Legendary documentary photographer Sebastião Salgado took amazing photos whatever camera he used. Former AP editor Damien Demolder pays tribute to this hugely influential artist, who drew attention to the injustice and suffering of the world’s poor through his astonishing style.

On Friday May 23rd, the renowned documentary photographer Sebastião Salgado died at the age of 81 from leukaemia and complications from a bout of malaria he contracted in Indonesia in 2010.

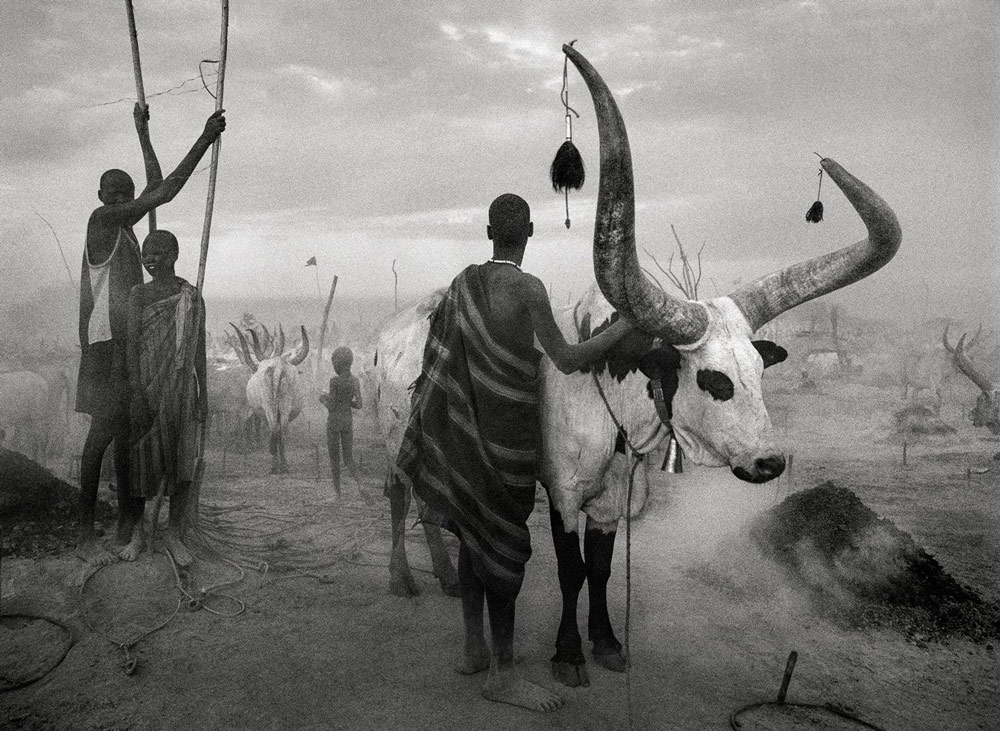

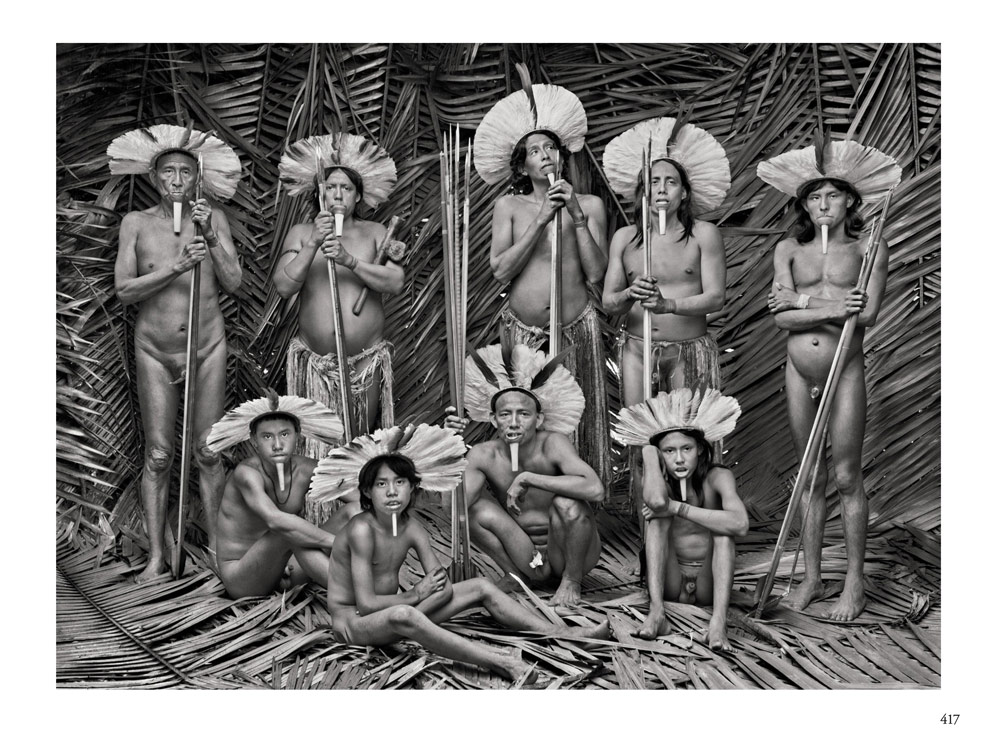

Well known for his large scale and long term projects highlighting the plight of threatened cultures, environments and people, Salgado approached his subjects with a deep humanity that was reflected in images that conveyed a powerful connection with the viewer.

Always working in black and white, firstly with film and then with a digital camera, Salgado and his wife Lélia Wanick Salgado created books, prints and touring exhibitions of his work to ensure the message could be imparted to as wide an audience as possible.

Salgado’s dedication to a story, his compassion and the years he spent exploring one subject afforded his work such extraordinary depth that he was able to show the previously unseen and unnoticed, and the dramatic style he used to make his images captured the attention of the world’s picture editors and the eye of their readers. He is survived by his wife and their two sons Juliano and Rodrigo.

A dramatic backstory

Sebastião Ribeiro Salgado was born on 8th February 1944 to cattle rancher parents in a small town called Aimores in the Minas Gerais state of the eastern part of Brazil. There was no secondary education where he was brought up, so he moved 185km away to Vitoria for school, and then in 1962 he moved again to study for a degree in Economics in the state of Espirito Santo, then once again for a Masters in economics in Sao Paulo.

His doctorate in the subject was earned at the University of Paris (1969), before he moved to London in 1971. At this stage he’d already met and married Lélia in 1967, and they initially moved to Paris to escape the human rights abuses, censorship and murders of the military dictatorship that ruled Brazil after the coup of 1961.

Striking gold

In London Salgado worked as an economist for the International Coffee Organisation – a job that required him to travel to Africa for assignments in partnership with the World Bank. During these trips he began to take pictures of the workers and places he encountered, and realised quite quickly that he preferred being a photographer to being an economist.

