It was an unusually warm, early June Friday afternoon as Sean and I plopped down into striped deck chairs in London’s Regent’s Park. I first met Sean in 2002 when we were paired together on assignment for Men’s Health magazine to produce a report on male longevity in Martinique and Belarus. He wrote the words, I took the photographs.

Twenty-one years later, together we’ve covered stories across India, Egypt, Germany, Israel and many places in between. He’s a trusted friend and I trust his choice in wine. We sipped back a Pouilly-Fumé and chatted about our daughters, current affairs and story ideas.

A ragged Ukranian flag flies over the Black Sea. Photo: Peter Dench

‘My mate Ben, ex-SAS, says you can fly direct from London to Chisinau, the capital of Moldova, then drive three hours to the war in Odessa, Ukraine,’ said Sean. ‘That’s interesting, we should go,’ I said.

A quick Google confirmed the idea and even better, that you could take the bus. As the French white turned into a Greek Chardonnay, we discussed details, compared diaries and scheduled departure for early July. Over the following weeks I chatted with my editor at Getty Images and consulted colleagues who’d covered the conflict in Ukraine.

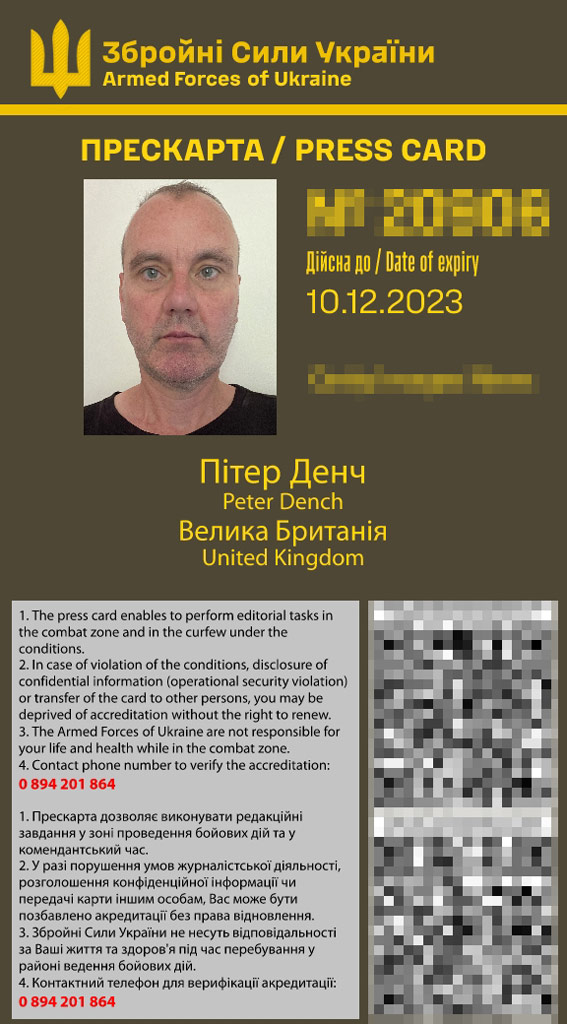

The advice was unanimous – get Ukrainian military-approved press accreditation. After a bit of form filling, eight days after emailing the application, it arrived:

- The press card enables the user to perform editorial tasks in the combat zone and in the curfew under the conditions.

- In case of violation of the conditions, disclosure of confidential information (operational security violation) or transfer of the card to other persons, you may be deprived of accreditation without the right to renew.

- The Armed Forces of Ukraine are not responsible for your life and health while in the combat zone.

5.5KM from the beach, a Fozzy Group hypermarket was destroyed in a missile attack which led to a fire burning everything. Photo: Peter Dench

On 12 July 2023, Sean and I sat in departures at Luton. The horror of negotiating Luton Airport was good preparation for war. We were keen to leave. The flight was scheduled to depart at 21:30. Waiting around had been hard. I’d repeatedly thought myself into a dark place. Why was I going? What did I hope to achieve? Could I afford it? Am I over- or under-prepared? What’s wrong with being a house husband and present father? Maybe it was to impress my own father? Was I going as a journalist or voyeur? Am I just fed up with members at my tennis club banging on about trips to Tuscany and the Maldives? With my daughter about to leave home for university and wife about to turn 50, was this my Maserati mid-life crisis?

Honor Guard of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (Transnistria) perform on Republic Day in the capital Tiraspol. Photo: Peter Dench

Our flight was delayed by two hours. Then cancelled and rescheduled for 14 July. That flight was cancelled and not rescheduled. FlyOne, the privately owned, low-cost airline headquartered in Chisinau, refused to refund the €526. My travel window had closed. Sean, unable to face unpacking, decided to make his way to Lviv, Ukraine, via Poland. Our diaries had diversified. The next opportunity I had to travel would be alone.

