From glass plates to flexible film, from simple snapshot to complicated professional cameras, from single lens reflexes (SLRs) to twin lens reflexes (TLRs), from analogue to digital cameras… AP’s 140 years have seen it all. Here are some of the landmarks encountered along the way.

The beginnings

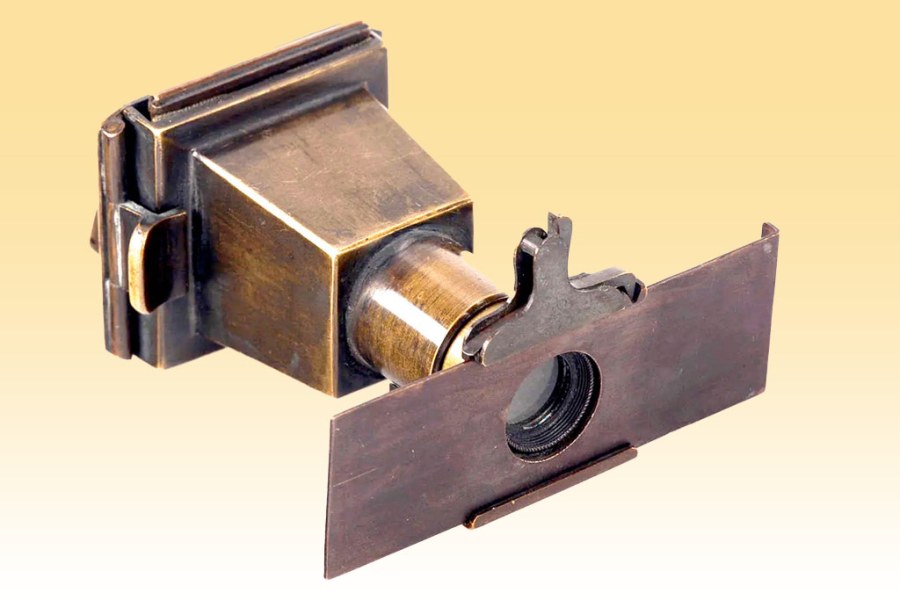

To kick off in 1884, what better than the only camera reviewed (and, in fact, the only illustration) in that first issue of AP? Marion’s Miniature Camera was an all-metal, nickel-plated brass design that shot 2x2in plates using a rapid rectilinear lens that focused on a ground-glass screen at the rear, with a fixed aperture and simple shutter. The Marion was quite a revolution for its time, but the major landmark came four years later when inventor and entrepreneur George Eastman aimed the first roll film camera at amateurs and called it The Kodak.

