Picture the scene. It is a dull Monday morning as a man crosses Vauxhall Bridge in London on his way to work. All appears normal to Chris Follows. But 15 December 2014 would turn out to be anything but routine.

This passer-by was about to witness a breaking news event. Luckily, he was carrying a camera phone and was equipped for the job.

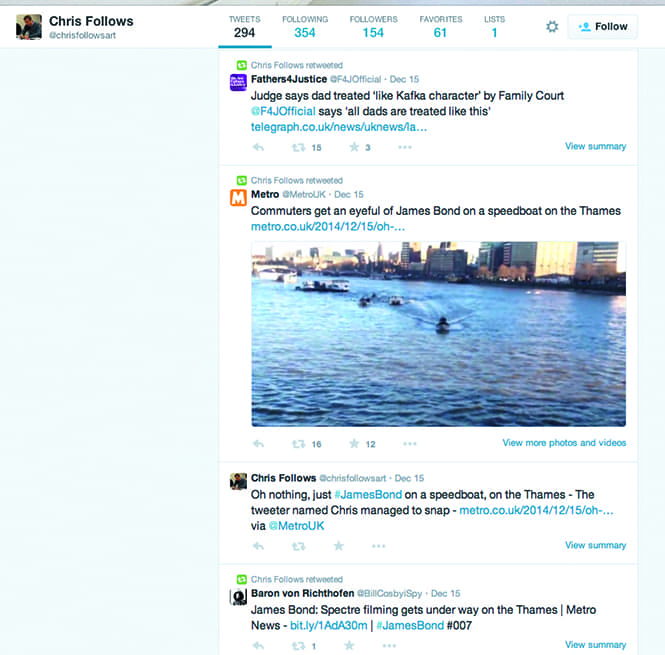

Chris spotted a speedboat looming into view from the murkiness of the River Thames. A colleague quipped that James Bond may be at the helm, the scene being close to the Secret Intelligence Service building MI6. To the pair’s astonishment, actor Daniel Craig then appeared in full Technicolor – as James Bond.

Chris quickly reached for his iPhone and managed to grab a video as the boat passed underneath the bridge.

Chris Follows spied James Bond actor Daniel Craig, and used his camera phone to shoot a video featured on news websites [Photo credit: Chris Follows]

The spur-of-the-moment clip turned out to be some of the first footage of the making of upcoming Bond film Spectre, especially newsworthy at the time, because of reports of a script leak after a cyber attack on computers at Sony Pictures.

Chris promptly uploaded the video to YouTube and tweeted the link, which was gobbled up by the Metro newspaper and Newsflare, a UK-based citizen journalism website.

The footage then appeared on other news websites, yet Chris says he did not receive payment, nor did he seek any, telling Amateur Photographer (AP) he was simply keen to share his news and watch the public reaction play out online. He was happy just to get a credit.

‘It was not something I was particularly looking for. It just happened… The reaction was fantastic,’ he says.

‘I like putting my stuff out there. If it’s on social media, it’s up for grabs, in my opinion.’

And therein lies the insidious threat for some professional press photographers, who fear that the media’s use of free images puts their jobs at risk.

Although Bond’s derring-dos are not exactly ‘hard’ news, on-the-scene smartphone photos document world events like never before.

They are responsible for breaking some of today’s biggest international stories, and bolstering others, including the 2005 bombings on London transport and the Arab Spring uprisings.

Documenting civil upheaval is no longer the preserve of mainstream media, as protesters turn their cameras not only on fellow demonstrators, but also towards those in power, holding authority figures to account in conflict zones where access for traditional journalists is restricted, or simply too dangerous.

After the toppling of the Hosni Mubarak regime in Egypt in February 2011, Hani Shukrallah, former editor of news website Ahram Online, took part in a panel discussion on freedom of expression and the press, in Cairo.

