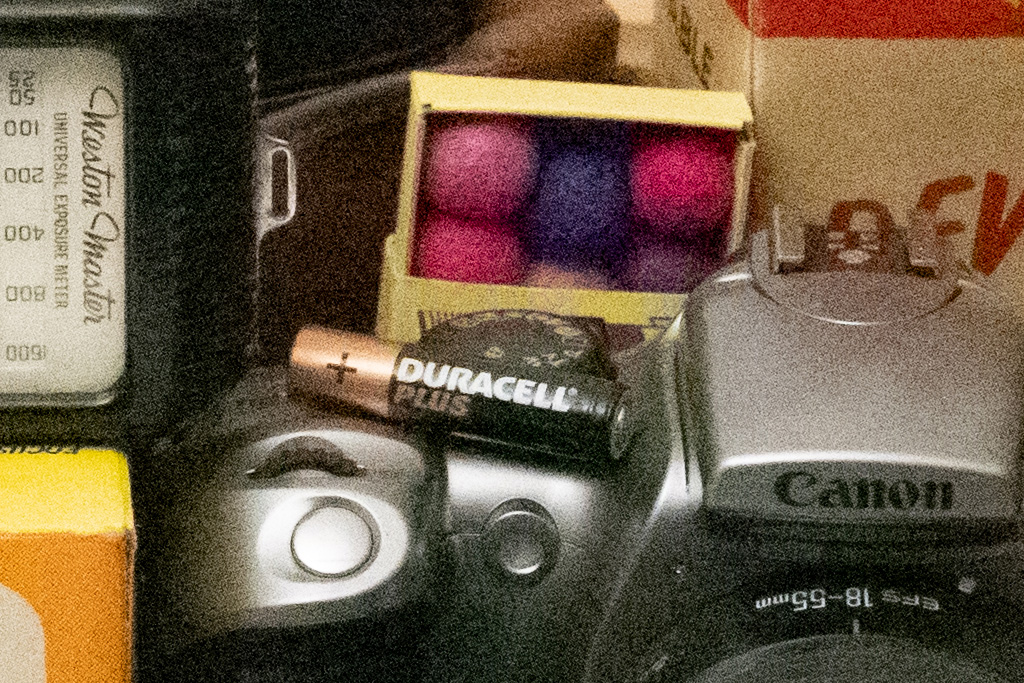

ISO and Noise

At low sensitivity settings, the Leica D-Lux 8 gives nice clean images with decent levels of detail. This is maintained well up to ISO 800, but beyond this, noise has an increasing impact. I’d still be quite happy shooting at ISO 1600, but at ISO 3200 fine detail and colour saturation are suffering noticeably. I’d probably consider ISO 6400 my cut-off point for normal use, although ISO 12500 might be usable with a healthy dose of AI noise reduction. The top ISO 25,000 setting should certainly be avoided.

Below are 100% crops from our standard test scene, shot in DNG raw then processed using Adobe Camera Raw at default settings. Click on any one to see the full image.

Leica D-Lux 8: Our Verdict

It’s great to see Leica trying to revive the enthusiast zoom compact camera with the D-Lux 8. Remarkably, it’s the first new camera of this type since mid-2019. The success of Fujifilm’s X100 series suggests there must be an appetite for such a thing, but the question is whether Leica can persuade photographers to part with their money for what is, essentially, a 2018 model with a facelift.

There’s still plenty to like about the D-Lux 8, though. Panasonic’s LX100 series was always a pleasure to shoot with, thanks to all those analogue controls, and Leica’s updated interface only improves that. The zoom lens provides a good level of compositional flexibility, and I really enjoyed the ability to change aspect ratios via a switch on the lens. It’s great to see an improved viewfinder, too, which fixes one of my biggest gripes with the LX100 II/D-Lux 7. I do wish the D-Lux 8 had a tilting screen, but that would have required a much more significant redesign and a larger body.

What you don’t quite get here, though, is the fabulous out-of-camera colour rendition of the Fujifilm X100 series. Instead, the D-Lux 8’s DNG files need that little bit more work to get the most out of the camera. You don’t get the same resolution and dynamic range as from larger and more modern sensors, either, but that doesn’t mean you can’t get some really nice images. To get obviously better image quality with a zoom lens covering a similar range, you’d have to carry around a rather larger camera.

You might well ask why you’d choose to carry such a camera, if you already have a smartphone with a decent camera. Really it’s all about the user experience here – the viewfinder, the physical controls, the ‘real camera’ feel. It’s completely different way of shooting that involves you so much more in the creative process.

Of course, we can’t ignore the price – the Leica D-Lux 8 may be in the same ballpark as the Fujifilm X100VI, but it costs half as much again as the D-Lux 7 did in 2018. However, inflation accounts for at least half the difference, and the body redesign arguably justifies the rest. If you’re willing to buy used, you could pick up a D-Lux 7 or LX100 II for rather less money and get the same features and image quality. Ultimately though, if you’re tempted by the X100VI but can’t live without a zoom, the D-Lux 8 is the closest thing you can buy new right now.

Follow AP on Facebook, X, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.

Leica D-Lux 8: Full Specifications

| Sensor | 17MP Four Thirds CMOS |

| Output size | 5192 x 2904 (16:9); 4928 x 3288 (3:2); 4736 x 3552 (4:3); 3552 x 3552 (1:1) |

| Focal length magnification | 2.2x |

| Lens | 24-75mm equivalent f/1.7-2.8 |

| Shutter speeds | 60 – 1/4000sec (mechanical), 1-1/16000sec (electronic) |

| Sensitivity | ISO 100-25,000 |

| Exposure modes | PASM, Auto, Scene |

| Metering | Spot, centre-weighted, multi |

| Exposure compensation | +/-3 in 0.3EV steps |

| Continuous shooting | Up to 11fps; 2fps with AF |

| Screen | 3in, 1.84m-dot, 3:2, fixed LCD touchscreen |

| Viewfinder | 2.36m-dot, 0.74x, 4:3 OLED EVF |

| AF points | 49 |

| Video | 4K 30p, Full HD 60p |

| External microphone | No |

| Memory card | SD/SDHC/SDXC |

| Power | BP-DC15 Li-ion |

| Dimensions | 120 x 69 x 62mm |

| Weight | 397g inc battery |