Consequently, after two years, he left his job and London, and returned to Paris to join the Sygma photographic agency. Covering stories for Sygma, Salgado travelled to Portugal, Angola and Mozambique, recording the African nations’ wars of independence from Portugal and the internal conflicts that came about in the aftermath.

He moved to the Gamma Agency in 1975 and covered other similar situations in Africa, as well as stories in Europe and Latin America. It was during this period he began his long essay on native Indians and peasants in Latin America that eventually became the book Other Americas in 1984. Recognised for the quality of his work, Salgado was invited to join the Magnum agency in 1979.

Here he continued to shoot news stories from around the world, and recorded the attempted assassination of President Ronald Regan in Washington in 1981 for the New York Times magazine. It was during his time at Magnum that Salgado shot his famous story about the gold miners of Serra Pelada that made him a household name.

Working with Granta

Salgado had been sent to South America to shoot an assignment for German Geo magazine, and had then stayed on to shoot his own project to kick off his Workers series. The gold mine at Serra Pelada had been shot many times before, but usually in colour and over the course of a day or two. Salgado stayed for four weeks to really immerse himself and, of course, shot it in his trademark black and white.

Salgado’s UK agent, Neil Burgess, at that time was working for Magnum taking photo stories to the newspaper offices around London hoping to get them published or to pick up new commissions. Salgado was one of the photographers at the agency and had told Burgess about his project in Serra Pelada, and that he hoped a magazine called Granta would take the pictures.

‘Granta was and is, a respected literary magazine that sometimes publishes a photo-essay’ says Burgess, ‘but they never paid very well and the reproduction back then was awful. We didn’t speak again until March 1987 when he had edited and printed the story and again he asked me to take the pictures to Granta. He was enthusiastic about the story, but when I suggested maybe one of the bigger magazines might buy it, he thought it was unlikely, because, as he said, the story had been photographed many times before.’

