In 1996, the Advanced Photo System, generally known as APS, introduced a new type of film for a new kind of camera that combined simplicity of use with revolutionary hi-tech ways of shooting and processing. Kodak, Agfa, FujiFilm and Konica made the film. Kodak, Nikon, Canon, Minolta, Olympus and more came on board with cameras that ranged from simple point-and-shoot compacts to top-notch interchangeable lens single lens reflexes (SLRs). APS must have seemed like a really good idea at the time. Predictions were that it would replace 35mm and change photography for ever. It lasted less than ten years.

How it worked

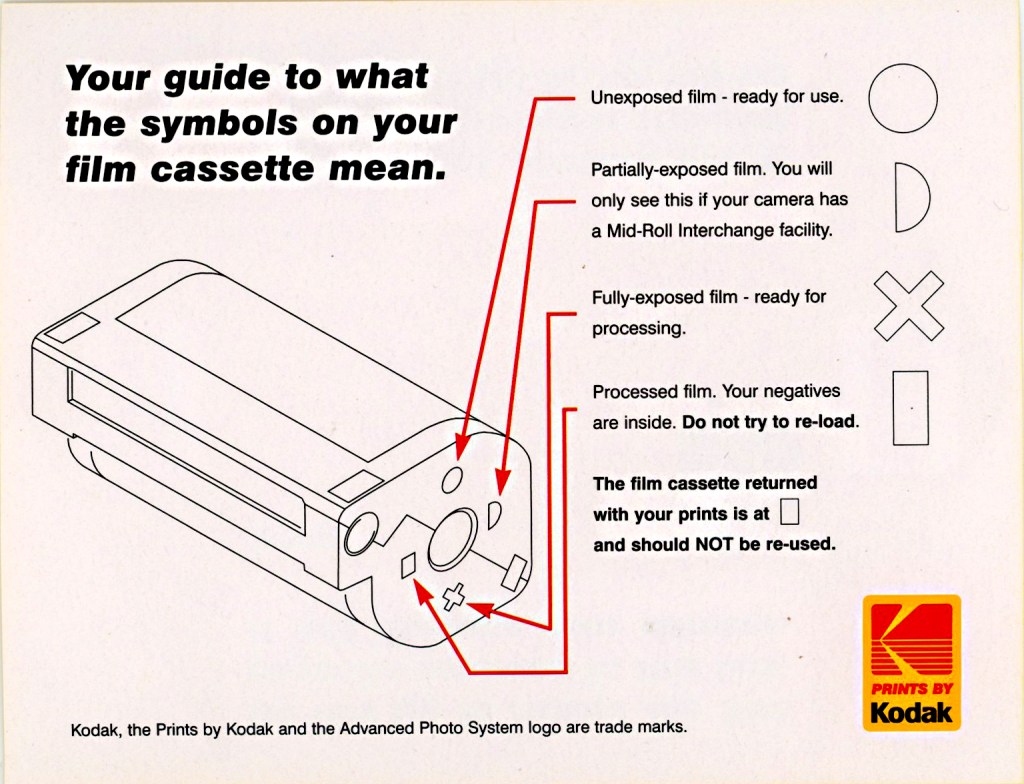

The four APS film makers marketed their products under different names: Kodak Advantix, FujiFilm Nexia, Agfa Futura and Konica Centuria. The film was 24mm wide with two sprocket holes to a frame. Unlike 35mm, sold with a tongue of film protruding from its cassette, APS film was completely enclosed in a special slimline cassette dropped into a chamber in the base, side or top of the camera. Four indicators were shown on the end of each cassette to indicate the state of the film inside. A full circle denoted that the film was unexposed, a half circle denoted partial exposure, a cross denoted the film was fully exposed but not processed, a rectangle denoted that the film had been processed.

