All images by Paul Gallagher. Reynisdrangar, Iceland. ‘The pillars in the sea came and went with the passing cloud,’ says Paul. ‘The main challenge was the sea spray building up on my filters’

Paul Gallagher believes that one of the most exciting things about being a photographer is to re-invent yourself, or at least to allow yourself to develop. ‘As a photographer, you’ve got to do that,’ he says. ‘I look at images I took ten years ago and I wouldn’t put them on my wall now. I’ve left that point behind and moved forward. Change gives you the stimulus to continue exploring.’

Paul speaks as someone whose landscape photography has undergone a number of changes during the past few years. He was a confirmed film user who moved to digital capture; a large-format camera enthusiast who downsized to a DSLR; and an exclusively black & white photographer who changed to shooting in colour.

However, some things don’t change. He still loves photographing wild and remote landscapes, and he continues to shoot with the same fastidious attention to detail as he did in his large-format years.

Paul became a photographer almost three decades ago, after studying graphic design and photography at Southport College, Merseyside. Afterwards, he worked as an assistant in a commercial studio in Liverpool, where he began using an MPP 5x4in camera for architectural work and product shots. He took to the format immediately, loving the precisely engineered equipment, the methodical process and the outstanding quality of the results.

Paul also used 5x4in kit for his personal landscape work and predominantly concentrated on the landscapes of northern England and Scotland, later using a hand-made Walker Titan XL. During the 2000s, while digital kit grew massively in popularity and came to dominate photography, Paul opted to stay with the high-quality traditional methods he loved using. He dabbled in digital with a Nikon D700, but 5×4 was still king.

That all changed in 2012, when the 36.3-million-pixel Nikon D800E was released. For Paul, this camera was a game-changer.

With the camera on the boardwalk edge, Paul got the diagonals he needed with the steel beams pushing out into the reflected clouds

New era

‘Even after using 5×4 for so many years, I found the quality of the images produced by the D800E was astounding,’ Paul says. ‘Until then, nothing came close, but I could instantly see that digital had reached a point where it was as good as – or better than – 5×4 film.’

While Paul’s large-format kit gathered dust, he started going on shoots with his new, 50% lighter kit bag. However, old habits die hard, and although the camera offered a range of state-of-the-art, hi-tech functions, Paul proceeded to cheerfully ignore most of them.

‘To be a large-format photographer is to be completely and utterly fastidious, and to have a systematic approach to everything,’ he says. ‘That has to become second nature, or you’re not concentrating on what you’re photographing.

‘As soon as I got the D800E, I put it entirely on manual, so I could have full control over the exposure and aperture settings. I set it at ISO 100 for maximum quality and only shot raw files. In other words, I used exactly the same approach and methods I used with 5×4. I use the same process now and still shoot no more than 20 images a day.’

‘The ice in this Iceland lagoon is in a constant state of flux. The blues are astounding,’ says Paul

Transition to colour

Although Paul had used black & white film almost exclusively for many years, moving to digital encouraged him to incorporate colour in his images. Previously, he thought colour was an unnecessary addition to images and had a particular dislike for Fujifilm Velvia.

‘I only ever shot ten sheets of Velvia in my professional career,’ he says. ‘I remember looking at the images and thinking the colours were so gaudy and saturated. I really didn’t like it and I was one of the few pros who didn’t shed a tear when Velvia was discontinued. I shot negative film on the rare occasions I shot colour, because the colours were so much more muted.’

However, digital capture made Paul completely reassess his attitude towards colour.

‘As I was starting to shoot with digital platforms, rather than black & white film stock, my benchmark then was a raw file and full colour. I got to a stage where I was looking at raw files and thinking, do I really need to remove the colour? Maybe I should start exploring the colour information. So I started slowly and gingerly experimenting with leaving the images in colour.

‘I think going from colour to black & white is a difficult process because you’re removing something that you’re used to seeing in real life. However, going the other way, from black & white, in which I’ve just used form, line, texture, tonality and luminosity, was very different. I could still use the same recipe, if you like, but I was just allowing myself to add a little more spice and seasoning to the ingredients.’

‘This shot was taken just after a blizzard in Lofoten,’ says Paul. ‘There was another storm imminent, hence the black skies. I had to work fast’

New landscapes

In addition to the technical changes in Paul’s work, he also started exploring landscapes beyond his beloved north of England and Scotland. He was particularly drawn to the austere beauty of Lofoten in Norway. The mountainous archipelago, located inside the Arctic Circle, and its muted colour palette, mainly consisting of blues and greys, was ideal for Paul to explore his use of colour.

‘In the Lofoten environment, moving from large format to DSLR and from black & white to colour, all came together,’ he says. ‘The landscape is similar to Iceland and it’s predominantly coastline, but the quality of light is quite different from Iceland.’

Although he visited popular tourist areas, Paul couldn’t wait to get as far away from them as possible.

‘I’m not one for shooting the obvious subjects, so when I first went there, I got a road map and just explored tiny back roads and dirt tracks, and often ended up somewhere very remote. This made me feel very isolated, but it also allowed me to soak up the place.

