Sony’s headquarters in Tokyo, Japan – Sony Alpha 9

Sony’s Alpha 9 is without doubt one of the most exciting cameras of the year. It’s a high-speed, full-frame, mirrorless model that challenges, and in many ways surpasses, pro-DSLRs in the last bastion of their superiority, namely sports and action shooting.

On a recent trip to Japan and Thailand with Sony Europe, I was lucky enough to receive a rare insight into the thinking behind its design, and the state-of-the-art manufacturing facilities that make it possible.

It’s easy to forget, but Sony is a relatively recent player in the interchangeable-lens camera market. It began by acquiring Konica Minolta in 2006, with its first genuinely homegrown DSLR being the Alpha 700 in 2007. But the most significant milestones in its progress have been the introduction of the mirrorless E-mount in 2010, followed by the full-frame Alpha 7 system in 2013. Since then, the firm has gone from strength to strength and broken Canon and Nikon’s duopoly on the high-end professional market. Sony now claims to be the market leader in terms of mirrorless camera sales in Europe, and second for sales of full-frame cameras behind Canon (at least before the launch of the Nikon D850).

Along the way, Sony has shown a serious appetite for innovation, repeatedly gambling on making new types of camera that haven’t been seen before, in the hope of stimulating an often moribund-looking camera market. But its relative inexperience also shows, with its cameras often being less well-rounded packages compared with its main competitors, particularly in terms of handling. It also doesn’t seem to have established the same kind of emotional connection with its users that’s been achieved by the likes of Fujifilm, whose commitment to continually improving existing models via major firmware updates has established a fiercely loyal following. In contrast, Sony can give the impression of being a faceless electronics giant, brilliant at squeezing advanced technology into tiny camera bodies but less good at understanding what photographers really want from them.

Perhaps in a bid to overcome this perception, the firm recently invited a group of European photographic journalists on a tour of its head office in Tokyo, its giant sensor-production factory in Kumamoto, and its camera and lens plant near Bangkok. Along the way, we spoke to senior managers and engineers, and gained rare behind-the-scenes insight into the thinking behind its operations.

Golden Pavilion, Kyoto, Japan Sony Alpha 9, Tokina Firin 20mm f/2 FE MF, 1/320sec at f/8, ISO 100

Tokyo – the nerve centre

If there’s one place that counts as the birthplace of Sony’s cameras, it’s the firm’s corporate headquarters in the Shinagawa district of Tokyo. This is where senior managers devise the core concepts behind new products, and engineers work out how to overcome the technological hurdles involved in bringing these ideas to fruition. Along the way, they work closely with the sensor experts in Kumamoto, aware well in advance of all the new technologies that are in development, and pushing the sensor engineers into getting the most possible out of them.

In the case of the Alpha 9, the intention was to produce a mirrorless camera optimised for shooting sports and action. In technical terms, this was distilled down to a deceptively simple-looking design brief – how to build a camera capable of shooting at 20 frames per second with a zero-blackout viewfinder, while taking focus and exposure readings, and viewing the live view feed at 60fps. But

to achieve this, all of the camera’s core components had to be designed from scratch – including the viewfinder, image processor and the stacked CMOS image sensor.

Indeed, it’s the sensor, and its layered design, that really makes the Alpha 9 possible. Its backside-illuminated architecture captures as much light as possible, but far more importantly, it permits the addition of a large amount of on-chip memory and a high-speed digital image processing circuit. This, ultimately, is what allows the camera’s high-speed, low-distortion shutter and super-fast shooting rates. It’s clear that Sony’s ability to make its own sensors and seamlessly integrate them into new camera designs gives it a real edge over its competitors. Other manufacturers can do similar things, for sure, but none can manage quite the same combination of high image quality and outright speed.

