The first survey exhibition of photographer Annabel Moeller, whose 30-year career has chronicled the human condition and perseverance in its many manifestations, is now on display at Farleys House & Gallery in Sussex until July. Jessica Miller spoke with Annabel about her career defined by adventure, curiosity, and diverse subject matters.

This Spring, Farleys House & Gallery – the post-war Sussex home of Lee Miller – is the base of Annabel Moeller’s first survey exhibition. Comparable to the multifaceted but fascinating work of Lee Miller herself, Annabel covers a range of genres including war and conflict photojournalism, performing arts, interiors, and portraiture. From major productions around the world, including opera, ballet, and fashion events, through to her documentation of current affairs, conflict and its aftermath, the exhibition presents an extraordinary catalogue of human experiences.

Early years

Annabel’s career to date spans 30 years, with her photographic journey truly beginning when she went to Australia on holiday. But her inspiration started much earlier as her father was working on Fleet Street, a major street in London known for publishing. “I was always seeing him and all his mates having loads of great adventures and all the fun of the fair that comes with that,” she reflected.

When Annabel left school, she went to study a business management course at the London College of Fashion. Having discovered that it was the wrong course – and a 9-5 job not being suitable for her to thrive – she landed a job at Camera Press, one of Britain’s top picture library agencies. “I’m going to take pictures and have every adventure going, if I can,” she told me, “Getting into photography just suited me personality wise, as well as creatively.”

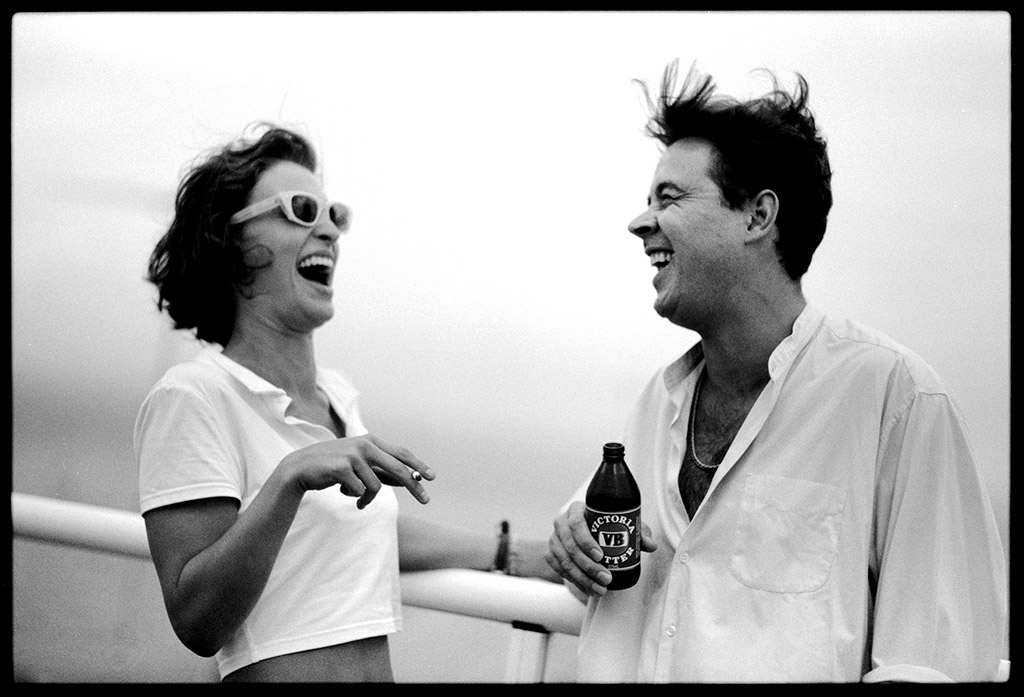

She then went on a short trip to Australia – which ended up lasting 16 years – where she worked for a photographer in a commercial studio. Since she didn’t go to college or university to learn about photography, it was here she learnt everything about darkrooms and processing film.

