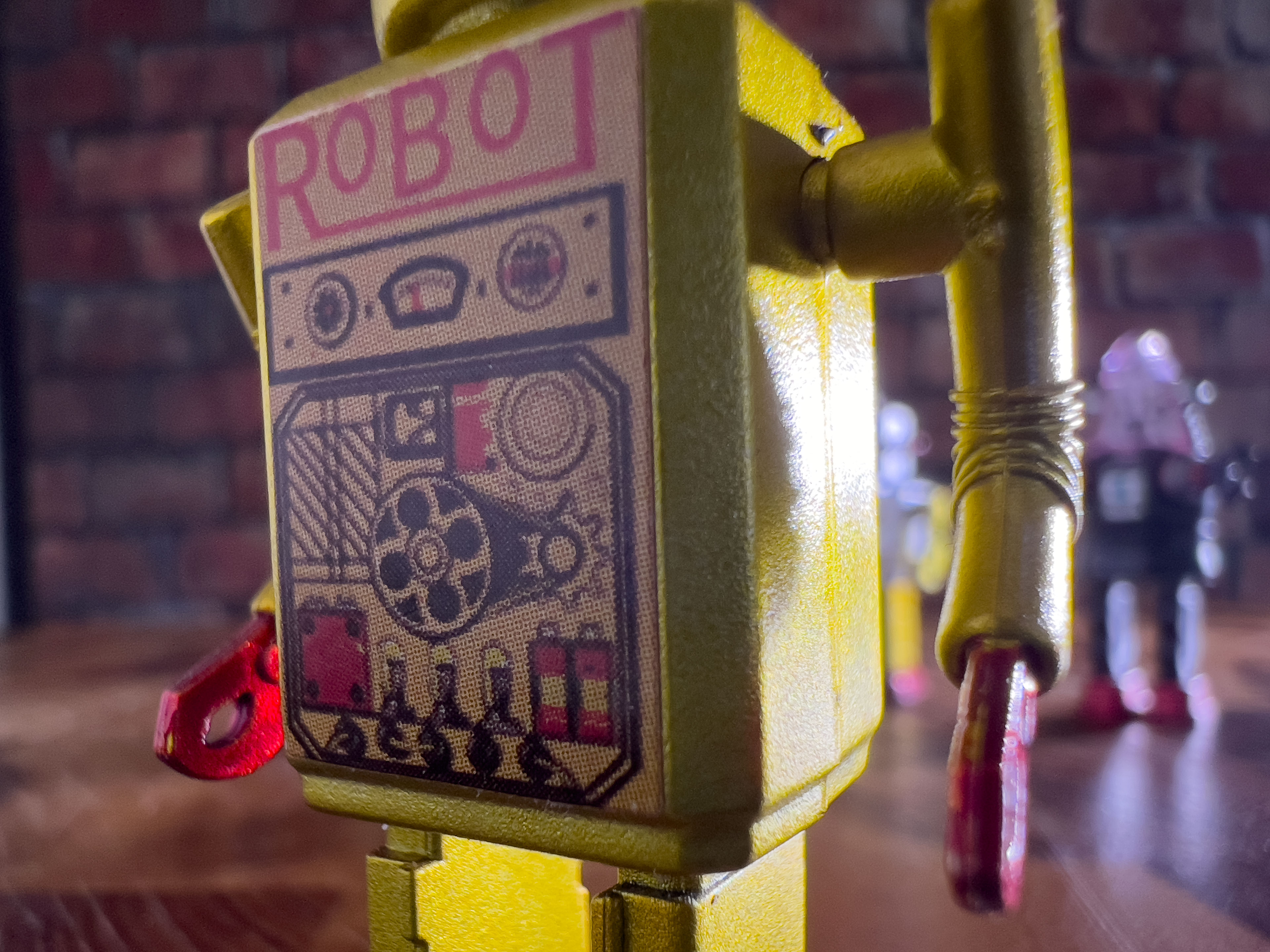

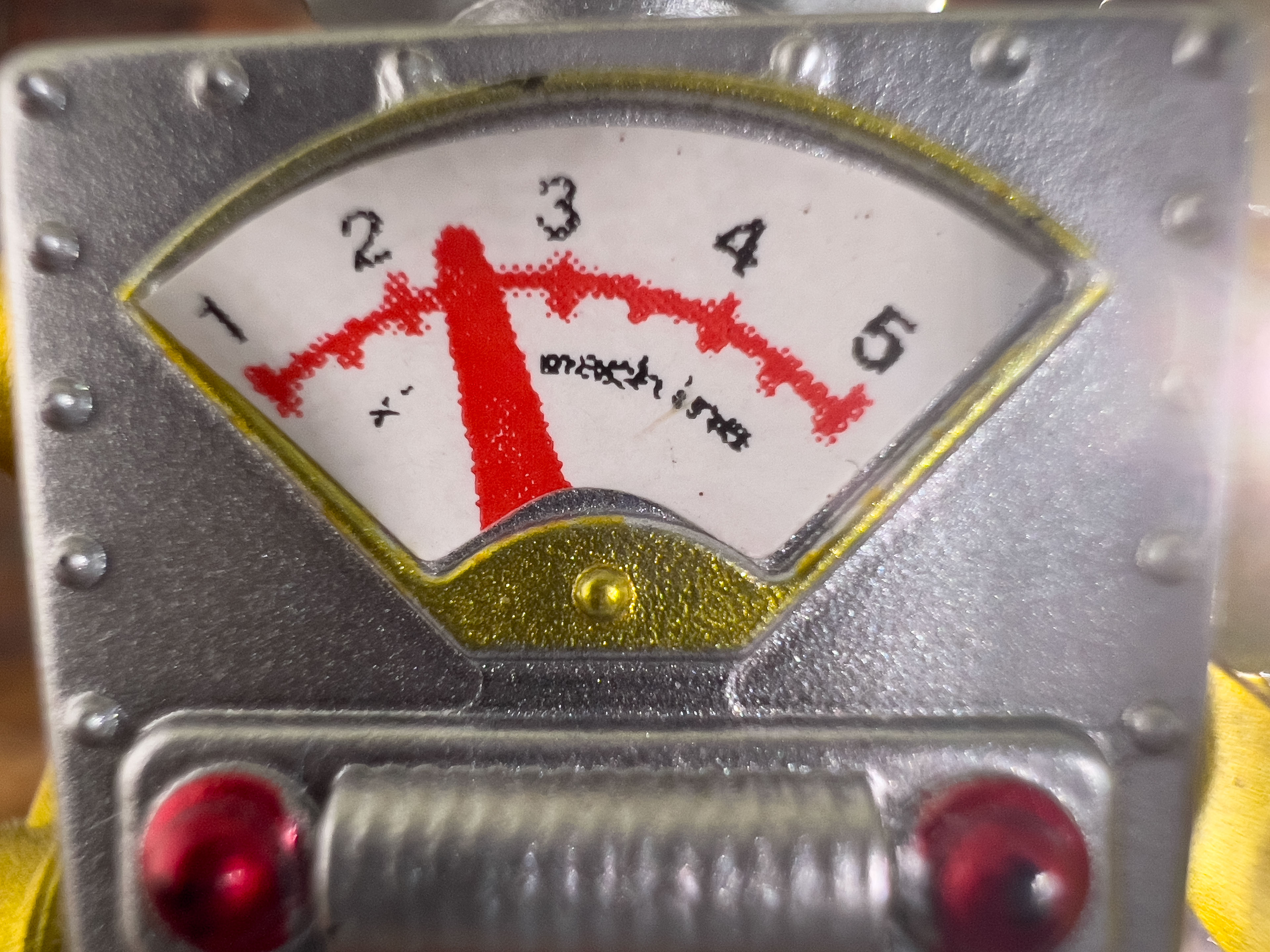

Lots of smartphones have ‘macro’ modes. Here’s a selection of photos taken using my phone’s ‘macro’ mode. As you can see, you can get some really remarkable magnification of tiny objects, and you can often fill the image frame with an object in the same way as you can with a true macro lens and a proper camera.

Even so, experts will argue this is not proper ‘macro’ photography. So let’s dive in and see what this word actually means – and whether it’s still useful or relevant for the different camera types we use today.

What does ‘macro’ actually mean?

It’s all down to the precise technical meaning of the word. These days, the term ‘macro’ is often used to indicate just about any kind of close-up photography, or photographs of small objects. But where does close-up photography end and macro photography really begin? It’s all down to magnification.