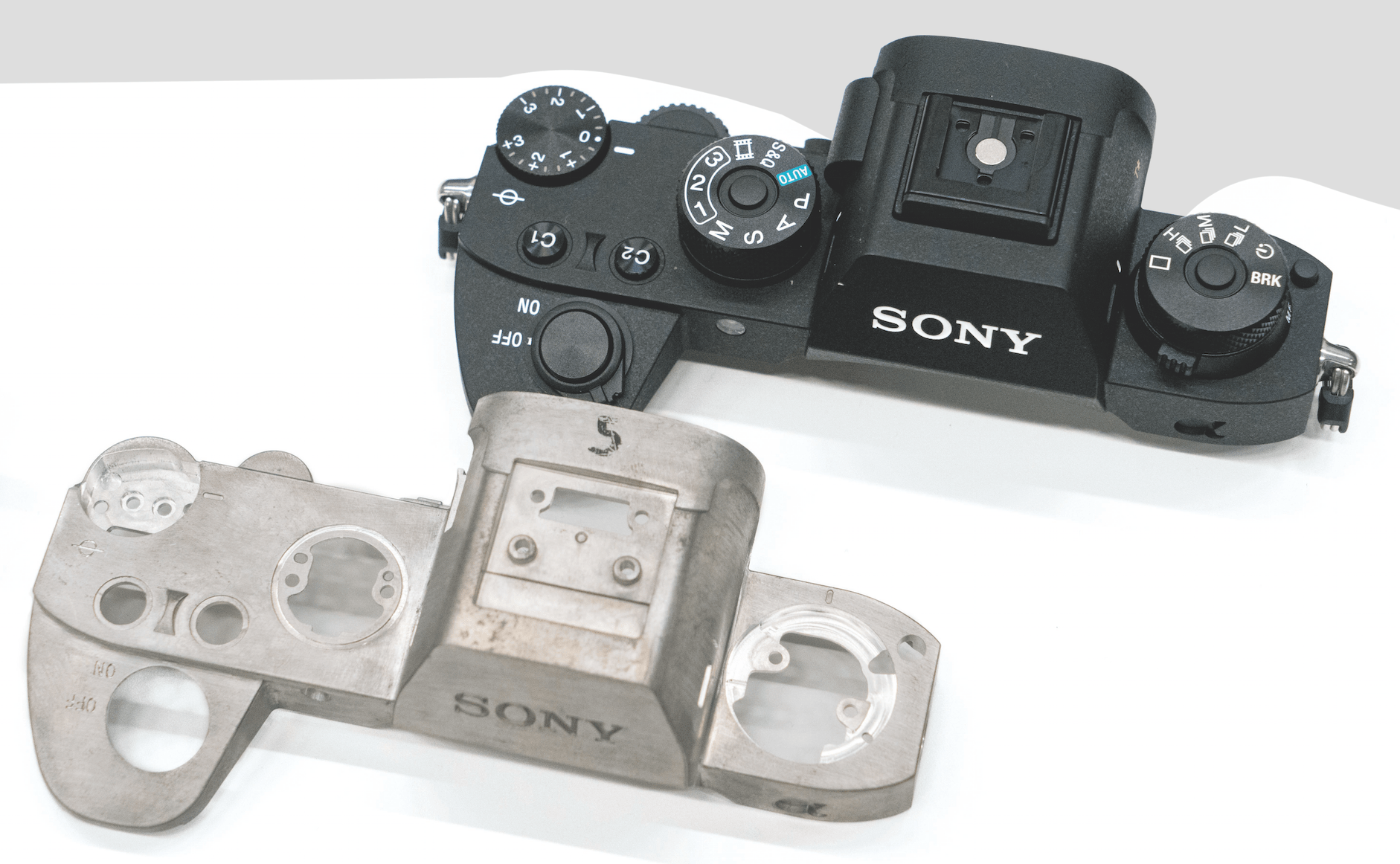

Sony Alpha 9 top plates, unpainted and finished

It’s not just the sensor, though; the Alpha 9’s viewfinder panel is also purpose designed and homegrown. Indeed, it’s made in the same factory as the sensor, using a lot of the same technology and production processes. It employs a white electroluminescent panel

with a colour filter overlay that combines high brightness and contrast, a wide colour gamut and rapid response times, all in a small form factor (the panel itself measures just 7.5x10mm). It’s clear that Sony considers this display to be just as crucial to the camera’s abilities as the sensor.

The final piece of the jigsaw is the camera’s firmware and, in particular, its autofocus algorithms. Here, Sony worked closely with professional sports photographers, running through multiple cycles of assessing images shot with prototype cameras, analysing any focus errors and then rapidly addressing them with new firmware in time for a new round of testing. After six months of intensive field testing and iterative improvements – far more than for any previous Sony camera – the Alpha 9 was ready to go to market.