The cassette incorporated a light trap which opened only when it was in the camera and the film was being automatically loaded, wound for exposure and rewound. The light trap then closed. On some cameras the film could be removed halfway and re-inserted later. For this, the camera rewound the film, closed the light trap and, when it was re-inserted, the light trap opened and the film was automatically wound to the appropriate position. This was accomplished by the camera’s Information Exchange (IX) system which recorded details of the last frame’s location on a transparent magnetic coating covering the entire film surface.

The IX system also recorded date and time of each exposure, shutter speed and aperture data and the required format of the picture. Cameras gave a choice of three formats using a control marked ‘H’, ‘C’ and ‘P’. The initials stood for ‘High Definition’, which used the full APS format of 30.2×16.7mm; ‘Classic’, which cropped the image to 25.1×16.7mm; and ‘Panoramic’, which cropped the image to 30.2×9.5mm. The cropping was produced by the processor at the printing stage from each of the full frames by reading the requirements from the magnetic strip. The photographer received everything back in a box containing the film wound back and sealed in its cassette, prints in their requested formats, a reference sheet showing all the pictures in miniature and how they had been cropped and an envelope for returning the film to order reprints or enlargements.

All of this was available on the best, and the most expensive, cameras. More basic models substituted the magnetic coating for a simpler Optical IX system that used a light source to expose data onto parts of the film outside the image area. Mostly this was confined to information about format selection. Image format choice, drop-in film load, autofocus, auto film wind and simple-to-sophisticated forms of auto exposure were standard on most APS cameras, which usually ran on CR2 batteries singly or in pairs, or CR123A cells.

Today, APS cameras – some in unusual designs, many attractively colourful, most unexpectedly cheap – are beginning to be collectable. And, with a little perseverance, they are still usable.

Single lens reflexes

Canon, Nikon and Minolta led the way in APS SLRs, all offering the versatility of reflex viewing and interchangeable lenses.

1996: Canon EOS IX

Considered one of the best APS SLRs, the EOS IX is a very stylish camera with a steel alloy finish to a futuristic looking body shaped like a circle around the lens. Pressing a button on the back changes the formats, which are indicated by masks in the viewfinder. The 24-85mm f/3.5-4.5 standard lens matches the body colour although Canon’s range of black EOS lenses, made for the company’s 35mm SLRs, can also be used. Shutter speeds run 30-1/4,000sec with flash sync at 1/200sec, using the camera’s in-built pop-up flashgun or an external flashgun that fires via a hot shoe.

1999: Nikon Pronea S

This was the company’s second foray into APS SLRs, being a simplified version of the previous, and somewhat larger, Pronea 6i. It’s an extremely compact, silver-finished, plastic-bodied camera that couples all the advantages of 1990s SLR technology with the simplicity of a point and shoot camera. Automatically set shutter seeds run 30-1/2,000sec and a small flashgun pops up from the side of the body, synchronised at 1/125sec. The usual standard lens is a 30-60mm IX Nikkor but the camera works with all the Nikon autofocus lenses as well, although the reverse isn’t true – IX lenses made for the Pronea are not compatible with Nikon’s 35mm cameras. Using Nikon’s older manual focus lenses, with the camera set to shutter priority to adjust speeds while selecting apertures on the lens, gives full manual control.

1996: Minolta Vectis S-1

Whereas Canon and Nikon used lens mounts compatible with their 35mm camera lenses, Minolta designed its V-lens specifically for its APS cameras, and then briefly for a DSLR called the Dimage RD3000. This restricts the number of lenses available but has the distinction of including a 400mm autofocus mirror lens, the only one of its kind made for the APS format. The camera also lacks the traditional SLR pentaprism, substituting a system of mirrors which places the viewfinder eyepiece at the end of the body, resulting in a smoothly contoured, compact design. The spec also offers 14 segment average metering with optional spot metering, auto and manual exposure, a shutter speeded 30-1/2,000sec and a pop-up flashgun.

