Unless you have been cohabiting with a hermit in Bhutan over the last 18 months, you will have seen how AI is now being widely used to make editing images as easy as possible, particularly when it comes to removing background distractions.

Just recently, for example, Apple added the Clean-up Tool to iOS 18, which can identify and remove distracting objects in the background of a photo without accidentally altering the subject. This follows on from the Google Magic Eraser tool, which uses AI to let you edit and replace the sky, remove and move objects, as well as adjust other settings.

Easy sky replacement and object removal has also been a staple feature in AI-powered photo-editing software for a while.

All well and good, but I am not convinced that much of this hand-holding technology is actually making us ‘better’ photographers; rather, I worry that it could just making us lazier ones.

Now, I am the first to scoff at luddites who claim that all digital photo-editing is somehow cheating, and that photography was somehow more pure back in the film days. Usually those making such claims do so because they don’t understand how to use photo-editing programs properly, or have big gaps in their knowledge of the history of photography.

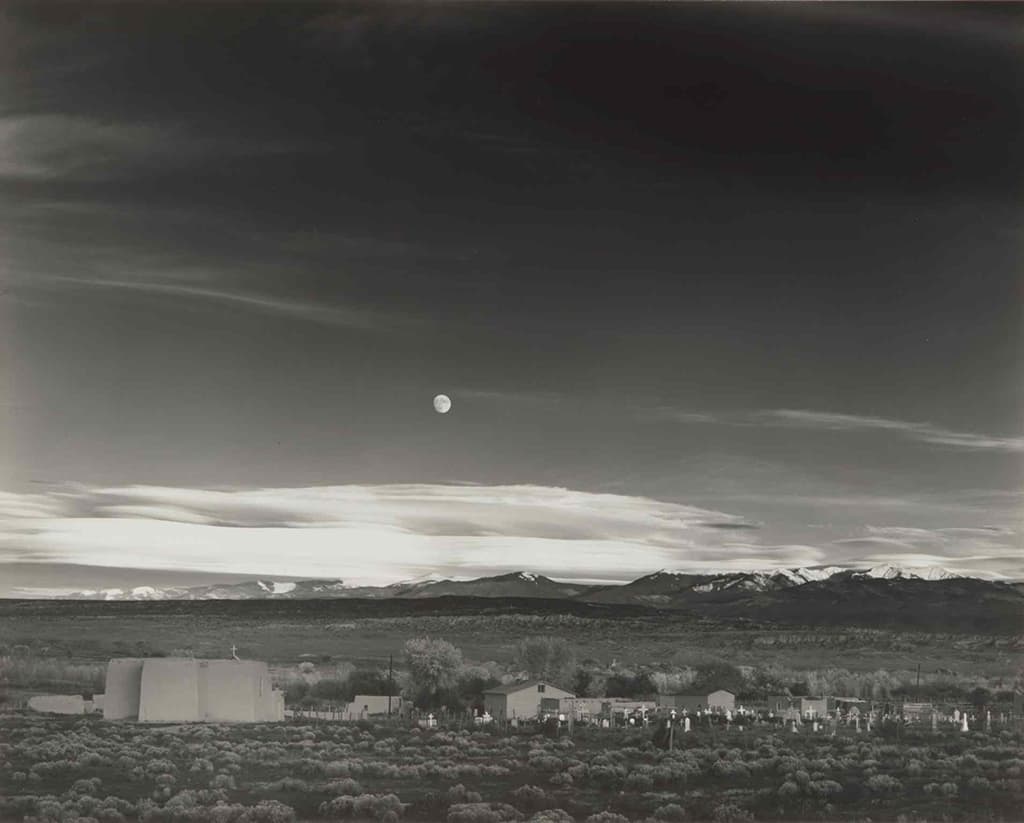

Ansel Adams is the most obvious counter-example. While a master of exposure and composition, he definitely ‘worked up’ the drama in his images, using darkroom dodging and burning techniques. As far back as Victorian times, photographers touched up images (see this excellent article from the Smithsonian magazine).

My particular concern is that the proliferation of all these AI assistants today will just make a lot of us complacent. As any serious landscape, sports or news photography will tell you, good photography is often quite difficult.

You have to get up early to get the right light, or be prepared to get wet and cold to get the best vista. Meanwhile, the best documentary and travel photographers develop an almost uncanny ability to ‘sense’ when something big is about to happen (often through bitter experience of missing shots), and prep their gear accordingly.

These are perhaps extreme examples, but rather than relying on some AI tool to remove distractions in the background, why not spend an extra few seconds composing the shot to ensure that the distractions don’t creep into the frame anyway?

This is surely good for your composition skills generally. Sometimes it’s not possible with a grab shot, but usually the photographer can reposition themselves or try a different angle. We shouldn’t be relying on AI to make us better at composition.

The same goes with a boring-looking sky. There are times that landscape photographers, for example, just have to ‘suck it up’ and return to the same spot on a different day as the weather/light has suddenly changed for the worse. When you finally get the result you want, surely this is more satisfying than adding in a different sky on the computer?

Such technology can certainly be handy if you aren’t able to return to that beauty spot (maybe it’s the last day of your holiday, for example), but otherwise, taking the easy way out lessens your involvement in the final picture.

Some of my best pictures were quite challenging to take, and my blood, sweat and tears are in the very DNA of the shot (well, if not my bodily fluids, at least my frustration, aching shoulders and sore feet).

OK computer, where’s the connection?

To give another example: yes, it’s not hard to generate an AI picture of a person, but you know what, you weren’t there, they weren’t there, and there was no connection between anyone. The dead-looking eyes in a lot of AI-generated portraits often inadvertently reflect this.

Bokeh is another example. While I enjoy experimenting with the faux-bokeh effects on my smartphone, it’s not like the enjoyment I get from the more authentic bokeh created by a vintage lens (especially if I picked it up cheaply).

I have been reminded of all this recently as I borrowed a 1950s vintage Leica M3. Everything about this camera requires thought and effort: the fiddly film-loading process, setting the film speed and exposure, focussing properly, remembering to wind-on the film, rewinding the film at the end of the roll and fishing it out properly. And then you have to get the film developed before you even have a picture to look at or share.

Sometimes it’s felt like I am trying to play a set of medieval bagpipes – just getting anything out of the camera at all will be an achievement, never mind a decent shot.

But I do know that when I’m happy with an image from the M3, it will have been way more rewarding and educational than taking a sloppy shot on my phone and then trying to salvage/improve it with an ‘assistant’.

It really makes you appreciate the camera-handling skill of famous M3 users such as the legendary documentary and travel photographer Cartier Bresson, but they weren’t born with that skill, they learned it through practice.

While I am certainly not saying that all ‘proper’ photographers should use 70-year-old manual film cameras, phone makers and software developers should also not assume that their mission is to make things completely idiot-proof for photographers, either – or indeed, that this is what the market always wants.

A lot of younger photographers now seem to be coming back to quite complex conventional cameras, and the film photography revival is here to stay. This is not happening because today’s photography is somehow too ‘difficult,’ and that even more hand-holding is needed. As someone who cares deeply about the future of photography, I’d say exactly the opposite.

We also need to bear in mind that a lot of these extra assistants are being piled on for marketing reasons, to give a manufacturer something to shout about at the expense of its competitors. Visual creativity needn’t be a masochistic process, but it shouldn’t be too easy, either.

Further reading

How to get started in film photography

Improve your landscape photography