Wildlife photography is not just about telephoto lenses and travelling. It’s a speciality that requires patience, skill and respect for the animals and the environment. Being a responsible and ethical wildlife photographer can be a minefield. Peter Dench sources some essential guidelines from ethical experts working in the field.

There are few better pursuits in life than grabbing your camera and striding into the great outdoors to immerse and engage in the natural world. The drive to get the shot can become maddening, and obsessive.

With no centralised industry resource on what is and isn’t acceptable, moral boundaries can blur to the point of illegality. Opinions on how to behave as a wildlife photographer, wildly differ. Lines are drawn, and choices are made.

Photographers can’t all be expected to be experts in animal behaviour but do have a duty of care. A deep love of nature is paramount, and every life form is treated with equal importance: invertebrate, amphibian, reptile, bird or mammal.

Nature stories need to be told and great photographs can still be achieved within ethical confines. If you’re asking yourself uncomfortable questions about whether your approach to photographing a subject is ethical, then it most likely isn’t. You have to learn to tread carefully.

Guidance for being an ethical wildlife photographer

Is live baiting allowed in wildlife photography?

Should live bait be used for the purposes of photography; are you even a wildlife photographer if you do? The industry swell is to reject live baiting – photography shouldn’t mean the death of an animal.

The Wildlife Photographer of the Year (WPY) rules state: Live baiting is not permitted, and neither is any means of baiting that may put an animal in danger or adversely affect its behaviour, either directly or through irresponsible habituation. Any other means of attraction, including birdseed or scent, must be declared in the caption for the Jury and us to review.

Neil Aldridge is open about his approach. ‘I do not live bait my subjects. If I aim to attract an animal for photographic purposes, I use scent baiting which involves the careful placement of a strong-smelling naturally occurring food derivative, such as honey or oils (depending on the subject).

This practice limits the impact on my subject’s actions, expectations and, importantly, relationships with people other than myself. There are species that will only hunt live prey like kingfishers; you either do it by live baiting or you do it by spending a long time waiting and perfecting your craft. It is possible.’

Can wildlife photographers use tape lures and traps?

Recorded bird songs played to attract birds may seem ethical but can adversely disrupt natural behaviour. Will Nicholls has reservations: ‘You should never use tape lures during breeding seasons as this can disrupt a bird’s normal patterns of behaviour. For example, when a male should be defending its territory from real intruders, it may instead spend its time trying to fend off the non-existent bird you are imitating.’

A non-intrusive way to capture wildlife is to use a camera that fires automatically when an animal is detected. To turn your DSLR into a trail or camera trap, all you need is a sensor that can detect animals which then triggers your camera.

It can then be left for days or weeks at a time once set up. It may not be photography at its purest but the longer you leave it, the greater your chances of capturing an ethical frame of an elusive animal.

Will Nicholls is an advocate: ‘Camera traps are becoming incredibly fashionable and it opens up a whole new unseen world to wildlife photographers. In fact, I’d go as far as to say that camera trapping is extremely addictive. The entire process, from setting up your DSLR camera trap to checking it weeks later for the results, has a real thrill about it.’

They can have setbacks, as Neil Aldridge explains: ‘When you use camera traps you can make mistakes like putting the camera on motor-drive. If you take two or more pictures, the first picture you get a natural-looking picture – the animal’s not aware of the camera when the flash and shutter go off. The next picture is the surprise at what’s happened and the third picture is it running away.’

How wildlife photographers should handle subjects

Nicky Bay shares his point of view on the temptation to handle or immobilise animals for better photographs: ‘It requires many years of training to be able to exert the precise force in handling any tiny subject without causing any injury or death.

Attempting to handle them directly is strongly discouraged. It is natural for subjects to run about. Forcefully holding a subject’s leg to prevent it from moving can lead to permanent injuries to the subject.

In the wild, many living things only eat once in many days. Some spiders have to use up a lot of silk just to get one prey. Be mindful that touching these subjects or stressing them may lead them to drop their precious prey and essential food for the week.’

Instead of trickery learn how to take better wildlife photos by studying animal behaviour.

Avoid distress in wildlife photography

Understanding and empathy for subjects are important to Gil Wizen: ‘Photographs of small animals can be a great tool for communication and education by revealing the hidden beauty of overlooked creatures.

