Jeremy Walker’s love affair with photographing ruins and their histories has run parallel to his career as one of the UK’s most revered landscape photographers. He first mooted the idea of publishing his ‘ruins’ series over ten years ago, and has repeated his intentions at regular intervals ever since, so to see this body of work so lovingly compiled in his new book, Landscape, a panoramic coffee table book into which he’s poured so much heart and soul, is very rewarding. Read on for Jeremy’s insights into how to get better photographs of ruins…

St Mary’s Church, Tintern, Monmouthshire Nikon D810, 19mm PC-E, 1.3 seconds at f/11, ISO 64

‘Hanging around in hail storms, researching in the rain, and generally just waiting, no matter what the conditions, is all part of being a landscape photographer,’ he says. ‘The occasions when you just turn up, witness a great sunrise and then go home are few and far between. Waiting is the key to so many images and, as a professional, more often than not I have the time to hang around; I’m not rushing off to do a real job.’

The project slowly evolved from an epiphany experienced along the wild Northumberland coast. He’d been composing a shot of Dunstanburgh Castle and had instinctively framed up with the iconic ruins playing second fiddle to the remote headland and North Sea. ‘I started to question whether it was a landscape, a picture of the castle, or a seascape,’ he explains. ‘The image didn’t work very well without the castle and I started to think about how it played a role within the landscape, not only compositionally but historically and strategically as well. I then found myself shooting landscapes with a ruin somewhere in the image, trying to convey why a particular structure is located where it is.

Fussells Iron Works, Mells, Somerset. Three images stitched Nikon D810, Zeiss 35mm, 8 seconds at f/11, ISO 100

The historical aspect was important from the start. Although I wasn’t aware of many of the historical details when I started shooting and have barely scratched the surface, the brief historical notes in the book give the whole project context. I don’t think the history influenced the photographic process, but the type of structure and its setting would certainly influence my approach and the type of image I was after. Castles with dubious histories and quarries with unscrupulous owners don’t deserve golden skies and pretty sunrises and so a great deal of time was spent hanging around on grey, gloomy days.’

Darker mood

Anyone familiar with Jeremy’s ‘normal’ work will recognise a slightly darker mood throughout Landscape, a subtle shift that he attributes to the subject matter and its often turbulent past. ‘I’ve probably gone a bit meaner, moodier and more atmospheric,’ he agrees. ‘I deliberately chose to shoot when perhaps many photographers wouldn’t even get their cameras out of the bag. Plus, one or two of the locations I had no choice but to shoot. They were a long way from home and the chance of a re-shoot was going to be minimal so I had to use the conditions I had, which were usually sombre and moody.

‘The further I moved into the project, the more I began to understand which locations would work and in what type of conditions. I also began to work out what type of locations I wanted and in which part of the country I wanted them, instead of having a big list of random ruins. As I shot more and more images I moved away from sunrises and sunsets and instead looked for stormy or overcast days. I looked for what I considered the “right” conditions, which slowed the photographic output as I spent more time waiting and less time shooting.’

Time is one of Landscape’s overarching themes and as you might imagine for a project ten years in the making, there have been highs and lows along the way. However, for every moment of frustration, doubt and loneliness, Jeremy’s determination has been renewed by moments of surprise and delight. ‘I’ve been to some wonderful locations, many that I didn’t know existed and certainly didn’t know the history of, and I’ve met and had help from many strangers along the way, from eccentric hotel owners to dour Scottish farmers. One had a face like thunder and marched aggressively across his field, I assumed to tell me off for trespassing, but he couldn’t have been more friendly and helpful if he’d tried.

Another pleasant surprise was being fed tea and biscuits while shooting a castle from the back garden of someone I had bumped into earlier in the day. As for disasters, well, there’s always the “getting cut off by a rising tide and wet feet” trick, and sitting in motorway traffic jams in the most stunning conditions. The biggest disaster though is probably going to the same location at the same time of year, year after year, only to be told that you’re turning up in completely the wrong season.’

Location, location, location

Location finding, it seems, is not an exact science. Some, such as St Benet’s Abbey in Norfolk, Jeremy was already well aware of, having visited on many previous occasions, while others, such as Warden Point on the Isle of Sheppey, were only vaguely known about or discovered through research or by perusing Ordnance Survey maps. Some, such as the old industrial workings at Rosedale in Yorkshire, were discovered purely by chance and provided him with some of his most memorable experiences.

