Launched at MoMA 70 years ago, Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man remains photography’s most ambitious – and divisive – exhibition. But its surprising final home is a story in itself.

Earlier this year a friend of mine phoned in a bit of a fluster. He’d just seen a photography exhibition and claimed to have had a reaction not unlike seeing the Stanze of Raphael, reading the last pages of Joyce’s Ulysses, or listening to the second side of Joy Division’s Closer. To be fair he’s prone to poetic outbursts. I listened with caution. As he rattled through descriptions of grainy prints and unexpected juxtapositions, I felt my pulse quicken. He was describing The Family of Man.

I’ve owned the Family of Man book since my A Level photography days. First shown at MoMA in 1955, the exhibition comprises 503 photographs by 273 photographers from 68 countries. Nine versions of the show were created and toured to around 160 venues in 37 countries including Russia, Germany and Japan. It was seen by an estimated 10 million people. I never thought I’d see it.

Where is it? Not New York, Paris. Not even Bradford

Then came the real surprise. Where is it? Not New York, Paris. Not even Bradford. But Clervaux in Luxembourg, a land better known for castles and investment funds than photographic history. And yet, it made perfect sense—Edward Steichen, the exhibition’s creator, was Luxembourgian and had requested the exhibition be permanently installed there. A few emails exchanged with the Luxembourg Tourist Office and I found myself boarding a 65-minute Luxair flight from London City airport.

Clervaux Castle is a pristine affair nestled in the north of the country, like someone built it from a model village or inspired a World War II Hollywood film set – it may have, the opening engagement of the Battle of the Bulge took place here. In 1964, as Steichen wished, the US government donated the exhibition to Luxembourg. After a period of partial display and extensive restoration, the full exhibition was permanently installed at Clervaux Castle in 1994 – 21 years after Steichen died. In 2003, it was recognised by UNESCO as part of the Memory of the World register, and following further renovations, it reopened in 2013 in a purpose-built, climate-controlled space: 18–20°C, 40–50% humidity, and UV filters on the windows.

On arrival I was greeted by a parade of Patagonia jackets and kids in primary-coloured mud-splashed wellies. This version of the show was the third created, specially made for the European leg. It is composed of original silver gelatine prints on baryta-based paper mounted on wooden panels, which—if you’re interested in conservation—is about as sensible as using Pritt Stick on the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Each version was packed into around 26 crates totalling 1.5 tonnes

Each version was packed into around 26 crates totalling 1.5 tonnes – it took over a week to hang following a sheet of instructions. Many of the images bear the signs of their 70-year journey: smudges, cracks and scratches. It only adds to the charm. The exhibitions were only supposed to last one decade not seven.

The show is closed two months a year and two days a week, partly for preservation and partly, I suspect, to give the staff a breather. The collection has been reconstituted as an archaeological object. The reinstatement of the exhibition respects its historical chronology and the wish of its creator to communicate through images. This is not just a gallery—it’s an archive, a time capsule, and a temple to Steichen’s monumental ambition.

