The Photographers’ Gallery has given three floors to a Daido Moriyama exhibition. So what’s so special about this octogenarian Japanese photographer? Geoff Harris finds out more about his 60-year career and influential street photography.

First: the easy bit. Daido Moriyama, born 1938, is an internationally famous Japanese photographer, best known for his gritty black & white street photography and contributions to various avant-garde and experimental publications in Japan’s post-war period. The Photographers’ Gallery, one of London’s most prestigious photographic centres, is hosting the first UK retrospective of Moriyama’s work, starting on 6 October.

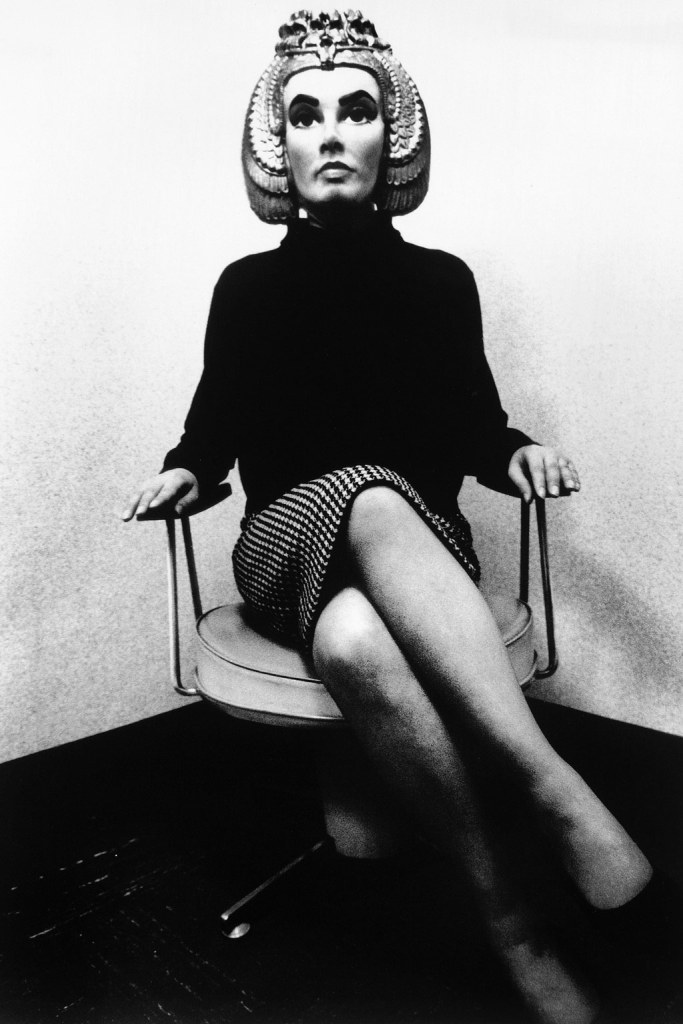

That was easy enough, but trying to define the work of Daido Moriyama, or the essence of what makes him so special and influential, is much harder. Like the masks in Noh theatre, Moriyama has taken on various enigmatic identities over his six-decade career.

The young man from Osaka who endures living in Tokyo flop houses to learn from the experimental photographer Eikoh Hosoe, but doesn’t take a single picture of his own for three years; the cultural bomb-chucker, railing against Western-style photojournalism and bringing out a book (Farewell, Photography) that includes lots of ‘spoiled’ images and shots of analogue photography detritus; the Japanese Jack Kerouac, buggering off around the country in an old Toyota; the artist who talks about ‘desire’ and the erotic pull of photography while also comparing himself to a loner, a stray dog; the grand old man of Japanese photography, happy to share tips and advice in a banal-sounding (but wonderful) 2019 book called How I Take Photographs.

Moriyama – A new understanding

What I find fascinating about Moriyama is that his work can influence and inspire on many different levels. Forget geisha and Mt Fuji, a lot of Western photographers now come back from Japan trips with gritty, monochrome, clearly Moriyama-esque images of dive bars and back streets; at the same time, his work is like catnip to photography academics and historians, who wear out their keyboards pondering its cultural significance.