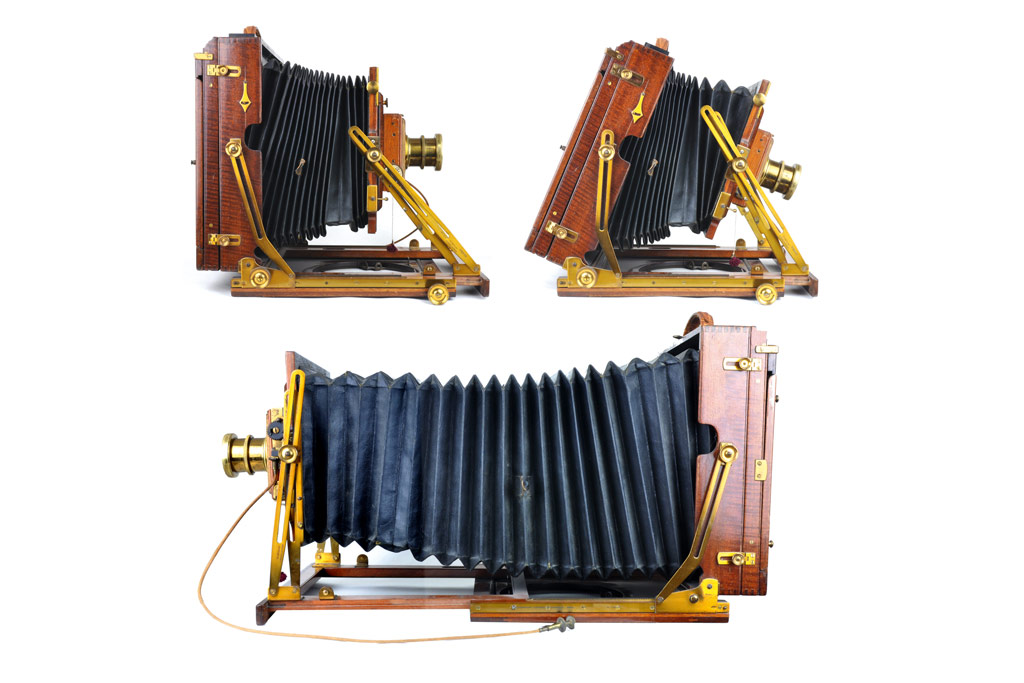

Professional photographers, meanwhile, clung onto their plate cameras and, in 1895, cabinet maker Frederick Sanderson produced a new kind of model to help with his interest in architectural photography. The Sanderson Universal Swing Front Camera used a lens panel supported in four slotted arms, two on each side and locked by small knurled nuts. Using these, the lens panel could be made to rise and fall like other cameras, but also to swing from side to side or tilt up and down. The versatility of movement gave a new degree of composition and perspective control.

The Kodak Brownie was born in 1900 and became one of the most iconic camera names of all time. In 1912 Kodak launched the Vest Pocket Kodak, the first camera to use 127 size film. The VPK, as it became known, was a folding design with the lens panel pulled out from the body on scissor-like struts. Early VPKs used a simple meniscus lens, soon replaced by a Kodak Anastigmat f/8. Varying apertures and shutter speeds, with exposure instructions printed minutely on a plate around the lens, made the camera more versatile for the serious amateur photographer.

Also in 1912, while 127 roll film was big news among amateurs, professional photographers were delighted to take delivery of the new Speed Graphic which, in many incarnations, remained popular as a press camera through to the 1950s. In other fields, the Hicro in 1915 simplified early colour photography by shooting three pictures on three plates through different coloured filters all with a single exposure. The Ensign Cupid in 1922 was the first camera to double the number of pictures taken on a single roll of film, an idea that took off in a big way with both 120 and 127 film cameras.

Big names hit the market

The 1920s also saw the arrival of the first Leica in 1925 and the original Rolleiflex in 1928. As the 1930s dawned the landmarks came thick and fast. In 1932 Zeiss Ikon produced the Contax I, the first 35mm camera to rival Leica, then went on to introduce the first series of Ikontas, marking the start of the company’s prestigious range of folding roll film cameras. Also in 1932 came the Mini-Fex, the first camera to use 16mm film, a new size destined, some mistakenly thought, to become more popular than 35mm.

In 1933 a Japanese company called Seiki Kogaku launched a 35mm camera inspired by the Leica II and called it the Kwanon. Before long the company changed the name of its cameras to Canon and the rest is history. The decade continued with more landmarks that included the 1935 Contaflex, 1936 Kine Exakta, 1937 Minox and the 1938 Super Kodak Six-20. Then, in 1939, World War II broke out and camera production stagnated until its end in 1945. In 1948 the Japanese Nippon Kogaku company looked at the Leica and Contax, then designed its own camera with features that owed something to both Zeiss and Leitz. So was born the first Nikon, a name that was shortly to be destined for worldwide fame.