Bondi Beach Surf Scene, Sydney, Australia 1990s. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

Diverse subjects

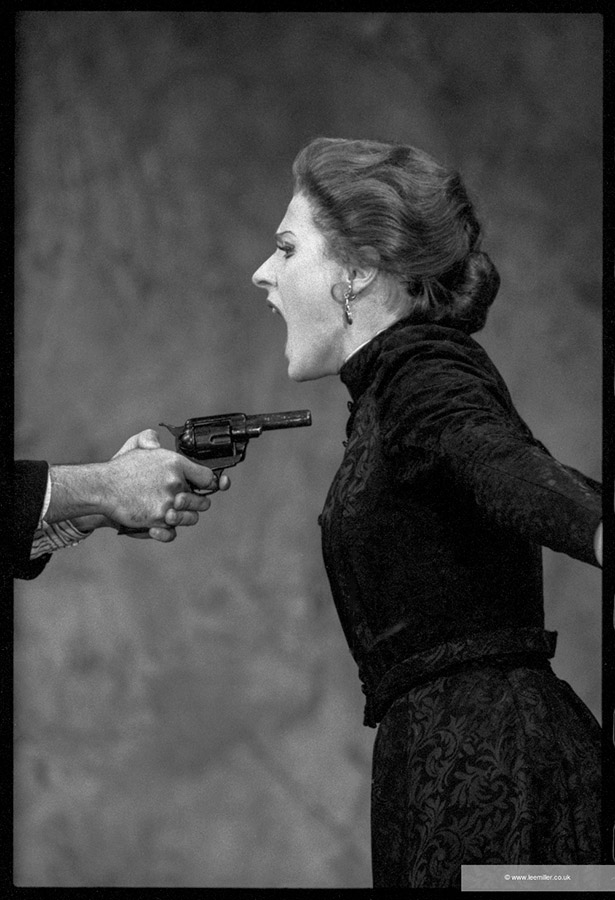

The exhibition, and book made alongside it, doesn’t nearly cover the whole 30 years. Rather, it just gives the viewer a glimpse. Arranged thematically, it starts with a candid look at life in Sydney and Annabel’s early works of her friends, taken in the 90s, before the work created at Opera Australia. Highlights include an image from director Lindy Hume’s critically acclaimed, feminist telling of Carmen in 1995, showing Suzanne Johnston as the titular character, with a disembodied gun pointed at her chest.

Suzanne Johnston as Carmen , Carmen, Sydney Opera House, Australia 1995

Composer: Georges Bizet, Director: Lindy Hume. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

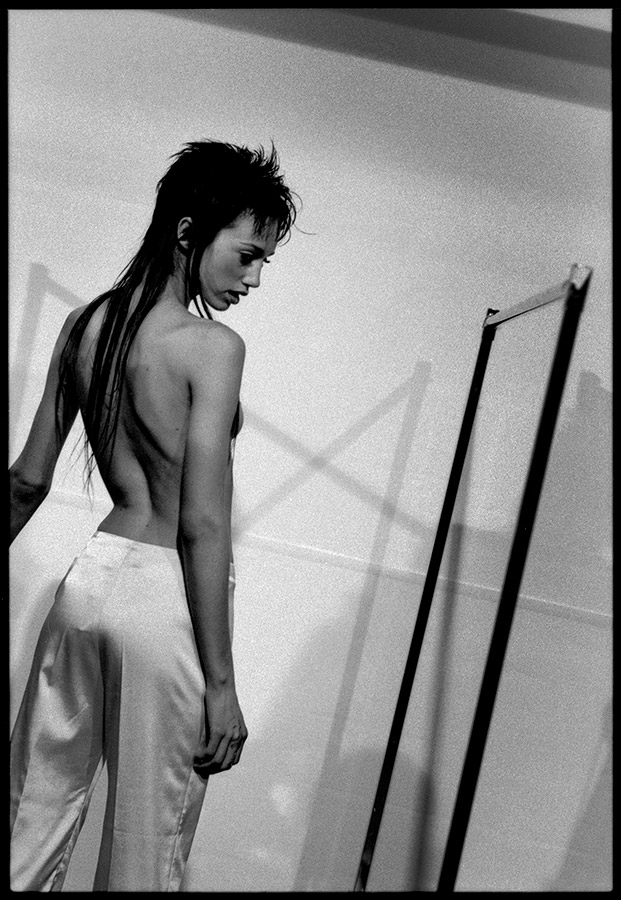

Also on display will be a selection of images from when Moeller covered the first few iterations of Australian Fashion Week, which began in 1996, including dramatic shots of the catwalk and the backstage crews, demonstrating the physical reality of its fast-paced events.