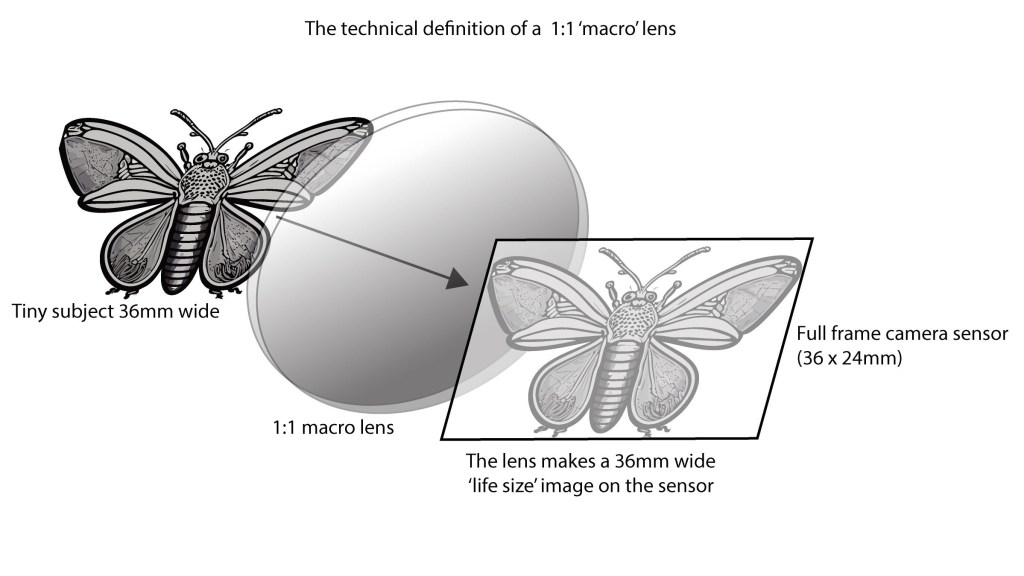

The strict definition of ‘macro’ photography is where the object you’re photographing is reproduced at the same size (or larger) by the lens on the sensor. This is the so-called 1:1 reproduction ratio you hear about a lot in serious macro work. In regular photography, the lens is capturing a much larger scene or subject and shrinking it to fit on the sensor, but in macro photography you’re so close that it’s not shrinking your subject at all.

Here’s an example. Let’s say you’re photographing an insect that’s 36mm long (eek). A full frame camera has a sensor that’s also 36mm wide. If you take the photograph using a 1:1 magnification with a macro lens, the insect will completely fill the sensor width.