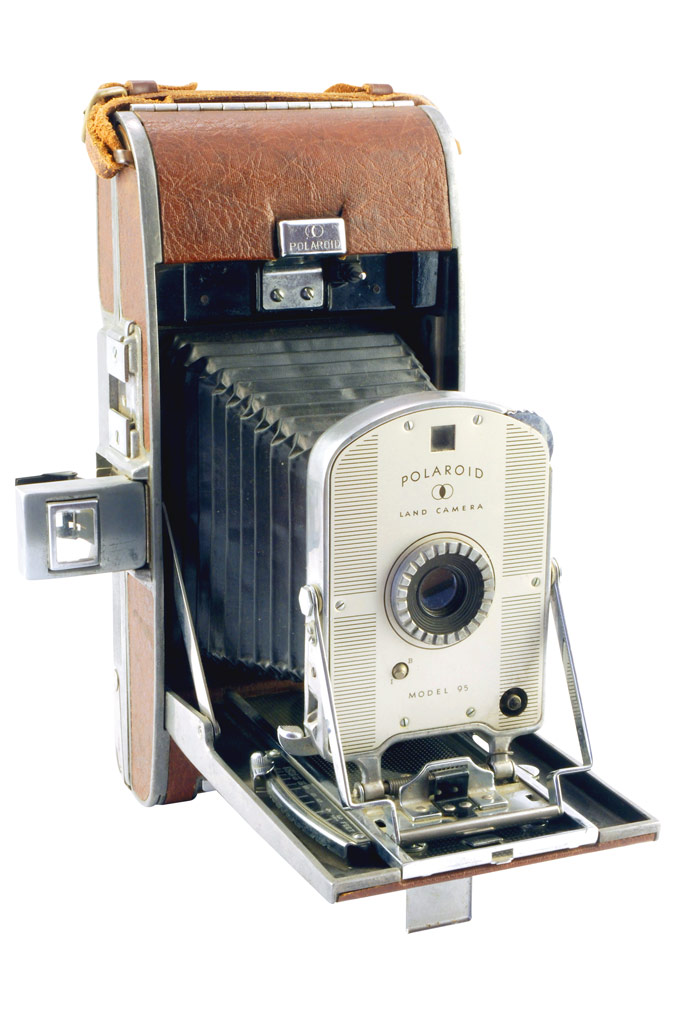

The year the Nikon I was launched also saw two more big hitters in the world of landmarks: the first Hasselblad followed by the first Polaroid instant picture camera. In 1954 Leica took the 35mm coupled rangefinder market by storm when it unveiled a totally new design in the shape of the Leica M3. Towards the end of the decade, Board of Trade restrictions – put in place after World War II to prevent certain luxury goods from being imported into the UK – were gradually lifted and so, in 1959, came the Nikon F. It kick-started a new wave of 35mm SLRs from Japan which effectively not only buried the 35mm rangefinder models that had dominated the market until then, but also beat the few German SLRs around at the time into the ground. The same year saw the introduction of the Olympus Pen, Japan’s first half-frame camera, leading in 1963 to the Pen F, the world’s first half-frame SLR.

Two important landmarks landed in 1963: the Topcon RE Super, the first SLR to use through-the-lens metering, and the first of Kodak’s Instamatic cameras. In 1972 Polaroid introduced its SX-70 system, the first instant picture camera to automatically eject a print immediately after exposure to self-develop in normal light, and the same year saw Olympus revolutionise the 35mm SLRs with the OM-1.

The first digital camera

In 1975 one of the most significant landmarks never seen in photographic history was revealed by Kodak behind closed doors, then put away in a cupboard and forgotten about. Big mistake. Built by scientist and electrical engineer Steven Sasson, this was the first digital camera. It used a CCD sensor, which in today’s jargon would be said to have a sensitivity of 0.01MP, needing 16 nickel cadmium batteries to run its functions. It also incorporated an analogue/digital converter salvaged from a digital voltmeter, the discarded lens from an old Super-8 movie camera and an adapted cassette tape recorder to save its images. Those who saw it likened its design to a toaster.

