Personal style and keeping it simple are key ingredients to strikingly minimalist architectural images. Benedict Brain talks to two photographers to find out more.

Modaser

Based in the Netherlands, Modaser studied political science at Leiden University. His interest in photography started in 2010 with his Instagram account @meau. In 2018 he started using the account actively for architectural photography adopting a politically inspired minimalist approach.

For Dutch photographer Modaser, it was a trip to Russia in 2011 that sparked an interest in photographing architecture. Soviet architecture, to be specific. ‘I mostly like to shoot architecture in Eastern Europe and the post-Soviet republics,’ explains Modaser.

However, it’s not just the buildings that interest him, it’s also the relationship between former Soviet Union architecture and politics, another of his keen interests. ‘You can tell a lot about the period in which a building was constructed by reading its architectural style,’ he explains.

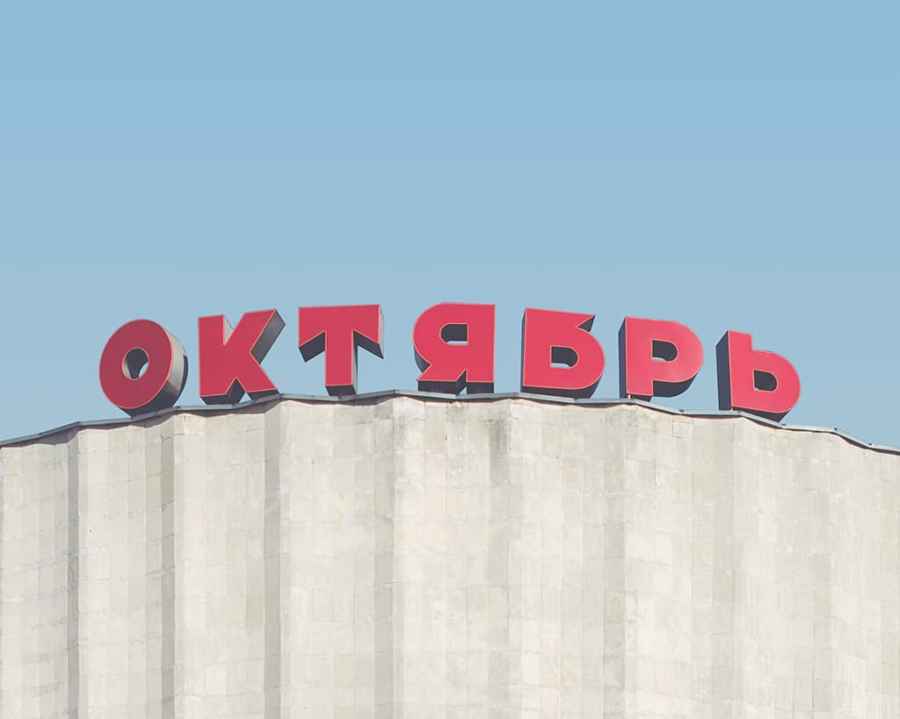

Cinema Oktyabr, Minsk, Belarus. Canon EOS 550D, 17-50mm, 1/320sec at f/7.1, ISO 100

He continues, ‘For example, the euphoria about a “new Soviet society” that existed before and after the Second World War can also found in the socialist classicism or Stalinist style of that era. Many of the buildings in this style were quite impressive and were extensively decorated with a lot of ornaments.

After Stalin’s death, Khrushchev came to power and he ordered an end to “architectural excesses”. ‘He needed to solve the housing problem in the USSR and saw the use of concrete and prefab housing as the solution. After Khrushchev there was Brezhnev, and he too left his mark on Soviet architecture. And so, one can easily distinguish between a “Stalinka”, “Khrushevka” and a “Brezhnevka”.’

Courtyard of Schlesische Str 30, Berlin, Germany

Canon EOS 70D, 17-50mm, 1/250sec at f/6.3, ISO 200

Modaser uses minimalism as a tool to isolate his subject, the building, or to focus attention on the architectural style. ‘The popular opinion about Soviet architecture is that it’s grey and boring,’ observes Modaser. ‘Nowadays it doesn’t look so good any more because the buildings and their surroundings are not taken care of and the people living in these buildings make alterations to the exterior that deviate from the original design.

A good example of the latter would be that a lot of people in post-Soviet countries chose to close up the balcony of their apartment. They did it with their own design in mind and with different materials. The result is that it looks horrible. That’s why I try to clean up a building in post processing in order to show a bit more of the original design. And when I isolate the building, I can put more emphasis on this design.’

Residential building on Bul Mira, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia. Canon EOS 70D, 17-50mm, 1/500sec at f/5.6, ISO 100

There is a certain amount of pre-planning and Modaser uses maps to figure out what the best point of view is and how the light will fall on a building. However, he also loves to wander around and shoot whatever he comes across. ‘If I see an interesting building, I pin the location down on my phone so that I can revisit it at a later time,’ he says.