Bridge cameras

Like 35mm cameras before and digital models that followed, the APS format had its share of bridge cameras to provide reflex viewfinding in fixed lens, fully-auto bodies.

1996: Olympus Centurion

Similar in style to the Olympus iS series of 35mm bridge cameras but about half the size, the Centurion sports a 25-100mm f/4.5-5.6 lens zoomed by a toggle switch on the back with a pop-up flash on top of the viewfinder prism. Exposure is programmed but can be fine-tuned by a dial with subject options selected by pressing one of four segments around its edges for landscapes, portraits, sports and night subjects, illustrated on an LCD screen. A button in the centre reverts the system to fully automatic.

1996: FujiFilm Fotonex 4000ix SL

The Fotonex is similar in design to the Olympus but slightly larger and more rounded, with similar controls in different places. The 25-100mm f/4.5-5.6 lens is zoomed by a toggle around an exposure mode button. Press the button and the camera gives programmed automation, but this can be fine-tuned by a button beside the LCD screen which is depressed sequentially to select each of the usual four exposure modes.

Compact cameras

Compact cameras for the APS system were made in abundance by all the major manufacturers. They were mostly epitomised by small palm-sized bodies, not much larger than film disposable cameras. Auto exposure and focus were the norm, and some boasted the simplest of manual controls. The Kodak Advantix F350, for example, had a fixed focus, fixed aperture lens that emerged from behind a cover as a lever on the base was pushed, activating a tiny pop-up flash at the same time. Auto exposure was controlled only by the shutter speeds.

Unsurprisingly, Kodak Advantix cameras, in various forms and specifications, dominated the market, but APS models also appeared from unexpected manufacturers. The Rollei Nano, for example, was very stylish, as were the Contax TiX, Nikon Nuvis V and Leica C11. Many APS compact cameras were very similar in their designs and modes of operation. But there were a few that defied convention and took a different look, not just at APS, but at camera design in general.

1996-2001: Canon IXUS cameras

Canon’s first APS camera in 1996 was the IXUS IX 240, also known as the Elph. Stylishly made of stainless steel it features a 2x zoom lens in an ultra-compact design, about the size of a credit card with the thickness of a cigarette packet. In 1996 it was the world’s smallest autofocus zoom compact.

The Canon IXUS Z90, also from 1996, is larger than usual, about the size of a 35mm film compact. Its unusual feature is a large saucer-shaped flap across the front. Pressing a switch on top of the body releases the flap to swing open, revealing two flashguns on its inner surface, one to shoot the picture and a smaller pre-flash to reduce red-eye. The 22.5-90mm lens automatically extends on telescopic tubes as the flap opens.

In 1999 the IXUS X-1 was designed for rugged outdoor use. With a stylish semi-circular body, the camera is waterproof to a depth of 5m and guaranteed to float even with a film and battery on board. Extra-large controls are provided for easy use when wearing gloves, and the large viewfinder can be used while wearing ski goggles or mask.

The strangest of the range came in 2001 with the IXUS Concept Arancia made in the size, shape and colour of an orange with silver-like appendages. It was produced in a limited run of 20,000 cameras.

1998: FujiFilm Fotonex 3500ix

When not in use, the 21-58mm zoom lens of this small metal camera is covered by a removable plate. Take it off, reverse it and attach it to the back of the body and it turns on the power while revealing the camera’s controls and exposure modes displayed on an LCD screen. It is also possible to select one of ten captions – ‘Vacation’, ‘Wedding’, ‘Party’, ‘I love you’, ‘Thank you’, ‘Happy birthday’, ‘Merry Christmas’, ‘Festival’, ‘Trip’ or ‘Memories’ – which will then be printed on the back of the chosen picture. But the Fotonex’s unique selling point is the way the plate can be entirely removed from the camera, then by means of an infrared system, to remotely set controls and fire the shutter from a distance.