‘It’s the new media, the people’s media, that exposes the truth,’ he said during his address, which was covered by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Malek Blacktoviche, a former IT worker from Aleppo, Syria, has spoken of how he is regularly spurred into documenting the country’s civil war using his digital camera. His work begins at the sound of explosions.

‘I run as fast as I can towards the place where the bombs struck. I capture photos and film the devastation and the deaths,’ he told opendemocracy.net.

‘Amateur Photographer’ reader Chris Dixon took this shot of an arrest in London. ‘As this scene unfolded before our eyes, it generated a multitude of images taken by a group of amateurs meeting in London,’ says Chris [Photo credit: Chris Dixon]

Others are on the scene more as a bystander than in response to a pre-planned journalistic mission.

In 2009, Christopher La Jaunie, a banker, captured vital footage of what turned out to be the crucial final moments in the life of newspaper vendor Ian Tomlinson, who died after being pushed to the ground by police during the protests against the 2009 G20 summit in London.

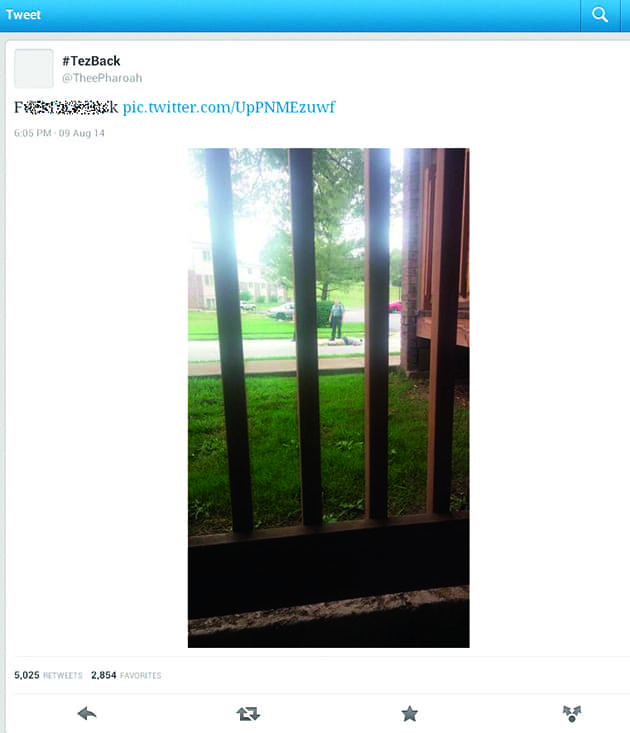

Similarly, during last year’s unrest in Ferguson in the US, Thee Pharoah, a singer, witnessed the murder of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown and immediately posted a photo on Twitter.

Singer Thee Pharoah witnesses the death of unarmed teenager Michael Brown during the Ferguson riots in the US

More recently, a video of the cold-blooded murder of policeman Ahmed Merabet outside the Charlie Hebdo magazine offices in Paris was uploaded to Facebook by Jordi Mir, an engineer.

Social media revolution

Citizen journalism is not new, but the internet revolution has fuelled its potential, the relentless clamour for news images and video reaching fever pitch with the immediacy and accessibility of social media.

The trend has spawned dedicated online services, including photo app Scoopshot, which the London Evening Standard newspaper used to aid its coverage of the Tour de France in 2014, for example.

Gareth Vipers is an online editor at the Standard – one of 70 organisations worldwide regularly using content provided via the Finland-based app.

‘Twitter has transformed the way we approach news, in the same way as [the paper’s] interaction with our readers – who are often on the scene of a story before we are,’ he says.

‘Scoopshot has enabled us to access great images from around London at a moment’s notice.’

Tour de France shots, taken by spectators, ended up in the London Evening Standard

Tour de France shots, taken by spectators, ended up in the London Evening Standard

So, is there a living to be made for the eagle-eyed? By 2014, Scoopshot, a free app that has been downloaded around 600,000 times, had paid out more than $1/2 million to amateur and professional users worldwide. An image of Venus passing in front of the sun was among the top earners, garnering $170 for the photographer.