However, we tend to forget how things are from their perspective. They do not like to be cornered or pushed around. The last thing they expect is a giant being trying to manipulate them to pose in a certain way.’

Putting your mirrorless camera on silent mode or using a telephoto lens with close focus can maintain enough distance to allow your subject to behave naturally. For macro shots, use longer focal length macro lenses. Portable hides and camouflage allow the documenting of wildlife without disturbing them.

Don’t deliberately draw attention, as Will Nicholls explains: ‘Intentionally spooking an animal by shouting or throwing objects towards it can be more problematic than you might think. Not only is there an unnecessary energy expense in an animal’s flight response, but you could be scaring a parent bird away from a nesting site.’

Drones have huge potential for ethical research but should be used with caution. A 2015 study documented the effect of drones on the heart rates of black bears in Minnesota and found that though there were no outward signs of stress, bears’ heart rates rose by as much as 123 beats per minute above the pre-flight baseline when a drone was present.

How to respect wildlife habitat as a photographer

Entering an animal’s habitat inevitably has an impact. Keep noise to a minimum, apply discretion and don’t move or destroy vegetation for a clearer view, let nature envelop you as a photographer: ‘Serendipity being what it is, other things happen if you are open and aware. If you have a love and awareness of nature you begin to see things.

After you’ve been a certain length of time by any bit of water or whatever, nature just accepts you; you’re there and it ignores you. You’ve got dragonflies and mayflies around you, you’ve got a hundred opportunities,’ advises Paul Harcourt Davies.

Artificial scenes

‘A nature photographer documents nature, so staging artificial scenes may present a false representation of nature. If it has to be done for art, it should be clarified that the subjects were artificially coerced into certain behaviour, positions or habitats.

Some scenarios are biologically impossible so fake captions and descriptions tend to fall through. Photos of artificially transported subjects may also provide false information to researchers on its natural habitat,’ suggests Nicky Bay.

Paul Harcourt Davies prefers to construct his images in situ: ‘I’m not an artistic photographer. I find it slightly arrogant that some people look upon nature as their canvas and they interpret nature in some ways. I have an innate love of nature and my rule is to try and reveal often things that are hidden using whatever ability I can summon technically but also with arranging elements in a picture that makes something attractive.

Usually, I look for design in pictures and shapes and interaction and so on. It’s a communication thing; fundamentally I’m out to try to make people aware of what’s out there and is worth protecting and saving. If people use their photography as a basis for finding out facts about plants and animals it engenders a greater love and appreciation of the subject – people become a lot more conscious of wanting to protect and to preserve.’

Game farms and photo tours

Captive animals offer a convenient way for photographers to practise technical skills and add species to their portfolio and stock photography that they may not have the chance to photograph in the wild: snow leopard, lion, bear, wolf.

Arguments for the benefits of game farms are that you don’t travel to remote locations to spend days or weeks staking out an animal in the wild, which reduces pressure and intrusion on fragile habitats. At the more distressing end of the spectrum, many farms have a less than exemplary record for animal security and welfare.

Reports suggest tigers being illegally de-clawed and the use of a cattle rod on a bear make it growl for the camera. When the animals are of no use for pictures they’re potentially sold off so people can shoot them. In 2012, an animal trainer employed by Animals of Montana game farm was mauled and killed by a bear.

Live or maimed mammals have been used to lure animals in front of the lens of paying customers. Neil Aldridge organises tuition and tours from the Cairngorms to Botswana, and has his approach: ’The industry has become high yield where everyone wants things quicker.

If you pay the money you want the shot. You’re not only paying for the equipment but you’ve only got seven days of holiday a year and you want to go to the Arctic and come away with the photo of the snowy owl.

That expectation has developed because of the success of photo tours. If people do choose to travel with me they do so on the understanding where I’m coming from. I never put anything into an itinerary saying we’re going to set this up. We will visit photography hides but there’s water there and the animals are free to come and go as they want – we’re not going to bait or live bait.’

Using external lights for wildlife photography

Most nocturnal animals are extremely sensitive to light. The National Audubon Society, an American non-profit organisation dedicated to the conservation of birds and their habitats, states in its guide to ethical wildlife photography: ‘Photographing animals at night, the practical approach is to use flash. Use flash sparingly (if at all), as a supplement to natural light.’

