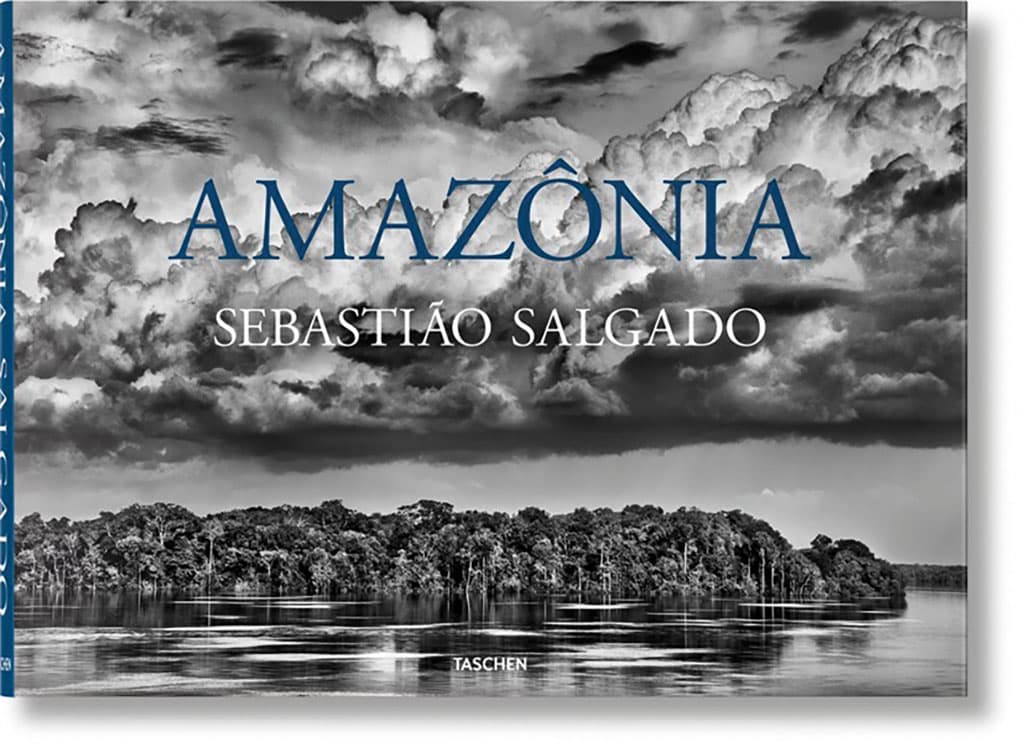

Sebastião Salgado’s new book, Amazônia, takes us on an extraordinary journey through his time in the depths of the South American rainforest. Damien Demolder finds out more..

There have been a few instances during my short lifetime that have had a dramatic impact on my photography. The principal one, of course, was getting my first camera but another key moment came while lying on the green carpet of my parents’ lounge when I was a teenager. It was here, propped up with a cushion under my elbows, that I consumed the Sunday papers, and here that I first saw pictures by Sebastião Salgado.

The Sunday Times colour supplement had a significant section devoted to an astonishing project that depicted what looked like scenes from Dante’s Inferno, as muddied bodies carrying great sacks of dirt climbed rickety long ladders made of branches as they made their way up the wet muddy walls of a mine.

The hole they emerged from must have reached to the centre of the Earth, and these bustling sinners took their eternal punishment packed together in astonishing numbers as they lumbered under the weight of past deeds. These were, of course, the legendary pictures Salgado took in 1986 of the gold miners hunting for their fortune in the gigantic pit at Serra Pelada in the north Brazilian state of Pará.