Look at Me, Australian Fashion week, Sydney, Australia c1996-1999. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

Annabel succeeded in lifting the lid on the world of ballet during her time spent photographing prominent performances of the English National Ballet from 2007-2012. With resulting images revealing the raw power and grit that lies behind the beauty and apparent effortlessness of the dancers’ performances. Photographs included will highlight intimate behind-the-scenes moments from the ballet, such as a ballerina rehearsing in the wings of the London Coliseum during the Ballet Icons performance in 2017.

Ballet Icons, backstage at London Coliseum, England 2017. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

In contrast to her earlier work, the exhibition moves into the documentation of war, conflicts, and their aftermath. Moeller was embedded with British troops during their last tour of duty in Iraq in 2009. She also visited Somalia in 2015 with a small media team to document the ongoing violence and instability, with the report balanced by more positive aspects of life there. The team consisted of Annabel alongside television journalist Rageh Omaar, cameraman Mo Dahir, stills photographer and facilitator William Oswald.

Close Protection out front, Media visit, Mogadishu, Somalia 2015. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

A first for everything

This may come to some surprise, but Annabel’s exhibition at Farley’s will be her first ever gallery show of her work. She has also never had a motive to share her work in an exhibition. “My work has been on posters and all that. So that’s kind of enough to feed that little monster.” So why now? Well it was somewhat thanks to one of the most remarkable female icons of the 20th Century, Lee Miller…

“Back in the day, when I was at Camera Press in the late 80s, quite suddenly I found myself standing outside a window display containing the assembled belongings of someone who was patently yet unimaginably glamorous and adventurous. This was my first introduction to the force of nature that was Lee Miller. There in the window, a mannequin dressed smartly in her army fatigues, surrounded by assorted belongings: cameras, rolls of film, a case of wine, black & white photographs, jewellery and more.”

Having started out as Man Ray’s apprentice and rubbing shoulders with other Surrealist icons, Lee Miller soon became a fashion and fine art photographer in her own right, before going on to be a war correspondent for Vogue. The book The Lives of Lee Miller, written by her son Antony Penrose and first published in 1985, covers her multidisciplinary career. “The book was almost permission. You don’t have to just be a fashion photographer, or just this or just that. You can have variety. Her whole ethos seemed to be just jump in and cover it all.”

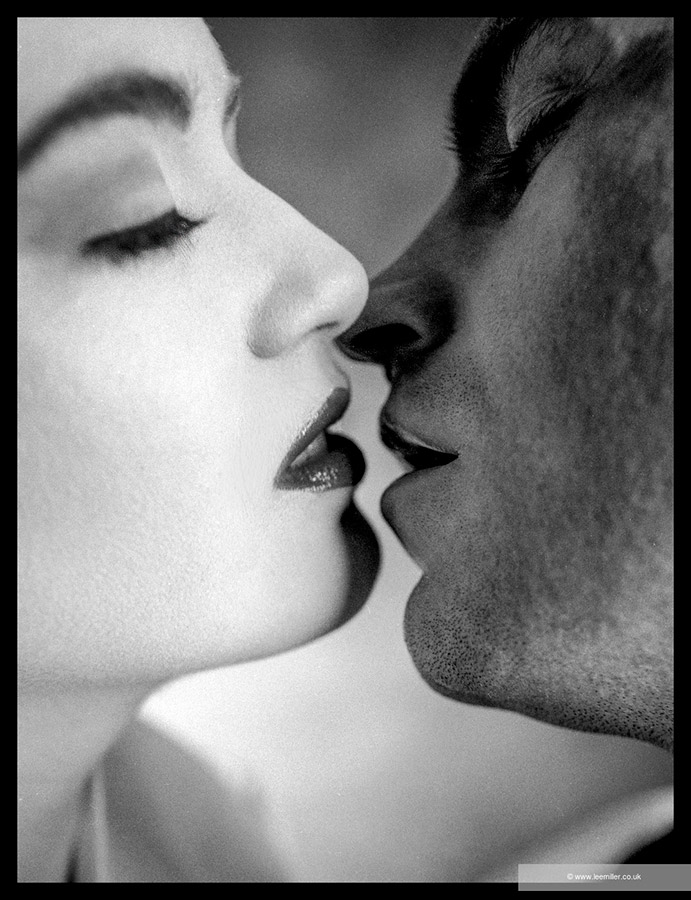

Madame Butterfly, Promotional image for Opera Australia Season brochure, Sydney Opera House, Australia 1998 Composer: Giacomo Puccini. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