Continues after…

[collection name=”small”]

Mirrorless for action

Despite the rapid improvement of mirrorless cameras, many photographers have assumed that DSLRs would remain the first choice for sports and action due to their sophisticated phase-detection autofocus systems. But Sony thinks very differently. Its engineers described with impressive clarity why they believe mirrorless cameras to be better suited to high-speed photography, and explained

how their vision is realised in the Alpha 9.

First, though, we need to think about how DSLRs work. In essence, they developed directly from film cameras, with a digital sensor replacing the film, which means that it’s kept in a light-sealed box until the moment of exposure. Focusing and metering, therefore, require a complex system of optics and secondary sensors. A semi-silvered mirror directs most of the light from the lens to the viewfinder, with the rest being deflected downwards by a secondary mirror to an autofocus sensor in the base of the camera. Light metering requires yet another sensor that’s located in the viewfinder assembly. To make an exposure, the mirror flips up and the shutter opens, in the process blacking out both the viewfinder and the autofocus sensor.

Sony’s vast sensor factory in Kumamoto, on the island of Kyushu, Japan

This design has certain inevitable consequences. Autofocus measurements can only be taken when the mirror is down and stable, meaning that the camera has to predict where the subject will be when the exposure is actually made, based on readings taken a fraction of second earlier. But when the subject is moving erratically, this can lead to focusing errors. The proportion of the image that can be covered by the autofocus sensor is also limited by the size of the sub-mirror, particularly on full-frame DSLRs where it’s less than half of the frame height. If the subject moves outside this area, the camera can’t focus on it.

In a mirrorless camera, however, composition, autofocus and metering all utilise the main image sensor directly. This brings a range of advantages: the camera is able to autofocus accurately anywhere in the frame, while keeping track of subjects as they move around it. By using an electronic shutter, the sensor can also be kept exposed to incoming light all the time, giving a zero-blackout viewfinder that makes panning with moving subjects much easier. What’s more, it’s possible for the camera to take focus measurements continually up to the moment of exposure (at a rate of 60 per second, in the case of the Alpha 9), allowing it to pinpoint the subject’s exact location when the shutter is released.

This might sound like Sony’s engineers rationalising their pet product, but having used the Alpha 9, I’m convinced they are correct. Its ability to pick up a subject anywhere in the frame and hold focus on it while shooting at high speed is uncanny, and all made possible by the zero-blackout design. The fact that the camera makes lots of small focus adjustments during continuous shooting, rather than one larger movement per frame, also seems to help in giving extraordinary autofocus accuracy. The Alpha 9 isn’t perfect, but it gives Canon and Nikon’s top-end models a serious run for their money, which is remarkable given that it’s Sony’s first attempt at a pro-sports mirrorless camera. It’s anyone’s guess how far ahead Sony will be after another generation or two of development.

