Eminent American inventor Thomas Edison said it best: ‘To invent, you need a good imagination and a pile of junk.’ Edison died in 1931 and the first digital camera didn’t appear for another 44 years. But his words might have resonated with electrical engineer Steven Sasson, the man credited with inventing that first digital camera, cobbled together from a miscellany of seemingly disassociated parts.

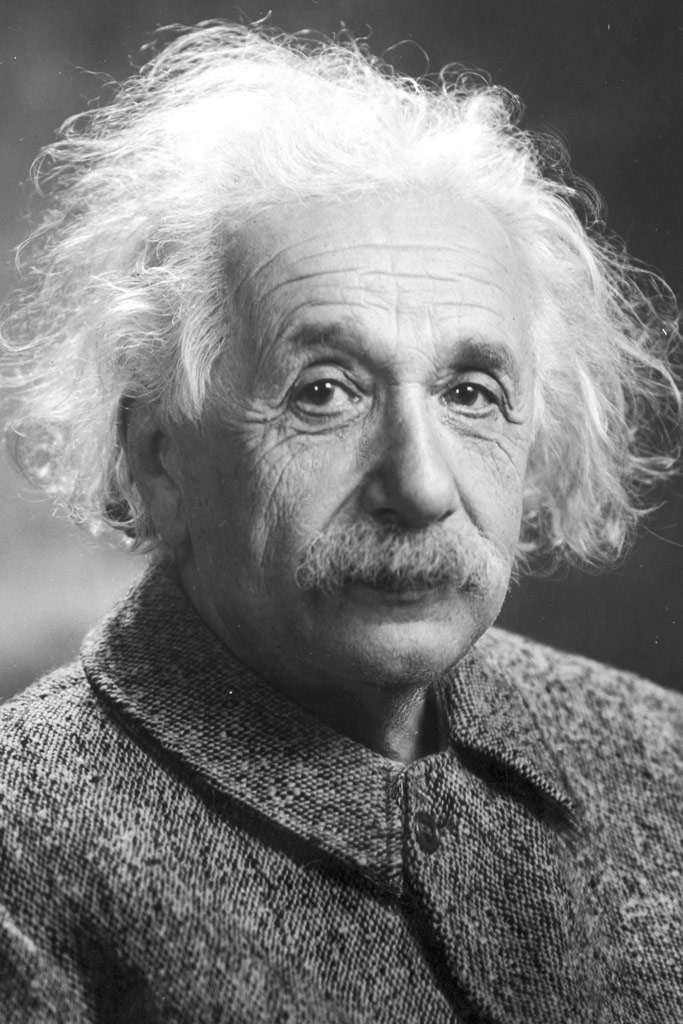

But to begin at the beginning, let’s talk about Albert Einstein. During the early years of the 20th century, scientists had already discovered that when certain metals such as selenium are exposed to light, an electrical current is generated. The problem was, they didn’t know why. Light, they reasoned, was in the form of waves and surely lacked enough power to energise electrons in the way needed to produce a current. Einstein thought differently. Suppose light didn’t come in waves, but instead behaved like particles that contained their own energy? If the frequency of these light particles was high enough, they could transfer their energy to electrons in the atoms of some metals, causing them to be ejected. Thus, when light hit the right metal, it would result in the generation of a weak electric current.

Fast forward now to 1969 where we meet physicists William Boyle and George E Smith at Bell Labs in America. They conceived what they termed a Charge Bubble Device. Leapfrogging the need to comprehend too much about semiconductor development, it is sufficient to understand that their discovery was a device that could be injected with electronic data.

And here’s the relevant bit: that electronic data could be derived from the electric current generated when light hit certain metals. This meant a method had been discovered of capturing a two-dimensional pattern of light and transferring it into an electronic signal. They had, in fact, created an early form of the charge coupled device (CCD) that would later lie at the heart of most digital cameras. Go back to photography’s early days and it would have been like inventing film before having a camera to put it in.

Enter Steven Sasson. As a child, growing up in America, he had been fascinated by electronics. At the age of 13, he had been in trouble with the Federal Communications Committee when an amateur radio apparatus he built accidentally sent out a signal on a banned frequency. After attending Brooklyn Technical High School, he went on to graduate with a bachelor’s and master’s degree in electrical engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. In 1973, aged 23, he took a job at Eastman Kodak in the apparatus division of the company’s Applied Research Department.

