Damien Demolder talks to street photographer Alan Schaller, who says finding a strong, recognisable style that works for a wide range of subjects and places is critical for getting noticed and for keeping it fresh

It’s pretty important for those who use their cameras to pay their bills to have a signature of some sort, something recognisable that marks them out from the crowd, and which makes them the first person photography-buyers think of when they visualise their next campaign.

Some photographers get known for the types of things they photograph, like cars, people, dogs or products, while others use a specific eye-catching technique that they practice, perfect and roll out again and again until we all take notice. A strong signature gets you noticed more quickly as what you do – your ‘thing’ – is much more obvious, but after a while of sticking to that ‘thing’ some photographers find themselves down an alleyway they can’t escape from without totally re-inventing themselves.

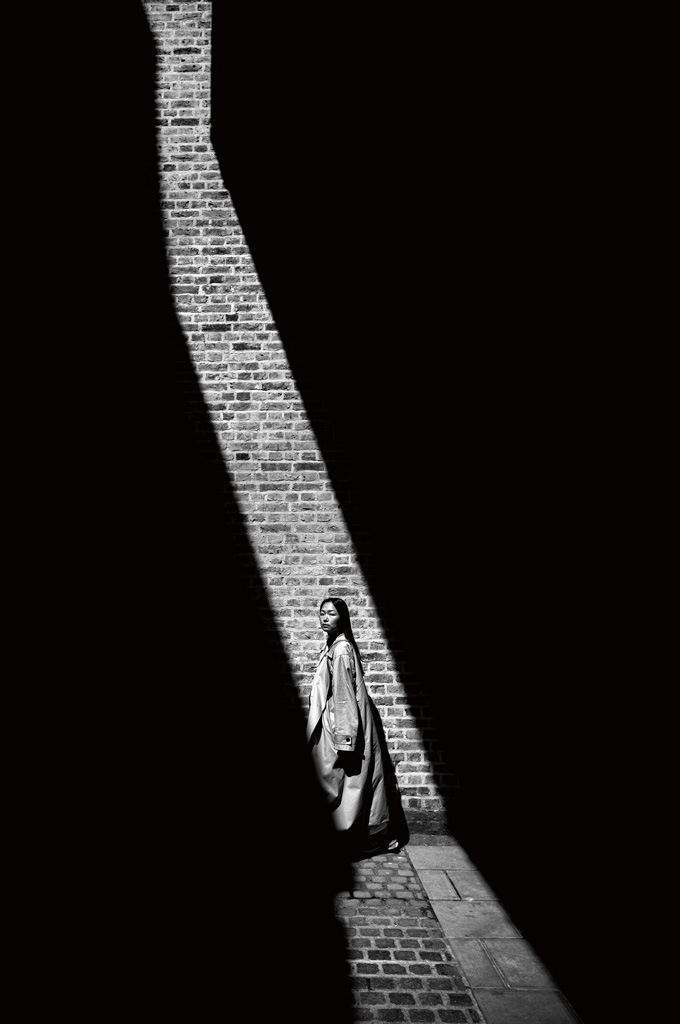

London. Leica M10 Monochrom, 24mm, 1/4000sec at f/9.5, ISO 160. Photo: Alan Schaller

How to create a distinctive style in your photography

The trick, says street photographer Alan Schaller, is to have a strong style that works perfectly with the genre you are known for, but which also translates into a wider range of subject types while remaining firmly identifiable as your own.

‘I like a really strong, high-contrast, look,’ says Alan. ‘I want my work to look like my work, and I want people to be able to recognise it even when it doesn’t have loads of black in it. I think I’ve managed to pull that off, and as long as I don’t stray too far with my subject content my pictures still look like mine. I just have some principles I’ll stick to, an editing style and my lens choice – which all comes together to create that signature look. Having a strong, identifiable look is more important than ever now. It takes a while to get people to understand what that look is, and what you’re about.

London. Leica M11 Monochrom, 24mm, 1/1250sec at f/9.5, ISO 125. Photo: Alan Schaller

‘When we think of famous photographers we can picture their work in our head, and that’s something I’ve strived for and worked to figure out, more than I concentrated on what shutter speed I needed for certain types of shot. Technical stuff is important of course, but there are bigger things that need our attention.