Planning for war isn’t easy. In between family holidays and work commitments I managed to negotiate 11 days. Leave on 23 August and arrive in Odessa in time for Ukrainian Independence Day on the 24th. Then head to the Russian-backed Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (Transnistria) for their 2 September Republic Day celebrations. Effectively I would be visiting two opposing ideologies across two weekends.

A statue of Lenin outside the monumental palace of the Supreme Council (Parliament) and the Government of Pridnestrovie located near the central square, in the historical center of Tiraspol. Photo: Peter Dench

Internationally, PMR is recognised as part of Moldova but has been independent since 1992, after a short but bloody civil war. Around 1,500 Russian troops are stationed there and act as peacekeepers. The northern village of Cobasna hosts what is widely believed to be Eastern Europe’s largest ammunition depot. The capital, Tiraspol, is a 110km march from Odessa.

It would be a story of sun, sea and sandbags, contrasting the destruction of Odessa with families on the beach and fortifications within the city. Highlighting the fragility of its position in the region but also shining a light on humanity’s lust to survive in the most challenging of circumstances. It would be my visual contribution to this complex and unfolding chapter of history.

I limited who I told I was going to Ukraine. Partly because I wasn’t 100% sure I’d get there, mainly because the advice, while well intended, was unhelpful. Like revealing you’ve got cancer, people feel compelled to comment and assume the worst. One friend regurgitated his experience of nearly being kidnapped in Beirut. Another advised that Russian infiltrators were informing on journalist’s hotels and guiding in missile attacks.

Most just said ‘be safe’ or ‘don’t die.’

After a last-minute assignment for The Sunday Times reporting on the heatwave in Alicante, a day later than I’d hoped, on Ukrainian Independence Day and avoiding FlyOne, I finally boarded a Wizz Air flight to Iasi, Romania.

Ticket to war

Having stayed overnight, in the morning I took a four-hour bus ride to Chisinau. Less than a minute after crossing into Moldova, I witnessed three horses and carts and a goat on a lead. Every road junction had an effigy of Jesus and we immediately got stuck behind a tractor. People fed stray dogs. The driver matched the deterioration of the roads by overtaking one-handed. A man threw stones at a chicken. Vodafone informed me I was in a Zone D worldwide destination. It felt like it.

The Republican Cadet Corps of PMR during Republic Day celebrations in the capital Tiraspol. Photo: Peter Dench

At Chisinau I upgraded to a bigger bus. A €20 one-way ticket to war and began deleting sensitive social media posts and suspending online content. In 2018 I’d spent three weeks in Russia reporting on the World Cup and travelling the Trans-Siberian railway. I’d photographed Russian soldiers in transit and been photographed wearing a Putin T-shirt. It seemed ironic at the time and times had drastically changed.

A woman poses with a firearm on a visit to Tiraspol for Republic Day celebrations. Photo: Peter Dench

Relentless

The bus had more of an atmosphere of travelling to a water park than a city on the receiving end of repeated Russian attacks. On 11 July, Russia launched an overnight drone strike on Kyiv and Odesa. Ukrainian authorities reported no casualties and that 26 out of 28 drones launched were shot down. On 18 and 19 July, Odessa port was relentlessly attacked after Russia pulled out of the grain deal. On 23 July a Russian missile attack on Odessa killed one, injured 20 and severely damaged an Orthodox cathedral in the city centre, 750m from the hotel I’d booked to stay in. As I recalled these events, children on the bus played on tablets or laid on mother’s lap. Entering Ukraine, a rainbow arced the bus, I was literally somewhere over it, where armed soldiers peered from pillboxes.

Transfiguration Cathedral damaged by a Russian missile strike on Odessa. Photo: Peter Dench

‘Dear Peter, Thank you for choosing Alexandrovskiy Hotel! We will be glad to welcome you and help to feel our hospitality. We kindly offer you to use our additional services during your stay: transfer and taxi; bike rental; massage.’ Checking in, I was pleased to see another service; bomb shelter. Within two hours of arriving in Odessa, the evening was ruptured by air raid sirens. I didn’t know what to do or where to move. Odessa was the left, right, back and front line. An air raid siren is like air turbulence, it’s uncomfortable, you’re not sure how long it will last and it’s unlikely you’ll die. I did what most of the locals were doing, carried on as usual and popped into a bar that served wine by the 100g (I’m used to dealing in kilos).

Dench on duty in Ukraine with his OM System OM-5

Anti-tank obstacles

In Odessa, everything was normal until it wasn’t. A woman sunbathed in a bikini as military personnel paddled in the Black Sea. Children dive-bombed metres from anti-mine nets. Commuters negotiated ‘hedgehog’ anti-tank obstacles. Adverts for fashion brands shared billboards with patriotic messages. Teenagers played volleyball in the shadow of a bombed-out building. Dog walkers rested on benches beside painfully young military cadets, necks bruised from a lover’s bite.