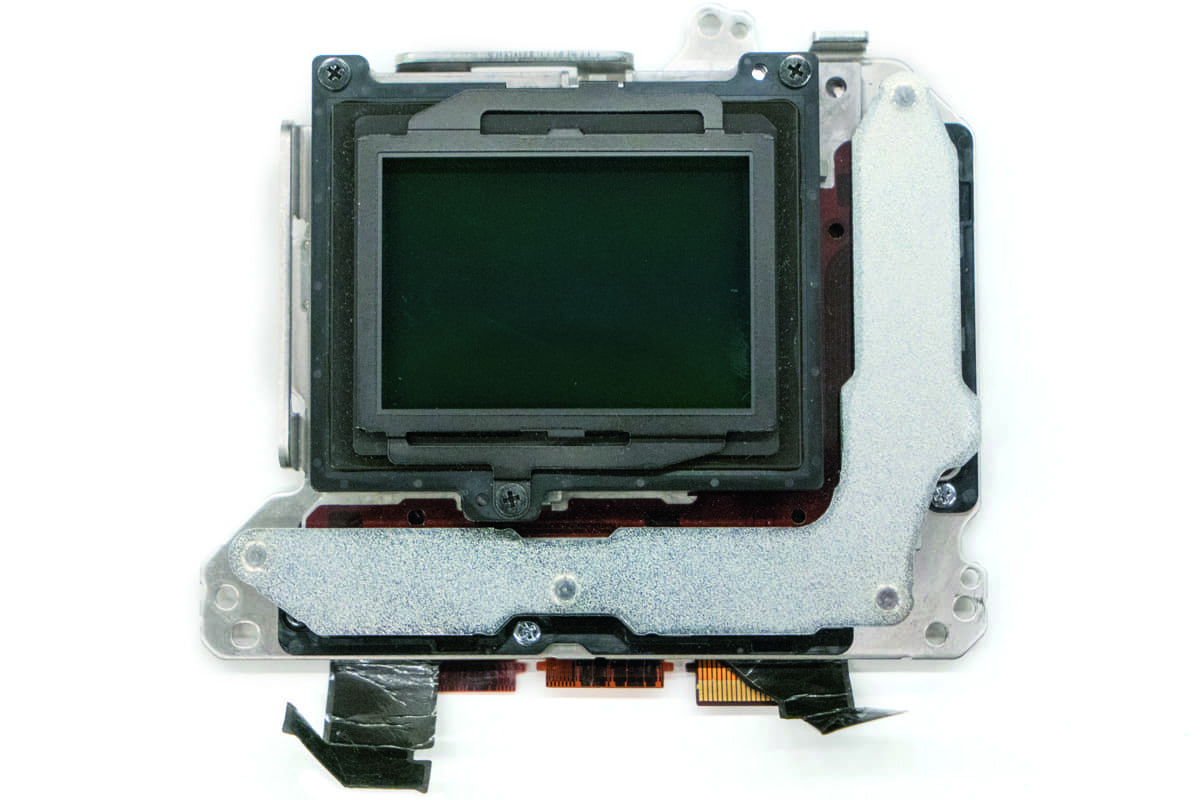

Sony Alpha 9 sensor assembly

While the vision and skill of Sony’s hardware engineers is beyond question, I do have some doubts about the coherency of the firm’s overall approach. For example, the camera-design team repeatedly stressed how important they felt it was to make the Alpha 7-series and Alpha 9 bodies as small as possible, to maximise their size advantage relative to the competition. But the lens designers clearly have no such objective, so routinely produce huge optics such as the FE 24-70mm f/2.8 GM that negate this advantage. The camera designers also seemed somewhat taken aback by suggestions that the Alpha 9 would be a better fit for its role if it were made larger, to make it easier to use with gloves and better-balanced with larger lenses.

Likewise, when asked about firmware updates to fix the Alpha 9’s most obvious operational flaws, Sony’s engineers were unprepared to make any specific promises. But to be fair, the firm has a decent track record in this regard; for example, it’s steadily improved the Alpha 7 II over its lifespan, most recently with firmware version four in August when the camera was almost three years old. Hopefully, it will do the same for the Alpha 9, listening carefully to user feedback along the way.

On systems and lenses

One of the more interesting discussions we had with Sony’s product management team related to its priorities regarding lens development. The firm has two lens mounts on the go – the legacy Alpha mount inherited from Minolta used in its SLR-like models, and the mirrorless E-mount – and makes both full-frame and APS-C sensor cameras with each mount. But since the launch of the full-frame mirrorless Alpha 7, it’s concentrated on making FE lenses to match, with no new APS-C lenses and just a couple of updated A-mount optics. The firm’s explanation for this is that it simply reflects the state of the market: full-frame users are typically serious amateurs or professionals who buy more lenses and demand a wider range of options than APS-C shooters. Therefore, Sony is sensibly focusing its efforts where the demand for new lenses is strongest and it will make the most sales.

After assembly, each camera goes through a series of tests. This appears to be a lens-drive test

So while nobody in the company is ever going to talk about upcoming, but as yet unannounced products, it’s the surest bet imaginable that over the next year or two it will concentrate on releasing high-end long telephotos matched to the Alpha 9. Despite this, Sony is adamant it doesn’t consider its APS-C E-mount lens range to be complete, and expects to revisit it in future to add some more interesting optics. However, the prospect of new lenses for Alpha-mount users seems more remote; instead, the firm plans to provide updated SLT bodies from time to time. Don’t expect to see a Sony medium-format system appear any time soon, either.

