The year AP was launched, 1884, a photographer’s life was a lot easier than it had been a few years before. But it was still complicated at a time when camera owners needed to be half artist and half chemist. There was no roll film. Exposures were made on rigid glass plates.

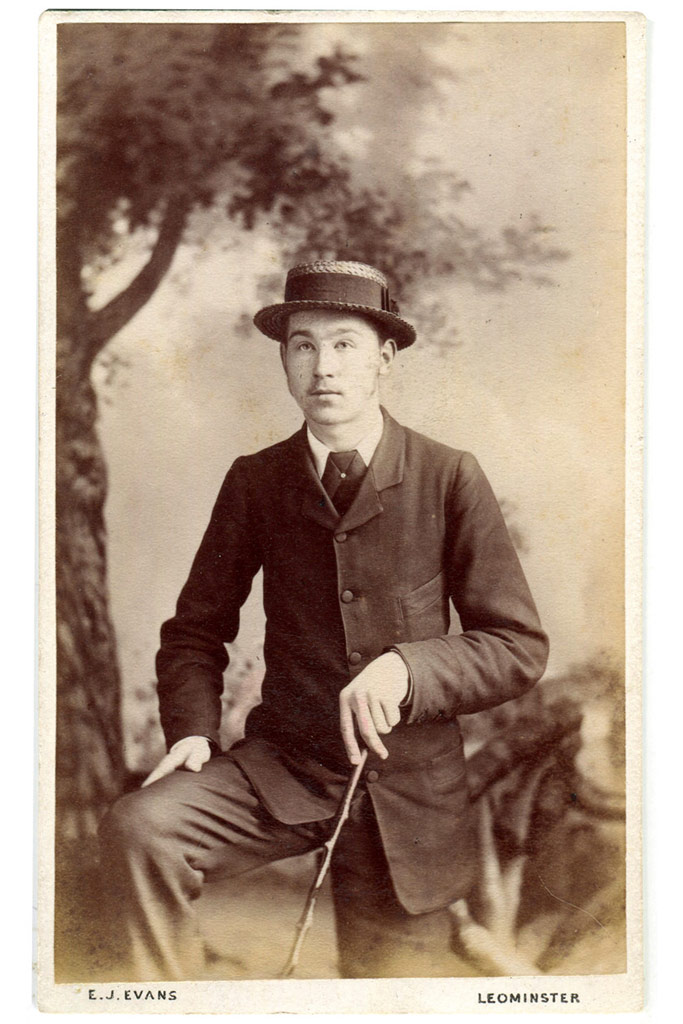

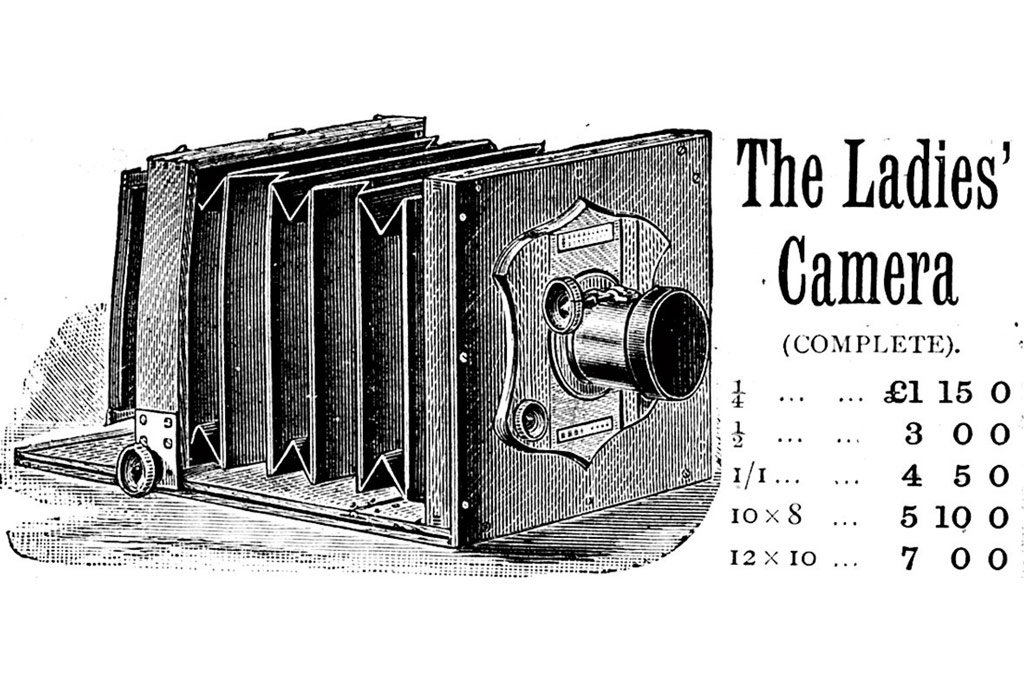

Photographers were mostly men, even though AP – probably in an effort to drum up readers – pointed out in its first edition, ‘ladies make excellent manipulators.’ Photography, until then, had been a business for professionals, rather than a hobby for amateurs. But by 1884, with photographic processes becoming easier to use, that first issue announced that the number of amateur photographers in the UK now vastly exceeded professionals.

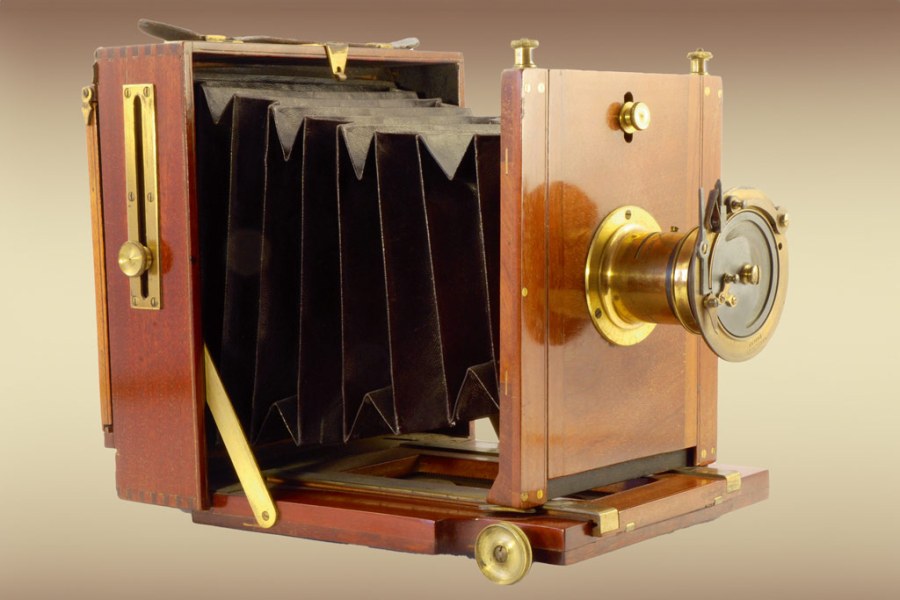

With a few exceptions, cameras at this time were little more than lenses with adjustable apertures mounted on panels at the front, linked by bellows to plate-holding panels at the back. Once a photographer had purchased a camera, he tended to stick with it, with his interests more likely to be in how chemistry and new processes were changing to make it simpler to take better pictures.

What has come to be acknowledged as the first photograph was taken in France in 1826 with a totally impractical process and an eight-hour exposure. It wasn’t until the advent of the daguerreotype process in 1839 that photography for the masses really took off. But even then it was more a job for a professional, and the processes involved were not just difficult, they were downright dangerous if the chemistry wasn’t handled correctly. The technicalities grew easier with various procedures that followed before the arrival of the wet plate process. This involved coating a plate in a darkroom immediately prior to exposure, using it in the camera while still wet and developing it straightaway after.

