Generations: Portraits of Holocaust Survivors is a touching and poignant exhibition. Amy Davies caught up with three of the photographers involved to find out more

Having been on display at London’s Imperial War Museum already, the response to Generations: Portraits of Holocaust Survivors has been immensely positive, according to show curator Tracy Marshall-Grant. To mark Holocaust Memorial Day, the exhibition has moved to RPS Headquarters in Bristol, and is now available to view until 27 March 2022, so if you didn’t get a chance to see it in London – there’s plenty of time.

The exhibition was created in a partnership between the IWM, Royal Photographic Society, Jewish News, the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust and Dangoor Education. It brings together 13 contemporary photographers, all members and Fellows of RPS, and images by the RPS patron, Her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cambridge, who has two specially commissioned portraits in the exhibition.

A series of individual and family portraits, the aim of Generations is to celebrate the lives and legacy of those who suffered unimaginable, life-altering experiences during the Holocaust. The survivors presented here all made the UK their home; the resulting images are a celebration of the rich lives they have lived and the special legacy which their children and grandchildren will carry into the future.

© The Duchess of Cambridge. Steven Frank, aged 84, with his granddaughters Maggie and Trixie. Steven survived multiple concentration camps as a child. On display as part of the Generations: Portraits of Holocaust Survivors exhibition.

The systematic persecution of Europe’s Jews between 1933 and 1945 is estimated to have taken six million lives. For those left behind, the impact and memory of this devastation changed everything. Originally planned before the pandemic to coincide with the 75th anniversary of the end of World War Two and the liberation of the concentration camps, the project was inevitably delayed by various lockdown restrictions.

As a result, most of the portraits were taken in the spring of this year, following careful planning and adherence to the latest guidelines, and with some tweaking to the original concept. Additionally, some of the work changed – but not necessarily for the worse – by dint of having such restrictions.

Some photographs were taken outside, pre-planning was arranged online rather than in person, and the photographers had to rethink how to approach the issue in a sensitive way while also ensuring that a positive message shined through.

Tracy Marshall-Grant says, ‘Each portrait shows the special connection between the survivor and subsequent generations of their family and it emphasises their important legacy. The portraits, by leading contemporary British photographers, seek to simultaneously inspire audiences to consider their own responsibility to remember and to share the stories of those who endured persecution. ‘It creates a legacy that will allow those descendants to connect directly back and inspire future generations.’

Photographers on display include Sian Bonnell, Arthur Edwards, Anna Fox, Joy Gregory, Jane Hilton, Tom Hunter, Karen Knorr, Simon Roberts, Michelle Sank, Hannah Starkey, Frederic Aranda, Jillian Edelstein and Carolyn Mendelsohn – the latter three spoke to AP for this piece.

Frederic Aranda

Specialising in individual and group portraiture, Frederic Aranda was one of the first photographers to be asked to join the Generations project. He has worked with some huge international clients, has won multiple awards and published several books. Visit fredericaranda.com.

As a Jewish photographer, Frederic Aranda also had some links with the community that enabled him to bring participants to the project, as well as be matched up with some by the organisers. It was vital for Frederic that his images had one important message. ‘My approach from the start was decidedly very positive and upbeat.

© Frederic Aranda, Ben Helfgott MBE with his grandson, Sam. Ben was a champion weightlifter after arriving in the UK

I didn’t want to take dreary portraits of people looking sad and depressed. I’m Jewish myself so I’ve been thinking and talking about the Holocaust my whole life and it’s a subject very close to my heart. Now is a time to celebrate being alive and the fact that life can find ways of continuing despite adversity and horror. I was therefore determined to ensure my portraits were not just clichés of a survivor looking depressed and dark.’

Most of the portraits were shot in spring of this year, with good weather being on their side – being outdoors added to the sense of the participants feeling comfortable and happy. One of the portraits in particular – that of Freddie Knoller – stands out for Frederic. ‘I was invited to his house, into his garden on his 100th birthday.

© Frederic Aranda, Freddie Knoller BEM photographed on his 100th birthday with his wife, daughters and grandson

They had set up a party and I was asked to go there in advance to photograph him and his relatives before everyone else arrived. It was one of the most joyful pictures, with the party atmosphere, celebrating his centenary and playing the cello – something he used to do during the Holocaust.

‘The last thing anyone wants is to see a Holocaust survivor looking sad – we know what they’ve been through, and we make sure we know that by the captions and by telling their story in the text. I think for a portrait with their grandchildren it’s important for them to look happy.’

As with the other photographers involved in the project, for Frederic it was a huge privilege.