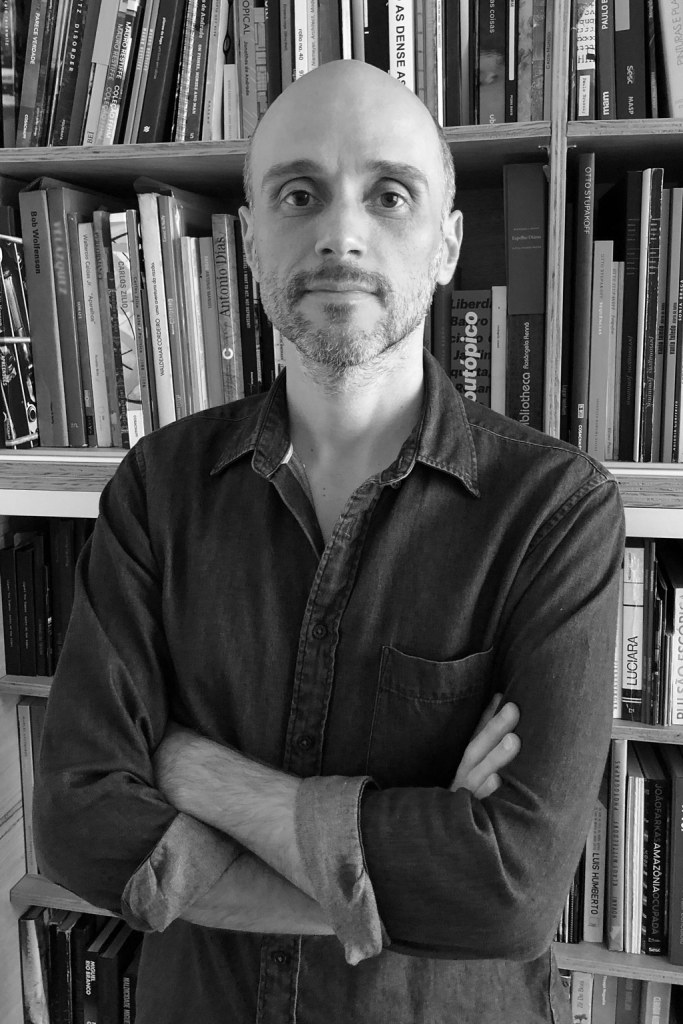

So, not an easy photographer to pigeonhole in six pages. To get a better sense of the importance of Daido Moriyama, and why The Photographers’ Gallery has pretty much given the place over to him (bar the café and shop), we caught up with the exhibition’s chief curator, Thyago Nogueira from the Instituto Moreira Salles in São Paulo, Brazil.

‘The idea of this first UK retrospective is to offer a new understanding of Moriyama’s work and legacy,’ Nogueira explains. ‘There is something very radical, original and conceptual in his photography, and this was not clearly understood. Moriyama was working in a cultural context and framework that was totally different to the Western European and American perspectives.’

Nogueira, a self-confessed admirer as well as a rigorously professional curator, started to research Moriyama’s work three years ago. He’s very clear that Moriyama must be seen in his cultural context. ‘In Japan, there was a school of photography that was born in the medium of mass communications, not in galleries or institutions. After the war, it took a long time for Japanese academic institutions, galleries and universities and museums to recover, or develop as we understand them. There was less veneration for vintage art works and valuable photographic prints, and this, I believe, gave Moriyama an advantage. There wasn’t the devotion for artworks that we inherited from the European tradition.’

Daido Moriyama – Striking to the heart of photography

Another key goal of the exhibition is to explore how Moriyama’s approach has changed. ‘He’s now in his 80s and has spent a long time thinking and writing about photography. I ended up researching the context of the amateur photography magazines that were popular in Japan in the ’50s and ’60s – this was the fertile soil where some of Moriyama’s ideas originated.

‘The exhibition shows how Moriyama has been trying to address one fundamental question: what is the essence of photography, what defines this visual language that we love? He has given different answers throughout his life. A lot of the questions we are asking now, around AI and digital photography generally, were being asked by Moriyama when he was a young man.’

All well and good, but what can modern photographers learn from Moriyama? ‘He’s tried to show that the most radical aspect of photography is its banality. He has tried to overcome his ego and his pretentions as an artist and to “undress” himself from the accumulated clichés that still burden photographers. He felt that the more he could duplicate the world through his camera, the more radical and inventive his photography would be. For Moriyama, he never felt his understanding on the world was somehow “higher” because he was an artist.’

