We all like to assume photography and cameras are a good, positive thing in our lives, but of course, they can be used for sinister purposes too – particularly state surveillance.

I got a stark reminder of this recently while visiting the Stasi museum in Berlin – ‘Stasi’ being an abbreviation of the Ministerium für Staatsicherheit, the state security service of communist East Germany from 1950 to 1990 (when it thankfully collapsed, along with the Berlin wall).

What set the Stasi apart was the incredible effort it made to keep tabs on the East German population, via tens of thousands of employees and a vast network of informers. The idea was to identify discontents and potential protesters long before anyone actually took to the streets, and deal with them accordingly.

Citizens were encouraged to snoop on each other and report back anything that went against the party line, right down to your neighbour or colleague liking ‘imperialist’ fashion or music (one poor soul got two years in prison just for writing a pamphlet about the East German punk scene).

The Stasi’s tentacles crept into workplaces, churches, sports clubs and families, and it is estimated that at its height, a staggering 2 out every 100 East Germans had some kind of Stasi connection. It had an international reach too, with its famous spymaster, Markus Wolf, being one of the inspirations for the ‘Karla’ character in John Le Carre’s classic espionage novels.

Monitoring the Lives of Others

There’s not time in this article to recount the long, grim history of the Stasi – there is tons of information online, and the movie The Lives of Others brilliantly captures the paranoia and moral shabbiness of the era.

But if you find yourself in Berlin – a highly photogenic and richly storied city, to put it mildly – the Stasi museum gives a unique insight to the organisation. It’s housed in the perfectly preserved former offices of the Stasi’s notorious boss, Erich Mielke, and the museum does a great job of revealing how cameras were an integral part of his goons’ toolkit.

Some 1.75 million photos and 2,800 movie reels were shot by the Stasi, and the use of cameras ranged from the sinister to the comic, so keep scrolling for more!

A popular tool of the trade was the Soviet-made F-21, above, first commissioned by the KGB in the 1950s. The F-21 was so small and light, it could even be hidden behind a button.

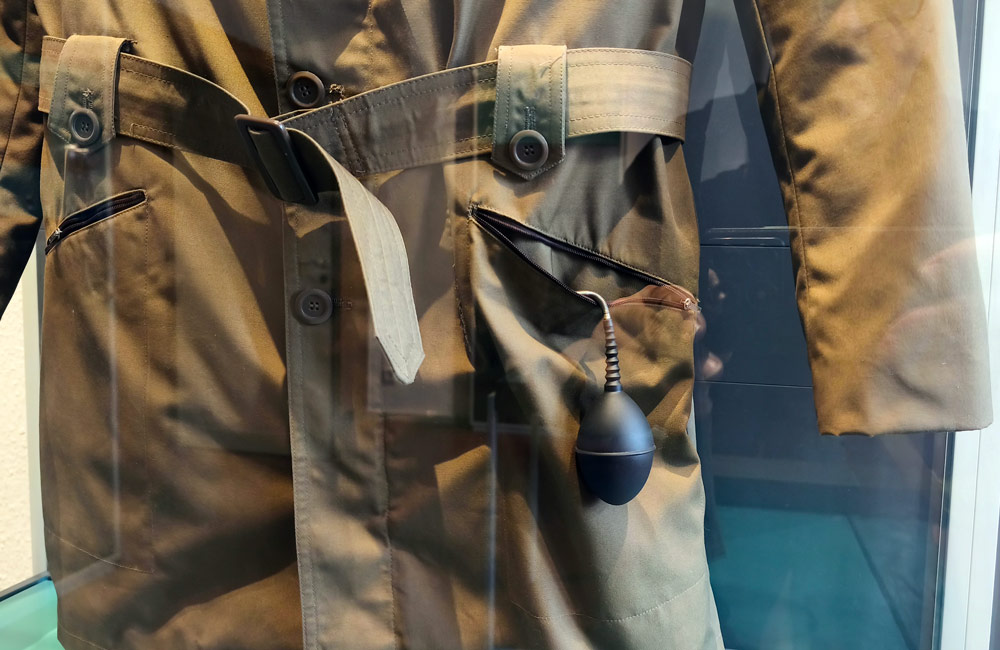

This shows a Stasi jacket with a hidden camera – the camera release sat in the jacket pocket and could be operated without drawing attention.

The Stasi began buying Robot cameras from West Germany in the 1960s. These were adapted for covert photography, with the noise of the film transport dampened and ingenious remote triggers fitted.

The Stasi also made full use of the Totscka camera; again first developed by the KGB, it was basically a copy of the West German Minox. Wallets were another popular hiding place for miniature cameras.