© Frederic Aranda, Susan Pollack MBE with her granddaughter, Emily. As a teenager Susan was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau with the rest of her family

‘I don’t think [the organisers] knew that I was Jewish when they asked me to do this, I don’t think they had any idea just how meaningful it would be for me. I’m not religious, but culturally I’m Jewish and I never thought I’d be able to photograph Holocaust survivors – I just never saw it happening. How it all just landed in my lap, I couldn’t be more grateful – for me it was some of the most profound encounters I’ve ever had.’

Jillian Edelstein

Based in London, Jillian Edelstein has won numerous awards and had her portraits published in a huge number of publications and for various high-profile clients. She is one of the RPS’s ‘Hundred Heroines’. Visit jillianedelstein.co.uk.

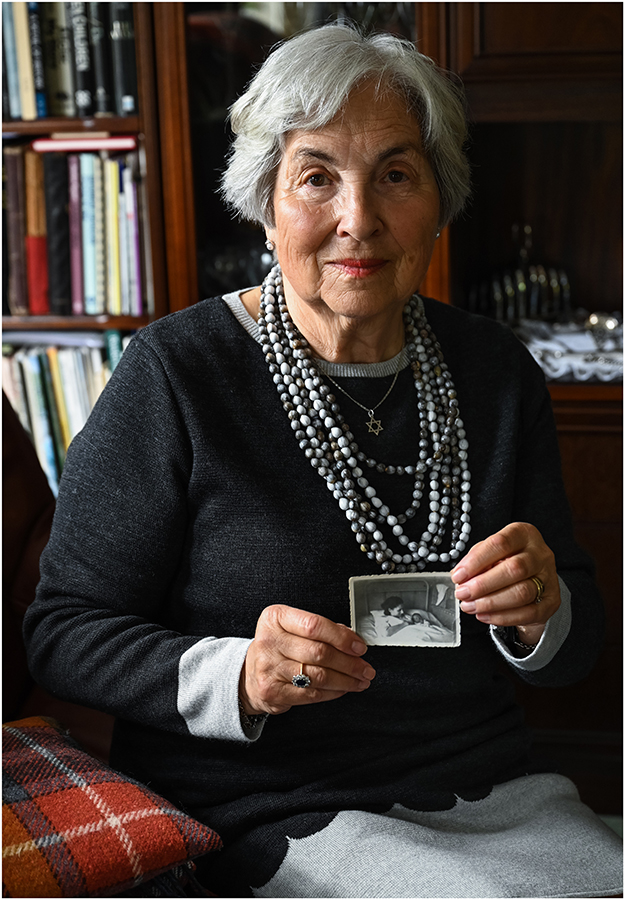

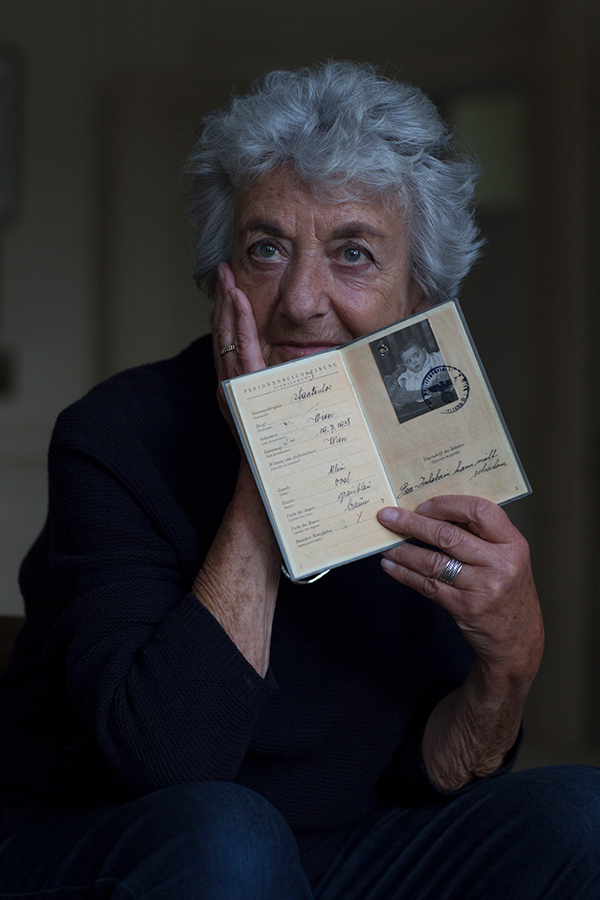

For Generations, Jillian photographed a number of different survivors, two of which she brought to the project herself. As she explains: ‘I worked with Philippe Sands, and one day while having a drink with him, he said, “Gosh you’ve got to photograph my mother, because we’ve just found her baby passport image.”