Moriyama began his street photography by recording the big social changes and dramas taking place in Japan after the war, notably the effects of the American occupation and impact of consumerism and capitalism. ‘But he soon gave up on the idea that a photographer could somehow make sense of what was happening, or even use his images to fight social injustice. He just wanted his camera to replicate the world and replicate the feelings he had in this world. As he got older, his approach become less ordered, he would just wander the streets and sometimes take exposures without even looking through the viewfinder. He was trying to work as a Xerox machine, copying reality.’

People tend to look at Moriyama just as a street photographer, but Nogueira is adamant that he is also a conceptual photographer, trying to define the ‘essence’ of the image through his photography. ‘Walking around Tokyo was a way to do this, but he was also investigating his emotions and his memories. He is not really looking at the city per se, but at his inner territory – the streets of his mind. He has the camera with him to record this, the moment when what’s in front of him somehow chimes with his emotions and memories. That for Moriyama is true street photography.

‘Also, despite his travels, he tries to show that you don’t actually need to go far – he’s been exploring the same neighbourhood in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district over and over and over again. A deep dive into your own neighbourhood and your own feelings can generate something new.’

A recurring theme in this feature is Moriyama’s incredible work ethic, and this should also inspire other photographers. ‘He is now producing a magazine called Record, three or four times a year, with all sorts of pictures and snapshots,’ Nogueira adds. ‘Stripping away pretentions and making himself “horizontal” to reality is what makes his photography so beautiful and interesting.’

Daido Moriyma – Dog days

Moriyama was born near Osaka, Japan’s second city, to parents who moved around. He cut his teeth working alongside the great experimental photographer Eikoh Hosoe and the documentary photographer Shomei Tomatsu, but soon realised he didn’t want to be a photojournalist. ‘He was sceptical that a photojournalist could just go to a place and somehow understand it, or tell the whole story, by taking a few images,’ Nogueira elaborates. ‘Moriyama started to experiment more and more and got involved with a bohemian underground theatre and started to develop his own ideas for looking at the world in a more subjective way. ‘

As a good introduction to Moriyama’s huge and complex canon, Nogueira recommends Memories of a Dog. ‘It’s a beautiful series, where Moriyama goes to different villages from his childhood, using the camera to connect images and emotions from his youth with what he was seeing in front of him. In Japanese, the name of his current magazine, Record, also plays on the word for “memory”. Is photography a document, or a projection of our own memories? This preoccupation diverges him from his contemporaries.’

As we’ll see elsewhere, other photographers have noted Moriyama’s preference for small, cheap cameras, but this is about more than staying unobtrusive on the street. ‘He doesn’t care about the camera, it’s nothing to do with technical gear or virtuosity. Moriyama started out with cameras people gave him or he borrowed, and even now just uses a small point-and-shoot digital camera. He is always running away from his ego and any idea of himself as an artist.’

So why, exactly, does Moriyama continue to exert such a lasting influence on many Western photographers? ‘Because he has investigated image-making so deeply. Even when he is photographing other cities – like São Paulo, where I live – they all look like Tokyo! So yes, the way he’s created this dark, grainy, very introspective style has had a huge influence and you can instantly see other photographers trying to imitate him. Whenever you go deep into an art form you open a new form of vision, a new way of looking at the world and trying to organise it. It is only natural that people start to use the same ideas – it’s like William Eggleston’s pioneering use of colour.’

Daido Moriyma – Pictures on a page

Nogueria also wants the exhibition to remind people that Moriyama is a photographer who’s always shot with publication in mind, be it in magazines or photobooks, rather than, say, just taking images to hang on walls. ‘The printed matter is the core of the exhibition, and it’s very important to understand how Moriyama has been working with the printed medium. Even over three floors at The Photographers’ Gallery, it’s been a real challenge to convey how his work has developed over the different decades, so we present a wide variety of printed matter. He also likes the sensuality of books and magazines.’