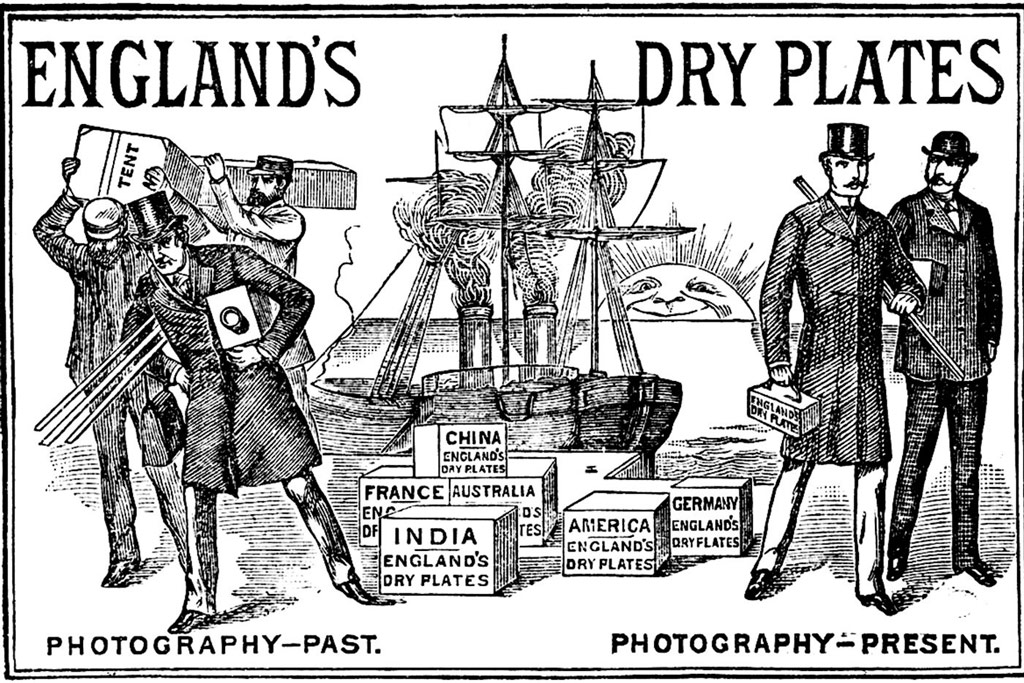

By 1884, the wet plate process was hanging on by its fingertips, still used for some specialised purposes, but by this time most photographers had switched to dry plates. Unlike wet plates, these were bought in advance, used when needed and processed later. One major consequence of their introduction was that their relative ease of use introduced more amateurs to the joys of photography.

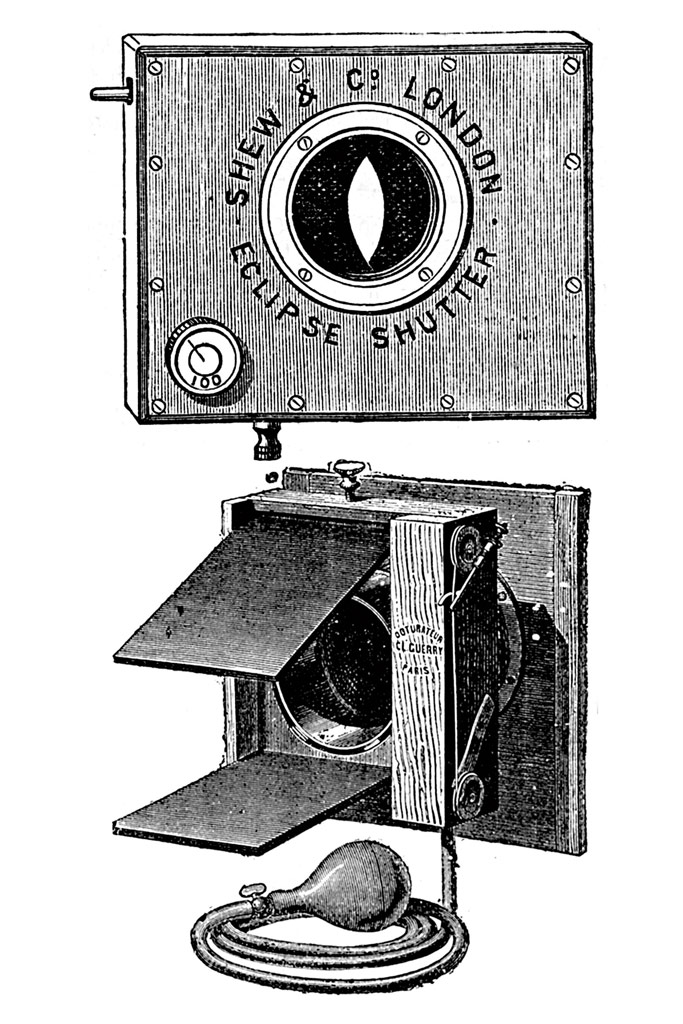

The new dry plates were up to 30 times faster than wet plates, meaning exposures could no longer be made by the tried-and-tested method of removing the lens cap and replacing it after the required number of seconds. Exposures could now be measured in fractions of a second. So shutters began to appear, sold as add-on accessories.