Sasson’s place in digital history began inauspiciously when his supervisor suggested that, as a broad assignment with no particular urgency, he might try to produce an electronic camera that used a CCD to capture its image. It was known by now that a CCD could capture data, but couldn’t retain it.

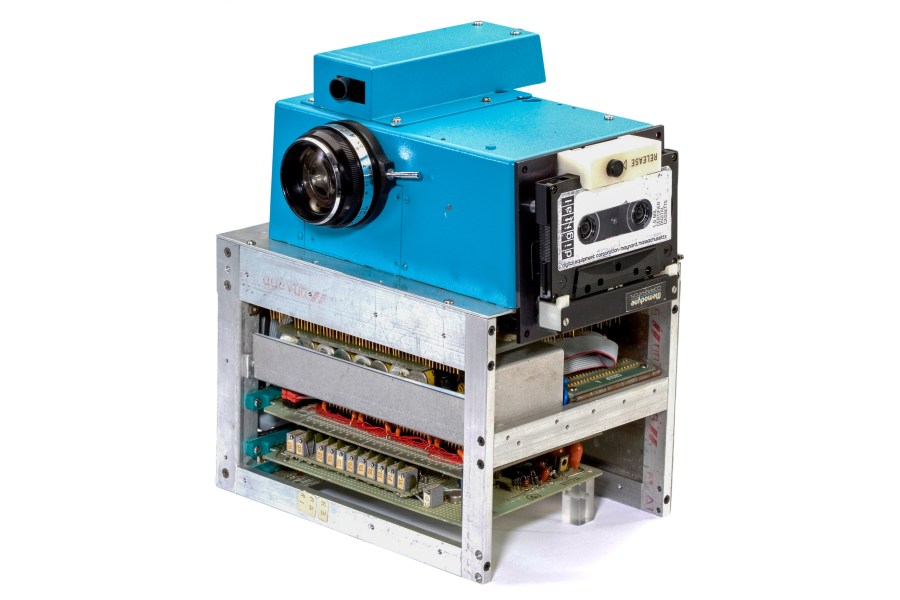

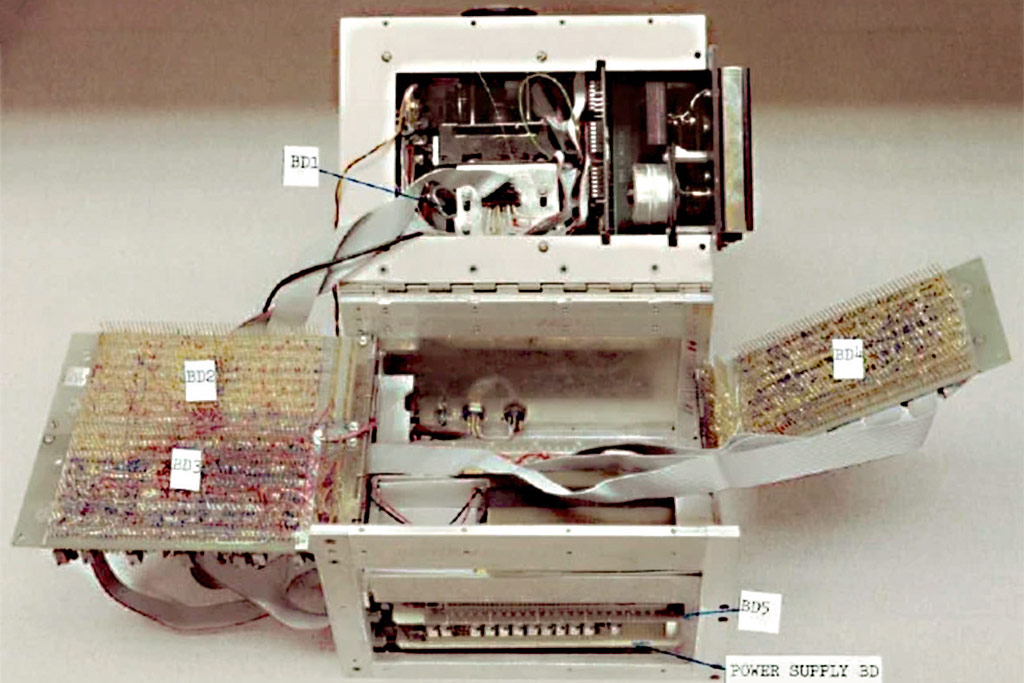

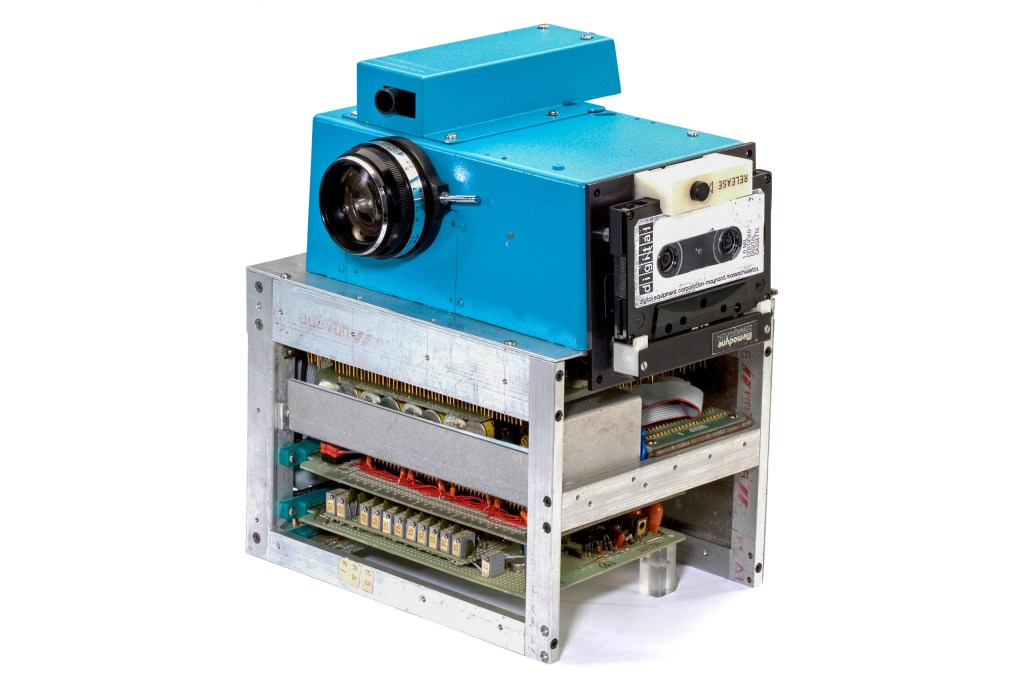

Computers were by no means commonplace in the work environment back then, but the theory of how analogue could be converted to digital information was known. So an analogue/digital converter from a digital voltmeter was used to digitise analogue data from the CCD which could then be stored on magnetic tape in a cassette recorder of the type then taking over from vinyl records for playing music.

Six circuit boards, 16 nickel-cadmium batteries and the lens from an old Super-8 movie camera were added to the mix, together with the invention of a device to play back the camera’s images on a normal television.

After two years of development, Sasson completed a working camera in 1975.

The first-ever digital picture was taken in December that year. The subject was a portrait of a fellow technician named Joy Marshall as she worked at a teletype machine. The picture wasn’t saved and no longer exists.

The camera weighed 3.6 kilograms and used a single-speed electronic shutter of 1/20sec with an infrared blocking filter. It took only 50 milliseconds to capture the image, but 23 seconds for it to be recorded and stored on magnetic tape. Each tape could store up to 30 images. When the tape was removed from the camera and placed in the playback device connected to a television, it took another 30 seconds for it to appear on the screen. The image was black & white and measured 100×100 pixels. In today’s jargon we would call that a 0.01MP camera.

Picture the next scene. A group of Kodak executives, not knowing quite what to expect, are confronted by Sasson, carrying a device that looks a little like a toaster. Before saying anything he points the device at his audience and takes pictures of them. Then he removes a tape cassette from his machine, places this in his playback device connected to a television and in less than a minute pictures appear on the screen. The demonstration was greeted with confusion, curiosity and scepticism. The reasons for the lack of an exultant reaction were basically threefold:-

- The image quality was poor and no threat to the kind of pictures being produced by 35mm film, or even the images from 110 snapshot cameras of the time.

- In a world where colour prints were universal, they saw no way that people would want to crowd around a television to look at black & white pictures.