Dinorwic Quarry, Caernarfonshire. Nikon D850, Zeiss 50mm, 1/8sec at f/11, ISO 64

‘A casual walk with a friend turned into a shoot with epic skies and gorgeous light,’ he recalls. ‘It was rushed, unplanned, unexpected and totally lucky. To shoot a location without being influenced by anyone else has a rather satisfying feel to it.’

Even with his ‘more time waiting, less time shooting’ approach, when it came to selecting the 109 images that would grace the pages of Landscape, Jeremy was faced with a Herculean challenge, as he’d amassed over 500 photographs to choose from. His pragmatic solution was to focus on geography as much as creative intent.

‘The final selection came about through a mixture of wanting my favourite images as well as having a reasonable spread across Great Britain. I also wanted to have a reasonable spread of the type of ruin, from social to religious, military to industrial. Sadly, I’ve missed out some areas such as Orkney, Shetland and Northern Ireland, but I simply didn’t have the time or budget.’

Dunskey Castle, Dumfries and Galloway. Nikon D810, 14-24mm zoom, 2 minutes at f/11, ISO 100

Pulling everything together

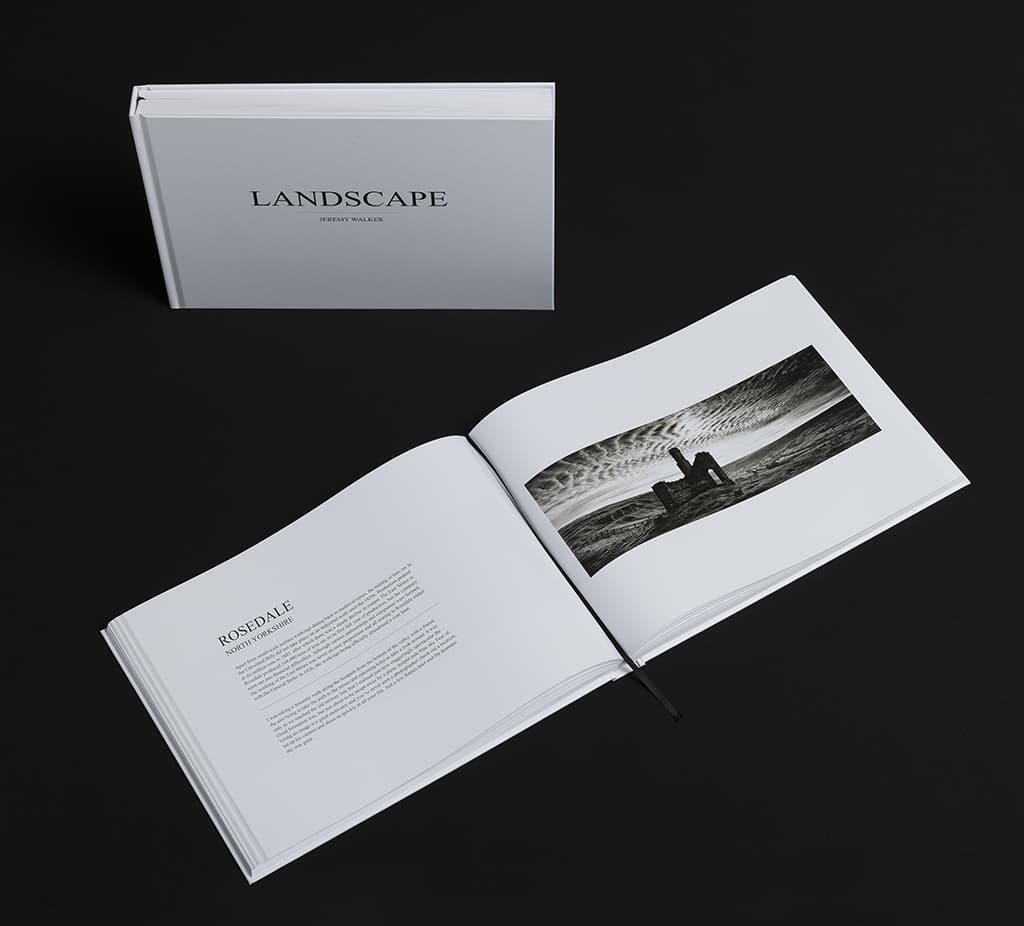

After much deliberation, Jeremy opted to self-publish, a decision that gave him complete freedom when it came to production. However, this wasn’t his original choice. ‘The more I spoke with publishers and, more importantly, other photographers who’d been published, I realised that to produce the book I wanted I needed to be in control. Fortunately, I’ve been supported by a great friend who has publishing experience and he was able to put me in touch with the right designer and printers. Pulling everything together has been a challenge, as will marketing and selling it. If you don’t want stress in your life, don’t self-publish!’

