There are a few creative exceptions, but one of the fundamental aims of most photographers is to get their subject sharp. Thankfully, that’s the aim of a modern camera’s autofocus (AF) system too but although they are sophisticated, they are not 100% foolproof. There isn’t one go-to setting that guarantees every subject is tack-sharp in every situation. As a result, it’s important to understand how your camera’s AF system works, the conditions that challenge it, and the settings or techniques that will help you to get the results you want.

Using a large AF area makes it easier to track subjects that move erratically. Credit: Angela Nicholson

How does my camera’s AF system work?

There are two types of autofocus systems commonly used today: phase detection and contrast detection. Digital SLRs use phase-detection focusing when the viewfinder is in use, but many (recent Canon DSLRs being a notable exception) actually switch to contrast detection in live-view mode.

Mirrorless cameras operate in full-time live-view mode and use either contrast detection or a hybrid AF system that combines contrast detection with phase detection. Even if they use contrast detection, it’s usually a heck of a lot better than the contrast-detection system used by the average DSLR in live-view mode.

The mechanics of phase detection are a little different depending upon whether it’s used with a DSLR’s re ex mirror or a mirrorless camera’s sensor, but the principle is still the same. The light exiting the lens falls on to two pairs or groups of matched pixels. If the light intensity of the images from these pixels is the same, the subject is in focus. If there is a difference, the subject isn’t in focus and the camera will then calculate which way to adjust the lens.

Contrast detection relies on the fact that a subject has the most contrast when it’s in focus. It’s an accurate method but it can’t tell which way to adjust the lens so it may go one way, then the other. This means it’s inherently slower than phase detection. However, mirrorless camera manufacturers have honed this type of focusing so it’s much faster than it used to be. And developments like Panasonic’s Depth From Defocus (DFD) technology helps cameras like the Panasonic Lumix G9 and GH5 get super-sharp shots of fast-moving subjects.

Auto AF is useful for subjects like this flower which was intermittently buffeted by the wind. Credit: Angela Nicholson

Which AF mode should I use?

There are three main AF modes: single, continuous and auto. Single (S-AF or AF-S) mode is designed for use with motionless subjects. Once selected, the camera attempts to focus when the shutter release or AF-on button is pressed. Once the subject is sharp, it won’t readjust focus until you release the button and press it again.

In continuous autofocus (C-AF or AF-C) mode the camera continues to focus for as long as the shutter release is held down. This makes it the default choice for shooting moving subjects. It also means that it’s the wrong choice if you’re planning to focus-and-recompose. I’d also steer clear of it with stationary subjects as it can ‘fidget’, which slows things down and can mean missing the focus.

Auto autofocus (AF-A or A-AF) mode is a useful choice when you don’t quite know what you’re going to photograph. With street photography, for example, you might shoot a static scene one minute and fast action the next. But if you know what you’re shooting, it’s best to use either S-AF or C-AF because the camera needs to make some decisions in A-AF mode and it sometimes gets things wrong or causes delay.

Eye AF can help you nail the focusing with a wide range of people shots. Credit: Angela Nicholson

What has artificial intelligence (AI) got to do with autofocus?

Face- and eye-detection AF have been around for a little while, and they are useful for social photography. Eye AF is especially helpful because it gets the most important part of the subject razor sharp, leaving you to focus on aspects such as the composition and timing of your shots.

One issue with some face-detection systems is that they incorrectly ‘see’ faces where there aren’t any, which leads to focusing errors. For this reason, it’s a good idea to turn the feature off when you’re not going to use it.

Thanks to increased use of artificial intelligence and greater processing power it seems likely that we’ll see more subjects being detected automatically in the near future. Sony has now extended its Eye AF system to cover animals’ eyes, or at least cats’ and dogs’ eyes, and Olympus’s OM-D E-M1X can detect cars, trains and aeroplanes, while Panasonic’s Lumix S1 and S1R can detect animals. They all work well, making it easier to get those subjects’ sharp.