“My mum was always sending me paper clippings on the latest exhibition on Lee Miller and she was always in the back of my mind. Many years passed after discovering the book and I got back from Australia, but even so years later – only about five years ago – I suddenly realised that Farleys existed, and that Tony (Penrose) and Ami (Bouhassane) [Lee Miller’s granddaughter] existed. I hadn’t thought that her family could be around still. So, I raced down and went on a tour of the gallery that Tony and Ami were doing. At the end Tony said, here’s the book. I told him, ‘I don’t need to buy that book. Because I bought that book when it first came out. It’s got your signature in it.’ I then told him my story, that I had done a bit of this, a bit of that. I mean, obviously nothing like on the scale of Lee.”

Covid put a halt to some interactions with the gallery but they stayed in touch. One day Ami suggested that Annabel have an exhibition in the new gallery space. “I thought, have all my Christmases come at once!? That’s a joy,” she said.

Annabel Moeller: Friends to Frontiers exhibition preview at Farleys House & Gallery. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

Annabel’s motivation

On paper the range of subjects that Annabel has covered throughout her career are individually challenging. How do you go from photographing ballet to following troops in Iraq and Afghanistan?

“My whole motivation for being a photographer is for the variety of everything. For the intellectual stimulation and the emotional rewards for just being curious. I have absolutely no trouble going from one to the other, just get excited about it.

When I first started shooting the ballet, there was a bit of nervousness in there because I had to get my shutter speeds right – when you haven’t done it before, and people are expecting results.

Whereas, say, Afghanistan or Iraq, my main problem there for instance was that everyone I was travelling with already knew everybody. You had to bide your time a bit to get to know everyone yourself. You’re there for a week and if you just start taking photos of them, they could suddenly feel like some Disney characters.”

Scanning the horizon between Basra and Umm Qsar sea port, Iraq 2009. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

“I am open to everything with such a genuine curiosity and a sense of adventure that they’re all quite separate. Every time you pick up your camera, or just the fun of getting on a plane and landing somewhere you’ve never been before. It’s that feeling, isn’t it?

But when I think of ‘challenging’. It’s never the warzone. So, the time that I photographed the state opening. You cannot come back without a picture. You’ve absolutely got the nerves. That’s the main challenge, all that work stuff in London is where I get them for example, not Afghanistan.”

Buzkashi horses training in the Panjshir Valley, Afghanistan 2012. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

From film to digital

Throughout her career, Annabel has not only experienced changes between subject matters and project commissions, but also the impact of digital. Having started shooting with a Nikon film camera, and only shooting film, perhaps the largest challenge of her career has in fact been the introduction of digital photography.

“It was absolutely seismic. At one point I had a client say, ‘we can’t book you’. They wanted me to get a digital camera. And then with that came a computer, and then Photoshop, but none of us my age knew anything about that.

I’ve always shot Nikon and now I shoot Z series which are mirrorless, nimble and silent. Now the clients say, you can’t shoot unless you’re on silent. For instance, the Queen’s funeral or any speeches in the Palace of Westminster or any kind of corporate events. They’re basically a computer with a lens on.”

“I remember when we shot the ballet, there were 10 photographers at the final dress rehearsal. Every time they pointed their toe beautifully, 10 cameras were going off like machine guns” Annabel laughed. Despite some challenge along the way, she does see the benefit, “the creative freedom with digital is enormous, because you can see that you’re getting the shot as you’re doing it. You also have more financial freedom. Every shot you took before with film cost you money every single time you click the camera, that was the thing.

If I had one day at Fashion Week, your client’s got a budget. They’ve got 20 rolls of film, maybe 10, so you had to make sure that lasted you all day. I can’t imagine worrying about that now. But you did and you coped, and it was reasonable. You shot one thing at a time.”