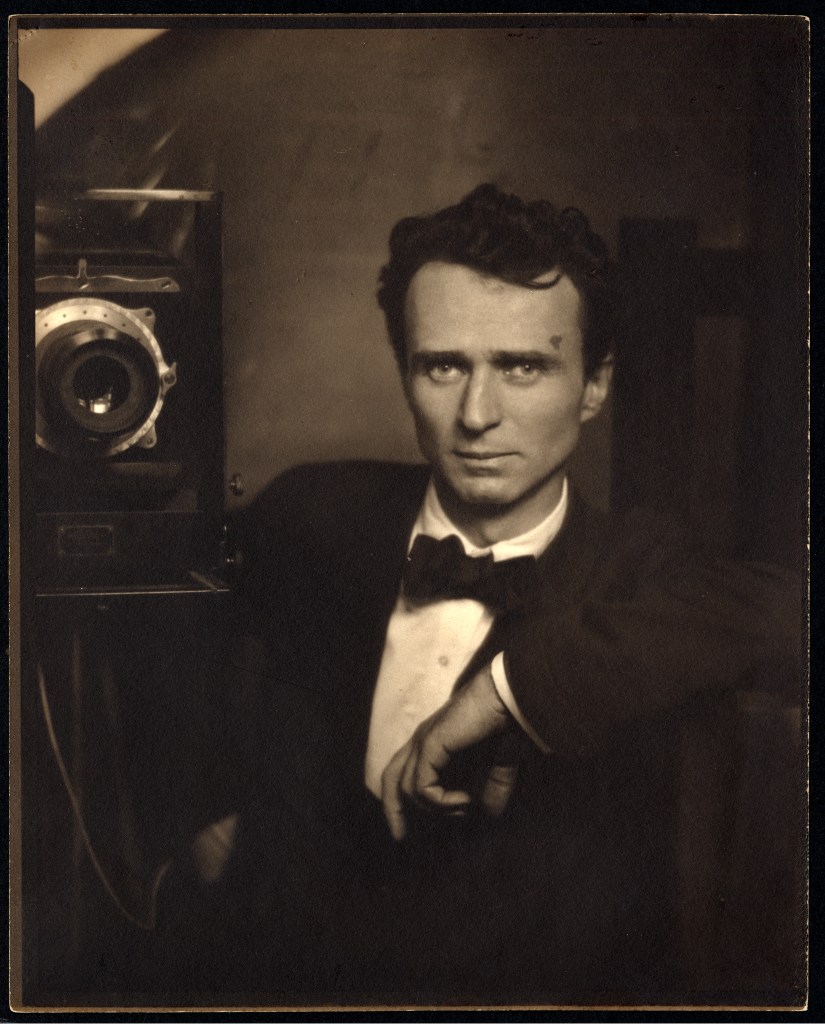

Born in 1879 in Bivange, Edward Steichen was many things: a pioneering photographer, a veteran of two World Wars, a curator, and a man who expected dog-like obedience from his staff. Influenced by a politically progressive mother and a suffragette sister, he believed in tolerance but practised ruthless editorial control.

Between 1951 and 1955, Steichen and his team waded through over two million photographs and looked at millions more. He worked from an office above a New York discotheque of questionable repute, occasionally sleeping fully clothed on piles of prints. No one fully understood his vision, but everyone wanted in.

Steichen had a mission: to create a universal visual language that transcended race, class and geography

In the foreword to the book he writes, ‘I believe The Family of Man exhibition… is the most ambitious and challenging project photography has ever attempted.’ For previous exhibitions Steichen had attempted to shock by exhibiting photographs showing the full horrors of what man can do to man. For this he took another approach.

The images selected—five of them Steichen’s own—were edited, cropped (yes-including Henri Cartier-Bresson’s), and sequenced with military precision. Some photographers grumbled (he’d made them sign away all rights), but Steichen had a mission: to create a universal visual language that transcended race, class and geography.

Steichen’s genius wasn’t just in image selection but in spatial choreography. The prints aren’t all at eye level—some are high, some low, some even overhead. There’s an almost musical rhythm to the layout. You don’t just look; you move, weave, crouch, bob.

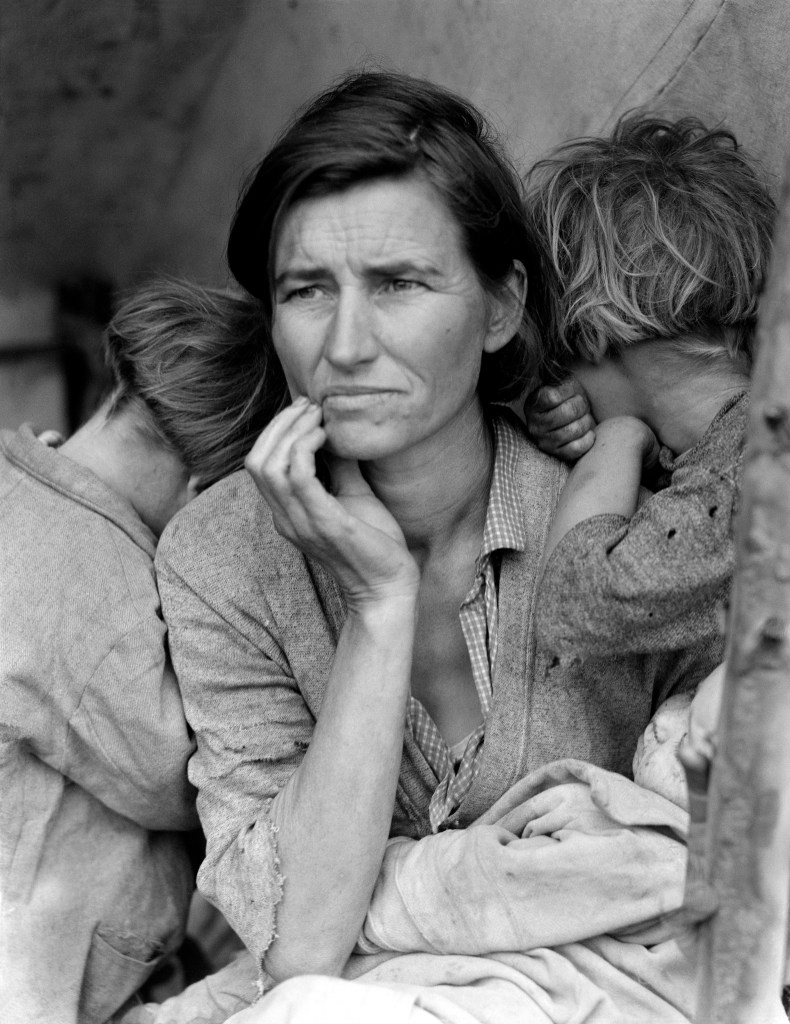

Humour crops up in delightful ways: a photograph by Ernst Haas of Albert Einstein seemingly searching for his glasses, is hung next to a child solving a simple maths problem while wearing thick specs. A strobe-lit ballerina by Gjon Mili spins not far from a formal studio portrait by Irving Penn. Technique is not the point—humanity is.