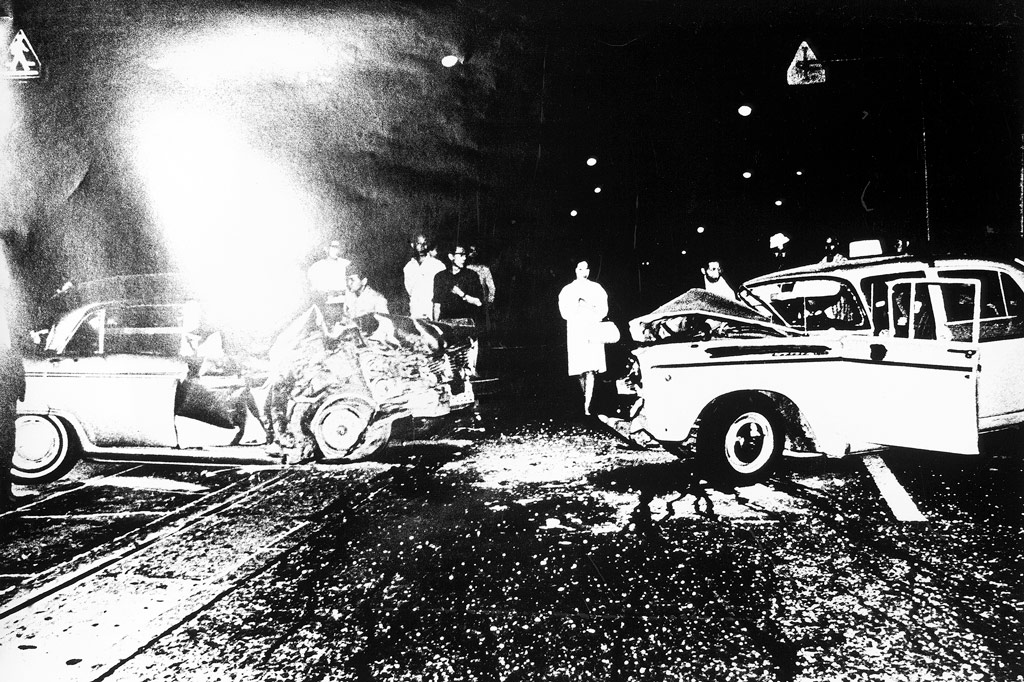

So what are Nogueira’s favourites from Moriyama’s almost infinite body of work? ‘When you dive into such a rich creative output, this is very hard to answer, like saying what is your favourite note in a symphony. But I am very fond of a series called Accident from 1969. Via a magazine, Moriyama decided to investigate the nature and essence of news photography. He would choose an aspect of photojournalism and twist it completely – the death of Bobby Kennedy in 1968, say. He’d say, “I was not there, I cannot relate to this, but I’ve been influenced by images that come to me in Japan.” So he rephotographs and Xeroxes TV and newspaper images.

‘Or, he investigated the newly popular zoom lenses as a way of surveying people in the street, like the Hitchcock movie, Rear Window. He also looked at how publishers intrude into the lives of celebrities, or he rephotographed public safety posters about car accidents in an experimental take on photojournalism.’

Despite his prodigious work ethic, even Moriyama has been forced to slow down. ‘The pandemic hit him hard, and he can’t move around so much now, but he’s very happy this exhibition is taking place,’ Nogueira concludes.

As are we. The final word should go to Moriyama himself. Trying to find a closing quote that sums up his approach is not easy, but this, from the highly recommended book, How I Take Photographs, will do for now. ‘Get outside. It’s all about walking, walking, walking. The second thing is, forget everything you’ve learned on the subject of photography for the moment, and just shoot. Take photographs – of anything and everything, whatever catches your eye. Don’t pause to think.’

Under the influence of Daido Moriyama

Daido Moriyama’s influence on contemporary photography, particularly street work, has been huge. We spoke to a few AP contributors to find out what he means to them.

Peter Dench

Growing up in the 1980s I was aware of Japan, but didn’t fully comprehend it. I’d moved to London after graduating in Photographic Studies and not studied a single frame of Japanese photography. Now seemed the right time and my entry point was Daido Moriyama’s work and in particular his A Hunter (Karyudo) series – it even inspired me to do my own road trip from London to Land’s End!

Moriyama’s photography challenged all the academia I’d learnt. It was rule-breaking and fast-paced, it defied photojournalistic conventions and gave you a proper smack across the senses. Some of his images in A Hunter linger in my mind, including a barefoot woman in a white dress running through debris, beach boys sunbathing side by side and his most famous picture of a bedraggled, growling stray dog turning its head towards the camera – which took on a life as a symbol for post-war Japanese culture.

As I developed my own approach and style I started to reject many of Moriyama’s techniques, preferring to look through the viewfinder to consider, compose and crop. I pulled back on over-shooting and aimed to press the shutter only when certain there was potential for a great capture that would fit the narrative. Uncertainty had become my nemesis.

Yet I still have my Moriyama moments when I remember it’s okay for a photograph to have a bit of grain, that it can be garish, blurred, out of focus with blown-out highlights, have harsh contrast, a skewed look and that there is beauty in imperfection. When I wonder what the point of photography is, I re-engage with the raging rawness of Master Moriyama.