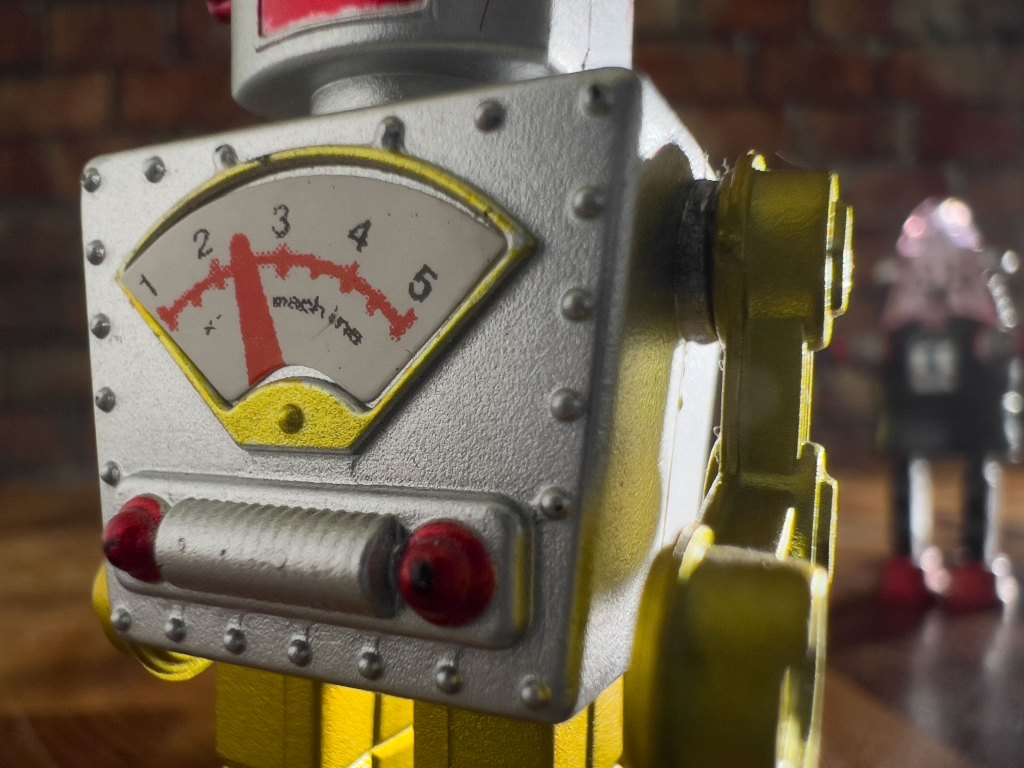

The example shots that go with this article are of a set of four toy robots less than 2 inches/25mm high. Some of the shots are ‘macro’ images, some are close-ups. It’s all a question of magnification, and sometimes the distinctions get blurred.

How are ‘macro’ lenses different to regular lenses?

There are only a couple of differences between a regular lens and a macro lens. One is that a macro lens is designed to focus much closer than an ordinary sort – it’s as simple as that. If you could make a regular lens focus closer and closer and closer it would reach the point where it becomes a macro lens. However, it’s impractical to make regular lenses focus this close – the focus mechanism and internal design of macro lenses is highly specialized.

There’s another difference. All lenses are optimized for certain types of subject matter and, indeed, certain focus ranges. Regular lenses tend not to perform as well at very close focus distances, whereas macro lenses are optically optimized for this kind of work.

So while in the old days you could get stackable extension rings or ‘bellows’ to move the lens further from the camera body and hence focus closer, this does affect the results. It’s why, incidentally, you could also get ‘reversing rings’ to make the lens face the wrong way. It sounds strange, but it helps.

With today’s advanced lens designs and optimizations, it’s no longer feasible to use extension rings, bellows or reversing rings while still maintaining optical quality and all the electro-mechanical lens-body communications modern cameras use. These days, if you want to shoot macro you need to invest in a macro lens.

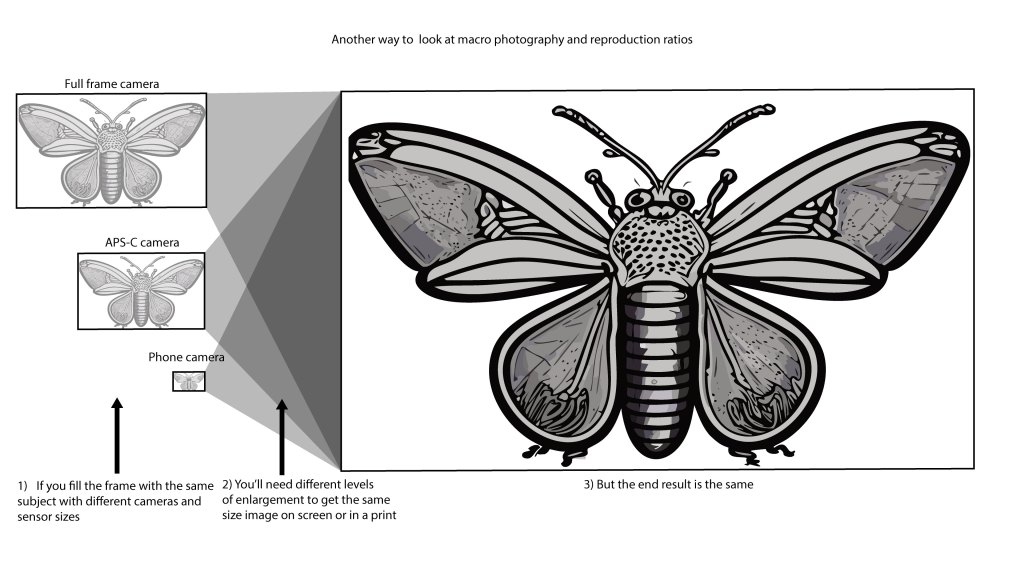

How print and screen sizes affect the magnification

Of course, nobody ever looks at a photo at the actual size on the sensor. Images are enlarged by varying degrees for different screen or website sizes, or to make photographic prints. It’s all very well saying that an object is captured at ‘life size’ or at a 1:1 reproduction ratio by the lens, but when you blow it up to fill the screen or make a print, you’re applying a big magnification. Our insect might have been reproduced ‘life size’ on the sensor by the lens, but when we view the image it’s going to be massive.