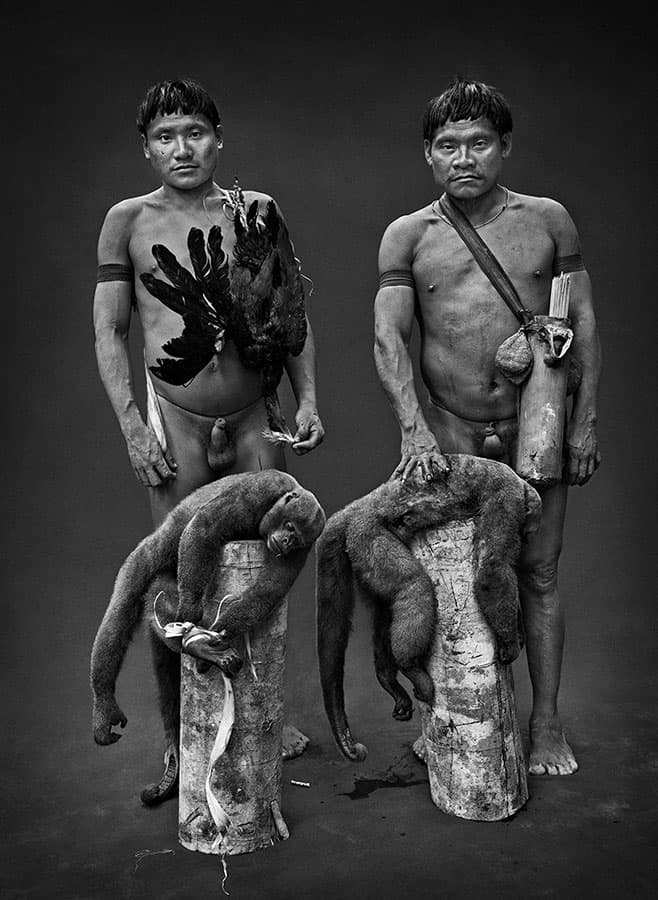

Hunting encampment, Valley of Javari Indigenous Territory, state of Amazonas, 2017

At the time I was wavering between becoming a musician and a photographer, and Salgado helped me to make up my mind – luckily, as I was much worse than I thought at the trumpet.

Salgado’s latest book, Amazônia, shows us the world in the same deep black & white tones that he showed us the gold miners – a style which is almost a trademark of his work. This time though we look not at Hell on Earth but what appears to be a piece of Heaven.

In this beautifully printed, weighty volume Salgado takes us on a 20-year tour of the Amazon region to meet not only its rivers and trees, but the tribes that live in its depths – some of which have had very limited exposure to the world beyond the forest. It’s an exploration, an adventure and an incredible education.