Brian Lloyd Duckett

I have followed Moriyama’s work for a long time. I’m very keen on black & white photography, and much of his notable work in this format. That drew me to him. Also, Moriyama is a rule-breaker, he doesn’t give a fig, and I too rail against convention. He’s not bothered about pretty composition, perfect exposure, sharpness or grain, etc. For him, photography is all about feeling and soul.

Why do any of us shoot black & white in street photography? Some do it for nostalgia, some because they like the aesthetic, but for Moriyama there is a deeper meaning – he sees it in a more abstract and symbolic way and once said it ‘takes you to another place’. He also called it ‘erotic’, which is an interesting choice of words. So Moriyama shoots black & white with a real sense of purpose – it’s not a lazy afterthought or a way to salvage a mediocre colour shot. For him it’s a creative choice.

Many people don’t get Moriyama. The thing to remember is that he shoots for the publishing world, rather than the art world. To the uninitiated, his work seems like random snapshots, but he is challenging our conventional aesthetics and enjoys being provocative. He had a joint retrospective at the Tate with William Klein in 2012, which is apt, as both worked in a very raw way, rather than presenting a filtered, manicured version of life. One of his most famous images is of a stray dog, and Moriyama also wanders around like a stray, with not much thought or planning, sniffing out pictures.

He’s also got a tremendous work ethic and has published about 150 books, which is an astonishing output. Moriyama shows you can’t just walk around the streets for a couple of hours and give up. He would work day and night, just needing to know what’s around the next corner or down the alley. If you keep at it, serendipitous things will happen. Then, rather than walking around with a bag full of Leicas, he has a tiny camera, he’s no threat to anyone, people don’t turn away. You can buy an old point-and-click camera these days for a song, so be like Moriyama – that’s all you need.

Gavin Mills

Moriyama’s name is synonymous with the raw, unfiltered essence of street photography. His work not only redefined the boundaries of Japanese street photography but also left an indelible mark on the global photography landscape. My wife, Noriko, is Japanese so our trips became extended holidays, providing me with ample opportunities to explore the city’s vibrant streets through my lens. Tokyo, in particular, stands out as one of the most inspiring locations that I’ve ever encountered for street photography.

Much like Moriyama’s street photography, my work aims to capture the often-overlooked and raw aspects of urban life. I find inspiration in the city’s contrasts and contradictions – serene moments hidden amid the chaos; human connections forged in a crowd; the fleeting expressions that reveal the soul of a bustling metropolis.

One of the most compelling aspects of Moriyama’s work, which resonates deeply with my experiences, is the exploration of the human condition in an urban environment. His photographs are filled with anonymous faces, blurry figures, and fragmented scenes that evoke a sense of anonymity and isolation. This portrayal mirrors the complex tapestry of emotions I’ve witnessed among modern city dwellers, emphasising the disconnection and isolation that can exist amidst the hustle and bustle of urban life – the paradoxical blend of loneliness and togetherness that defines contemporary society. His photographs are not mere snapshots; they are windows into the human experience, an exploration of the soul of Japanese city life. His work serves as a testament to the power of photography to convey the raw, unfiltered essence of our world and the depths of humanity.

Mick Yates

Japanese photography has always interested me, even before I lived there. Yet it still seems under-appreciated in this part of the world. Moriyama is arguably one of the greatest living street photographers. Born in 1938, he continues to astound with his eye and his output, being one of the most prolific photo book producers, and a perpetual traveller. Whilst some single images have become ‘iconic’, I tend to see his work in a series, as storytelling. A 2017 interview with Bree Zucker in BOMB magazine, shows that for Moriyama, documentary is not just a depiction of ‘reality’, but a subjective activity: ‘For every single photo I take, some fragment of my memory has probably made its way in there. Then the viewer also projects his or her own memory onto it. Sometimes the photograph has more impact on the beholder than the taker.’

Mick, who is the co-founder of the Photo Frome Festival, has written very extensively on Moriyama – we can’t do justice to Mick’s erudition and insight here but yatesweb.com/daido-moriyama-record is a good place to start.

The Daido Moriyama retrospective is on until Sunday 11 February 2024 in the Photographers Gallery in London.

Best photography exhibitions to see in 2023

Related reading:

- Complete street photography guide

- Black and white street photography: Tips and techniques from the experts

- Analogue street photography tips

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.