Even though modern AF systems are incredibly smart, there are occasions when it’s better, or perhaps easier, to focus manually. Cameras usually search the distance for their target, which means that it can be quicker to focus manually on a macro subject, for example. And if you’re shooting through something like water spray from a fountain, or foliage, the AF system is likely to get very distracted, thus making manual focusing a better choice here too.

If you’re using a DSLR, don’t struggle with the tiny viewfinder image while you focus. Instead, activate live view so that you can magnify the focus point and use focus peaking to get the subject completely sharp.

A small AF point gives you precise control over the focus. Credit: Angela Nicholson

Never use auto-AF point mode: true or false?

Most cameras offer a collection of AF-point selection modes that help you to choose the point(s) you want to use. These include options such as single- point, multiple-point, all-point or auto-point, zone and tracking. The smaller the selection area, the more precise you can be with the focusing. However, if your subject is moving, it’s worth selecting multiple-point mode or zone mode as it’s easier to keep at least part of a larger area over it.

In the past I would have avoided using an all-point or auto-AF point mode that puts the camera in full control over which AF point is used (it always just focused on the nearest or most central object), but Sony’s recent AF systems have changed that. Its Wide and Zone Focus Area modes work brilliantly and in continuous autofocus (AF-C) mode in models like the A6400 and Alpha 7 III, they’re great for tracking a moving subject. But it’s worth noting that they usually target the nearest part of the subject and if it stops moving, it’s prone to focusing just in front of it.

Sony’s Lock-on AF and Real-Time Tracking modes work in a similar way to other manufacturers’ tracking modes, but are better than most. You start by placing the point over the subject, and then press the shutter release to activate the focusing. Once you start shooting, the camera is in control over where the AF point goes. It usually follows the subject, but if it strays you have to stop shooting to reposition it.

Most tracking AF modes aren’t as fast or accurate as Sony’s, but can be useful with slower or motionless subjects. For example, you can place the starting AF point over a critical part of a subject and it should stay with it as you recompose.

When shooting a portrait wide open with an 85mm lens it’s best to select an AF point rather than focus and recompose. Credit: Michael Topham

I like to focus and recompose – is this OK?

When cameras had one AF point we often had to focus and recompose the shot before taking the image. However, simple trigonometry tells us that this can lead to focusing errors. If you’re shooting a portrait with an 85mm f/1.4 lens wide open, for example, the depth of field is so shallow that using the central point to focus on the eye and then recomposing can result in the eyebrow or nose being sharper than the pupil. Consequently, it’s much better to compose the shot and use the AF point that’s closest to the object you want to be sharpest.

Why use the back button?

Even with high frame rates, it’s important to time your shots carefully. Back-button focusing can help with this by taking away the shutter release’s AF activation duty. Instead, you use the AF-on button on the back of the camera (or via a customised button) to control the AF system, and only press the shutter release when you want to take a shot.

This is especially useful when you’re capturing action. With motorsports, for example, you might want a car to appear at the apex of a bend. To help with this, you can set the focus with the AF-on button and it won’t shift when you press the shutter release to take the shot.

Most cameras struggle to focus on a silhouette unless you put the active AF point over the edge where there’s some contrast. Credit: Angela Nicholson

My AF system is struggling to lock on – what should I do?

Focusing systems need light and contrast to work. It’s the lack of contrast that can leave a camera struggling to focus on a well-lit sheet of paper or a smooth wall. If you can find some point of contrast, even if it’s just a join in the wallpaper, it will often snap into focus quickly.

Because the phase-detection sensors in a DSLR are often arranged in lines, the detail needs to cross a line rather than run along it for it to be ‘visible’ to the AF system. Consequently, it’s a good idea to understand your camera’s AF sensor arrangement. It’s also why cross- type AF points are useful – they can detect details in more than one direction.

If your camera is struggling to focus, look for an area of contrast or consider switching to the central AF point. As well as being cross-type, this is usually the most sensitive in a DSLR.

Cameras sometimes have multiple cross- type AF points and it’s worth knowing where these are, especially when shooting action in low light.

