Hodge Close and Langdale Pikes from Holme Fell, Cumbria, by Joe Cornish. Sony a7R, Zeiss Sonar 55mm, 1/25sec at f/10, ISO 100. These images are published here with permission from Masters of Landscape Photography © published by Ammonite Press, RRP £25, Available online and from all good bookshops

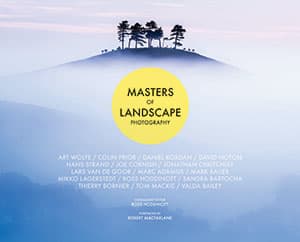

Pity anyone trying to come up with 16 masters of landscape photography to feature in an eponymous book, as there are so many great names to choose from across every continent. Fortunately, Ross Hoddinott and the rest of the team at Ammonite Press have pulled it off. Ross is a well-known landscape photographer in his own right, and recognises it was always going to be a subjective decision as to who would make the final cut.

‘Choosing who to feature in the book was very hard and let’s face it, anyone with a knowledge of this genre may well have come up with 16 different photographers,’ Ross tells AP from his studio in north Cornwall. ‘In the introduction, I make it clear that we are not saying the 16 photographers in the book are the “best” – this is just a selection. And there will always be a degree of bias in making that selection as it will be the photographers who inspire me, or whose style I like the most. Some iconic names will always spring to mind, but I also wanted to feature some less well-known photographers, who offer a different style.’

The idea for Masters of Landscape Photography came from Jason Hook, the publisher at Ammonite Press, for whom Ross has already written several books. Ross was on-board right from the start. ‘I loved the idea. I remembered seeing a similar book on the best landscape photographers when I was younger, and I thought there is nothing like this around at the moment. I saw Masters of Landscape Photography as an opportunity to explore different styles and attitudes, and mould them into a well-rounded book – not one biased to a particular style but one that was open to different interpretations and inspirations.’

Fairy Land of Zhejiang, Zhejiang, China, by Thierry Bornier. Phase One IQ280, Schneider Kreuznach 80mm, three seconds at f/14, ISO 50

Variety show

As this writer knows, trying to get visually oriented people to talk in depth about their inspirations and ways of working can be a challenge, but Ross reckons that everyone involved in Masters of Landscape Photography was very forthcoming.

‘It can be difficult getting people to answer questions in detail, but everyone liked the concept behind the book. Much of the credit also has to go to the editor, Rob Yarham, who came up with some great questions. Even allowing for the usual headaches you get in book publishing, I think the whole project came together relatively easily.’

Flicking through the book, it’s refreshing to see a variety of creative responses to the landscape, and there is a lot more here than by-the-numbers scenes of long-exposure water taken at the golden hour with the obligatory wet boulder in the foreground. More abstract and impressionistic approaches are also featured, which was a conscious decision on the editors’ part.

Hollywell Bay, Cornwall, by Ross Hoddinott. Nikon D810, 17-35mm, five seconds at f/11, ISO 64

‘We are seeing different ways of capturing landscape, so I was keen to include Valda Bailey and Sandra Bartocha, for instance, who are very creative in their approach,’ Ross explains. ‘With a book like this, you can’t please everyone. Some will like the more experimental styles, others will prefer a more “classic” landscape approach. The less conventional approaches won’t appeal to everyone, but I think it is good to highlight the more abstract, impressionistic styles, which we are also seeing in wildlife photography.’

And as Ross notes, deliberately breaking the perceived orthodoxy can become an orthodoxy in itself. ‘In photography there are always trends. I have always wanted to enjoy the kind of pictures that please me and not be too influenced by what is fashionable. Certainly, there are photographers at the moment who are shunning classic landscape approaches, but I still enjoy taking those kind of pictures. So I’d urge readers to take photos that please them, rather than worrying about outside viewpoints. And yes, there is a risk that by not conforming you are just conforming to something else anyway.’

Fearless, by Marc Adamus, showing the Grand Canyon in Colorado. Nikon D800, 14-24mm, 1/10sec at f/14, ISO 32

Adapt or die

While some names in the book will be less familiar to AP readers, there are a quite a few of the usual suspects, such as Joe Cornish and Art Wolfe. Ross doesn’t see featuring such well-publicised old hands to be in any way predictable or problematic.

‘The more established photographers are not just included because their photography is excellent, but because this is a tough profession. If you look at people like Joe or Art, you can see how they have coped with all the changes in the industry and they are still there, so big credit to them. Whether there will be a new generation of iconic names in 10 years’ time I don’t know. Nowadays, there are so many people doing photography to such a high standard that it’s difficult for anyone to make a significant name for themselves and stand out in the way that Joe or Art did. Maybe I can come back to you in 2028?’