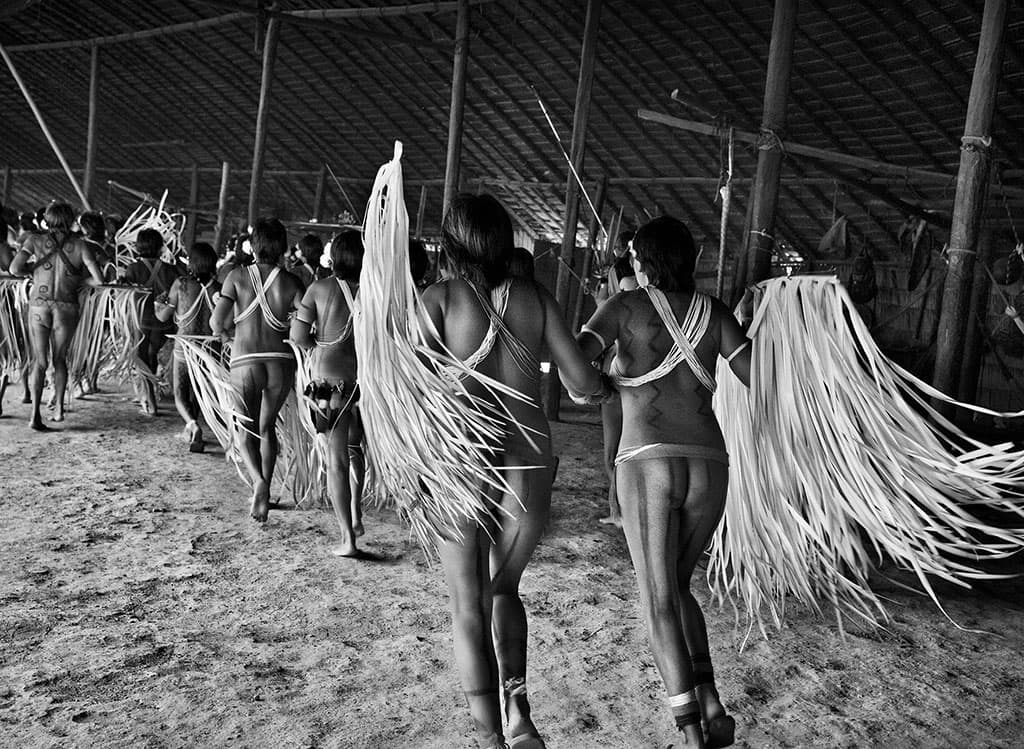

Women dance at the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, state of Amazonas, 2019

Life from all angles

Salgado shows us this world in a number of different ways. He avoids the standard ‘native with distant stare’ in favour of informative documentary images of tribal people going about their business, slightly more posed pictures of them in their environment as well as formal portraits against a series of canvas backgrounds; that his team incredibly hauled along with them on their trips. We get to see village life, fishing and hunting, people at leisure as well as engaged in the significant events of their culture.

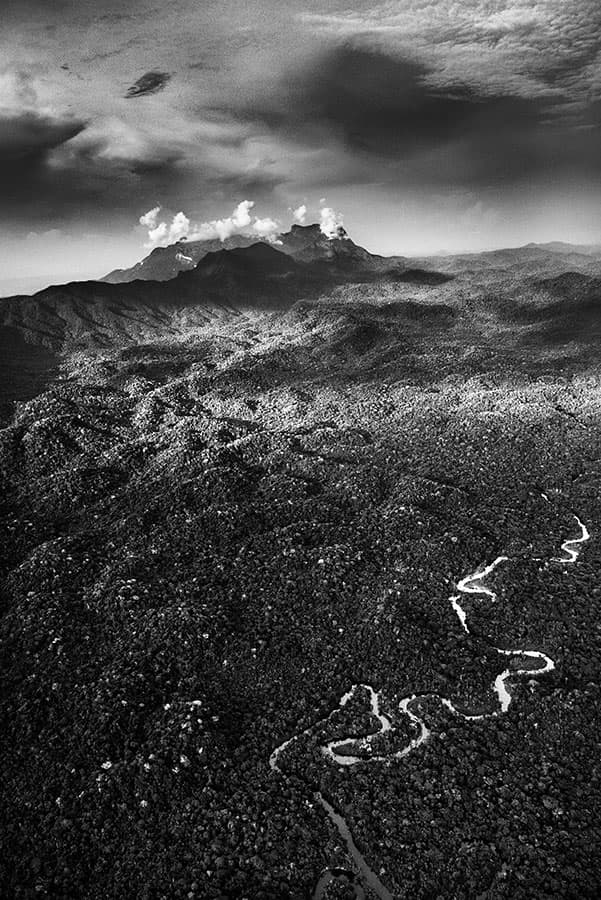

As Salgado travelled to many of these tribes by air we also get aerial views of the stunning Amazonian landscapes; forest broken by ‘serpentine’ rivers, mountains bursting out of the canopy and clouds – lots of ‘rivers of the sky’ and stormy looking formations. It is a quite astonishing collection of images that shows us what we might once have thought of as a world left behind, but which seems now a world very much more balanced and at peace with itself than our own.

The Maiá River in Pico de Neblina National Park. Yanomami Indigenous Territory, state of Amazonas, 2018

My first thought on receiving the book was that perhaps the best way to ensure the survival of the ten indigenous tribes featured would be not to feature them in a book that a whole world of photographers would then want to emulate. Salgado goes to some length though to explain how the tribes are protected from the outside world as well as the threats that still need to be dealt with. Highlighting them in such a high-profile way, it is hoped, will ensure that those who have the power to protect this land and these people will do so.

