In the late 1970s, Olympus launched the XA range of ultra-compact 35mm cameras, followed later by the Mju family. John Gilbey looks at what they still have to offer.

To the photographer of the 1970s, the Olympus camera brand was almost synonymous with miniaturisation. The Olympus OM1 single lens reflex, introduced in 1973, had shrunk the size of a standard 35mm SLR by about a quarter leaving other brands racing to catch up. Rangefinder cameras such as the Olympus 35RC were gaining a strong following among travel and adventure photographers for the same reason.

Despite, or perhaps because of, these developments there remained an almost untapped market for even smaller cameras. Many aspiring photographers who had started with something like a Kodak Instamatic 126 camera were looking to graduate to a more versatile and capable alternative. To satisfy this need, Olympus developed an interesting series of ultra-compact 35mm models based on a novel clamshell design, which could slide into a pocket and become truly “go anywhere” cameras.

The Olympus XA series

In 1979, the original Olympus XA was launched, and it was immediately obvious that this was something rather special. Despite its compact format – Olympus called it a “capsule camera” – it was a fully-featured 35mm rangefinder camera with aperture-priority automatic exposure and a number of other offerings which made people sit up and take notice.

Olympus used plastic materials in the XA to a much greater extent than in previous designs, utilising the flexibility in design and manufacture which this offered. The sliding clamshell panel which protects the lens when not in use is the most obvious manifestation of this, and it gives the XA its characteristic look. In other areas, precision machined metals are still present, especially where this offers the opportunity for reducing the size or thickness of components. The camera back, pressed from thin but rigid metal, is a case in point.

The XA is powered by two SR44/LR44 button cell batteries, on which it is wholly reliant. Without them there is no manual backup, so it pays to keep a spare set handy. Having said that, the batteries supply power to the exposure meter, the shutter and not much else. So the lifetime of a set of batteries is very good, a year or more in normal use. Access to the battery compartment is via a coin-slot screw cover in the base.

Sliding the clamshell cover open reveals the protected elements of the camera – including the excellent 35mm f/2.8 Zuiko prime lens. This is an impressive “reverse retrofocus” design, where the lens-to-film distance is markedly less than the focal length. While this design is more complex than some traditional rangefinder lenses, it made it possible to keep the body of the XA surprisingly slim. In the early design stages, a simpler Tessar design was considered, but was rejected by the designers as it made the camera too bulky.

The chosen design has 6 elements in 5 groups, and offers coupled rangefinder focusing from 0.85m to infinity. There is a focus lever below the lens and a distance scale above it. The shutter is electronically timed and will run from about 10 seconds to 1/500th – allowing for low-light long exposures of moving water and twilight landscapes. The shutter release is a recessed “sensor” type which reduces camera shake, but there is no cable release socket.

Aperture is adjustable from f/2.8 to f/22 using a scale on the body, and the aperture itself is of the two-piece “diamond” type typical of automatic compacts of that period. Film speed is manually set, and can be between 25 and 800 ASA/ISO. As well as the rangefinder image, the viewfinder offers a bright-line frame to show the limits of the captured image. On the left hand side, a moving needle shows the shutter speed selected by the meter.

On the base of the camera is a small switch which offers backlight compensation of 1.5 stops, a self-timer function, and a battery tester which emits an electronic tone if the battery is healthy. There is no standard flash hot-shoe, but a dedicated flashgun can be attached with a captive screw to the end of the body – indeed a couple of versions are available with different guide numbers. While not as sophisticated as modern systems, this does a decent job of adding light to scene where there isn’t an alternative, and the location of the flash helps avoid “red eye” effects.

The back of the XA is opened in the traditional 35mm manner, by pulling up the film rewind knob, to reveal a fairly standard internal layout of film gate and pressure plate. Film is wound on using a ratcheted thumbwheel at the right hand corner of the body.

Over time, Olympus added some other versions of the XA to the range, but none matched the technical prowess of the original. The XA2, for example, is a much-simplified design, with zone focusing in place of the rangefinder and programmed exposure instead of aperture priority, which removes much of the creative flexibility of the XA. The XA4 launched in 1985 was interesting, featuring a wider 28mm lens and closer focusing. But again, it relied on zone focusing and programmed exposure.

The Olympus Mju series

As the 1990s approached, it was clear that the world was changing. The new technologies of autofocus and automatic film advance were rapidly becoming vital in maintaining and developing market share. Olympus answered these requirements in 1991 with the Mju series, which was called the Stylus in some territories such as the USA.

Slightly chunkier than the XA, but a good deal lighter, the Olympus Mju-1 employed a 100-step infrared autofocus system and motorised film transport in a much more sculpted body. The lens was still protected by a sliding plastic panel – one which operated rather more smoothly than the version on the XA – but a small LCD panel for frame counting and status indication had appeared on the top plate. The design employed plastics to an even greater degree, allowing the designers more freedom in the placement of various features. All the components of lens, viewfinder, autofocus and the new built-in flash were now protected by the sliding panel. Sadly, however, the 35mm f/2.8 lens of the XA had now become a less versatile f/3.5 version.