When it comes to what one thing you chose to shoot, you did it carefully. It was so obvious at the time. At Fashion Week for example, my brief was to just keep capturing the atmosphere. You just look, sit there carefully, and wait for the scene to unfold. As Bresson said, it’s that decisive moment.”

Elena Glurdjidze as Odette, Swan Lake, London Coliseum, England 2009. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

When shooting film, you wouldn’t know how it looked for two days, until it came out of the lab. There’s a lot of stress involved for you and the client with that. You had to really know what you’re doing. In fact, you wouldn’t go to a job unless you knew you were going to expose it correctly.

The other thing that I would say is you’d take the film to the lab, go home, and put your feet up. Nowadays, clients practically want the pictures before you take them. You come home to hours of post-production and editing. But you have total control of it. It’s like a completely different job almost.”

Julie, Australian Fashion week, Sydney, Australia c1996-1999. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

Annabel’s favourite projects

Having experienced so much over the last 30 years, you would expect one or two projects that stand out. “Ballet was an ongoing commission. But working with those dancers was utter joy because they’re so beautiful and disciplined.” But for Annabel, there are two others that stay very close to her heart.

In 2011, Annabel began a series of trips to Afghanistan, with the charity Afghan Mother and Child Rescue run by veteran British Army officers Brigadier Peter Stewart-Richardson and Major Roddy Jones, to photograph the setting up of maternity clinics in the majestic Panjshir Valley. “Because I got to know everybody. It was such a stunning place and so much going on. But it was also tough, as you’re dealing with people that have seen a lot of bad, so you have to be very careful and respectful.”

“My work with David Nott is also extremely close to my heart – it’s very special, and important.” Since 2018 Annabel has been working with the David Nott Foundation, a humanitarian organisation dedicated to training doctors and surgeons working in conflict, witnessing first-hand the ability for bodies to be repaired in incredibly challenging environments.

David Nott in shelled hospital outside Kharkiv, Ukraine 2022. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

David Nott is a vascular and trauma surgeon whom Annabel has travelled with to areas of conflict and instability to document the work of his foundation. This moving image was taken last year of David in a shelled hospital in Kharkiv during the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Despite not being able to discuss upcoming projects and commissions just yet, it’s safe to say that Annabel’s career continues to flourish, and we’re excited to see where her adventures take her next.

Dr Aiya Z Saiah Kama, DNF Misrata, Libya 2018. Intimate portraits of female surgeons in Libya taken in 2018 reflect Moeller’s propensity for close observation, allowing for a deeper connection with her subjects. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

Annabel Moeller’s Top Tips for starting out in photojournalism:

- Just do it – Don’t be afraid to just jump in. Start with something small, it could be just documenting your local park.

- Manual, Manual, Manual – The camera can make mistakes too, always shoot in manual and take control.

- Look around at your environment and set up so you are in a good place exposure-wise.

- Keep watching and have your wits about you. You should be immersed in what is happening around you and what you are doing – not thinking about what you are going to have for tea.

Building a portfolio

In terms of building up a portfolio, Annabel suggests bringing all your favourite photographs together as a starting point.

- If you work with a range of subjects start with your “best of” selection, narrowing it down to 5-10 photos.

- Ask for other people’s opinions on them and what photos they’d include or remove. As a photographer you are too close to your own work. Sometimes you can’t see what the good stuff is.

Annabel Moeller: Friends to Frontiers exhibition

On now until 2nd July 2023

Open Sundays and Thursdays 10am-4.30pm

The book, Annabel Moeller: Friends to Frontiers, is also now available to purchase here.

www.farleyshouseandgallery.co.uk/exhibition-detail/friends-to-frontiers/

Instagram: @farleyshg

Annabel Moeller: Friends to Frontiers exhibition preview at Farleys House & Gallery. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

Instagram: @annabelmoellerphotography

Find more of the best photography exhibitions to see in 2023.

Featured image: Ian Reid, Australian Fashion week, Sydney, Australia c1996-1999. Image credit: Annabel Moeller © Lee Miller Archives

Further reading:

Best cameras for photojournalism and documentary in 2023

Open call: Women Photograph grants for documentary photographers

Opinion: We need great photojournalism more than ever

University of Gloucestershire students share new perspectives at photojournalism show