Salgado tells us too at the beginning of his substantial text that ‘one aim of this photographic project is to record what survives before any more of it disappears’, and he ends with ‘My wish, with all my heart, with all my energy, with all the passion I possess, is that in 50 years’ time this book will not resemble a record of a lost world.’

The unseen

Photographers strive for originality, and for many this means showing their audience things that haven’t been seen before. There aren’t many things we can photograph these days that haven’t been photographed over and over, so a good deal of the attraction of this book is what it shows us for the first time. There is an undeniable wow-factor in that. Of course we have seen tribal people before, and some may have photographed some themselves at tourist hot-spots, but the vast majority of the people and the villages shown here have rarely been seen before, and their way of life isn’t for show.

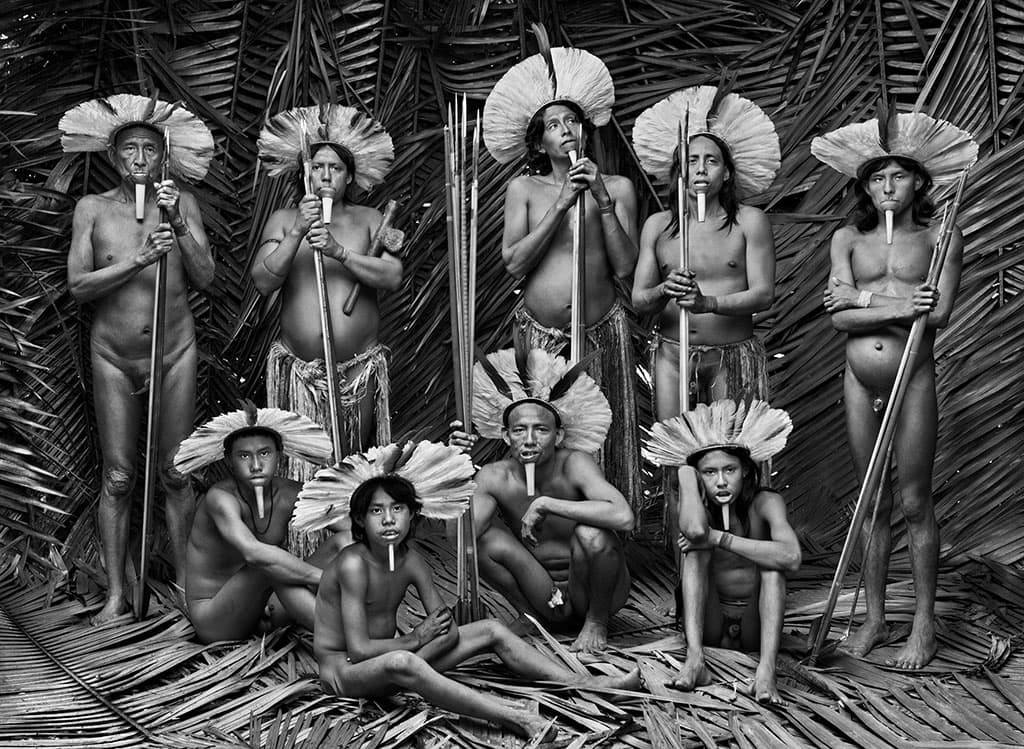

Men of Zo’é ethnicity, Zo’é Indigenous Territory, state of Para, 2009

The photographer has clearly spent the time to get to know the people in the pictures too, and to understand what they are doing. The captions provided name the sitters, their positions in the village and add some other interesting information to help the reader appreciate what is going on. I suspect it is for artistic reasons that the captions are grouped together at the end of the book so the pictures can stand on their own, but it’s also a bit inconvenient as the book is large and flipping backwards and forwards is awkward.