Kumamoto – world of sensors

From Tokyo we travelled to the city of Kumamoto, some 550 miles west and to the south, on the southernmost of Japan’s main islands called Kyushu. It’s a hub of Japan’s semiconductor industry, thanks to a plentiful supply of very clean water and relatively low labour costs. Surrounded by beautiful countryside, it feels like an unlikely location for Sony’s vast sensor manufacturing plant that’s one of the most advanced in the world.

The sheer scale of what goes on here is mind-boggling. Its two huge buildings include six floors of clean-rooms, in which environmental contaminants are kept to a strictly controlled minimum. Sony told us the plant outputs four million image sensors every single day, and while most are surely destined for use in mobile devices, this is also where the sensors in most digital cameras come from. If you own a compact camera with a 1in sensor, any Sony camera, or indeed almost any recent model from another manufacturer, this is most likely where its sensor was born. The main exception is Canon, which makes all its own sensors for its EOS cameras.

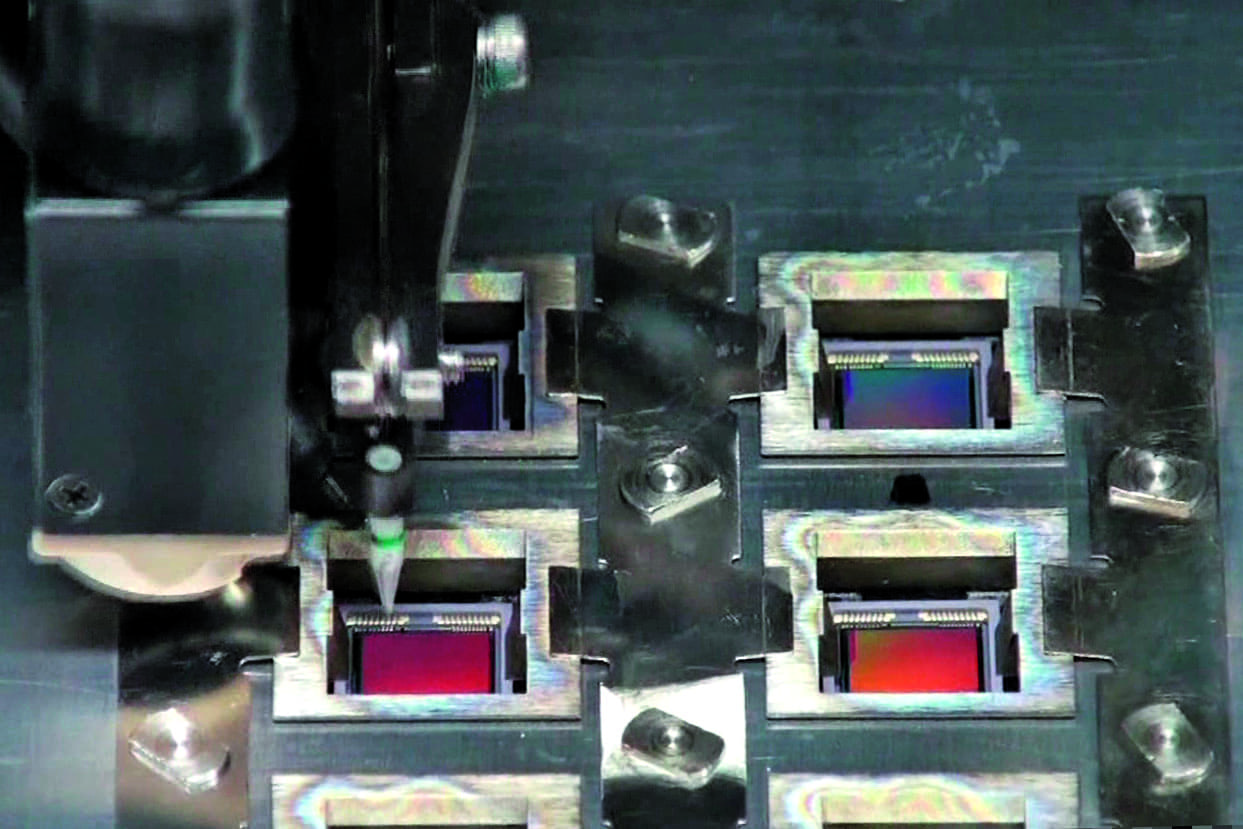

Here sensors are being bonded to their logic boards

The factory is an exceptionally high-tech environment in which sensor production is almost entirely automated. It employs 2,700 workers but they mostly seem to inhabit the office space. Only a few prowl the clean-rooms in their all-over body suits, and their role seems to be restricted to identifying and troubleshooting any problems that may occasionally arise. But mostly, the machines are left to get on with their tasks, fed by automated component carriers that move along tracks suspended from the ceilings.