1998: Nikon Nuvis S

This is an extremely robust little camera in which everything except the small flashgun is hidden when the case is closed. Pulling the two halves of the case apart, a bit like a very big Minox, reveals the automatically extending 22.5-66mm macro lens and shutter button. On the back, there is a toggle to zoom the lens and a small LCD screen to indicate functions that include date and time display, low battery power warning, flash mode, frame counter and red eye reduction indicator. Multiple flash modes and shutter speeds of 2-1/400sec complete the spec.

1999: Olympus iZoom 75

If you are familiar with the Olympus Mju 35mm cameras, the design of this one will be familiar with its sliding flap that doubles as an on/off switch while moving aside to allow the lens to extend. Exposure is programmed, focus is automatic, a tiny LCD screen on the back displays functions and, along with black, it’s also available in a stylish slivery-gold body.

2000: Kodak Advantix Preview

If ever a film camera pre-dated the digital era, this is it. From the front, it’s a typical Kodak APS model with a flip-up cover containing a small flashgun to protect the pop-out 25-65mm zoom lens. But turn the camera round, and on the back there is an LCD screen. As the shutter is fired, the picture is taken and recorded on film in the normal way. But then, pressing the ’Preview’ button the LCD screen, displays the scene just taken in full colour, offering the choice of whether or not to print that frame. If the photographer decides against it, another shot can be taken and previewed… and so on until the result is acceptable.

Of course, it would have been better if the scene could have been previewed before it was committed to film. But the way the camera was designed encouraged more film to be shot than might otherwise have been used – something that no doubt pleased Kodak no end.

2001: FujiFilm Nexia Q1

APS cameras don’t come much more simple than this. Confusingly, some Q1s shoot only in the full-frame ‘H’ format, others offer a choice of ‘H’ or ‘C’. The shutter is fixed at 1/100sec and the lens focal length is a slightly wide 22mm. There’s a built-in flash with red-eye reduction and that’s about it. For the user, it’s a bit basic, but it will appeal to the collector for being available in four colours: silver, blue, purple and orange.

Using APS today

At the time of writing, a check on eBay revealed more than 7,000 APS cameras for sale, so there’s no problem in buying one second-hand. APS film was discontinued in 2011, which means what’s available now will be expired. But you can find plenty of such film, still usable, on eBay and sometimes also at Analogue Wonderland. DS Colour Labs in Stockport is one of the few still offering processing for APS. The alternative is to do it yourself, when the first problem is getting the film out of the sealed cassette.

At one end of the cassette, adjacent to the lip, there is a tiny socket which opens the light trap. In the centre of the cassette there is another socket and turning this pushes the tip of the film through the open light trap, to be grabbed and completely extracted. A two-ended tool was once sold for this purpose. Today, the only one to be found is in America for $10 – plus $90 to ship it to the UK! However, if you own one of those sets of miniature screwdrivers sold in places like B&Q, all is not lost.

The cassette light trap can be opened by twisting a 2mm flat screwdriver in the light trap socket. Then the film can be ejected by turning a 3.5mm Philips screwdriver in the centre socket. Be aware, though, that the film is so securely attached to the spool inside the cassette that it might not be possible to remove the entire roll. When it comes to a stop, you need to cut it and lose the final few frames. Of course, all this needs to be performed in the dark, so it’s a good idea to practise with an old film in the light first.

APS film is 24mm wide, so it won’t fit the spiral of a 35mm tank. But a quick internet search reveals a company called FilmStuffLab in the States that sells APS spirals on Etsy, made to fit Paterson tanks. Failing that, if you own a universal tank in which the top spiral click-stops into slots for different film sizes, you might be able to engineer an extra slot suitable for the width of APS. Developing, printing or scanning negatives can then be carried out as you would process any 35mm mono or colour film.

Related reading:

- Film stars: Canon’s A-Team of SLRs

- Film stars: Stereo camera photography

- Best 35mm Half-Frame Film Cameras