The shutter release had evolved slightly, with a good-sized button offering a more positive action than the sensor of the XA, while two smaller buttons on the top plate selected flash options and the self-timer function. With so much more automation, the Mju also acquired a power upgrade. In place of the button cells, a single CR-123 lithium or alkaline battery was required – and, once again, the camera is dead without it. The battery is housed behind a swing out panel on the right-hand end of the camera.

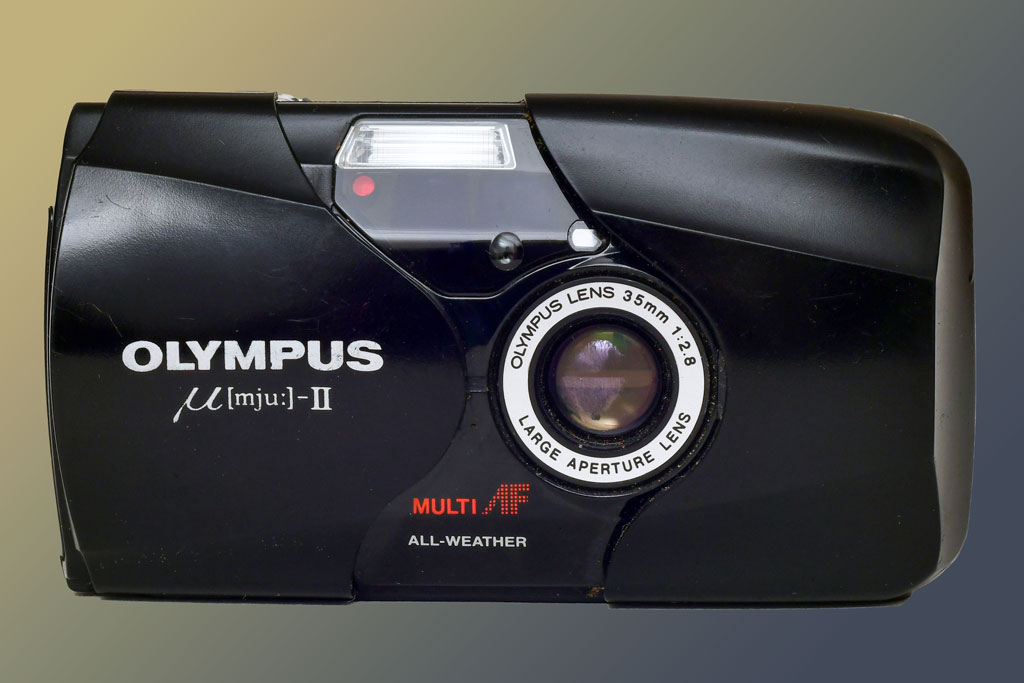

The Mju was very successful, with Olympus claiming sales of over 5 million worldwide. But to me it seemed like a stop-gap design, and lacked some of the unique charm of the original XA. Presumably, someone at Olympus was thinking along the same lines, because in 1997 they launched the wholly redesigned Mju-II – a dramatically improved offering.

Smaller and thinner than the original model, the Olympus Mju-II offered an upgraded multi-autofocus system, a more sophisticated flash support and restored the 35mm f/2.8 lens, which focused from 0.35m to infinity. The small LCD screen had migrated to the rear door of the camera, with buttons below to select delayed action and flash mode – which included red-eye reduction settings and a night-mode to allow “slow sync” long exposures with flash. Shutter speed and aperture were programmed, with no viewfinder information other than “flash ready” and “slow shutter speed warning” LEDs. Shutter speeds reportedly ran from 4 seconds to 1/1000sec, but I have measured exposures rather longer than that. The aperture of the 35mm lens, which was made up of 4 elements in 4 groups, was between f/2.8 and f/11.

The body of the Mju-II tapered almost to a point, making it very easy to slide into a pocket. This feature is explained when you open the back of the camera, as the 35mm film was designed to run in the “wrong” direction – from right to left – with the cassette being held on the right-hand side of the body. Loading is automatic and, in my experience, very reliable – with the film transport being rapid and very quiet. Rewind of the film into the cassette is automatic, although – as with the original Mju – there is a button to rewind a film part of the way through a roll.

The Mju-II was a sophisticated and highly developed offering, and I have a couple which I still use regularly. It is no surprise that Olympus sold over 3.8 million of them, despite it being part of a highly competitive marketplace.

Along with the Mju and Mju-II, Olympus produced a number of similar cameras with zoom lenses, to match the new market demands for versatility. Unfortunately, these models sacrificed some of the compactness of the originals and had much smaller maximum apertures, relying instead on the new, faster and sharper colour negative films to make up the difference. The Mju and Stylus brand names survived well into the digital era, but few of these offerings had the style or longevity of the film originals.

