When Seamus Murphy began photographing America in 2005, he wasn’t thinking about Russia. He was chasing a long-held idea: a book on post-industrial America to coincide with the 50th anniversary of Jack Kerouac’s 1957 book, On the Road. ‘I sort of missed that by a few years,’ he says with a grin.

Murphy was born in the UK (1959) and grew up in Ireland. Some of his earliest memories are political. In Dublin in 1963, he watched President John F. Kennedy pass by from his father’s shoulders; months later, he remembers his mother weeping at the news of the assassination. At school in 1970, a teacher read aloud from a paperback about Communist Russia and the persecution of religion throughout the Soviet Union.

Dark power

From childhood, Murphy absorbed two contrasting myths: America, a beacon of freedom that welcomed the Irish, and Russia, a dark power intent on taking over the world. He says, ‘America was a dream we had through TV, films and music.’

In 1983 he went to the United States, living there for some time, a period in which he taught himself photography. What followed was a career in photojournalism that took him to Afghanistan, Gaza and Iraq. Eventually, he turned his lens back toward America itself, determined to see how its ideals held up at home, an impulse that became the genesis of Strange Love.

Leafy London

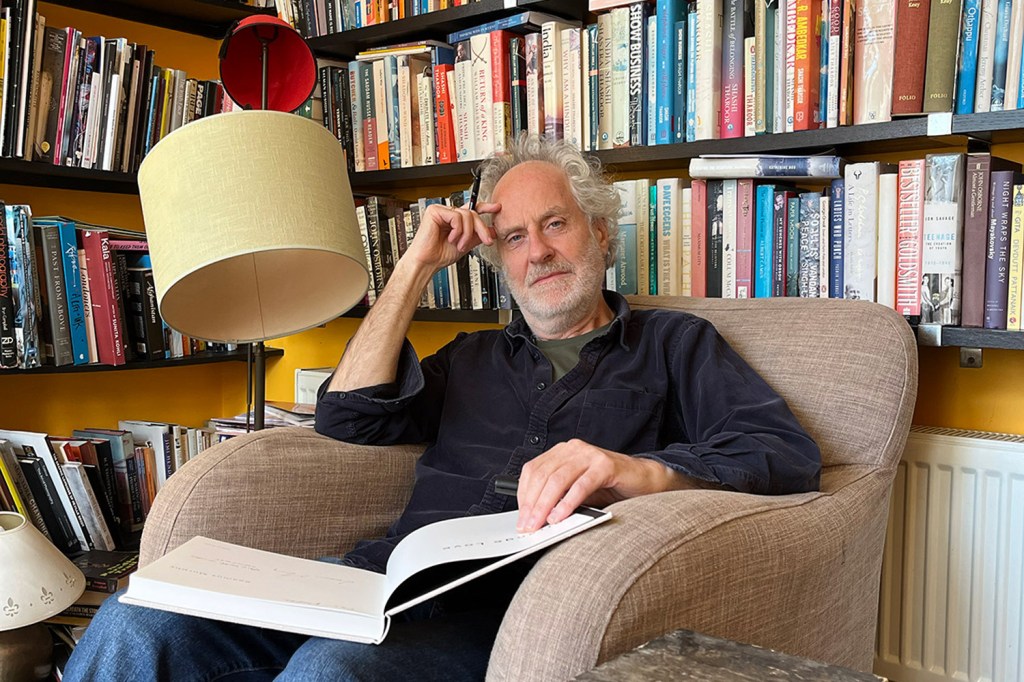

It’s a crisp early autumn morning on Tradescant Road in Vauxhall, South London, named after the 17th-century gardener John Tradescant the Elder, who helped seed the nation’s love of exotic plants. The leaves are beginning to brown; the smell of spices tangles with the British fry-up. Terraced housing squats beneath newly built rotundas, barber and beauty shops promise a hair wax and beard trim. The biggest Rottweiler I’ve ever seen lumbers past, towing a hooded man on a scooter.

From the street, I peer through a window. The silhouette of photographer Seamus Murphy waves back. Inside, Murphy settles into an armchair surrounded by towering shelves of books that tilt and lean like well-thumbed companions. He’s dressed in a dark shirt and jeans, the morning light tracing his wiry silver hair. A copy of Strange Love rests open on his knee as he talks — measured, reflective, occasionally punctuated by a sharp laugh. The room, like his pictures, feels lived-in and layered: thoughtful clutter, quiet intensity. There’s the sense that every object has a story.