Pictures from Paris

‘The package from Paris, with the pictures, arrived on my desk one morning and I pulled from the envelope a box with about forty 24 x 30cm beautifully made black and white prints. I knew immediately I looked through the set that I wouldn’t be taking the work to Granta. This was a virtuoso piece of photography – Salgado had used a complex palette of techniques and approaches: landscape, portraiture, still life, decisive moments and general views.

He had captured images in the midst of violence and danger, and others at sensitive moments of quiet and reflection. It was a romantic, narrative work which engaged with its immediacy, but had not a drop of sentimentality. It was an astonishing piece of work, an epic poem in photographic form. It was my first year running Magnum and I remember thinking, ‘imagine if I get even one story a year as good as this!’ Forty years later I realise how lucky I was to ever receive any story as good as this.

‘An hour later I walked into the office of Michael Rand, the Art Director of The Sunday Times Magazine (who also sadly died recently aged ninety six). This was the man who virtually invented the newspaper colour supplement magazine in the UK. I don’t believe I actually said anything. We just went through the pictures together. About halfway through the set, a look from Michael prompted his picture editor Suzanne Hodgart, she asked me how much we wanted? I doubled the highest price I’d ever received for a photo-story, to which Michael, without looking up, responded immediately with,

“Yes, sure.” I realised later that if I’d asked ten times the amount, then we might have had to haggle a little, but they would have still bought it.

‘The story was published over six pages in The Sunday Times Magazine at the beginning of May 1987. Michael Rand’s lay-out was very clean with the minimum of text; he regretted later that he hadn’t given it another two pages, but it looked fantastic.

Going into my office the next morning, the phone didn’t stop ringing; editors from other magazines calling me, demanding to know why I hadn’t offered them the story first? Mark Hayworth-Booth, the curator of photography at the Victoria and Albert Museum rang to ask to buy prints from the set for their collection. Paul Arden, then, the Chief Creative Director of Saatchi and Saatchi, the biggest advertising company in the world, rang; could he buy some prints and would Salgado work for him? Sure, I said, if we found the right project.

‘The Serra Pelada story had excited people across the full spectrum of visual professionals in art, commerce and journalism. It affected the public too, Philip Clark the editor of The Sunday Times Magazine, told me some weeks later that he had never, in a very long career, had so many letters from members of the public about a single story; hundreds of them.

‘Some people spent just a few hours, photographing the spectacle of 50,000 men digging for gold in the mud in the middle of the Amazon. Salgado, on the other hand, had shot exclusively in black and white and spent around four weeks living and working alongside the mass of humanity that had flooded in, hoping to strike it rich.

‘The story was the epitome of Salgado’s Workers thesis: that manual employment, the very thing that defined the proletariat, the ability to sell ones’ labour, was coming to an end, and about to be superseded by mechanisation and computerisation. Very soon after his visit, the 50,000 men digging with picks and spades were replaced by modern mechanical mining techniques.’

Workers of the world united

This project in Serra Pelada was the starting point for the book that became Workers, which was published in 1993. The book’s subtitle is An Archaeology of the Industrial Age, and included images of manual labourers from all over the world captured in 350 photographs. Workers had been preceded in 1988 by another epic book, Terra: Struggle of the Landless, which told the story of the forced migration of Brazilian peasants and their decent into even greater poverty.

The project didn’t just remain represented in book form though, as it became a touring exhibition that was shown in over 100 Brazilian cities as well as in 40 countries internationally to ensure as many people would see the work as possible.

Another of Salgado’s seminal works is Exodus: Humanity in Transition, also known as Migrations. Published as a book in 2000, the project had taken six years to shoot and had lead Salgado to document the mass movement of people around the globe from 40 countries. He focused on displacements caused by war, famine, poverty and environmental issues, including Latin Americans moving to the USA, Jews leaving the former Soviet Union, refugees from the Bosnian conflict and Africans migrating to Europe, among others.

The year 2004 saw the publication of a project Salgado had started in 1984 in the drought-stricken Sahel region of Africa. Sahel: L’Homme en Detresse, or Sahel: The End of the Road, covered malnutrition and famine across Chad, Ethiopia, Mali and Sudan during a period in which a million people died. He worked alongside the charity Médecins Sans Frontières, with the project supporting the charity’s work. The project took 18 months to shoot – a relatively short time for Salgado – and resulted in the 160-page book.

A change of direction

War and death began to take its toll on Salgado however, and eventually he felt the need to point his lens in new directions. He had left Magnum in 1994 to establish his own picture agency, Amazonas Images, in the same year he covered the genocide of 800,000 Tutsis by Hutu extremists during a period of just 100 days in Rwanda. The experience had a profound impact on him, and nearly ended his photographic career.

