Stereo pair produced digitally from negatives shot with a Stereo camera (Stereo Realist). Credit: John Wade

We see in three dimensions because each eye takes in a slightly different view from the other. The brain compares the differences and uses the information to create the illusion of depth in the single view we see every time we open our eyes.

Before photography, artists used this theory to draw stereo pairs. So when photography came along, cameras were produced with two lenses that shot two pictures simultaneously. When the resulting images were placed in a viewer, so that the left eye saw only the picture taken with the left lens, and the right eye saw the one from the right lens, the illusion of three dimensions was recreated.

Stereo photography dates back to the 19th century and the daguerreotype era, when images were made on silver-plated copper. It regained popularity in the 1900s using glass plates, died away, then made a comeback in the 1950s and early 1960s, with cameras made for 35mm, 120mm and 127mm rollfilm, and even 16mm subminiature film. These are the cameras that you can still find second-hand for use today.

Gaumont Stereo-Spido (left) and Unis Monobloc (right). Credit: John Wade

Using a stereo camera

Stereo pictures should be shot to include strong foreground subjects, with interesting detail in the middle distance and an attractive background. This requires a good depth of field, working at the lens’ smallest aperture. The best method is to focus the lens at its hyperfocal distance. Do this by setting infinity on the lens’s focusing ring against the aperture you are using on the depth-of-field scale. Then look at the opposite end of the scale to see what distance is set against the same aperture. Everything between those two distances will be in focus.

A good stereo image needs strong foreground interest and a deep depth of field. Credit: John Wade

You’ll need a viewer to see the stereo effect. Many of those made for specific cameras only accepted 35mm slides or transparencies, viewed by direct light, sometimes with the aid of a bulb and battery. Ignore those and go for a viewer that accepts prints. One very simple and inexpensive example was made for the VistaScreen system. These and similar types turn up regularly on eBay, often complete with a set of commercially produced stereo cards.

The cameras

The Stereo Realist, a 1947 camera that’s still usable today. Credit: John Wade

Stereo Realist

- Launched 1947

- Format 35 24x24mm stereo pairs on 35mm film

- Guide price £70-80

The Realist has three lenses: two outer ones to take the pictures and a centre one that reflects its image down to a viewfinder on the base of the body. It is therefore used in a kind of ‘upside down’ way, with an eye to the base-mounted viewfinder and the bulk of the body against the forehead.

A coupled rangefinder window sits beside the viewfinder, and focusing is by a knob at one end of the body. The knob is surrounded by a depth-of-field scale, making it easy to set the hyperfocal distance. As the focusing knob is turned, the lenses remain stationary and the film plane moves backwards and forwards. Apertures of f/3.5-f/22 are set around one lens, linked to similar apertures in the opposite lens. Shutter speeds of 1-1/150sec are set on a ring around the viewfinder lens.

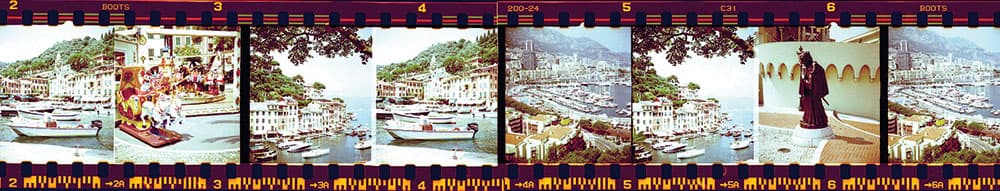

A strip of stereo negatives from the Realist reversed digitally into positives. Credit: John Wade

The shooting-and-winding mechanism is designed so that matching picture pairs appear on film three frames apart. A tiny notch at the film plane, in the bottom of the right image area, registers on the film when it is exposed to indicate right from left images when they are mounted for viewing.

The Wray Stereo Graphic. Credit: John Wade

Wray Stereo Graphic

- Launched 1955

- Format 28 24x24mm stereo pairs on 35mm film

- Guide price £50-70

A fixed shutter speed, with apertures of f/4-f/16 that are designated by weather conditions, make the Stereo Graphic particularly easy to use. The lenses are fixed focus, but one is set at infinity, the other on the middle foreground. This ensures sharp focus from 4ft to infinity in the final stereo image.

The Sputnik for 120 rollfilm. Credit: John Wade

Sputnik

- Launched 1959

- Format Six 5.5×5.5cm stereo pairs on 120 film

- Guide price £80-120

This is a three-lens camera, all three being linked by gears to focus together. The centre lens reflects its image up to a large, bright reflex viewing screen on top of the body. A bar beneath the lenses moves to simultaneously set apertures of f/4.5-f/22 in both lenses. Shutter speeds of 1/15-1/125sec are set on one lens and transferred to a second shutter in the other.

Duplex Super 120. Credit: John Wade

Duplex Super 120

- Launched 1956

- Format 24 24x24cm stereo pairs on 120 film

- Guide price £180-200

The Duplex runs rollfilm vertically, recording stereo pairs side by side across its width. Twin thumbwheels beneath the lenses set apertures of f/3.5-f/22 and shutter speeds of 1/10- 1/200sec. Another thumbwheel above the lenses is turned to focus them. Because the lenses are closer together than on most stereo cameras, the stereo effect is more pronounced when shooting subjects closer to the camera.

Coronet 3-D Camera. Credit: John Wade

Coronet 3-D

- Launched 1953

- Format Four 5×4.2cm stereo pairs on 127 film

- Guide price £20-30

The Coronet features a binocular viewfinder that is used with both eyes. A fixed shutter speed, fixed aperture and fixed-focus lenses make this a basic snapshot stereo camera. When shooting stereo pictures, numbers on the film’s backing paper are wound 1, 3, 5 and 7. Twisting a small knob on the lens panel masks one of the lenses and then, counting the usual 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 numbers on the backing paper allows you to shoot eight single non-stereo pictures.

View-Master Personal Stereo Camera. Credit: John Wade

View-Master Personal Stereo Camera

- Launched 1952

- Format 69 12x13mm stereo pairs on 35mm film

- Guide price £60-80

As 35mm is run through this unusual camera, masks restrict the images to the top half of the film. When the film is at an end, a control is turned on the front of the body. This shifts the lenses from the top of the shutter to the bottom, at the same time reversing the gearing so that turning the film wind knob in the same direction now winds the film back into the cassette, shooting another set of images on the lower part of the film. The resulting stereo pairs can be viewed in a View-Master viewer.

The 16mm Meopta Mikroma subminiature stereo camera. Credit: John Wade

Stereo-Mikroma

- Launched 1961

- Format Varying number of 12x13mm stereo pairs on 16mm film

- Guide price £120-150

Here’s a camera for the more ingenious enthusiast – because it takes 16mm film, still sometimes found on eBay. Preload the film into the camera’s own cassettes, and you have a true subminiature stereo camera with twin Meopta Mirar 25mm f/3.5 lenses and shutter speeds of 1/5–1/100sec. The first model, made in green leather, uses a sliding bar to tension the shutter; the second model, in black or grey leather, automatically tensions the shutter as the film is advanced.

Read our guide to the best 35mm film cameras and types.