Fearing it might damage its film sales, not to mention its developing and printing business, Kodak took digital no further at that stage. It was Sony, in 1981, who produced the Mavica, a digital SLR with interchangeable lenses which might have been the first digital camera had it got any further than a prototype. Usable digital cameras took a step closer to reality in 1988 when Canon introduced the RC-250, known as the Xap Shot in America, Q Pic in Japan and the iON, in Europe.

Film fights on

Meanwhile, film camera manufacturers, not ready yet to acknowledge that digital was the way forward, continued to produce innovative cameras. Between 1983 and 1986 Canon produced its T-series, offering the sophistication of an SLR with a compact camera’s ease of use. The T-90 in this range was one of the last, and best, manual focus SLRs. Autofocus had begun in 1977 with a 35mm compact called the Konica C35AF, the world’s first autofocus camera. Polaroid followed the next year with the SX-70 Sonar Autofocus, which was the first SLR with an automatically focusing lens. The technology came to 35mm SLRs first via independent lenses with the autofocus mechanism built in, ready to be attached to manual focus SLRs. Early in the race in 1980 came the Rikenon 50mm f/2 AF in the common K-mount. The Canon 35-70mm f/4 AF soon followed for use with the company’s FD-mount bodies. Similar autofocus lens manufacturers included Chinon, Cosina and Vivitar.

In 1981 Pentax produced the ME F, the first SLR purpose-made for use with an autofocus lens, although the mechanism was still in the lens itself. Similar thinking was applied to the Canon T-80 and Olympus OM30 in 1983. And then, in 1985, the game changed forever with the introduction of the Minolta 7000, which transferred the autofocus mechanism to the camera body.

As the 1990s dawned it became clear that digital technology might soon foretell the death of film. Not that this dissuaded Kodak, Agfa, FujiFilm and Konica getting together to launch the Advanced Photo System (APS). With new types of camera, film and processing, it was reckoned that APS would change photography forever. It didn’t.

Digital wins the race

By now digital technology was emerging in a serious way, though held back by low sensor sensitivity and high prices. But, with a speed never before witnessed in camera development, sensitivity went up, prices came down and, almost without anyone noticing the sudden absence of film cameras, digital became the only game in town.

At first digital cameras were only available and affordable to most in the form of non-reflex compacts, of which there were many, including the 1995 Casio QV-10, the first with an LCD screen. Digital SLRs (DSLRs) began with companies coming together to put digital sensors on the back of adapted film cameras. Then the 1999 Nikon D1 became the first to be built from the ground up by a single manufacturer. In 2003 the Olympus E-1 introduced the Four Thirds system with the first lens mount designed specifically for digital photography. The Four Thirds system morphed into Micro Four Thirds in 2008. Also, in 2008 the Nikon D90 was the first DSLR to offer video recording, trumped the same year by the Canon EOS 5D Mark II with Full HD video shooting.

Previously, in 2000, the Sharp Electronics J-SH04 J-Phone was probably the first standalone phone camera, though it was available only in Japan. By 2011 the iPhone 4S with its f/2.4 lens and 8MP sensor was arguably the first phone to compete seriously with digital compact cameras.

Two years before, the mirrorless revolution had begun in 2008 with the Panasonic Lumix G1, the first interchangeable-lens camera to rely solely on electronic viewfinding. Three years later the not-so-successful Sony Cyber-shot RX1 was the first compact camera with a full-frame sensor, but it was another year before that sensor size found a home in the Sony Alpha A7 and A7R, the first full-frame mirrorless cameras. Then in 2017 the Sony Alpha 1 became the first mirrorless camera with a stacked-CMOS sensor. With this on board, when it came to autofocus shooting speeds, it could outperform any DSLR.

Since then there have perhaps been no really big innovations – unless you count the Pentax 17 launched earlier this year as a roll film camera that shoots half-frame images 72 to a roll of 36-exposure 35mm. What will they think of next?