© Jillian Edelstein, Born in Vienna, Ruth Sands was smuggled to France before eventually being reunited with her parents after the war

It’s this rather extraordinary image of her kind of sitting up, and there’s the Reichstag stamp – it was very intriguing, so I had to include it in the portrait of Ruth Sands. ‘The other was Elsa Shamash – I know her daughter so I’ve known her for years. The rest of the participants were matched up with me by Tracy [Marshall-Grant].’

Each of Jillian’s portraits were taken during the same five or six-month period, generally with a visit or a phone call beforehand. One of Jillian’s portraits was taken outside, but she says most of the subjects were quite open to doing the best they could to get a great photograph. Some subjects were visited twice.

© Jillian Edelstein, John Hajdu with his teddy bear ‘Teddy’ who came out of Hungary journeying with him as a refugee to the UK

‘I had changed my thinking on how I was going to work towards getting a final image,’ she explains. ‘They were all completely open to it and giving, quite prepared to give time, which is very welcome.’

Working on a personal family project recently, Jillian spent some time with refugees at Calais. She also visited a small town outside Vilnius, home to a Jewish community that once included her paternal grandmother. As such, she feels not only a personal connection to the work, but a number of questions are also raised.

© Jillian Edelstein, Elsa Shamash was born in Berlin in 1927 and came to the UK via the Kindertransport in 1939 with her brother

She says, ‘Part of me became quite intrigued with the idea of what you would do if you had very little notice that you had to leave your home – what would you take. There was this discussion about what was a possession, what was memorable; something, that on the theme of positivity would evoke happy memories for them, but also keep them moving forwards in their journey. For example, with John Hasdu it was the teddy bear he took out of the ghetto.’

For Jillian, projects like this and her involvement with it are incredibly important. ‘I think it’s vital. As humans, our memories seem to be very short and they can shift and change in a heartbeat, and it’s quite scary to see that.’

Carolyn Mendelsohn

After originally training as an actor and a filmmaker, Carolyn Mendelsohn turned to photography in 2008 while raising her young family. She has since won several awards, been exhibited numerous times and published her book, Being Inbetween, in 2020. Visit carolynmendelsohnphoto.com.

Based just outside Bradford, Carolyn was matched up with Holocaust survivors in the North of England, but she had some say in who she chose. ‘We were given a list and I literally looked at the names and thought – this person sounds interesting, just on the basis of a name! One of them I was already aware of – Rudi Leavor – as he was a really influential figure in Bradford so I thought this was a really incredible opportunity to meet him and amazing to take his portraits.’

The portraits were all taken this spring, with communication taking place prior to the sitting. Carolyn explains, ‘Because the theme is generations, I said to Rudi it’d be really nice if a couple of your grandchildren could be part of it. Rudi, being Rudi, said I’ve invited nine of them – and a couple of great-grandchildren, because I couldn’t leave any of them out.’ The portraits take on extra poignancy as sadly, Rudi died just a few weeks after his and Carolyn’s portrait session, on 26 July.

As with the other photographers involved, Carolyn can’t overstate the importance of a project like Generations. ‘Giving a face and a voice to people who have been through these extraordinary things brings the reality of what happened into full view. These people are very elderly and it’s easy to forget that people are still affected by this. The people that I met are extraordinary individuals, rather than just something from a history book – I learned so much by doing it.

‘What’s lovely about this exhibition is that you have 13 photographers who are well known in their fields, who all have a very distinct style. It’s a really beautiful thing to be part of, and a really positive thing too – about how life goes on, how generations continue and how people continue after experiencing something so devastating.’

© Carolyn Mendelsohn, Rosl Schatzberger, aged 96, with her daughter. Rosl holds a portrait of her mother-in-law, Ida, who was killed at Auschwitz

Interestingly, just like Jillian and Frederic, Carolyn also has a personal connection to the work. ‘My family have a similar background, from Germany and Lithuania, some who escaped war, some who were killed in it. I don’t think we were selected because of this reason, and for me, I’ve just been an individual photographer not really connected to my own personal history before. By my involvement with this, it really was important and enabled me to connect to my relatives in a way that I hadn’t before.’

Generations: Portraits of Holocaust Survivors

Generations: Portraits of Holocaust Survivors runs at RPS Bristol from 27 January 2022 until 27 March 2022 – see the RPS website for the latest information regarding opening times and ticketing.

Generations: Portraits of Holocaust Survivors

Related articles

Best photography exhibitions to see in 2022

Winners revealed in Holocaust Memorial Day photo competition