To capture his photographs of the grey long-eared bat, Neil Aldridge photographed with red light filters over nine flashes. ‘Our current research shows they aren’t impacted by red light. I use flash sensitively and only when necessary.

Wherever possible, I use off-camera flashes placed widely so as not to trigger directly into the eyes of my subject and at greatly reduced power output. I do believe that flash use has its place in photography. But only when used considerately and with knowledge of the specific subject in mind. I also remain open to learning from scientific findings around the impact of flash use in photography, both underwater and terrestrial.’

As a stress-free option for the animals read about capturing nocturnal animals in low light and our low light wildlife photography tips.

Fakery and manipulation

Be wary of viral photographs on social media – a frog riding a beetle, a snail riding a frog riding a turtle or five frogs riding a crocodile are likely to be fake. Cute or funny could mean cruel or deadly with subjects being glued, clamped, taped, wired, refrigerated, shaken or killed before being positioned for a photo.

A public community Facebook page by concerned nature enthusiasts, Truths Behind Fake Nature Photography, is trying to educate by highlighting fakes when they spot them. One of the most notorioius examples is José Luis Rodriguez’s shot of an Iberian wolf jumping over a fence (below).

After the Wildlife Photographer of the Year judges found he was likely to have hired a tame wolf (!) he was stripped of the overall winner prize in 2010.

After the shoot

Think before you publish your photographs and be accurate but sensitive in the caption. Sharing an image could alert poachers to a rare breed, nest or plant. Check carefully that you have labelled a species correctly, too.

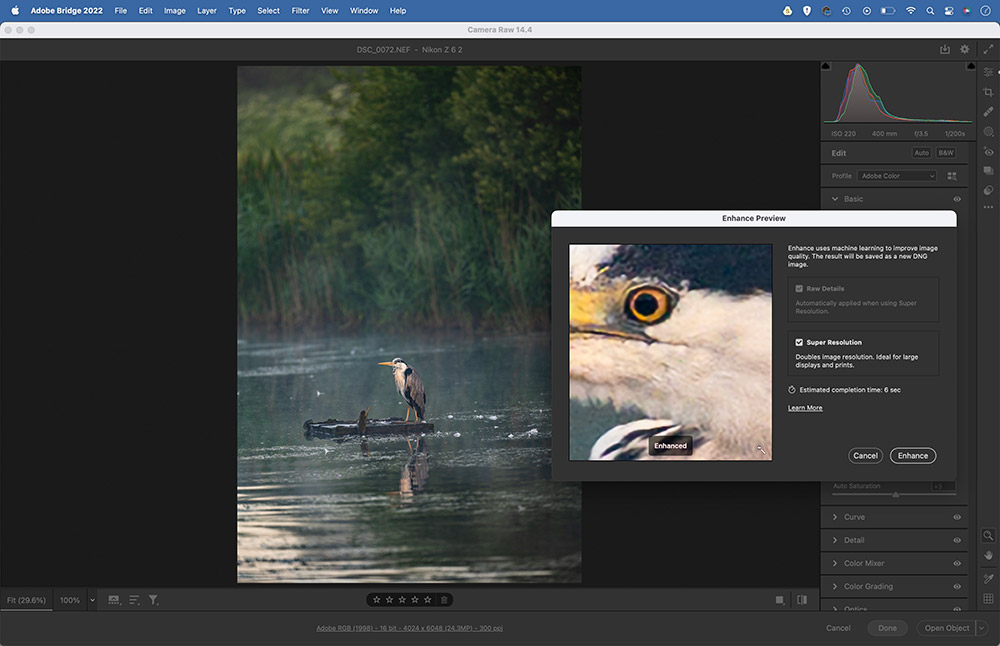

As for editing images, reputable contests and publications usually expect you to deliver a faithful representation of reality. Keep cropping to a minimum and only remove dust and reduce noise, or go in for some judicious sharpening. You should be okay with this – but read the competition rules or check with the editor first.

Learn from wildlife photography experts including Tesni Ward, Steve Winter and David Tipling on our AP Photography Holidays. You will have personal guidance and learn more about how to ethically photograph subjects on location and wildlife conservation.

See how others got on on our recent Costa Rica wildlife tour here.

Need guidance on how to take better wildlife and animal photos? See our complete guide to wildlife photography here, or have a look at our guide to animal photography.

Want to know what the best equipment for wildlife photography is? See the best cameras and lenses for wildlife photography.

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.