A paddle in the Black Sea for two wearing Ukrainian military fatigues. Photo: Peter Dench

I fluctuated from being hyper-happy to paralysingly paranoid. The war raged in my head. Munching sea bass in the sea view terrace I mistook an incoming drone for a dirt spot on the window. On the way to my hotel, I admitted to my taxi driver I was British press then convinced myself he was one of those missile-guiding Russian informers.

A woman passes ‘hedgehog’ anti-tank obstacles on the perimeter of Savytskyi Park near the railway station and District Court. Photo: Peter Dench

After five days in Odessa I left for the Kremlin-backed PMR. The paranoia didn’t abate, it escalated. The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office advised against all travel (same though for Ukraine). As the PMR doesn’t officially exist and is outside the control of the Moldovan authorities, consular support is very limited. Western press weren’t encouraged.

The opening of the beaches has been a welcome respite from the tensions of war. The fight for normality by residents and visitors in the city described as the pearl of the Black Sea relentless. Photo: Peter Dench

In a recent Times report, Sergey Lavrov, Putin’s foreign minister, had described Moldova as the next Ukraine. In February, Moldova’s president Sandu said they had thwarted a coup that would have involved Kremlin agents seizing government buildings and taking hostages. I was going to PMR as a tourist. I shredded my Ukrainian military press pass and supporting documents. The Ukrainian stamps in my passport were a sore thumb. At the bus depot I had one last squidge of paranoia and hid my memory cards used in Ukraine in the lining of my luggage.

Ukrainian military cadets relax in a park during a break from training at the academy in Odessa. Photo: Peter Dench

At the border checkpoint for PMR I disembarked the bus and took my place in the queue. I was prepared to be asked how many days I was staying and where. I wasn’t prepared when asked: ‘Do you have a camera or just a phone?’ On my shoulder was a Domke bag with over 12kg of kit. ‘I have a camera,’ I replied, terrified of being searched. ‘Is it a professional camera?’ they asked. An interesting question. Is a professional camera any camera in the hands of a professional? Is it a professional camera when a picture taken on it is sold? It wasn’t the time for debate.

‘It’s not a professional camera,’ I lied. ‘Show it to me,’ they said. I pulled out my OM System OM-5 with a 12-45mm lens. They showed it to a colleague and handed it back along with my migration card.

A woman poses for photographs with soldiers on Republisc Day in Tiraspol by a T-34 tank monument to the warriors who died liberating the city of Tiraspol in 1944 during the Great Patriotic War. Photo: Peter Dench

Hammer and sickle

The OM-5 may have not looked professional to PMR border guards but it more than did the job and helped me feel inconspicuous. I photographed the red, white and blue Russian flags flying alongside the red and green of PMR, the only state in the world that uses the hammer and sickle on its flag.

I snapped comfortably on the streets named after Russian poets, writers and significant dates; 25 October Street, 1 May Street with busts of Lenin and Soviet symbols outside administrative buildings. On Republic Day I wielded the OM-5 unchallenged during the military- style celebrations amongst mean-looking men wearing earpieces.

PMR Honour Guard march through Tiraspol on Republic Day. Photo: Peter Dench

A woman startled me. ‘Are you a tourist?’ ‘Yes,’ I said, raising my camera. ‘Are you taking photographs?’ she continued. ‘A few, mainly monuments,’ I replied. ‘Are you on Instagram?’ she asked. ‘No I’m not,’ I said. ‘I’d like to practise my English, what hotel are you staying at, perhaps we could meet later?’ I wasn’t going to be caught out by KGBridgette! Remembering my Ukrainian taxi faux-pax I calmly replied, ‘No thank you,’ and moved on to photograph children wrestling, boxing and weightlifting in the park.

A simple idea in a Regent’s Park deck chair proved anything but. A direct flight and bus turned into an indirect flight, four countries, five hotels, 24 hours on six buses, missed buses, cancelled tickets, six border crossings and several unspoken languages. My original budget of around £1,500, obliterated.

For someone who considers getting out of the shower without using a hand rail a risk, a war excursion was a bold decision. I’ve no regrets and learned a lot. I was more likely to die from sunstroke, alcohol poisoning, poorly maintained vehicles or mosquito bites than a missile attack. Would I have liked to have experienced one? Most of me was jubilant I hadn’t. Maybe when I’m 71 I’ll be ready for the front line.

Dench’s kit bag: OM System OM-5, 12-45mm F4.0 Pro lens, 12-100mm F4.0 Pro lens, FL-600R Flash.

Related reading:

- Photo companies respond to Ukraine conflict

- Ukraine: an interview with Skylum CEO Ivan Kutanin

- Powerful WPP 2023 Photo of the Year shows devastation in Ukraine

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.