My advice is to try to focus on an aspect of photography you find the most interesting and that works well for you, rather than trying to level up the things you aren’t good at. Also try to keep the work you show consistent. Consistency and repetition are often misunderstood for one another. Repeating the same shot is not the same as being consistent. That’s something I try to think about a lot, as I don’t want to just tread the same ground all the time.

Photo: Alan Schaller

‘You can avoid repetition by not pressing the button when you see that you are just shooting the same thing again, and often by not going back to the same spot. I’m very lucky that now I get to travel a lot, so when I approach every place and every scene in the same way I can let the place dictate the variety. Whether I’m in Istanbul, Tokyo or in the English countryside I will try to use the same ideas when it comes to lens choice, composition and metering. I have a look but I’ll let the environment dictate the difference, and when you go to a new place you’ll probably get a new shot.

Photo: Alan Schaller

‘If though you go to a new place and try a new technique, like shooting in colour or something, that’s just going to be confusing. Wherever I am, I’m shooting people or architecture, if I shoot in black & white with a 24mm lens, using interesting light, it will probably look like one of my pictures. I’ve shot in the mountains, on ski slopes and turtles underwater in the Caribbean recently, and they all look like my pictures. They are completely different from my street photography, but the style is the same.’

The Gang. Leica M Monochrom (Typ 246), 24mm, 1/750sec at f/2.8, ISO 320. Photo: Alan Schaller

Street with no name

‘I’m very hesitant to say “yes, I’m a street photographer” because that can get me in all sorts of trouble with the street photography community who can be quite militant. I do shoot traditional street photography, but I do other things as well, so I try to just label myself as a “photographer”. I did also co-found Street Photography International so, you know, I’m very passionate about street photography and I love it – and most of my work historically has been street photography.

‘There are lots of definitions of street photography depending on who you speak to. My definition is, I suppose, candid images or moments that reflect human life that are taken by a photographer. That can mean some pictures might contain just pure aesthetics, so it might just be some shapes or some light, or some coincidence. There’s so much more to it than just a random person on the street.’

Something I find interesting is the idea of what candid means. If you’re taking a picture of someone and they notice you, does that count? Or does it have to be that the subject is totally unaware of your existence in order for it to be classified as a candid?

Barbados. Leica M10 Monochrom, 24mm, 1/750sec at f/6.8, ISO 160. Photo: Alan Schaller

‘To be honest, I’m not really sure how I would define street photography. I just think it’s capturing human life around you. That can mean architecture – which is a product of people – but street pictures should say something or be beautiful. They have to have a purpose. I think a lot of people, and myself included when I was beginning, think street photography means people on streets, but street photography can extend to well beyond the street. It can be on beaches, and I’ve shot candid pictures on airfields when I’ve been doing shoots.

‘I’m very good friends with the photographer Matt Stewart. He’s now doing a lot of pictures of buildings and colour coincidences that he sees on the street, and the pictures largely have no people in them. He’s very much a street photographer and sources all of his images on the street, so I see that as street photography too.