Knowing how your subject moves can help you decide on the ideal AF customisation settings. Credit: Angela Nicholson

Is it worth customising my AF system?

Some cameras have a series of customisation settings for the AF system. These affect aspects such as how the AF responds to a change in the subject distance or if the subject moves from the selected AF point.

Many photographers assume that it’s best to set the camera to react quickly to any change, but a little pause can be a good thing. For example, if you’re photographing a swimmer doing the breaststroke towards you, with a fast setting the camera will refocus on the far end of the pool every time they bob underwater. Then when they reappear it will refocus again, making a major adjustment. A slower reaction will help the camera stay on the subject.

To get the best from these customisation systems you need to consider what you’re photographing as well as the shooting conditions – for example, whether any objects are likely to come between you and the subject.

AF mysteries explained

- What is the focus limiter switch for? If your subject is going to be within a specific range it can be helpful to use the lens focus limiter to prevent it from hunting across the entire focus range.

- What is focus stacking? This technique involves shooting a series of images, each with a slightly different focus distance. The images are then composited into one that has much greater depth of field than an individual shot. It’s a very popular technique with macro photographers.

- Why does AF depend on the lens I am using? Different lenses have different motors that drive the focusing and different weight elements. Also, lenses with a wider maximum aperture let in more light, which helps the AF system.

- Why are full-frame DSLRs’ AF points near the centre? Vignetting as well as the main and secondary mirror arrangement of a DSLR mean that the AF sensor is smaller than the imaging sensor. As a result, the AF points are central.

- Can f/5.6-sensitive AF points be used at smaller apertures? Yes. The focusing takes place with the aperture wide open, so as long as you use a lens with a maximum aperture of f/5.6 or greater, it will work.

Does a new lens need to be calibrated?

Manufacturing tolerances can result in a DSLR’s AF sensor and a lens not being perfectly matched, which means that your subject isn’t as sharp as you might expect. Thankfully, high-end cameras have a lens calibration or AF Microadjustment feature that allows you to correct this problem. The following steps show how the AF Microadjustment feature works using a Canon EOS 5D Mark IV and a calibration target created from a free template downloaded from the internet at www.squit.co.uk/photo/files/FocusChart.pdf.

1. Set up your target

Assemble your calibration target and mount your camera on a tripod at least 25x the focal length of the lens away. Next, select mirror lock-up mode.

2. Use the widest aperture

Set the widest aperture and put the centre AF point over the chart focus marker before focusing and taking a shot. Refocus again and repeat until you have five images.

3. Review the images

Open the images on your computer and examine them at 100% on screen to see whether the camera is focusing the lens in front of or behind the intended target.

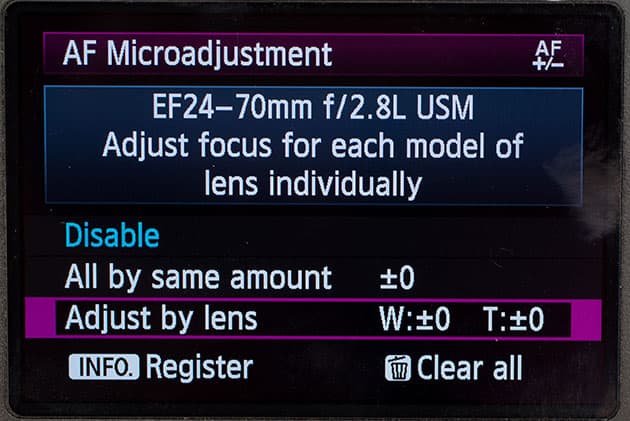

4. Find AF Microadjustment

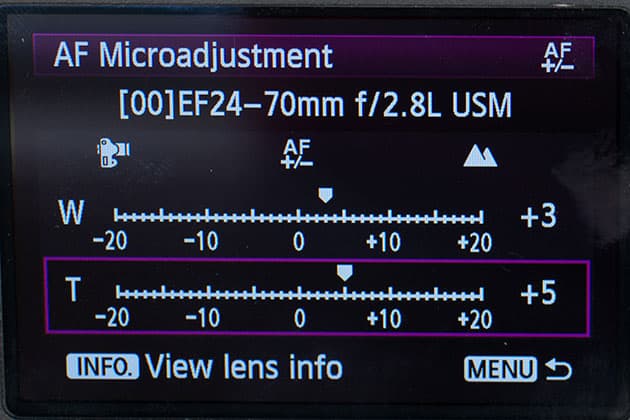

From the menu, select AF Microadjustment in the AF options. Press Set and scroll down to ‘Adjust by lens’ before pressing the Info button to access the options.