Two worlds, one rhythm

As Murphy’s American project drifted and other assignments took over, Russia crept into view. ‘I went to Russia a few times and the idea hit me that there was something there too, he recalls. ‘Then Trump started coming up in 2016 – this is exactly what I was thinking a few years back, the relationship between America and Russia, that strange flirtation. I decided to go back to Russia in a very dedicated way.’

Murphy based himself in the Urals, in the industrial city of Perm. ‘It felt like Pittsburgh,’ he says. ‘Industrial, tough, a big veteran population, immigrants, loyal people. The kind of hinterland that both Putin and Trump could work on.’ There, while the world obsessed over geopolitics, he set about finding lives that quietly mirrored each other on either side of a divide.

Russia or America, guess again

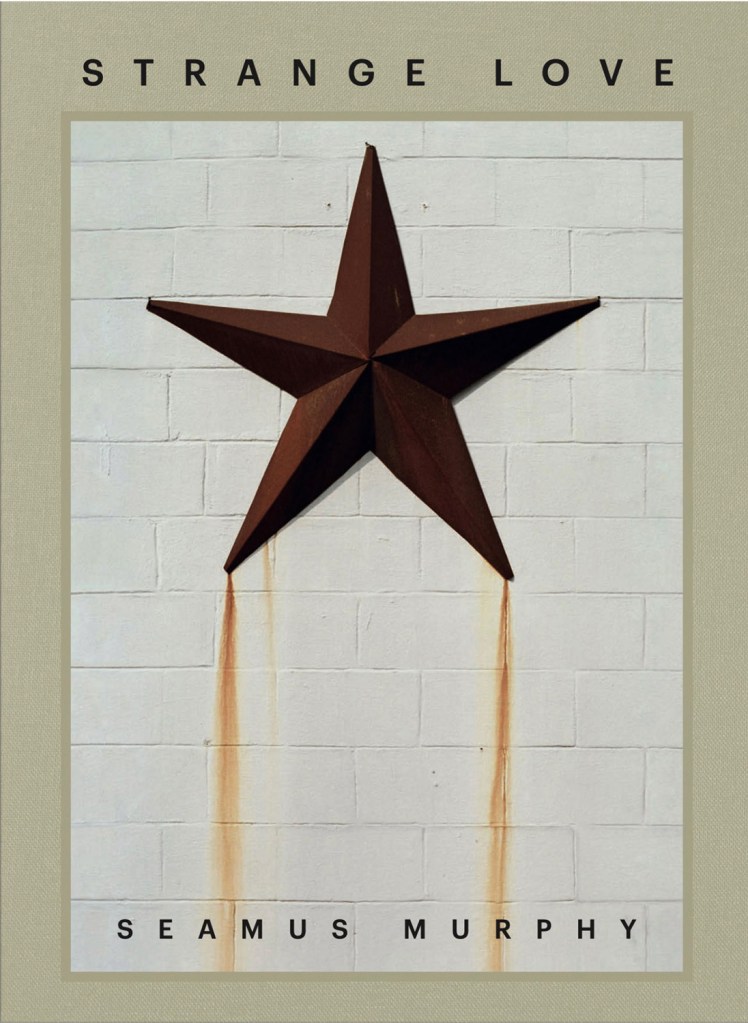

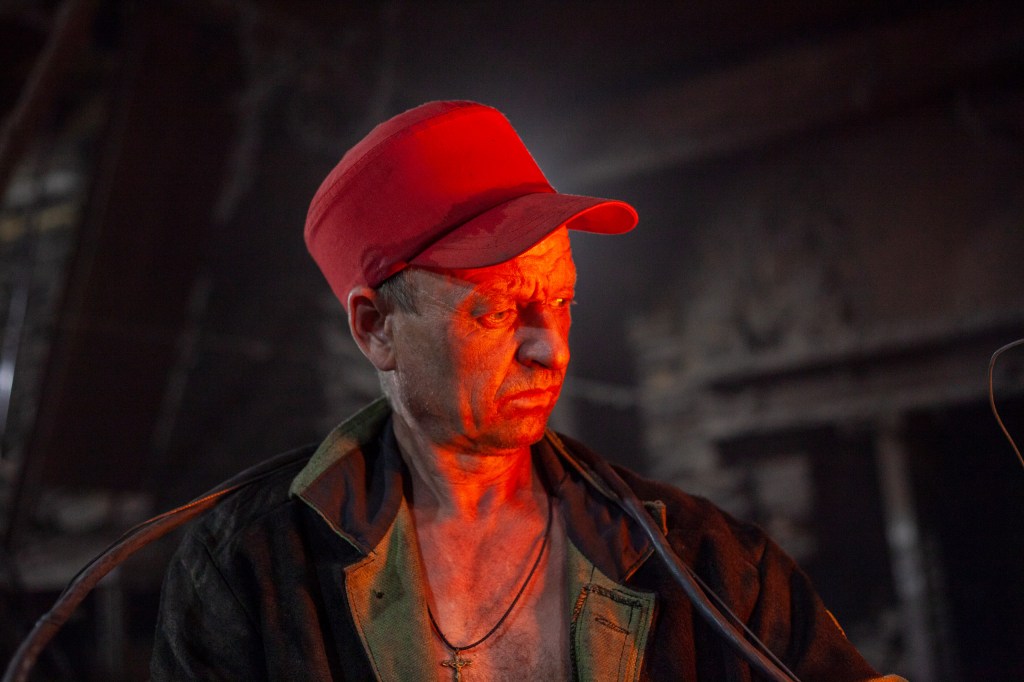

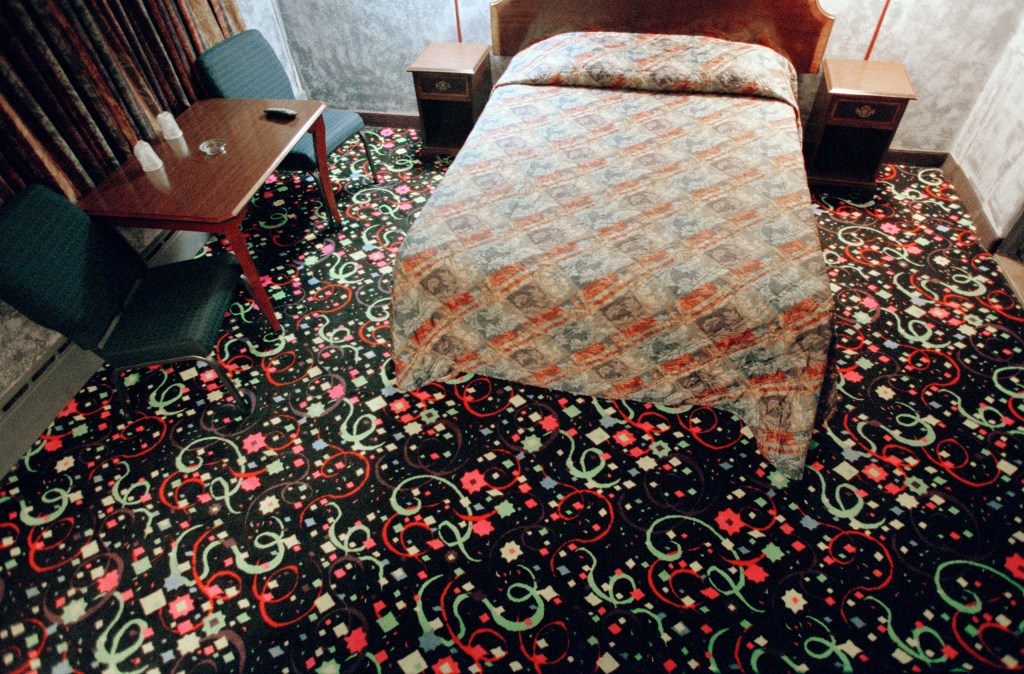

Strange Love, published by Setanta Books, brings together Murphy’s photographs from the United States and Russia between 2005 and 2019. The sequencing is simple but unsettling: U.S., Russia, U.S., Russia. No captions, no dates, no clues. Only the viewer’s own assumptions to trip them up.

‘When you look through the book, you can wonder, which country is this?’ he says. Murphy himself often struggles. ‘Even now, when I pull out six prints, I sometimes have to remind myself which are which.’ The effect is deliberate. ‘It’s about humanism. Who creates these enemies? Who says we have to kill these people because they’re so different? Look through the book and see how many times you get lost between them.’

Murphy’s Russia is not the enemy and his America is not the hero. Through his lens, both become places of ordinary life, of labour, longing and survival. ‘It’s about how similar we are,’ he says. ‘How working people live, love and get by under these huge systems of power. The geopolitics are big, but the lives are small and familiar.’

A question of colour

When he first began the American work, Murphy had been a committed black-and-white photographer. ‘I’d been shooting black and white for many years. I wouldn’t even think about it,’ he says. ‘But America already looks like nostalgia. Everything there looks like a 1950s version of the modern world.’ So he switched to colour. ‘I wanted colour that felt like Eggleston or Hopper, that grainy, cinematic quality. Not too clean. Not too clever. Just something that looked like how it feels to be there.’