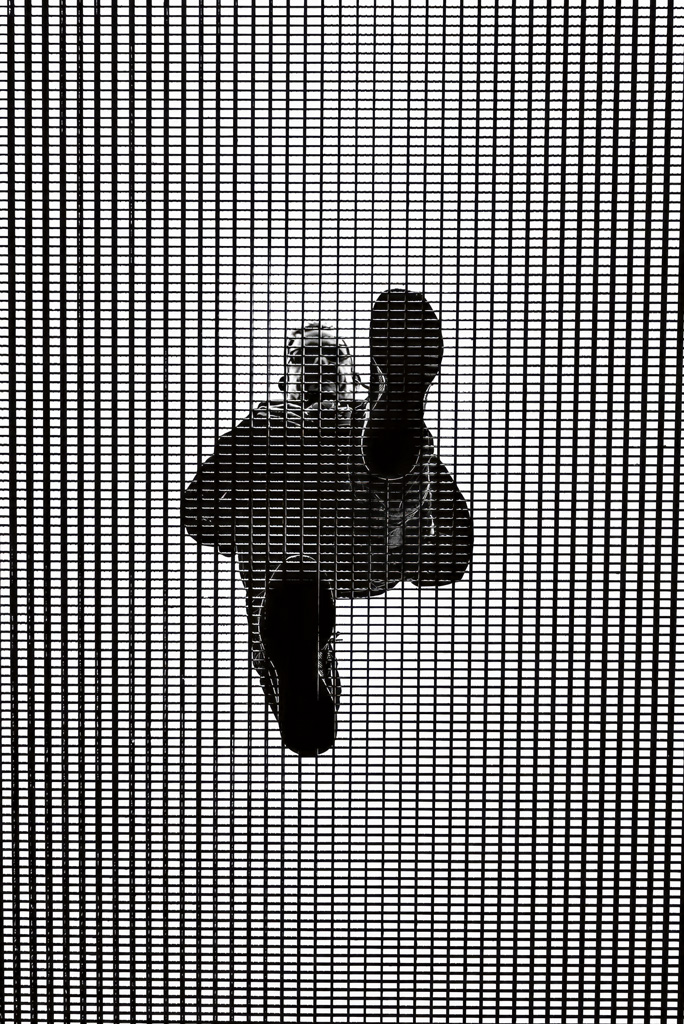

Heathrow Airport. Leica M Monochrom (Typ 246), 50mm, 1/2000sec at f/1.7, ISO 320. Photo: Alan Schaller

‘The answer to the question “what is street photography?” I suppose depends on who you’re talking to. My photography certainly started in traditional candid pictures of people around London, but what I do now is often looking for scenes that allow me to extract a lot of contrast and a surrealist, or certainly abstract, feel.

I’m almost trying to make somewhere look completely different from how it looks in real life. I don’t know what that’s called – I just enjoy making images. Obviously I practise traditional street photography most of the time but if there’s no opportunity to get a shot candidly I’ll ask a friend or my partner to step in, if they are with me, to make a picture look nice. I even use myself if I have to.

Photo: Alan Schaller

‘There’s a shot I did in Lisbon where there was just no one around. It was the most beautiful old cobbled part of the city and the light was perfect. I waited for 20 minutes and the light was going so I popped the camera in someone’s flowerbox on a window sill and put it on a 12-second timer so I could get into the shot. Is that street photography? I don’t know, and I’m not interested really.

I like creating images and if I see something, I feel I should be able to take it, but you get a lot of people who are very robustly against that sort of idea. You know, if you’re a street photographer then everything should be candid, and that’s it. Robert Doisneau is a classic example. He made so many amazing street photographs but his most famous picture, ‘Le Baiser de L’hôtel de Ville’ (The Kiss by the City Hall) was posed – and so everyone discredits him. It’s a joke.’

North bank of the Thames, London. Leica M10 Monochrom, 24mm, 1/4000sec at f/6.8, ISO 200. Photo: Alan Schaller

Street photography or not?

‘Unfortunately I see a lot of negativity in the street photography world. I don’t see so much among portrait photographers and other genres. That’s not to say there isn’t positivity – there’s a hell of a lot of that as well. It’s just it seems to be a genre that’s extremely rules-based according to some. I just don’t see the point in that. You should be honest about how you’ve made your image, and as long as you are I think it’s fine.

It doesn’t really matter if a picture is “street photography” or “street portraiture”. If you are entering a photo contest and its rules state they are only accepting candid photography and then you enter a picture that isn’t candid and you say it was, that’s wrong. But is it wrong to have taken it in the first place?

Photo: Alan Schaller

‘No. It’s hard enough to make a good image without limiting yourself like that. I actually don’t stop people who I don’t know, but if I’m with someone who I could use in an image, and there’s no other way around it, then I will. To be honest sometimes it’s better to do that than it is to take a candid picture because you can control it more. That’s me going on the record.

I know there’ll be people who’ll say, look, he stages everything. I don’t – I can candidly shoot toe-to-toe with anyone. There are a lot of people who focus on this stuff and it’s a shame because we’re the street photography community and the photo community in general should stick together. There are a lot of other issues in the world that are more important and worrying that they could focus their energies on.