‘I did go to the famous places, such as the village of Reine, and they are absolutely beautiful, but I was always drawn back to somewhere that was off the beaten track. It’s a really fascinating place and the weather changes all the time, radically transforming the appearance of the landscape. If you braved the worst weather and got breaks in the blizzards, the landscape and environment came into its own fantastically well. It was absolutely staggering.’

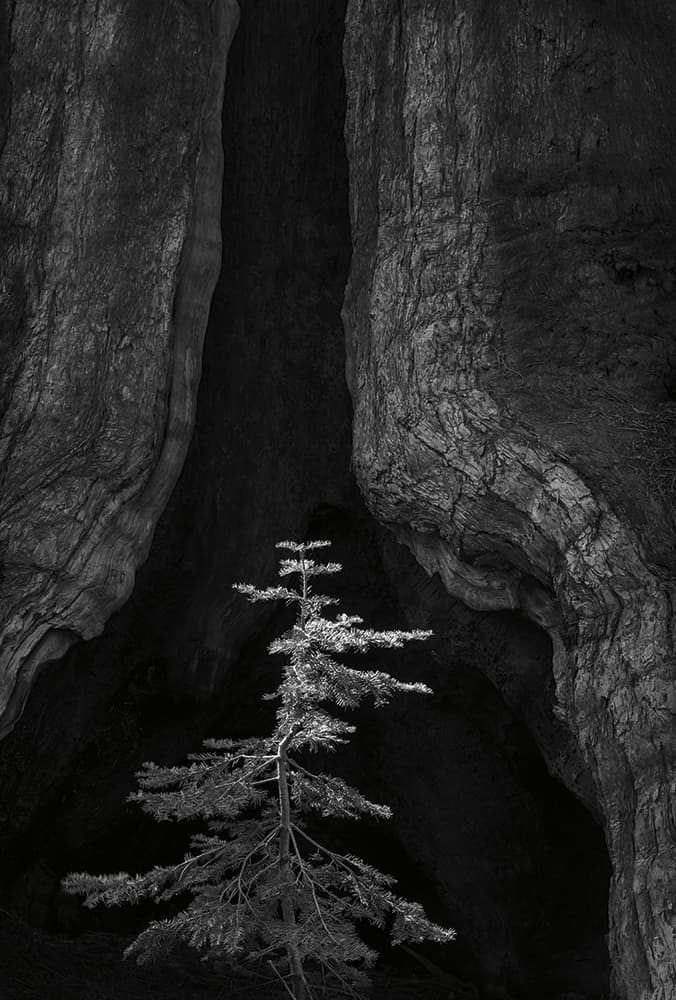

The last light of the day, with the contrast of the yellow leaves on the smaller trees against the darker tones of the pines

Paul’s Lofoten images, some of which are featured on these pages, show that the introduction of colour has done nothing to lessen the impact of his work. Deserted, ice-strewn beaches, rocky outcrops, distant mountains and stormy skies predominate in images that are both technically accomplished and emotional, and which distil the essence of these remote locations.

This portfolio of work has been very well received and marks the beginning of a new and productive period in Paul’s photography. He continues to shoot black & white as well as colour, but now feels comfortable using both.

‘For me, this period has been about allowing my work to naturally evolve, but not to force it,’ he explains. ‘I just decided to try it and I’m very excited by the results.

‘I think that if you do it that way, your work still retains its visual signature. You’re still shooting the same kind of image, but with a little bit of icing on the cake. My aim is that my work will continue to evolve as time goes by. Heaven forbid that I’m still doing the same things in 15 or 20 years’ time.’

Perspective control

Paul explains how a tilt-and-shift lens aided his new digital approach

When Paul moved to digital, the one thing he says he could not do without was the camera movements on a 5×4 that allowed him to alter the plane of focus and achieve front-to-back sharpness in his images. However, he found he could achieve similar results by using the Nikon PC-E Nikkor 24mm f/3.5D ED lens.

The perspective control (or tilt-and-shift) lens allows you to tilt the front of the lens forward, enabling you to alter the plane of focus. If you turn it through 45°, the ‘tilt’ function becomes ‘swing’, which allows you to alter the plane of focus from side-to-side. The tilt-and-shift is often regarded as a lens for architectural photography, as the movements also allow the user to correct converging verticals in-camera.

‘Regardless of what it says on the label, I wanted to use the “tilt” function of the lens function for my landscape work,’ says Paul. ‘I’d used tilt in virtually every landscape I’d ever done and felt handicapped without it. However much you stop down a conventional 24mm lens, you can’t get the degree of sharpness throughout the image that’s possible with a tilt-and-shift lens. It’s just physics.’

The 24mm PC-E lens remains Paul’s main workhorse lens. His other lenses are a 70-200mm f/2.8, which he mainly uses for woodland shots, and a 16-35mm f/4, which he specifically bought for photographing the northern lights in Norway. Generally, Paul avoids using zoom lenses. ‘I firmly believe that the best zoom lens is your legs,’ he says.

Paul is one of the UK’s leading landscape photographers. He has produced two books of photographs, Aspects of Expression (2008) and Chords of Grey (2010). A new book on infrared photography will be published later this year. He regularly runs tours and workshops through his company Aspect2i (www.aspect2i.co.uk). To see more, go to www.paulgallagher.co.uk