The first snapshot cameras

In 1888 George Eastman’s Kodak represented not only the first use of this iconic name, but also the first camera to use roll film, introducing photography to a new generation who might never before have thought of owning a camera. It shot circular pictures 2½in diameter and came preloaded with enough film for 100 exposures. When the film was finished, the camera was returned to the Eastman works where it was unloaded, the film developed and printed and the camera reloaded with a new film.

In 1900 the Kodak Brownie, taking its name from elf-like characters created by Canadian author and illustrator Palmer Cox, was aimed primarily at children. The camera was a very simple box shape, its only controls being a shutter release and film wind knob. A separate viewfinder was available as an accessory and it shot six exposures 2¼in square on 117 size film. The No.2 Brownie, which followed in 1901, was the first camera to use 120 size roll film shooting eight exposures 2¼x3¼in. To the displeasure of Kodak, the term ‘Box Brownie’ went on to describe nearly every simple box-type camera, irrespective of its manufacturer.

Landmark 35mm cameras

The 1925 Leipzig Spring Fair saw the debut of the first Leica. Although there had been cameras that used 35mm film before, this was the first to make it truly viable for stills photography. The camera used a horizontally running cloth focal plane shutter. A 35mm cine frame measured 18x24mm, and the film ran vertically through the camera. The Leica ran the film horizontally, doubling up on one of its frame dimensions. So was born the 24x36mm negative size that became the standard for 35mm stills photography. In the years ahead a vast range of accessories and screw-fit lenses became available for many different incarnations of the camera.

Seven years after the first Leica, Zeiss Ikon introduced its rival, the Contax. The basic design was for a black, square-ended body, incorporating a vertically run, metal focal plane shutter with a film wind knob on the front of the body beside the lens.

A rangefinder was coupled to the lens, focused by a small wheel that protruded from the top plate. Ten interchangeable lenses were available, which were attached to the body by a bayonet mount.

In 1934 Kodak brought 35mm to the masses with the introduction of the Retina. At £10 10s (£10.50) it was less than half the price of a Leica or Contax. It was also smaller, lighter and folded into a pocketable package.

The 35mm spotlight returned to Leitz in 1954 with the introduction of a new model that replaced the screw-lens mount with a bayonet, lengthened the rangefinder base for more accurate focusing, made film loading easier, improved the viewfinder and wrapped it all up in a streamlined body. The camera was the Leica M3, which some claim was one of the most beautiful cameras ever made.

Birth of a legend

Although the basic concept of a TLR – the use of two lenses, a lower one to record the image, the one above to reflect its image to a viewfinder on the top of the body – goes back to the days of glass plate cameras, the Rolleiflex gains its landmark status for being the first compact, roll film model.

Its German makers, Franke & Heidecke, began by manufacturing stereo cameras that featured two lenses to take the twin pictures needed for stereo photography with a third lens between them for the viewfinder. At its heart, the Rolleiflex was a stereo camera turned on its side with one of the shooting lenses removed. The original Rolleiflex took six exposures 5.5x6cm on 117 size film, but some were converted to use 120 roll film. This first camera went on to inspire the design of all future Rolleiflex and Rolleicord cameras, as well as hundreds of other TLRs from makers around the world.

Metered automation

In 1935 Zeiss Ikon produced the Contaflex, a TLR that was the first camera with a built-in meter. The selenium cell, under a flap above the viewing lens, deflected a needle in a window beside the focusing hood, indicating shutter speeds and apertures which were then set manually. To provide a larger than 24x36mm viewing screen, the size of a standard 35mm image, the 5cm taking lens was matched with an 8cm viewing lens, allowing for a larger image, but cunningly linked to the taking lens so that focus remained in sync.

The Super Kodak Six-20 was the first automatic exposure camera. Light hitting a selenium cell across the top of the body produced an electrical current which moved a needle. First pressure on the shutter release locked the needle in a comb-like device, then a sensor connected to the aperture control adjusted the aperture until stopped by the locked needle. The camera shot eight pictures 6x9cm on 620 size roll film.