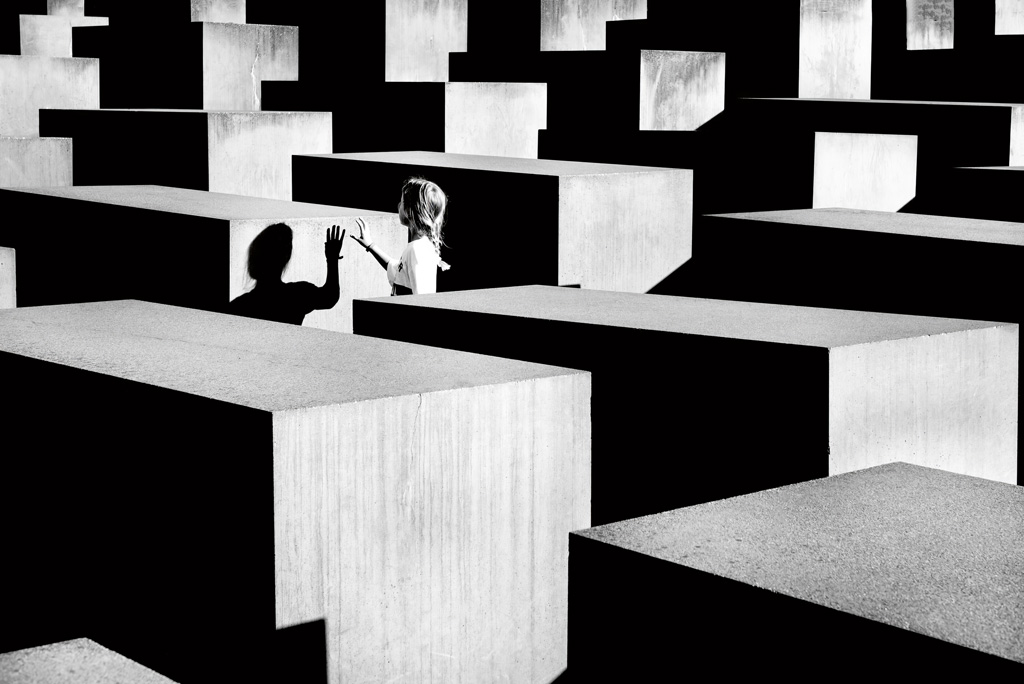

Berlin. Leica M Monochrom (Typ 246), 50mm, 1/1000sec at f/8, ISO 640. Photo: Alan Schaller

‘I also want people to understand my process and that all street photographers have taken other kinds of shots. People need to realise that’s okay so they can feel free to shoot that way too. I teach workshops and people literally say, “Oh, I wouldn’t take a picture like that because it breaks rules”. It’s just ridiculous. I don’t pat myself on the back for getting a shot candidly. I don’t think it’s going to get me a nicer apartment.’

Creating a recogniseable style: Atmospheric influence

It would be reasonable to assume that Alan’s influences come from other street and documentary photographers, but he says it isn’t the subject matter that he sees in other photographer’s work so much as the atmosphere they create and the means by which they do it.

Photo: Alan Schaller

‘The photographer who influenced me the most is Ansel Adams and he didn’t traditionally photograph people. I loved that he put filters over his lens to make the granite rock faces look really dark. He didn’t invent using filters for black & white, but he made it popular, and his images almost gave me permission to present the world in a way that our eyes don’t really see it.

He gave me the idea that perhaps things need to be exaggerated in order to convey an idea, and to hammer it home. I really appreciated that, and the realisation created a bit of a turning point in my work. I started to edit my work differently and to shoot and meter in a different way. I experimented with filters too, though I don’t use them any more, but reading about his ideas and seeing his prints had a bigger impact on me than anything else.

Saigon, Vietnam. Leica M Monochrom (Typ 246), 1/30sec at f/11, ISO 6400. Photo: Alan Schaller

‘I saw some of his prints when I first started shooting and I thought ‘Wow, that’s what a black & white print should look like.’ I was so far from that point and realised I had a lot to learn. I still feel the more you know the more you’ll discover different photographers and think “I’ll try a little bit of that and experiment with that”. It’s wonderful, and part of the process that helps photographers to develop their style. Everyone will follow different people and think in different ways, which makes interesting combinations. Now of course a lot of people are emulating what I do, especially on Instagram, and that’s great as well.