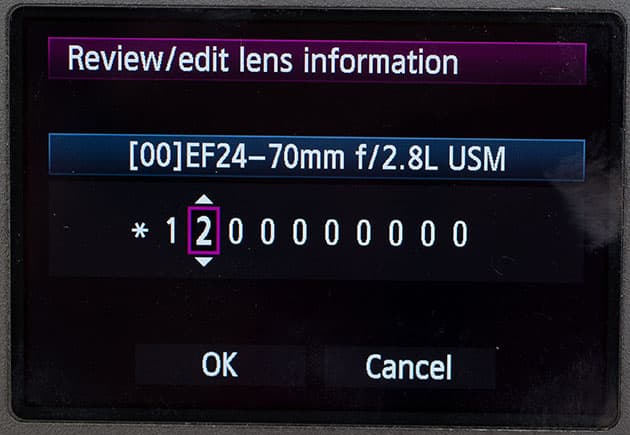

5. Check lens serial number

Press the Info button again to check the lens serial number. If necessary, use the Set button and main dial to enter the correct number, then select ‘OK’.

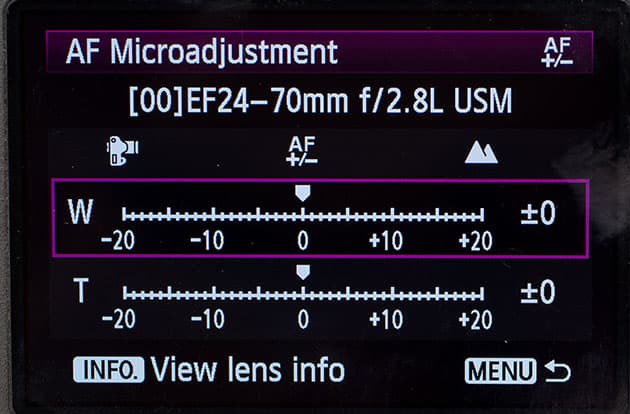

6. Adjust focus point

You can adjust the focus point of the shortest and longest focal lengths. Use the scroll dial to select the focal length that you want to adjust, and then press Set.

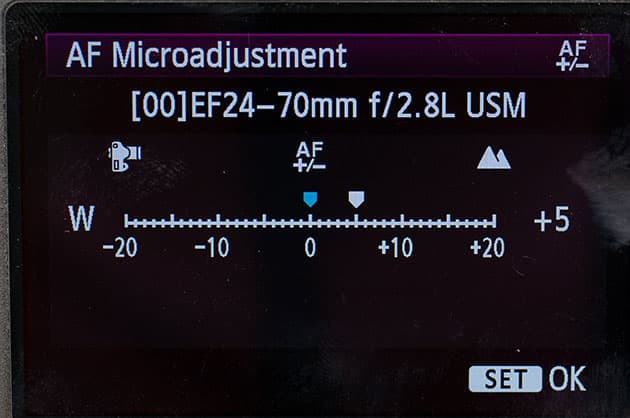

7. Set focus adjustment

Use the main dial to set the focus adjustment; use a positive number to correct front focusing and a negative one for back focusing. Press Set followed by the Menu button.

8. Refine the calibration

Shoot the target again and examine the images to assess the impact of the adjustment. If necessary (it probably will be) repeat the adjustment process to refine the calibration.

9. Repeat for other lenses

If you’re calibrating a zoom lens, repeat the adjustment process for the longest focal length once you’ve got the focusing right for the shortest focal length.