From birth to death, war to dance, the exhibition flows like life itself. A series of workers is hung like bricks in a wall. Japanese, Italian, and German families hang together like neighbours. Visitors are squeezed between two walls thick with images of death before being hit with a bang—a giant photo of a hydrogen bomb blast. At MoMA this was reportedly backlit with red light, just in case you weren’t feeling the apocalyptic stakes.

The exhibition is a roll call of photographic greats where surnames suffice – Eisenstadt, Brandt, Capa

But Steichen doesn’t leave you smouldering. The final photo, W. Eugene Smith’s The Walk to Paradise Garden, shows two children (Smith’s own) walking into a clearing. Smith had nearly lost the use of his hands in WWII. This image was among the first he took after dozens of surgeries. It’s not just hopeful—it’s defiant.

The exhibition is a roll call of photographic greats where surnames suffice – Eisenstadt, Brandt, Capa – others return zero search results on Google. Some images achieved fame because of the exhibition—like Henri Leighton’s 1954 photo of two boys, one Black and one white, walking arm-in-arm past shopfronts. Some were already famous—this was the golden age of photojournalism, with copies of weekly magazines Life and Picture Post selling in their millions.

Of course, not everything about The Family of Man has aged well. Critics Roland Barthes and Alan Sekula argued it was little more than Cold War propaganda—a vision of humanity scrubbed clean of politics and cultural difference.

Susan Sontag, in her seminal work On Photography, argues that its attempt to universalise human experience through photography is ultimately flawed. She contends that the exhibition simplifies complex human experiences and reduces them to sentimentalised clichés, thereby obscuring the social, political, and historical contexts that shape individual lives.

Comments in the visitors’ book range from profound to priceless

Steichen adapted the exhibition after launch – removing country credits (these appear in the book). An image of a lynching was taken out seen as an American not universal problem – MoMA visitors clustered around it, disrupting the exhibition’s intended flow. In Japan, images of Nagasaki were added then swiftly removed.

It’s also been accused of romanticising suffering and portraying Africans through a colonial lens. The intentions may have been noble, but the execution wasn’t always nuanced. Quotes from diverse communities are often vague—‘Sioux Indian’ rather than an individual’s name.

Despite its flaws, the show still speaks. My guide recounted a 12-year-old visitor who learned where babies come from after being convinced that a photo by Wayne F. Miller of his newborn son still attached by the umbilical cord—wasn’t a fake. It still has the power to provoke, to move, to teach. And sometimes, to scandalise. Modern visitors gasp at the full-frontal nudity. Comments in the visitors’ book range from profound to priceless:

An exhibition that changes life and viewing of the world. Such an honour to be here. Maya, 18 years, Poland.

WONDERFUL MESSAGE BY WONDERFUL PICTURES AND WORDS. KEEP FOREVER. Anonymous

Entry fee just €6

The curators used over 30 thematic groupings to help shape the exhibition’s narrative, although these aren’t always explicitly communicated to the public. Some are obvious, others more subtle. My personal favourite? The images of leisure. People drinking, dancing, swinging (not that kind). Photos that suggest not only that we’re all human—but that we’re also hilarious. I stayed an hour after the two-hour tour ended, drifting through the rooms, smiling and quietly marvelling.

The Family of Man tries to remind us what’s at stake—not through warning signs but through wonder. It’s reassuring to know that the greatest photo exhibition ever created is preserved in a castle, high on a hill in a little country with a big heart.

As Steichen put it: ‘The mission of photography is to explain man to man and each man to himself.

Even Ryanair flies to Luxembourg – what’s your excuse not to go?

The Family of Man exhibition at Clervaux Castle is open from Wednesday to Sunday, 12:00 to 18:00. March 1 to January 1. Entry fee €6

Dench flew Luxair to Luxembourg City and had an early night at Hotel Novotel Kirchberg. In Clervaux he stayed at the Hotel du Commerce dining at La Table de Clervaux devouring the cod fillet in balsamic vinegar broth with Luxembourg apple before utilising the country’s free public transport system to Vianden, where he bottled out of riding the chairlift but did make the most of the indoor swimming pool and sauna at Hotel Belle-Vue.

Check out our best UK photography exhibitions to see in 2025