Photo: Alan Schaller

‘Some people try to say it was all their idea, which is annoying, but the best thing is getting a message from someone saying “Oh, I saw your photography and it made me really want to try it more seriously’ or “I tried black & white”, and that’s cool because I was in that position. I adore Bill Brandt too – and he was another big influence on me. I saw one of his portraits – the one with the legs taken in Belgravia somewhere – and that really influenced me. The picture abstracts and distorts reality. He was using a very wide lens, something like a 15mm, and I don’t think anyone had done that in the ’50s before.’

Millennium Bridge, London. Leica M Monochrom (Typ 246), 50mm, 1/1500sec at f/3.4, ISO 320. Photo: Alan Schaller

What kit does Alan Schaller use?

‘When I started taking pictures I had a Canon EOS 70D, but I rapidly realised it wasn’t getting me what I wanted. For me it was like using a chainsaw to nail-in a hammer. I’m sure it’s good for other things, but I didn’t get on with it. Then I tried out a Leica Monochrom rangefinder. I was a musician at the time and had just got a mortgage, so I didn’t really have the money, but I bought it anyway. My dad said, “How much was that thing?” and I told him, “It cost 11 grand with the lens, and it can’t even shoot in colour.”

Photo: Alan Schaller

‘I used just the 50mm for about a year until I realised I needed something wider as I was running out of space on the Underground. I had my back against the wall all the time trying to get everything in. That’s a good way to decide to buy a new lens – when you discover that you need it. I wasn’t going to buy a 135mm just because Don McCullin used one.

That focal length worked for him, but he was trying not to get shot in war zones and I was trying to fit more in on trains. I ended up buying a 35mm which I used for my first ever commission, which was in Hong Kong for the South China Morning Post. I quickly realised it wasn’t wide enough, so I got a 21mm which seemed a step too far. I got a 28mm but that seemed too close to the 35mm, so I tried a 24mm and fell in love with it instantly. It aligned with my brain and we just clicked, and now the majority of my work is done with either that 24mm or the 50mm.

London Underground. Leica M Monochrom (Typ 246), 50mm, 1/250sec at f/1.4, ISO 320. Photo: Alan Schaller

‘I’m a Leica ambassador, but I can say genuinely that I love the M11 Monochrom. It has a better dynamic range and is more sensitive to light so produces cleaner images at high ISO settings than regular sensors, and the detail it records gets a bit more out of the lenses. One of the most important aspects though is that you can’t shoot in colour, so you stop looking at colour.

With a film body you can still be tempted to whack in a roll of Portra 400, but with the Monochrom it’s a statement to your artistic self – and not only a bank statement – that you will work solely in black & white. You can stop being distracted by colours, and begin to notice the structure of things, seeing shapes and lines.

Photo: Alan Schaller

‘Of course you can use any camera to shoot in black & white, but none has the look of the Monochrom. I’m very particular about the way my images look, and I don’t want to spend hours getting my greys right. The Monochrom doesn’t have my look built-in, but it makes getting it much easier.

Of course, there’s a lot more that goes into my pictures than just the equipment – it’s about how you choose to shoot what you shoot and then how you post-process, but I would say for black & white photographers you would be hard pushed to get a better head start on your work than using the Monochrom.

Photo: Alan Schaller

‘We are in a golden age of cameras though, and people ask me whether the Fujifilm X100 is good enough for street photography. It’s leaps and bounds beyond what Henri Cartier-Bresson had to use, so of course it is. I think though that if you have £3,000 to spend, you are better off using it for a trip away somewhere to take pictures with the kit that you have. Being abroad will inspire you more, you’ll learn more about life and get to understand the world better – and you’ll get some great pictures that will show off what you can do.’

London. Leica M Monochrom (Typ 246), 50mm, 1/30sec at f/16, ISO 125. Photo: Alan Schaller

Refine your style by shooting everyday

‘I shoot every day,’ says Alan. ‘Whether it’s four hours or four minutes, I’ll try to get a bit in. By “shooting”, I mean walking around looking for a shot. Sometimes I don’t take any if I’m not feeling it, but I certainly try every day. I’ve been doing this for seven years now, and I never have a day off. When I’m out looking for shots new ideas come to me, and it helps me to develop and to learn new things. It’s also the only form of fitness I do – I’m not a gym guy – and most days I do an average of 15km.