‘In general, I like buildings with strong symmetry, clear use of geometric shapes and an interesting pattern because these work the best with my minimalist approach. I also like to shoot historical buildings that have their own story.’ The subtle colour palette and tonality in Modaser’s images are artfully controlled in post. ‘For the background, I use two hues of blue,’ explains Modaser, who continues, ‘A slightly more vibrant background makes the photo pop more without being too distracting. Also blue is a calming colour so it’s a good way to make the background disappear because I want to emphasise the architecture.

For the building itself, I try to make the colours pop a bit more but mostly it’s just some small tweaks together with my own LUT in Affinity Photo. I try to use mostly white, black, reds and yellows because I like the combination of these colours with a blue sky. For photos on Instagram, I add just a bit more contrast and saturation because I feel that it gets more attention on the platform that way.’

Pink house on Groenhazengracht, Leiden, Netherlands

Canon EOS 70D, 17-50mm, 1/640sec at f/4.5, ISO 100

Top tips

Find a topic or an aspect of architecture that you yourself find interesting instead of what you think others might find interesting and the creativity will flow more freely.

Practice, practice and practice. Try shooting the same image or scene multiple times over long periods of time to see how you can improve yourself and your photography.

Preparation is key. Try to visualise the photo, find out what time of the day works best for the photo you want to make and make sure you bring the correct gear.

Jeanette Hägglund

Jeanette is a Swedish photographer and artist based near Stockholm. She studied aesthetics, the philosophy of art and language, art, media, film and photography at universities in Sweden and abroad. She works as a commercial photographer and as an artist. See more at www.jeanettehagglund.se Instagram @etna_11.

Swedish-based pro photographer Jeanette Hägglund started taking photographs and making short films at the age of eight. She went on to study photography and then continued to explore the language of photography, experimenting with different films and developing techniques.

‘I try to think outside the box to play with different styles and to stretch the boundaries of photography,’ explains Jeanette, who continues, ‘at one early exhibition in my career, a photography teacher said that my work was not photography but art. So, “good” I said to myself, art-photography it is then!’

Jeanette doesn’t limit herself to photography though and is equally happy drawing and painting. However, the quick pace and immediacy of the photographic process suits the speed with which creative ideas come to her. As a professional photographer, Jeanette’s main subjects are architecture, branding and portraits. Her architectural photography is a mixture of commissioned work and personal practice.

Jeanette’s approach to photographing buildings is relatively straightforward. ‘I want to create my own style where I am concentrating on the essence of a building,’ she says. While there is a strong element of abstraction and minimalism in her architectural work Jeanette strives to capture and highlight a structure’s unique character.

‘I have always been interested in geometry and how it appears in architecture,’ she comments, and continues, ‘I think minimalism highlights what I want to capture. When I make an abstraction, I want to highlight the unique, in a kind of semantic way I’m interpreting the building.’

For Jeanette, the minimalist approach, the use of abstract light and colour all come together to form her unique style. ‘Colours, light, textures, tones and so on are all part of all the image,’ she remarks, and adds, ‘Colours are interesting and have a strong meaning and effect on us. I love colours, but I simply use what I have in front of me.’

Planning plays a vital role in her workflow. ‘I do a lot of research and check the orientation of the building so I know how and when the light will fall on it during the day,’ notes Jeanette. ‘I often have more than one building to shoot. It all depends, there is no typical procedure of which buildings. Depends on the work, or if it’s a project with a special subject.’

Unlike Modaser (see above) Jeanette never uses image editing software to alter her composition and the images are as she framed them in the camera at the point of capture. Many architecture photographers work in the early morning and in the evening, to take advantage of the magic hour, the blue hour and so on; Jeanette embraces this too but also works throughout the day to take advantage of the hard, harsh shadows on the midday light which can further enhance strong, graphic architectural shapes and lines.

If possible, Jeanette will return to a building many times to find her favourite light. ‘I’m always full of ideas and have a great imagination but I want to stay open for changes in my plan,’ she explains. ‘I want to let reality mix with my preconceived ideas, letting the architecture affect me at the same time and mixing it with my ideas. I see my work as interpretations.’

Jeanette works with tilt-shift lenses to correct verticals and keep lines straight. ‘I have many different lenses, depending on whether I’m capturing the whole, parts or making close-ups of a building.’ It’s perhaps surprising that despite the very formal approach to Jeanette’s style she rarely uses a tripod. She concludes, ‘I’m very stable and have my own technique to be as still as possible. Although I will use a tripod in a very low-light situation.’

Top tips

1 Have an idea of what kind of buildings you want to shoot and why you want to shoot them. Once you’ve developed a style, try to stay within it and look for buildings that fit into this mode of thinking.

2 Light is vital and it’s good to choose a day with the right light. If you can, return to a building multiple times over a long period of time to see how the light changes and affects the building in different conditions and from different angles and times of the day.

3 Look for lines and shapes, shadows, patterns, tones, textures and colours and make a note of how they interact with each other and try to capture the spirit of this.

Further reading

Take better architecture photos