Rosedale Iron Ore Works, North Yorkshire. Nikon D3X, 24-70mm zoom, 1/80sec at f/11, ISO 100

Now that Landscape is on sale – the perfect Christmas present for fans of landscape photography (see below for our special offer) – what are Jeremy’s hopes for the book. ‘My main hope is that I sell every copy,’ he laughs. ‘Apart from that, it’s an ambition fulfilled. I also sincerely hope that it inspires people to explore the British countryside, perhaps even get interested in the incredible history we have. As for a sequel, I’d love to produce another volume along similar lines, and there are other photographic projects in the pipeline as well that will hopefully be turned into print if I’m fortunate enough.’

Warden Point Radar Station, Kent. Nikon D810, 24-70mm zoom, 5 minutes at f/11, ISO 64

Jeremy’s top tips

1) I spend a great deal of time hanging around waiting for storms to clear, hailstones to stop hitting and rain to ease up. By the time said storm has cleared, the light you wanted may have come and gone so you need to be ready and waiting while it’s still raining, snowing or hailing. You may have the appropriate wet weather gear, but what about the camera? In the past I’ve used a chamois cloth covering the camera and lens, held in place by a bulldog clip and it’s worked well. I’ve now upgraded and have a piece of leather, cut to fit around the camera, with Velcro in each corner. It’s simple, effective and quick to use. Perhaps I should patent it?

2) I have covered many locations and much ground while shooting images for the book and one thing I am always conscious of is being on other people’s property. I try to keep to public rights of way, but if I do stray from the path, I like to seek the land owner’s permission. The nearest farmhouse or estate office is a good starting point and not once has a farmer said no to me standing in the middle of a muddy field after explaining what I’m up to. In Scotland the Right to Roam legislation is handy to know about and can be downloaded from the web.

3) Apart from carrying a camera and a handful of prime lenses, one thing I am never without is a couple of ND grad filters. Yes, skies can be tweaked in post-production, but having walked miles in appalling conditions there is something about capturing the final image while on location. Grads allow you to control the exposure of the clouds, but also allow for image interpretation, adding mood and drama when nature needs a little help. I carry just a couple of medium and hard grads as well as a polariser – and occasionally a Big Stopper – and these will cope with most situations.’

4) We live in an age of instant gratification and photography seems to have gone the same way, but many of the images in this book have taken me several years to capture. Persistence, perseverance and perhaps a bit of bloody-mindedness have helped. Returning to locations time after time only to get yet another soaking are part of the location photographer’s lot. If you give up after the first attempt you are not going to get the image you want. Some return visits have been a year or two after I first stumbled upon a location. I keep a database of locations: where it is, what season I first visited, where the nearest accommodation is and so on.’

Jeremy’s Gear

‘My core kit has always been Nikon and I used a D810 to shoot most of the Landscape images with. However, rather than use zooms I tend to shoot with just a handful of primes: Zeiss Milvus 21mm, 35mm and 50mm. I find that primes make you explore while zooms make you lazy. In the later stages of the project I also found myself using a Leica M10. The compact nature of the camera and its lenses were ideal for long walks without lugging a large kitbag around. As with any location shoot there are numerous non-photographic items and bits of kit you need: good boots, waterproofs, Ordnance Survey maps, head torch and sometimes silly things like a soft foam cushion to sit on. You try sitting around on a cold slab of stone in the wind and rain waiting for the light!’

Exclusive offer on Jeremy Walker’s new book

Landscape features 109 images of Britain’s most dramatic ruins across 232 panoramic pages. It costs £45 from his website but Jeremy is offering signed copies exclusively to AP readers for just £35 plus p&p.Visit here to order a copy at this special price. Offer closes at midnight on 24 December 2020.

Further reading

How to photograph black and white landscapes

Essential tips for winter landscape photography