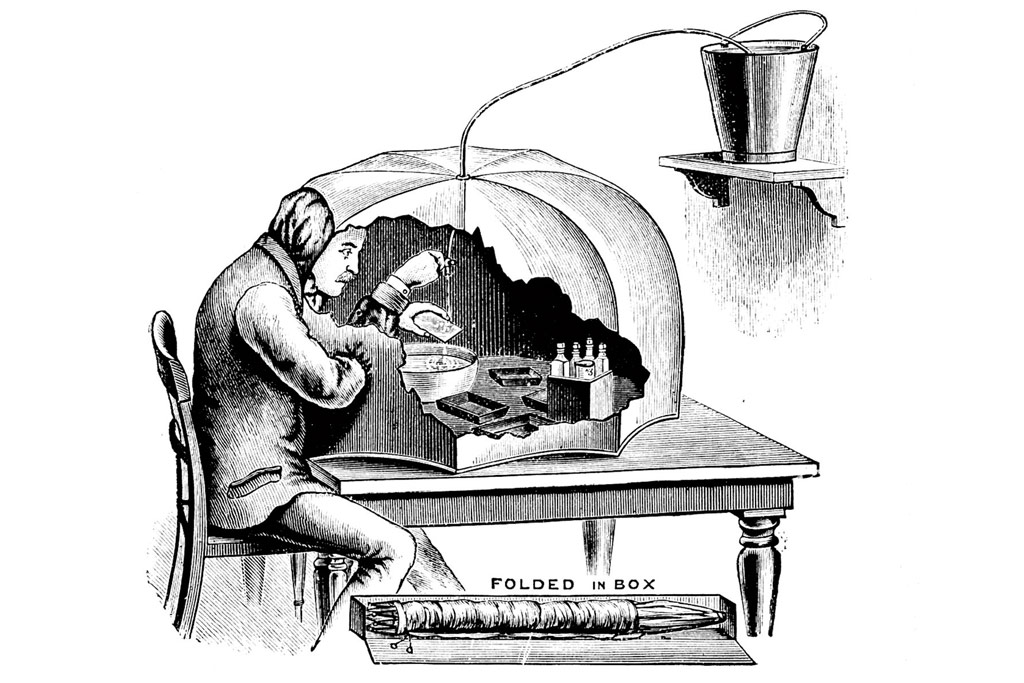

Early shutters took the form of sliding plates or flaps that opened and closed, but the year after AP was published, the English Lancaster company patented the first rotary shutter. This used a rubber band, whose size and strength controlled speeds from slow up to 1/100sec. Even so, making an exposure was a slow procedure. It went like this…

- A glass plate of an appropriate size according to the camera in use, was loaded, in a darkroom, into a plate holder. This was like a flat box with a sliding dark slide covering the light-sensitive plate.

- The camera was set up on a tripod.

- With the lens cap removed or the shutter opened and the lens aperture adjusted to its widest setting, the image was focused on a ground-glass screen at the back of the body.

- The lens cap was replaced or the shutter closed.

- The appropriate aperture was set on the lens.

- The ground glass screen was moved away and the plate holder inserted in its place.

- The dark slide was removed.

- The exposure was made.

- The dark slide was slid back into place and the plate holder removed and stored.

- Later, in a darkroom, the plate was taken from its holder and developed.

Photography in 1884 was not a cheap business. George Hare’s New Patent Camera would have set you back anything between £4 10s (£4.50) for a 5x4in size model up to £13 5s (£13.25) for a 15x12in size. That doesn’t sound much until you know that the average weekly wage for a man was around £1. For those who could afford to buy a camera, they still had to run it. The cost of a dozen dry plates varied around 1s 6p (7½p) for quarter-plate size (4¼x3¼in) up to 10s (50p) for 10x8in.

Although, as AP commented in that first issue: ‘At the present time dry plates are manufactured by hand, but already an invention has been patented for coating them mechanically, and it is quite possible as demand increases the whole of the process will be conducted by machinery. This will have the inevitable result of reducing prices.’

Good job the cost of that first AP on 10 October 1884 was only tuppence (slightly less than 1p in today’s money).

Related reading:

- 140 years of Amateur Photographer

- 140 years – a lifetime of landmark cameras

- 140 years – What AP means to me

- Life in the past lane – Photography in 1884