Had Salgado provided less-interesting captions then this might not have been an issue, but he goes to a good deal of effort to make the captions really worth reading. Each of the tribes is also introduced with historical, geographic and cultural information, and we get to read about their customs, what they eat, their beliefs and how they spend their time. And it’s fascinating. Not wanting to drop in any spoilers, but the women of the Zo’é tribe have multiple husbands, ‘one a hunter, another a fisherman, a third a farmer, and a fourth who helps at home’ – and other interesting facts and stories.

Salgado worked very closely with FUNAI – the National Indian Foundation – for this project, with the foundation helping to provide guides as well as guidance and guidelines for his trips. Together they determined which tribes to visit, gained permissions from the tribes themselves and found out what the tribes needed that Salgado could take as a gift.

An igapó, a type of forest frequently flooded by river water. Anavilhanas archipelago, Anavilhanas National Park, state of Amazonas, 2019

Salgado’s team had to remain self-sufficient for food as they weren’t allowed to accept meals from the tribes, and had to spend time in quarantine and having medical tests to ensure they wouldn’t carry diseases to people who have no defence against them. Salgado says in the book that, ‘History has shown that isolated indigenous peoples face no greater danger than contagious bacteria or viruses introduced by outsiders.’ An enormous amount of preparation was needed as the teams would often be on the go for weeks at a time.

The pictures

As you would expect, Salgado’s pictures are more than well worth looking at, and his experience as a story-teller comes through very clearly. The pictures are visually stimulating in their own right, and need no dramatic post-processing to make them so. The photographic process never distracts us from the subject matter or the situations shown, and no techniques to create ‘impact’ are used. The pictures are ‘straight’ and just plain very-well-taken. Salgado gives us depth, composition that shows us the subject and its environment, and steers clear of extreme photographic exhibitionism.

Foliage glows in many of the environmental pictures creating a magical look, and skin tones are deep and rich, while the portraits against the canvas backgrounds allow us to see the people away from their environments, and in some cases help us understand family and social groups. Had these out-of-context portraits been shown on their own they might have looked like a dressing-up session, but alongside the other work in the book they add a really interesting dimension to the whole picture.

A young Marubo girl, Ino Tamashavo, holding a parakeet. Valley of Javari Marubo Indigenous Territory, state of Amazonas, 1998

Salgado is known of course for his definite black & white style, which perfectly suits so many of his projects, but I couldn’t help wishing that this book had been in colour. The photographer says that colour can be a distraction and can disguise the message of the work, which in general terms I agree with. It can however also make us feel closer to the subject.

Colour would make me feel more of a connection with the people in the book, and make me feel less like I am looking at a historical and scientific record of some abstract situation that could have happened at any moment in history. I want to understand that these people are living now, as I write this, in the deepest forests of the Amazon. Somehow the monochrome takes some of that element away.

I want to know what shade of green the forest is, but Salgado shows us pages of aerial views of the lush landscape with this information removed, redacted, censored. The skies and cloud formations are dramatic of course, with what looks like a red filter or red channel conversion, but in black & white they miss out on the wonder that Yann Arthus-Bertrand so famously captured in his Earth From Above series. Is it to be more ‘serious’? I don’t know, but it’s a bit of a shame all the same.

Amazônia by Sebastião Salgado is available to buy now, published by Taschen. RRP £100. ISBN: 9783836585101

Conclusion

In colour or black & white the Amazon is a fascinating place, and Sebastião Salgado has created a truly sensational body of work that he shows us in Amazônia. The pictures are stunning, the printing first rate and the generous accompanying text is full of interesting, and carefully recorded, information. That Salgado takes as much care to record the details of each tribe and person he photographs as he does over the way he photographs them, really adds an extra depth to this book that we don’t always get.

His own emotional investment in the place and the subject comes streaming through, which is one of the things that make this a very special book. It is a big, thick tome, and while £100 is a lot to pay for a photobook you do actually get a lot for your money.

Further reading

Get the most out of your travel photography

Book review: Exodus by Sebastião Salgado

Photographer Sebastião Salgado to win prestigious Royal Geographical Society award