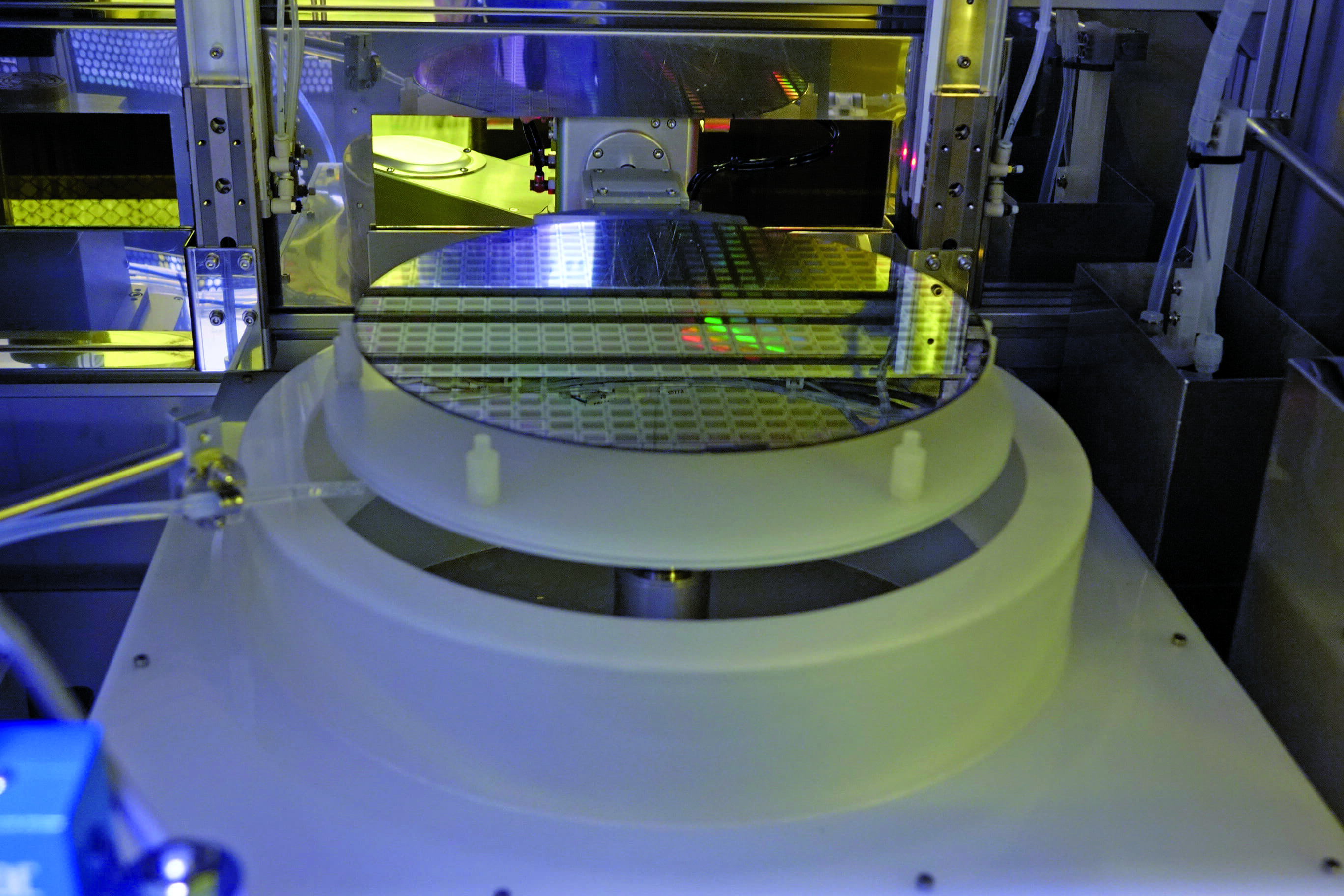

Producing the sensors is a complex process, with steps that include photolithography,

ion implantation, dry etching, physical and chemical vapour deposition, electrochemical deposition, cleaning and polishing, and oxidation and annealing. The whole process takes a surprisingly long time: up to six months from a silicon wafer arriving in the factory to finished sensors leaving, in the case of the complex stacked CMOS chips used in Sony’s latest models including the Alpha 9. These sensors are therefore also the most expensive to produce, and it says a lot about Sony’s technology-driven approach that it’s been prepared to go to such lengths to gain a competitive advantage. It also goes some way to explaining why its latest-generation cameras are so much more expensive than the previous models.