I got a headset with a really good microphone for my phone so I can do meetings while I walk around. If I spot something I can just shoot it, as I don’t have to think so hard about it any more. In my earlier days taking a picture required every fibre of my being to be straining itself, but with practice it becomes a natural process.

Photo: Alan Schaller

‘I’m still very much exploring and enjoying the way I work at the moment and coming up with new ideas. It’s seven years since I picked up a camera so I feel like I’m still very much trying out things, but one of the reasons I got a Leica MP film camera recently was to see if that would inspire some different stuff. There are pressures, when you have a strong style, to keep delivering what your following expects, and if you’re not feeling it for a while that can become stressful.

Some people might feel pressured to just shoot the same thing again and again, but I see that pressure as a positive and a driving force. It makes me get up off my arse to get out there, to shoot, to get engaged with the world. Maybe if we have this conversation again in another seven years I’ll think differently about it.

London. Leica M Monochrom (Typ 246), 24mm, 1/1000sec at f/4, ISO 320. Photo: Alan Schaller

‘At the moment though shooting film is making a nice difference, and I’ve produced some new images in the places I’ve been walking for years. It’s giving me a lift and making me see things differently. I’ve tried a few films, but have settled on Ilford Delta 400 as it gives me the look I like and I can match the results to those I get with the Monochrom.

‘I will also try out a different focal length if I get bored. Shooting with a 90mm is just completely bonkers for me as I’m so used to the 24mm, but it will keep me thinking and force me to look for new perspectives. I got a 280mm recently with a 2x extender which I also used to shoot some street. It was really cool and I got some stuff I wouldn’t have otherwise. I love experimenting and messing around with these photographic tools that help me to express ideas in different ways.’

Photo: Alan Schaller

Creating a recogniseable style: what about post-production?

‘Most of the work that goes into my pictures comes at the shooting stage. It’s about metering for the highlights and allowing dark areas to go dark, but what I do in Lightroom is also very important to creating the look that you see. I work on each image individually with a bespoke set of adjustments that suits that specific shot. I never use presets as how the hell can they match what each image needs?

‘I’m self-taught in Lightroom and didn’t watch YouTube videos on how to do things. I might have saved myself some time perhaps, but I think developing my own methods is one of the things that make my pictures mine. I spoke to a master printer recently and it turns out what he does in the darkroom is very similar to how I work on my images digitally, so it was nice to know that after figuring things out for myself we’ve come to the same conclusions.’

Photo: Alan Schaller

Why it works

Alan Schaller is a street photographer, right? But here’s a picture taken on the ski-slopes that is still very much an Alan Schaller image. How does that work?

Photo: Alan Schaller

We might think of the ski slopes and the streets of London as being very different environments, but the key element of people going about their business in the world is the same in both situations. The key though to this image fitting in with the rest of Alan’s images is the strong style – high contrast, deep, deep shadows and silhouetted characters shot in black & white, with a wideangle lens. Alan has also used a dramatically graphic composition, with strong diagonal lines heading into the corner of the frame, and a spectacular sky to produce an image that is much more about the atmosphere of the moment than the people in it.