The box on the below gives a taster of some of the sage advice in the Masters of Landscape Photography book, and each photographer emphasises different things in their engrossing and informative interviews – yet Ross reckons there are unifying themes emerging from the book.

‘In terms of technique, I was amazed at the diversity of the advice. You have David Noton on one page saying he wouldn’t want to spend more than four or five minutes processing a picture, then you have Marc Adamus saying he can spend hours on it, or Valda Bailey shooting at f/32 while everyone else is trying to avoid diffraction. I suppose the one big theme to emerge is just how challenging landscape photography has become as a profession.

Rapids, Abisko River, Lapland, Sweden, by Hans Strand. Hasselblad H3DII-50, 210mm lens, one second at f/16, ISO 50

Inevitably, you have to compromise in order to make money at the moment. To make a living from landscape photography is a very different thing from going and taking great images. There are ongoing challenges and pressures to write more; do more talks, tuition and workshops; and there is a worry that this pressure will start to stifle creativity in the long term.’

Indeed, Ross reckons that landscape photography as a purist career is dying fast, if not dead already. ‘If you define being a professional landscape photographer as just taking photographs then I think it’s probably impossible in 2018,’ Ross muses. ‘But if you define it as making a living from activities that relate to landscape photography, such as talks, books and articles, then it’s hard but still feasible. I was lucky in a sense, as when I turned professional, stock image revenue was already shrinking. So I never expected to travel the world and make money from selling the images, and I always thought I would have to do different things to survive. A lot of big stock photographers have seen the industry change massively, but you have to diversify or you don’t survive.’

Sunset over opium poppies, Durweston, Dorset, by Mark Bauer. Fujifilm X-Pro2, 10-24mm, 1/6sec at f/16, ISO 200

[breakout]

Advice from the masters

Just a few of the standout tips from Masters of Landscape Photography

Colin Prior

‘Depth of field is an illusion. Remember, we are looking at pixels on a page or screen and one of the challenges to becoming an authoritative photographer is in being able to create the illusion of three-dimensionality. It goes beyond small apertures… It is fundamentally the ability to read the three-dimensional world in which we live and understand how it will translate into the two-dimensional world of photography.’

Daniel Kordan

‘I’m in constant search of light and strong compositions. On the one hand, the idea for a composition should be clear and simple, and on the other, I prefer to have complicated three-dimensional scenes with a distinctive foreground, which is balanced with the other elements in the image. I use strong perspective, rhythmical perspective and visual paths in my photographs, while trying not to lose the sense of scale.’

Hans Strand

‘I never use filters nowadays. If a sky is too bright in relation to the landscape, I simply make an extra 2-3 stop exposure and blend it in with the exposure of the landscape at the processing stage. This way I get seamless and natural looking transitions between the land and sky, in a way you never get by using graduated filters.’

Sandra Bartocha

‘If I were to have to decide which piece of kit is the most important to me, then I would probably say my Nikon D810 and the Nikkor 80-400mm lens. That combination gives me a huge range of opportunities to capture the landscape and details in an intimate way.’

Joe Cornish

‘No place is a photographic cliché. The only clichés are the overused, mindless and derivative approaches used in making pictures of these places… Photography’s problem is that it is both descriptive and easy, and apparently sophisticated appearances can be achieved effortlessly, especially with a phone camera and apps. I believe in individual seeing, the possibility of a relationship with the landscape, and the unique circumstances and conditions of each encounter. However familiar a place, it is possible to retain a certain innocence, so that each time we see it anew.’

Tom Mackie

‘If I had to use only one filter, it would be a polariser, as it helps to remove reflections from foliage, increase colour saturation and make clouds pop out against a deep blue sky. I love the effect that ND filters, the Lee Little Stopper, Big Stopper and Super Stopper, can achieve with moving clouds, smoothing out water to improve reflections and creating motion blur in moving subjects such as flowers.’

Ross Hoddinott

‘I’m really not a very technical photographer. Ultimately, sound technique is essential to consistently capture the images you previsualise. However, I still don’t obsess about technique, the gear I use or over-processing my images. For me, the creative aspects of photography are most important – vision, use of light, composition and creative interpretation, for instance. These are the things that will define your images and make them standout. Being technically adept alone will not get you very far in a creative industry such as photography.’

Lars van der Goor

‘You need some pleasant light to start with, in order to get a more dreamy look. Also, fog is a perfect ingredient for adding a dreamy feel to an image. Using a shallow depth of field is another way. By focusing on the first trees, for instance, in a tree-lined alley, you will have that nice paint-like blur in the background.’[/breakout]

Masters of Landscape Photography is available now from Ammonite Press for £25, ISBN 978-1781453209. See the website at

Masters of Landscape Photography is available now from Ammonite Press for £25, ISBN 978-1781453209. See the website at