Recovering from an earthquake

In the early hours of 16 April 2016, Kumamoto was hit by an earthquake of magnitude 7.3. It caused considerable structural damage to the Sony factory, destroying manufacturing equipment and halting all production. Pictures from the aftermath show shattered wafers of part-made sensors, equipment scattered across clean-rooms, and even roofs ripped open to reveal the sky above. As a result, camera production was set back considerably, not just Sony’s but other manufacturers’, too.

Despite the scale of the damage, Sony put in place a Herculean effort get the factory working again. Engineers donned hard hats and cleaned up the mess themselves, carefully setting aside undamaged manufacturing equipment and materials. Fewer than five weeks after the earthquake, production restarted and the factory had fully recovered within three-and-a-half months. The physical scars of the experience are still visible today; numerous sections of the walls along the corridors are painted a slightly different colour where cracks have been patched up. Sony claims that if a similar quake were to happen in the future, it has put in place extra measures that mean it should be able to recover in just two months.

Chonburi – building the Alpha 9

While Sony’s product design and sensor manufacturing are both done in Japan, its cameras and lenses are now mostly made in Thailand. Here, Sony says it can employ skilled labour at a much lower cost than in Japan, while still maintaining the high level of quality that’s essential for professional-level kit. Sony Technology (Thailand) Co Ltd has two main factories, with cameras being made in its Chonburi plant that’s located an hour’s drive to the east of Bangkok. This location boasts excellent air and sea transport links, ideal for bringing in parts and materials, and exporting finished products. Not only does the factory assemble both cameras and lenses, it also manufactures the complex, miniaturised circuit boards inside.

The Sony Alpha 9 assembly line in Chon Buri, Thailand

The factory started out life fairly unambitiously, making consumer-level products such as the 18-55mm zooms sold with DSLRs and some of the early NEX mirrorless cameras. But as its experience increased, Sony pushed it harder, getting it to build increasingly higher-end, more complex items. As a result, it’s become a highly accomplished outfit, able to produce the most technically demanding items in Sony’s range, including all of the top-end Alpha models and most of the G Master lenses. The latter are assembled in clean-rooms, with workers rigorously suited up in overalls, face masks and hair nets.

The environment for final assembly of the cameras is a little less stringent, and we were granted rare access to the Alpha 9 production line, and even allowed to take pictures. It’s a surprisingly labour-intensive process, with long lines of young Thai men and women, each carrying out a single step that they’ve been trained and certified for. As parts move along the line, the camera gradually builds up to a finished whole, before undergoing a whole raft of checks and tests. Finally, it’s boxed up with all of its accessories for shipping.

Final thoughts

So at the end of all that, what have we learned? As we made the gruelling 12 1/2-hour flight back to Heathrow from Bangkok, I certainly found myself impressed by Sony’s technical ingenuity, the vision of its engineers and the commitment of its factories to attaining the highest possible standards.

Sensors being cleaned and polished, before being diced from the processed wafer

But on the other hand, it did little to allay the impression that the firm is driven almost entirely by the lure of stretching the limits of what is technically possible. During our week in Japan, relatively little was said about the art of photography, or of listening to feedback from real photographers and working to address their needs or desires.

Of course, when this approach pays off, Sony is capable of delivering truly groundbreaking products such as the Alpha 9, which allow photographers to capture images in ways that simply weren’t possible before. But it also explains the firm’s habit of cramming more and more features into its cameras, while not addressing any of their more evident design flaws. Sony is clearly going to be a considerable player in the camera market due to its sheer technical cleverness but if it could only come to trust photographers and genuinely learn from their feedback, it could surely become the single most dominant player for the foreseeable future.