In the introduction to his next book, Genesis, Salgado explains how he lost and then regained faith in humanity and the world. ‘At the end of the 1990’s, I completed a long series of photo essays on the unparalleled movement of peoples across the globe’ he wrote. ‘It involved recording the massive migration of peasants from rural areas to cities on several continents. It led me to follow destitute refugees fleeing armed conflicts and natural disasters and I accompanied young men willing to risk all in the hope of finding a better life in some far-off land. I witnessed much suffering and great courage, but most of all I saw violence and brutality such as I had never even imagined before. By the time the project was over, I had lost all faith in the future of humanity.’

His introduction goes on to explain that at about that time his father asked him to take over the family farm in the Vale do Rio Doce, where he had grown up with his seven sisters. In his childhood the place was ‘surrounded by tropical vegetation alive with birds and wild animals, by rivers full of fish and by rolling hills that set us imaging the world beyond.’ But by the time Salgado went back to the farm ‘this paradise had vanished. By the mid-1990’s, as with so many farms in the region, deforestation and erosion had left the land lifeless.’

New shoots

Salgado’s wife Lélia suggested they attempt to replant the forest, which they did with over 300 different species – in the end planting over three million trees. As the trees and plants grew and turned the land green again, animals and flowers returned, and instead of flash floods in heavy rain rivers formed that attracted fish back to the area. Inspired by what he saw Salgado initially decided his next photographic project would highlight the dangers of humanity’s abuse of the planet, but then changed his mind to instead show the parts of the world still untouched by the devastations of the rest of the world.

Eight years later, and after ‘32 trips to distant corners of the globe’ the Genesis project became a book that was published in 2013. It’s a gigantic book too, with over 500 pages packed with large-scale and striking images.

It was during this project that Salgado switched from film to digital cameras, a change that required some technical adjustments to ensure the images maintained the same look and feel from the start to the end of the project. The answer was to add software grain that matched his usual film stock to the digital files, and to then make film inter-negatives from these files so that they could be printed in the same way, and onto the same paper, as the film images. The project began in 2004 with a trip to the Galapagos Islands, and ended in 2012 comprising a mixture of landscapes, portraits, social documentary and some stunning wildlife from some of the remotest places on the planet.

Salgado’s final project was Amazonia, which became a book only quite recently – May 2021. Again, an adventure of epic proportions sits within the pages, and a series of trips spanning six years. This time though the subject could be covered in one country, and it’s perhaps fitting that Salgado’s final act was played out in the country he was born in. Amazonia is the story of the vast Amazon forest, its rivers, its trees, its wildlife and the people who make their home there. With great planning, and extensive precautions to protect those unused to modern disease, he visited remote, little-known communities and recorded their daily lives, their relationships and their environments.

The subject matter perhaps reflects Salgado’s hopes for the forest he and his wife had recreated on their own land, and the book provides an optimistic ending to a life recording death and despair. Salgado himself said ‘My wish, with all my heart, with all my energy, with all the passion I possess, is that in 50 years’ time this book will not resemble a record of a lost world.’

A man who touched many lives

I asked Neil Burgess, after all the travel, stunning exhibitions and incredible books, what Salgado’s legacy would be. ‘He thought, or hoped at least’ Neil said, ‘that he would be remembered for the work he and Lélia have done creating The Instituto Terre, the reforestation project they started in 1993.’

Salgado may well have seen his new forest as his greatest achievement, but photographers all around the globe will remember him for the motivation he lent them, as well as the inspiration for many actual and fantasy projects. Indeed, I’m writing this piece for Amateur Photographer because at the age of 17 I saw those Serra Pelada goldmine pictures in The Sunday Times colour supplement and realised what I wanted to do with my life.

Don’t miss this discussion of Salgado’s legacy

If you are as moved by Salgado’s work as we are, don’t miss the panel discussion paying tribute to him at our forthcoming Festival of Photography: Documentary at the Royal Geographical Society in London on August 9th. Panel members include:

- Veteran photojournalist and Magnum Photos member, Ian Berry

- World Press Photo award winner & British Press Awards Photographer of the Year, Edmond Terakopian

- Neil Burgess, formerly Salgado’s UK agent

- Nigel Atherton, group editor of Amateur Photographer. You can watch Nigel’s 2023 interview with Salgado here.

Full details and tickets available from here.