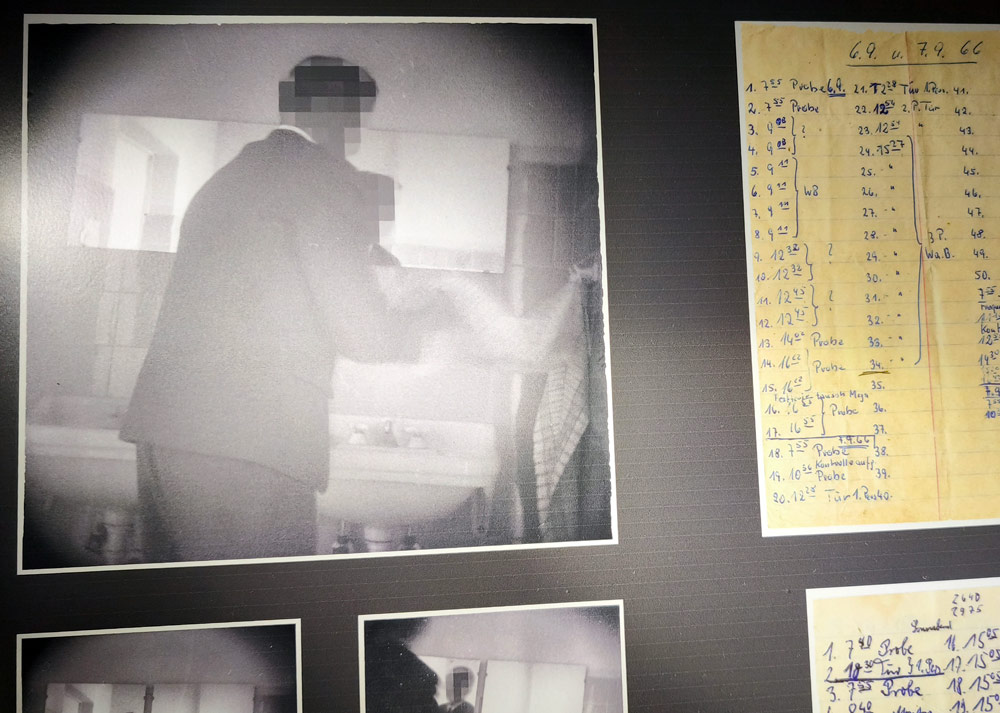

The Stasi perfected the use of pinhole lenses (above) to record particularly ‘interesting’ subjects. These lenses were hidden in a wide range of buildings, including offices, factories and private apartments. A hole was drilled in the wall and the lens pushed through – an opening of 1mm was all that was needed to photograph or film what was going on in the room. Movies were recorded too, again via concealed devices.

Washrooms and watering cans…

Erich Mielke, the long-serving head of the Stasi, was just as paranoid and information-hungry as his US counterpart, FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, despite being poles apart politically.

Mielke even had a pinhole lens put in the wall of the toilets next to his office so he could check what visitors were up to (beyond the obvious, one assumes).

Belts and jackets are one thing, but some Stasi functionary with a taste for gardening came up with the wheeze of concealing a miniature camera inside a watering can (it had a separate compartment at the top).

The prize for the most extreme concealment must go to this elaborate car-door camera, however. An infrared flash system was put in the door of one of East Germany’s ubiquitous Trabant cars.

Thirteen infrared rays were simultaneously released to generate the flash, which was invisible to the human eye. An image was then captured by a GSK SLR and Carl Zeiss Jena rangefinder lens and recorded on Kodak infrared film bought from the west.

The cost and complexity of this set-up meant it was only used on special occasions, however.

‘Hello this is the Stasi, we’d like to buy some cameras…’

For general photography of suspicious people and activities, the Stasi starting using SLRs in the 1960s, for the same reason that they are still popular today – a relatively compact size and lots of interchangeable lenses. Favourites included the Ihagee Exakta 500, VEB Pentacon and Praktica models.

The Carl Zeiss Jena factory was a two hour drive from the Stasi HQ, so the company was called upon to provide high-quality lenses.

More modern camera technology was fully utilised, too. What made the Stasi so sinister was the way it intruded into the lives of the population, often to undermine the morale and mental health of ‘undesirables’ in subtle and not-so-subtle ways.

Polaroid cameras were frequently used to record the results of apartment searches, with the victims rarely suspecting the Stasi had gained entry (they were genius lock pickers).

Last but not least, the Stasi fancied themselves as masters of disguise, though the results often look comical to modern eyes. Above, a Stasi flunky shows how to pass yourself off as a tourist once you have left the workers’ paradise.

The Stasi are gone – state surveillance certainly hasn’t

It’s easy to look back on the Stasi as a particularly nasty relic of the Cold War, but its legacy has been embraced by modern states eager to keep on eye on the masses. Modern technology has enabled the Chinese Communist Party, for example, to take mass surveillance to a whole new level, without worrying about cameras in car doors and watering cans. And let’s not forget that Russian leader Vladimir Putin was a card-carrying member of the Stasi as well as the KGB.

The Stasi Museum is a short walk from Magdalenestrasse station on the Berlin subway (U5), easily accessed from the central train station. The extensive Stasi HQ buildings are all still there, and as well as the main museum, there is limited public access to the Stasi records archive – put in a line, the meticulously organised and updated files would stretch nearly 70 miles!