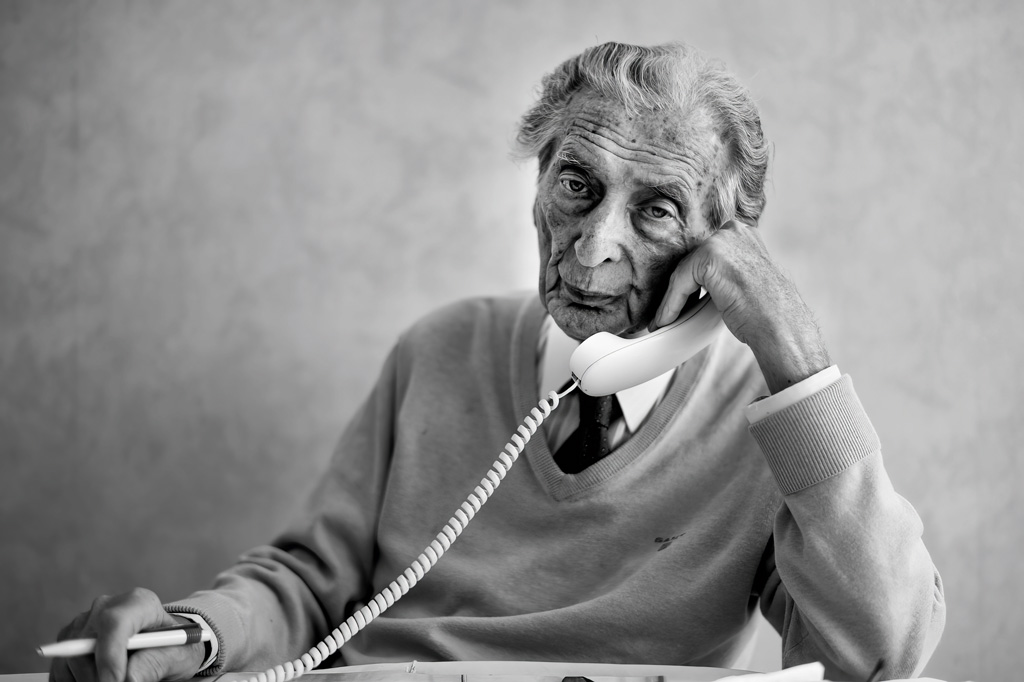

Portraits in street style

‘I do quite a lot of portraiture now, and when I do I maintain the same sort of style that I use when shooting in the street. This is a picture of my grandfather that I took when I was quite new to photography. I’d gone to have lunch with him but he was on hold to John Lewis about his TV and wouldn’t speak to me while he waited. He had an extraordinary face and an intense expression, so while I waited for him I popped my camera on the table and just angled it up at him. It’s one of the best pictures I’ve taken, and it was through photographing him over the years that I got to know him a bit better.

Photo: Alan Schaller

‘I’m not one of those portrait photographers who shoots 500 pictures in a session – there’s just no need. I shot a well-known actor a while ago, and took four pictures. He couldn’t quite believe it. He liked all four pictures though – and he only needed one, so he had more than he came for. I’d rather use the time to get to know the person first, rather than aimlessly shooting loads of pictures that will never be used. ‘When I shoot portraits I do so in my own style, the same style as I shoot street. And I often use a wide-angle too if I want a dramatic effect.’

Alan Schaller’s top tips for creating your own style in photography

1. Find what you are good at and stick to it. You want to improve, of course, but there’s no point hammering away at a style or subject matter that you don’t love and which isn’t working for you. Spend your time doing the things you are good at, and get better at them.

2. Don’t buy kit because someone else likes it. Discover what works for you and use that. We all have different needs and ways of seeing, so investigate cameras and lenses until you find the right set-up and then you won’t have to think about kit very often.

3. Shoot as often as you can, and have a camera with you all the time. You can’t learn and improve without taking pictures, so the more you do it and the more effort you put into getting better, the quicker it will happen.

4. Look at other photographers’ work and be inspired by it. Don’t copy it, but appreciate their ideas and methods and see how those things might help your own work. It might be the way someone else uses tones, exposes, or composes their pictures, but look and see what you can learn.

5. Don’t feel limited by the ‘rules’ of street photography. They are often good for guidance, but never miss a chance to take a good picture just because someone else says all street pictures have to be candid. Do your own thing, and concentrate on making the pictures you like.

Alan Schaller is a London-based photographer who specialises in black & white photography. His work is often abstract and incorporates elements of surrealism, geometry, high contrast and the realities and diversities of human life. He co-founded the Street Photography International Collective (SPi). It was set up to promote the best work in the genre, and to give a platform to talented yet unrepresented photographers.

To see more of Alan’s work visit his website. Alan’s first book, Metropolis, will be published by teNeues and is due for release in September priced £75.

Related content:

- The law around street photography

- How to use smartphones for street photography

- How to be street smart as a photographer

- How to capture moody monochrome landscapes

Have street photographs you want to share with us? Why not enter them into our street category of Amateur Photographer of the Year.

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.