That’s one reason why the idea of reproduction ratios and this 1:1 ratio for ‘true’ macro photography doesn’t tell you anything about how big objects will look when you display the photo. There’s another reason.

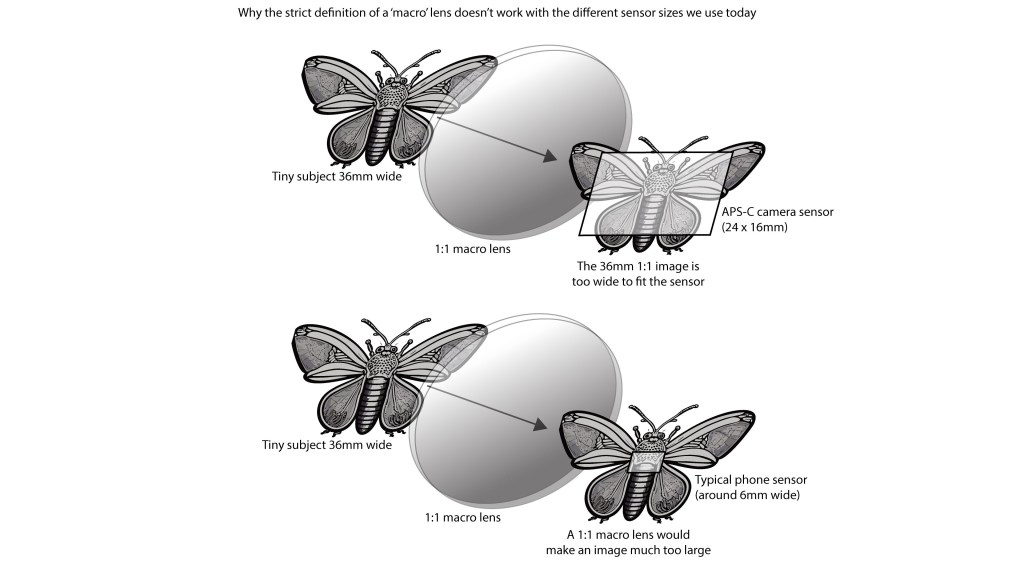

The sensor size messes with reproduction ratios too

This old-school definition of macro photography is very good at defining exactly how close you have to be and the kind of lens you need to get this 1:1 reproduction ratio. The trouble is, while it made sense when photographers were mostly shooting on a single format, mainly 35mm film or perhaps medium format, this definition becomes next to useless in the modern digital age.

Why? Because today’s smartphones and cameras use a huge variety of sensor sizes, mostly much smaller than the old 35mm film/full frame format.

So if you apply the same 1:1 macro rule to an APS-C camera, where the sensor is around 24mm wide, our 36mm long insect won’t fit in the frame. That 1:1 ratio doesn’t help us much here. In fact, you’ll have to move back a little to get the whole insect in the shot, so you will end up with exactly the same photograph, but a macro expert will argue it’s no longer ‘macro’ photography.

Mad, isn’t it? It would be much better to talk about macro photography in terms of the size of the subject or your field of view. Macro experts are right to insist the word relates to this specific 1:1 ‘life size’ reproduction ratio, but would have to concede that filling the frame with the same subject counts as the same effective magnification in the end.

So you can get into all sorts of arguments about whether phones or point and shoot cameras are capable of ‘macro’ photography, but if they can all fill the frame with the same subject, it seems pretty academic.

There’s still some woolly marketing hype to dodge, though. Some cameras and lenses have ‘macro’ modes that don’t focus close enough for small objects, just a bit closer than normal. There is a lot of vagueness about where ‘close-up’ photography ends and ‘macro’ photography begins.

So are macro lenses better than smartphone macro modes?

In a lot of ways, yes. Even if your smartphone can focus close enough to fill the frame with the same subject as a full frame camera with a macro lens, the results are going to look different. You can take ‘macro’ shots with a smartphone, for sure, but they may not look great.