- And maybe this was the most significant reason for any lack of enthusiasm. Assuming advances in technology would eventually improve the image quality, and speculating that those images might soon be in colour, what they were looking at was something that threatened to replace film and processing. And from what did Kodak make the lion’s share of its profits? Answer: film and processing.

Nevertheless, Kodak patented Sasson’s camera and he was allowed to continue his research. He ascertained that, if he was to produce a digital picture in colour whose quality at the very least matched that of a print from a 110 film negative, he would need 2 million pixels. He clearly had a long way to go.

Asked by Kodak bosses how long it would take to produce a consumer camera he had no quick answer. But resorting to his own interpretation of Moore’s Law – a principle that states that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit doubles every two years – he suggested it might take 20 years.

In 1995 Kodak introduced the DC40, the company’s first consumer digital camera, by which time the digital pioneers had been eclipsed by the likes of Sony, Apple and Canon, to name but three. And so Kodak became an also-ran in a race that it had so spectacularly started but which it was destined never to win.

Sasson’s digital camera patent expired in 2007. In 2009, he was awarded the American National Medal of Technology and Development. He received the British Royal Photographic Society’s Progress Medal in 2012. It was the same year that Eastman Kodak filed for bankruptcy.

The other first

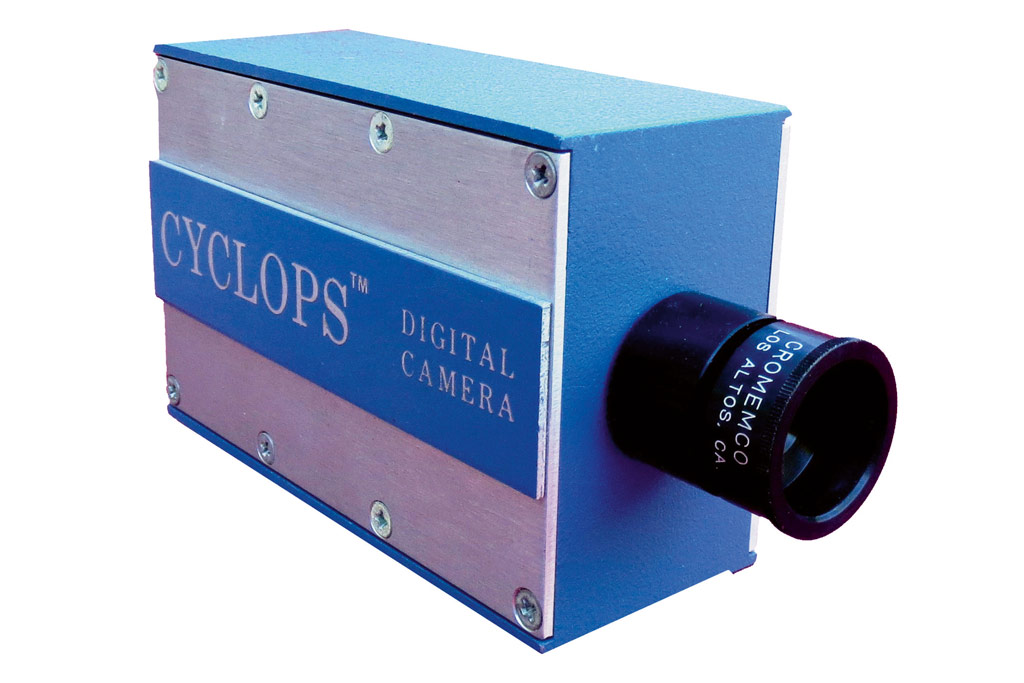

Although Sasson’s camera is universally recognised as the first digital model, there are stories about another that might have just preceded it. An article in the February 1975 issue of the American magazine Popular Electronics described a do-it-yourself project for readers to build their own solid state TV camera. A company called Cromemco took this up, built the device on a commercial basis and announced it as a digital camera designed to interface with an Altair 8800 computer. They called it the Cyclops, and it produced an image of 32×32 pixels. But unlike Sasson’s camera, which was the first to combine capture, analogue-to-digital conversion and file storage in one device, Cyclops had no built-in storage device.

Related reading:

- Vintage digital cameras you should actually buy

- The best cameras for photography

- What are the best second hand cameras?