World Press Photo has been a benchmark for powerful storytelling through photography. Now, on its 70th anniversary, a landmark exhibition turns the lens inward — asking not just what the pictures say about the world, but what they say about the way we choose to see it.

Familiar frame — new question

A woman’s face streaked with tears in the rubble of an earthquake. An exhausted soldier resting in a bunker. A plume of black smoke rising from a skyline, its ominous curl as recognisable as the sound of an air-raid siren.

We have all seen images like these — in newspapers, on websites, flickering across television screens. Many of them have been World Press Photo winners, elevated for their emotional immediacy, technical skill and storytelling power. They have lodged themselves in our collective visual memory, shaping not just how we remember events but how we picture the world itself.

But what happens when you revisit these images — and thousands like them — with a more critical eye? What patterns emerge? And what do they say about the narratives that have dominated global photojournalism for the past seven decades?

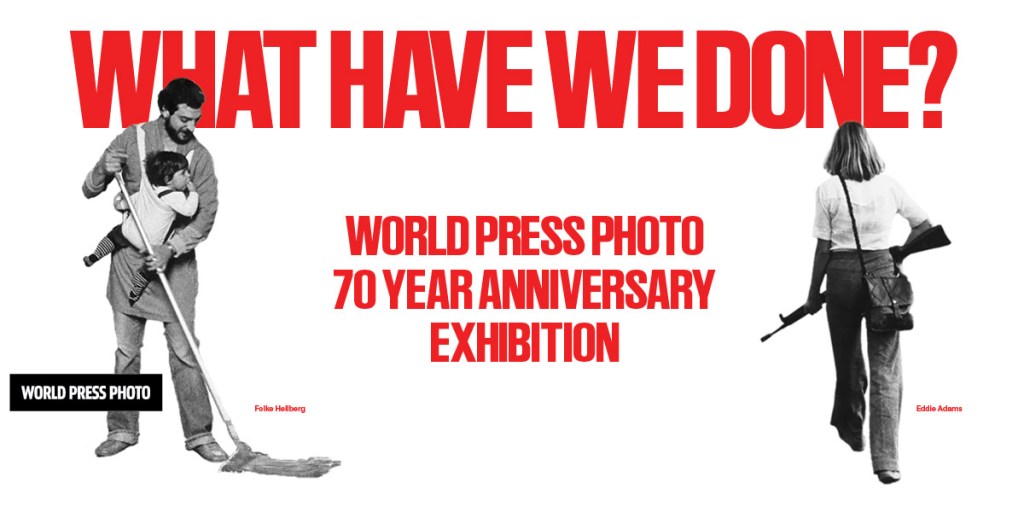

That’s the premise behind What Have We Done? Unpacking Seven Decades of World Press Photo, the flagship exhibition marking the organisation’s 70th anniversary. Curated by artist and photographer Cristina de Middel, it’s both a celebration and a reckoning.

From local contest to global benchmark

Founded in Amsterdam in 1955 by a small group of Dutch photographers, World Press Photo was originally a way to showcase work from beyond the Netherlands. Its first exhibition featured 42 photographers from 11 countries. Seven decades on, it has grown into one of the most prestigious competitions in photojournalism and documentary photography, with annual and thematic exhibitions reaching millions of people in scores of locations worldwide.

Beyond the annual awards, WPP has built educational programmes, grants and training to support visual storytellers. Its mission — to champion the power of photojournalism to deepen understanding, promote dialogue and inspire action — has remained constant, even as the media landscape has transformed beyond recognition.

Still, the 70th anniversary offers more than just a moment to look back at its proudest achievements. It’s also an opportunity to reflect on what its archive — a visual record of the world as seen through the lenses of thousands of photographers — says about the choices, assumptions and biases that have shaped global storytelling.

An exhibition as self-examination

Opening on 19 September 2025 at the Niemeyerfabriek in Groningen, in partnership with Dutch photography platform Noorderlicht, What Have We Done? will bring together more than 100 images from across the decades. A sister show will open almost simultaneously in Johannesburg, South Africa, at The Market Photo Workshop.

Cristina de Middel, a Magnum photographer known for work that playfully interrogates the line between fact and fiction, spent months sifting through the WPP archive. Her approach was not to create a “greatest hits” retrospective, but to identify recurring visual patterns — tropes that appear again and again, consciously or not, across 70 years of award-winning press photography.

‘For 70 years, World Press Photo has documented our visual history,’ de Middel says. ‘This exhibition is an invitation to rethink not just how our visual language has evolved but how we, as viewers and citizens, should be learning to read images with a sharper and more critical eye. If history repeats itself — and it does — then the way we narrate it has to evolve.’

De Middel and her team identified six recurring visual patterns that run like threads through the archive. Together, they offer a fascinating — and sometimes uncomfortable — map of photojournalism’s collective gaze.

Gendered roles in world crisis

Two patterns, Weeping Women and Men Rescuing and Being a Man and Being a Woman, reveal how press photography has often reinforced traditional gender roles. Women appear as mourners, caregivers or symbols of suffering. Men appear as rescuers, leaders, athletes — agents of change rather than subjects of it. Even in professional contexts, women’s images have often been framed with an emphasis on appearance over competence.

Conflict and its framing

The Emotional Soldiers and Debris category looks at how war is depicted — and who is granted humanity in its portrayal. White soldiers, often from Western forces, are shown in moments of vulnerability or contemplation. Soldiers with darker skin are more often depicted in active combat, reinforcing harmful stereotypes of aggression. At the same time, the destruction of war is sometimes rendered with a troubling aesthetic beauty — debris framed like art, the horror at a distance.

The colonial gaze

Perhaps the most pointed critique is in Black Skin and The Dark Continent, which highlights how Africa has often been framed through a Western lens — a continent of famine, war and suffering, stripped of nuance. Close-up studies of Black skin can carry echoes of colonial-era ethnography, reducing people to texture rather than personality

Beauty and spectacle

Finally, Silhouettes and Shadows — The ‘Wow’ Moment and Fire and Smoke examine how photographers seek visual drama. These techniques — the perfect silhouette, the billowing smoke cloud — can add power and urgency to an image, but also risk turning human tragedy into spectacle. As de Middel notes, the tools that make an image unforgettable can also distort its truth.

Why it matters now

For Joumana El Zein Khoury, WPP’s Executive Director, the exhibition is as much about the present as the past. ‘By examining recurring visual patterns, our aim is to create a space for collective reflection and open dialogue,’ she says. ‘In choosing to open up our archive in this manner, we also choose to be vulnerable. Acknowledging our past — its strengths and its flaws — is essential if we are to learn, evolve, and do better.’

In an age when misinformation spreads faster than ever, the ability to read images critically is no longer optional. The very ubiquity of photography — from breaking news to social media feeds — makes it easy to absorb visual narratives without questioning their framing. The WPP archive is a reminder that even the most celebrated, award-winning images are shaped by context, selection and presentation.

Looking forward

While What Have We Done? will physically be seen by visitors in Groningen and Johannesburg, its ideas are intended to travel further. WPP is exploring ways to bring the conversation online and into educational spaces, using the anniversary as a springboard for broader engagement about the ethics and evolution of photojournalism.

De Middel hopes the exhibition sparks more than nostalgia. ‘In seven decades, the three words that define this award — World, Press and Photo — don’t mean the same in 1955 as they do today,’ she says. ‘This exhibition acknowledges that shift while asking where we go from here.’

Perhaps that is WPP’s greatest strength at 70: not just in celebrating the images that have shaped our understanding of the world, but in questioning them — and inviting us to do the same.