First, the image quality won’t be as good. The sensor in a smartphone just doesn’t have the detail rendition or clarity of a proper camera sensor. A lot of the time it might not show, but if you make a big print or do any kind of image editing, you’ll certainly see a difference.

Second, smartphones use a lot of computational processing behind the scenes so that what you get might not be what you think. My iPhone has a ‘macro’ mode where it switches from the main camera to the ultra-wide camera when you move really close to a subject – that’s because ultra-wide cameras on phones adapt better to focusing this close (as long as your phone’s ultra-wide-angle camera has auto-focus).

My iPhone does try to keep this swapover subtle, but you can still see it happening. It’s actually doing something rather clever, keeping the main subject the same size as it swaps lenses, by cropping the image – but you can see the background ‘shrink’ to reflect the wide-angle view. So as well as cropping into the image, there’s also some clever computational processing going on here, because if I just use the ultra-wide lens and move in closer, my subject looks more distorted and I get a different effect.

Your smartphone may be doing a lot of behind-the-scenes juggling to capture ‘macro’ shots, and there are other ways that proper cameras and macro lenses can deliver better results, quite apart from having bigger sensors and more megapixels.

Apple introduced macro photography features with the iPhone 13 Pro, with the ultra-wide angle camera featuring auto-focus. If your camera has an ultra-wide-angle camera with auto-focus, check to see if you can shoot macro photos with it. Alternatively, if you have one of the latest Xiaomi, Vivo/iQOO, OnePlus, and other flagship Android phones, then you may be able to use the telephoto lens for macro photography. This will give you results that look a lot more similar to the results you’d get from using a camera with a macro lens.

One of the chief advantages is that you can shoot small subjects from further away with longer focal length lenses. This makes it easier to photograph timid insects, for example, and it means you’re less likely to cast a shadow over your subject with the camera.

Even more importantly, though, you get a much flatter and more natural perspective. You don’t get the same kind of close-up distortion you get from shooting right up close. Better still, a longer focal length lens doesn’t pull in so much of the background, so it’s easier to place your subject against a complementary and non-distracting backdrop.

Phones do have advantages for macro shots

First, shooting ‘macro’ shots with a phone is easy. You don’t need any special equipment or time-consuming setups. If you can get close enough and hold your phone steady for a second, you’ve got your shot.

You don’t get the same depth of field issues as you do with proper cameras and macro lenses, either. This is one of the technical headaches for serious macro photographers – when you use cameras with larger sensors, you’re also shooting with longer focal lengths, and this combination of a long focal length and ultra-close focus distances makes for razor-thin depth of field – even if you stop the lens right down to its minimum aperture.

Serious macro photographers will often use ‘focus stacking’ tools to take a whole series of shots at microscopically different focus settings so that they can be merged either in the camera or later in software to blend the sharpest parts in each. Often this is the only way to get all of the subject sharp.

Smartphones may be limited for macro work, both for image quality, perspective and background control, and may not reach the same levels of magnification as proper macro lenses, but they are quick and effective and dodge many of the technical demands of serious macro gear.

And while a photo expert might claim quite correctly that this is not proper macro photography, if you can still end up with a shot with a similar effective magnification, it seems like a theoretical argument not a practical one.

Smartphone ultra-wide macro vs telephoto periscope lens macro:

On the left is a macro photo taken with the Google Pixel 9 Pro XL, which uses the ultra-wide-angle camera and crops into the image to give a macro close up image. At first glance, the image looks good, with a great depth-of-field, and more of the photo in focus. However, when looking for detail, and viewed at 100%, the image is pixelated and fine detail is lacking.

In comparison the Vivo X100 Pro uses the 4.3x telephoto periscope camera, with close focus, and gives much more impressive pixel level detail. The background is blurred, and the image looks much more like an image you’d take with a real macro lens. The only issue is that the colour saturation is perhaps a little bit too high. JW.

So if you’re happy with the macro shots from your smartphone, keep taking them! But if you decide to move up to a camera and macro lens combo, you can expect better quality results for sure, and maybe higher magnifications, but it’s a pretty steep learning curve too.

Related reading

- Best smartphones for macro photography

- Best macro lens for mirrorless and DSLRs

- How to take great macro photos on a smartphone

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.