In Russia, he found himself shooting the same way. ’It wasn’t about the gloom or the grey. It was about the people. How they behave, how they relate to their surroundings. A good picture is a good picture. You see it in front of you and react.’

The choice of colour and consistency of tone make the disorientation even greater. What looks like an American diner turns out to be a café in Perm; a gas station in Russia resembles something from California’s Googie age.

The art of getting lost

Murphy resisted the temptation to pair pictures literally. ‘So I made it all one image over a two-page spread.’ he says. ‘I wanted the confusion to build slowly. Maybe three pages later, you start thinking, wait, where are we now?’ That’s the whole point of Strange Love.’

He sees the book not as a travelogue or polemic but as an experiment in empathy through misdirection. He adds, ‘The sequencing was deliberate but not obvious. I wanted you to get lost, to feel that visual unease. The lives mirror each other so closely that it’s easy to lose your bearings.’ If you do get lost, you can get back on track by checking the image and locations in the index of thumbnails at the back of the book.

That visual confusion mirrors the political one. The blurred lines between patriotism and propaganda, pride and insecurity. In Murphy’s world, flags, factories and dance halls echo each other across continents.

Making the book

The project took years to reach print, surviving false starts. Of his editing process he says, ‘I scatter small prints across the carpet and move them around. Meaning changes when you see prints, things you thought would be in the book just don’t work. And when you take them out, the sequence gets stronger.’

He eventually whittled thousands of frames down to around 130 images. ‘I sent a PDF to publisher Twin Palms, and that night they emailed: We’re going to publish this. Then the pandemic hit and everything collapsed. Years later, I met Keith Cullen from Setanta books at Photo London, that’s how the book finally happened.’

Helping hands

Murphy is quick to credit his designer, Lizzie Ballantyne, who also worked on The Republic, a book that captures the spirit of Irish life in the centenary of Easter 1916 and The Hollow of the Hand, a collaboration with PJ Harvey’s powerful poetry. ‘You come with ideas and the designer says, “That’s not going to work,” and they show you. It’s a conversation.’

Murphy also acknowledges friend and film director Nicholas Barker, who helped with the sequencing over many years and changes. And most helpful of all in the early America days was photographer Jocelyn Bain Hogg, ‘He has such a great grasp of what photography, and photography books are all about, and what they can be.’

As for the layout, there was debate. ‘The temptation was to play the pictures directly against each other, but I just thought it was too neat,’ says Murphy. ‘It works better when the echo sneaks up on you.’

A European eye on America

Murphy is aware that photographing America as a European comes with baggage. ‘Every photographer wants to cover America, but we’re up against so much history and the weight of everyone who’s already done it. And as a European, you’re always the outsider.’

He laughs at the thought of pitching it to American publishers. ‘People told me, don’t bother. They’re not going to get it. There’s this thing about a European coming in and telling them what’s what, you’ll be up against that. And yes, bringing Russia into it definitely made it more interesting. It stopped being just another European looking at America.’

Tools and temperament

For the technically minded, Murphy’s rule is simple: ‘The film is all America; Russia was digital,’ he explains. ‘But I don’t think that matters. Sometimes you can tell which is which, sometimes you can’t. And that suits the book’s idea perfectly.’

He used Canon digital bodies for Russia, 5Ds and 5D IIs, after years of film Leicas and Canons. ‘It was never about film versus digital,’ he says. ‘It’s about what the picture feels like. If the feeling’s right, the medium doesn’t matter.’

Though Strange Love inevitably brushes against politics, Murphy insists: ‘It’s a humanist project. It’s about ordinary people caught between two systems of power, the ones who always pay the price.’

Truth, fiction, and familiarity

He’s not interested in proving a thesis so much as prompting a question: can we even tell the difference anymore? The answer, looking through Strange Love, is often no. The same cars rust in the same light; the same faces glance up from factory gates and half-lit bars.

When asked what the book means to him, he pauses. ‘The book is done. It’s on the shelf. It’s got its ISBN, that little mark in the world,’ he says. ‘Until you make the book, it’s unresolved. When it’s done, you can finally let go.’

Strange Love is a farewell of sorts – to the long haul of fieldwork, to an old way of seeing the world divided neatly into East and West, to the assumption that human stories must belong to one flag or another. Murphy’s pictures make the case, quietly, beautifully, that they never did.

Strange Love by Seamus Murphy is published by Setanta Books, hardback, £60, 88 Images, 192 pages. ISBN: 9781915652218