Olympus XA vs Mju – In the field

Both the XA and the Mju – especially the Mju-II – ultra-compact 35mm cameras are supremely portable and effective tools for capturing the unexpected image, or for use in situations where it does not pay to be conspicuous in your photography.

I suppose I should confess at this point that I once bought an additional Mju-II because I was convinced I had lost the original one. A few months later, I found the one I’d lost in the phone pocket of my walking jacket – it really is that small and light! Mind you, having a spare one of these delightful compacts is never a problem, as it offers you the chance to have a camera in each pocket, one with high-speed black and white film for action, the other with slow colour transparency film for landscapes. This gives you great versatility with a lot less fuss than, say, a couple of 35mm SLR bodies, even Olympus OM1s!

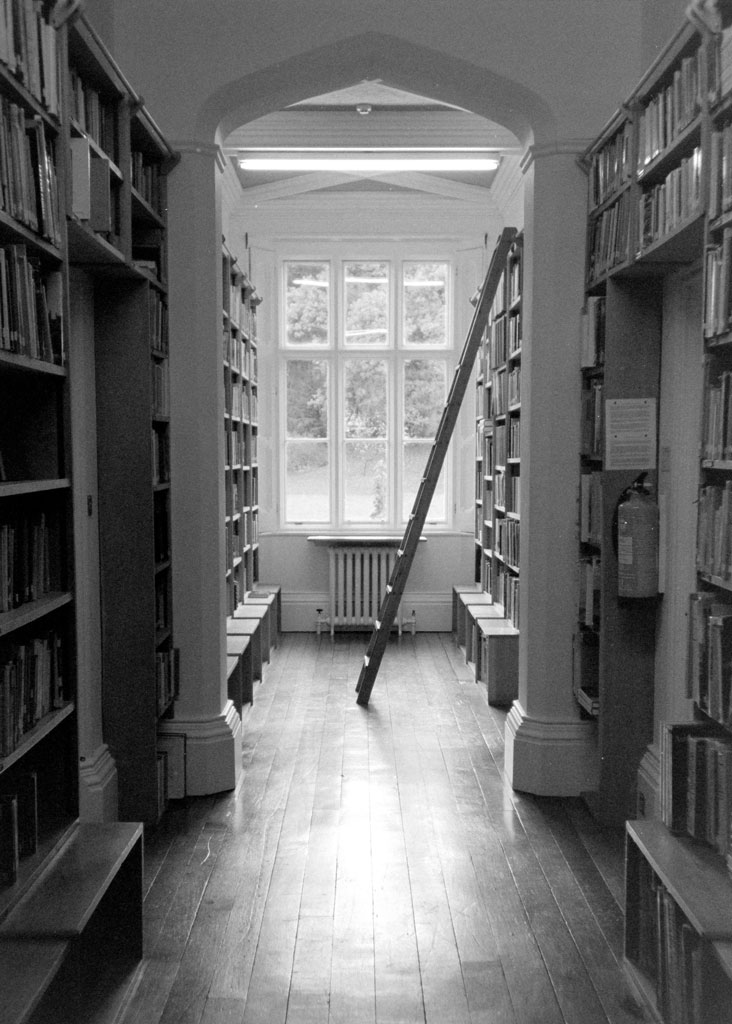

Is that a fair comparison? Can these compacts really perform as well as an SLR? After using both cameras for many years I believe that – as long as you accept the restrictions of a fixed 35mm lens – yes, they can. The Zuiko optics of both the XA and Mju-II can deliver extremely good results if you treat them, and your photography, seriously. The weatherproofing of the Mju-II is especially useful in the UK climate, and I have used one in driving rain without problems – in conditions where I was happy to leave my DSLRs safely indoors.

Olympus XA vs Mju – Verdict

With the advent of digital compacts, many of these classic Olympus ultra-compact cameras were relegated to the dusty shelves of charity shops – which is where I got most of my examples from. In the past, I have seen them on sale for as little as £5, which is a bargain by any measure – even when you factor in the cost of film and a new battery. Recently, however, they seem to have gained a sort of retro-chic and quite nondescript examples have started appearing on Internet sales sites at eye-watering sums, well into three figures.

While I have always found these cameras extremely reliable, I believe you need to think hard about their likely lifespan before committing such serious sums of money. But if you are lucky enough to have one of these classics, then please don’t stick in a drawer or in a display case. Put a film in it, check the battery and stick it in your pocket – because you never know what you might come across.

John Gilbey is a writer and photographer based in West Wales.

Related reading:

- Pentax 17 vs Kodak Ektar H35N – half-frame film cameras compared

- How to check if a film camera works

- 12 Best Second-hand Classic Compact Cameras

- Small wonders: best used compact cameras for winter