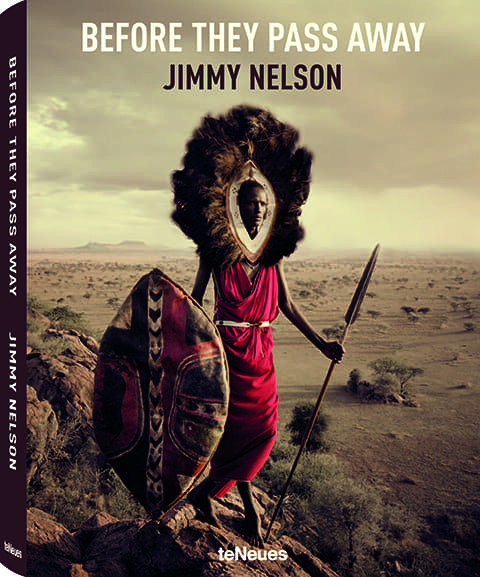

Picture: Nelson’s book, Before They Pass Away

In 2010, UK-born photographer Jimmy Nelson set out to find the world’s ‘last indigenous cultures’, to document them for future generations in his book Before They Pass Away, first published as a coffee-table version last October.

Nelson says the project was designed to be a ‘controversial catalyst for further discussion as to the authenticity of these fragile, disappearing, cultures’.

However, earlier this week he came under attack from Stephen Corry, director of Survival International, who wrote a review of the book on the Truthout website.

Corry accuses Nelson of ‘hubristic baloney’ and of documenting people ‘as they looked a generation or two earlier’. Some images are a ‘photographer’s fantasy’, he claims.

‘The subjects are posed as if they were models in the advertising salons where Nelson developed his career,’ wrote Corry in his review.

Responding to the accusations, Nelson, who used a 4x5in camera on his travels, told Amateur Photographer that his subjects were ‘directed, staged to portray the various individuals’.

But, he adds, ‘it was done in co-operation and consent, and entails much more of their own way to present themselves than my small adjustments, and maybe improvements, in the most celebrated light technically possible’.

Picture credit: Jimmy Nelson

Corry questions how much Nelson’s images portray reality. ‘In his photos of the Waorani Indians of Ecuador, he has them unclothed, except for their traditional waist string.

‘The Indians are not only shorn of their everyday clothes, but also of other manufactured ornaments such as watches and hair clips.

‘In real life, contacted Waorani have routinely worn clothes for at least a generation, unless, that is, they are “dressing up” for tourists…’

Nelson retorts that his photos are as real as any since the invention of the medium in 1839, arguing that every image is a ‘subjective, creative document of the photographer’.

‘They are all real pictures of real people. All the images represent who they really are. Although the difference is that I chose to also celebrate the participating persons and put them and their stories in a positive light, their beauty on a pedestal.’

Nelson concedes that cultural representation is a ‘slippery platform’ and suggests he shot his subjects in a way that would attract wider attention.

He says: ‘But it is not too slippery to dare and discuss and, yes, use the exotic, distant and different, which makes it more immediate and attractive to a wider and perhaps, originally, not so interested, new audience.’

Picture credit: Jimmy Nelson

Nelson says he has produced ‘a very personal document, which has grown a commercial skin’.

He adds: ‘It goes without saying that producing an important project of this scale requires enormous investment, hence the occasionally pompous way in which it presents itself…’

Nelson (pictured below) points out that he spent eight years as a photojournalist and grew up in countries ‘not yet developed’ in the Western sense.

‘These combined hands-on experiences enabled me to develop an objective aesthetic of our rapidly globalising world.’

Nelson says that everyone he photographs is asked to pose in the same way we pose ourselves, ‘that is if we feel… worthy and have something to say and show’.

All picture credits: Jimmy Nelson