The first 35mm SLR

Although it was once thought that the Russian-made Sport was the first 35mm SLR, it’s pretty much accepted now that the accolade goes to the 1936 Kine Exakta. The camera featured a tapered body with a left-handed shutter release beside the lens, which was interchangeable via a bayonet mount. A range of standard, wide-angle and telephoto lenses was available, along with accessories that included extension tubes, bellows, microscope adapter and lens hoods. The reflex viewfinder was designed to be used at waist level. The shutter’s ‘B’ setting, used in conjunction with the delayed action knob, offered slow speeds down to a full 12 seconds.

A roll film reflex revolution

In 1940, during World War II, a German reconnaissance aircraft crashed in Sweden, and an aerial camera was recovered from the wreckage. It was taken to Swedish optical engineer and photographer Victor Hasselblad who was asked if he could manufacture an accurate copy of the camera. To which Hasselblad is reputed to have answered, ‘No, but I can build a better one.’

The result was a camera called the HK-7, which featured interchangeable lenses, shot 7x9cm negatives on 80mm wide perforated film and had a direct vision viewfinder mounted on top of the body. When the war ended in 1945, Hasselblad turned his attention to civilian cameras. The first model he produced was the 1600F, so named because of its high top shutter speed of 1/1,600sec. The camera comprised a body, to which could be attached an impressive range of interchangeable lenses, film backs and a variety of viewing systems, making it the first truly modular reflex camera to shoot 12 square pictures on 120 film.

The first instant picture camera

The Polaroid Model 95 introduced in 1948 was the first instant picture camera to deliver a finished picture to the photographer within a minute of exposure. It resembled a large version of folding cameras of the day, using a flap that dropped down from the body and a lens panel that slid along it on rails. Twin rolls of sensitised paper, connected by a paper leader, were dropped into opposite ends of the body with the paper leader threaded between two rollers and out of the camera. After exposure, as the leader was pulled, the exposed paper negative from one spool and the sensitised printing paper from the other came into contact, sandwiched between rollers. Pods of chemicals, consisting of a special developer and fixer in one solution and situated on the paper negative, burst under pressure, spreading the solution evenly between the two layers. The negative image developed first. Then the unused silver salts were converted to a soluble solution by the chemistry from the pods and diffused through to the print paper, thus producing a positive image. After 60 seconds a trapdoor was opened in the back of the camera and the finished print removed.

First TTL metering

The first camera with through-the-lens (TTL) metering was the 1960 Mec 16SB subminiature camera. But the first SLR with the feature and therefore the real landmark was the Topcon RE Super. It worked by use of a reflex mirror with a pattern of transparent lines etched into it, allowing some light to pass through the mirror to a CdS meter cell at the rear. From this, match-needle metering indicated correct exposure in the viewfinder and in a top plate window.

The start of the system SLR

From day one, in 1959, the Nikon F was designed to be the centre of a huge system comprising a wide range of lenses from 21mm to 1,000mm, the first electric motor drives, a choice of viewfinders and focusing screens, plus many other accessories. At a time when other SLR manufacturers were still using screw mounts for lenses, Nikon came up with its revolutionary bayonet mount which, in essence, is still retained today. In 1962 Nikon added the Photomic head, which replaced the standard eye-level pentaprism viewfinder, incorporated a CdS meter and linked to the shutter speed dial. A coupling on the front also conveyed the aperture setting to the meter. Before long, the Nikon F became the go-to 35mm camera for most professional photographers.

The Instamatic age

The barrier of film loading that dogged many snapshot photographers was lifted by Kodak in 1963 with the introduction of the first Instamatic cameras which housed the film in plastic Kodapak cartridges. The film was 35mm wide, wound with backing paper containing frame numbers to produce a 28x28mm image. The photographer had only to drop the cartridge into an Instamatic camera, snap the back shut and start shooting.

In 1972 the idea was revamped to make Pocket Instamatics. The 110 size film they took was 16mm wide, enclosed in a long, narrow cartridge and had a frame size of 13x17mm. Instamatics cameras from Kodak, and similar models from other manufacturers, ruled the world of snapshot photography until the introduction of Kodak Disc cameras in 1982. These never attained the same level of popularity.

The first compact SLRs

The 1970s was the decade when SLRs grew smaller. It began when Olympus introduced a camera called the M-1. Quickly realising that Leica had a camera with a very similar name, Olympus relaunched the camera in 1972 calling it the OM-1. Other than its compact dimensions, the OM-1 was a typical SLR of its time, with a 1–1/1,000sec focal plane shutter, a Zuiko 50mm f/1.8 interchangeable lens and match-needle TTL metering. Olympus followed with upgraded models while other manufacturers were fast to follow the compact design, most notably Pentax with the ME and ME Super.

Early digital

The Canon iON, among the first digital-type cameras to be commercially available, comprised a flat body with the 11mm f/2.8 lens at one end of the narrow side and a built-in flashgun at the other. It was actually a still video camera that incorporated an image sensor and processing hardware similar to those used in video cameras of the time. Single frames were extracted from the video signal and saved on a small magnetic rotating disc. To play back and view the image on a conventional television, the disc was rotated at the same rate and the appropriate frame read repeatedly.

First body-integral autofocus

In 1985 the Minolta 7000 took autofocus mechanisms out of the lens and placed them into the camera body. This reduced the lenses to about the same size as manual lenses in a camera body that was only marginally larger than its manual focus contemporaries. It was launched with 12 autofocus lenses from 24mm f/2.8 through to 300mm f/2.8. For use in low light, the camera utilised the near infrared AF-assist feature of the camera’s dedicated flashgun to provide instant focus readings. The 7000 also featured the world’s first automatic multi-program selection that involved taking data from the lenses and translating it into information that set the most appropriate exposure.

Professional DSLRs

Nikon entered the DSLR market by joining forces with Kodak, which stuck its own sensor on a Nikon F3 and later on an F-801S to produce huge, unwieldy cameras that cost around £20,000. Later, Nikon teamed up with Fujifilm to produce the strangely shaped Nikon E2 with a price drop to more like £16,000. But the Nikon D1 in 1999, the first DSLR to be built by a single manufacturer, cracked the £3,000 threshold, making DSLR photography practical for professional photographers.

Taking the shape of most film SLRs until then, the D1 had a top shutter speed of 1/16,000sec, five-segment matrix TTL metering, TTL phase detection autofocus and a shooting rate of 4.5 frames per second. The 23.7×15.6mm size sensor delivered a mere 2.7MP with images stored on CompactFlash cards. The D1 was followed by the D1X that offered a 5.3MP sensor and three frames per second continuous shooting, and the D1H that retained the 2.7MP sensor but upped its speed to five frames per second.

Full frame and mirrorless

The combination of a full-frame 24.3MP sensor with a mirrorless design and electronic viewfinder gave the Sony Alpha 7 its landmark status in 2013, leading very much to all the most popular high-end mirrorless models of today. A hybrid autofocus system with 25 contrast-detect and 117 phase-detect points combined with on-chip phase detection allowed five frames per second shooting with continuous autofocus. The camera was also considerably smaller than its peers. Although capable of accepting the existing E-mount and, with a suitable adapter, A-mount lenses, the Alpha 7 was launched with five lenses in the new FE series. Within two years, ten more lenses had been introduced. The viewfinder could be switched between full-frame and APS-C modes depending on which lenses were attached. The Alpha 7’s companion camera, the Alpha 7R, upped the sensor resolution to 36MP but only used the slower contrast-detection method for autofocus.

Related reading:

- 140 years of Amateur Photographer

- 140 years – a lifetime of landmark cameras

- 140 years – What AP means to me

- Life in the past lane – Photography in 1884