There are not always rich pickings from a single image, but Scoopshot contributor Arto Mäkelä pulls in the bucks by submitting lots of them. Equipped with a DSLR and a smartphone, he has quickly racked up earnings of €20,000.

Mäkelä supplies event photos for news agencies – his largest payout for a single image being a €50 shot of a Finland hockey championship.

Scoopshot takes up to 30 per cent commission – less if the photo is for a ‘task’ set by the buyer.

The real cash flooded in for Mäkelä when a directory service company created a task, challenging Scoopshot users to photograph every company in Finland, paying €1.50 for each one.

‘I just started biking and driving around, taking pictures and enjoying the view,’ says Mäkelä.

Danger zones

Money aside, there are obvious dangers in putting yourself in the eye of the breaking news storm.

It’s a dangerous profession. According to the International Federation of Journalists, 118 journalists and media staff were killed in 2014, and 17 more perished in natural disasters and accidents while on assignment.

Recent Hollywood crime thriller Nightcrawler tells the compelling fictional tale of amateur videographer Lou Bloom, who makes a living by selling gruesome video footage of night-time car crashes and crime scenes to TV news channels in Los Angeles.

He races to be first on the scene. His earnest assistant – who is killed by a gunman – becomes part of the visual story.

Amateurs chase gruesome stories in the film Nightcrawler [Photo credit: Chuck Zlotnick/ Distributor: One Road Films]

Hollywood hyperbole or a real-life threat? A prominent former Fleet Street photographer, who asked not be named, says: ‘Little consideration seems to be given to the danger some news situations may present to the unwary “citizen journalist”.

‘A lack of knowledge of the basic rules has seen some using their camera phones within the precincts of a Crown Court, the unfortunate hopefuls finding that instead of seeing their picture of some law-breaking miscreant “on the telly”, they’re invited to sample the inside of a prison cell, minus their camera phone.’

Notwithstanding publication, taking people photos without permission can aggravate a sensitive subject, as AP readers know.

AP has anecdotal evidence of unrest in parts of Ilford, in north-east London, for example, where ‘authority figures’ have apparently cracked down on street photos.

Demotix, a photojournalism website that lists ‘ordinary people’ among its 30,000 contributors, admits that photojournalists of any level can be hurt or killed. Although not a belt-and-braces guide to safety, the site’s training page contains helpful links to other organisations’ websites, including www.newssafety.org.

User-generated discontent

The BBC invites budding citizen journalists to send in what is known in the trade as user-generated content.

However, the BBC does not generally pay for material. Its terms state that it will only pay for user-generated content ‘in exceptional circumstances for BBC News’.

Some professionals are fearful of a free pictures market, or of reporters equipped with iPhones replacing them, as seems to have happened at the Chicago Sun-Times, for example.

In the UK, Newsquest recently became the latest newspaper publisher to announce reductions in its quota of photographers, partly as a result of the increased use of pictures submitted from ‘external sources’, according to a report by the National Union of Journalists.

‘There is no question that the rise of citizen journalism has had a catastrophic effect on professional news photographers…’ says Nottingham-based photojournalist Pete Jenkins.

Can amateurs and professionals work side-by-side? Jenkins says: ‘If the question is, “Can the public reliably replace the quality, speed and professionalism of the dedicated professional?” then I suppose it could happen on rare occasions, but on a regular basis – you’re having a laugh, aren’t you?’

Broken news

As many news outlets trawl social media for ‘free’ material, traditional agencies have been badly hit, complains AP’s unnamed, now-retired Fleet Street source.

‘Many regional news agencies that relied on such commissions either no longer exist or have had to dramatically downsize, reducing the aspiring photographer’s career chances of getting in on the bottom rung of the profession.’

In pre-digital times, an amateur contributor would be paid ‘the going rate’, he explains.

‘Even if not used, newspaper picture desks – as a goodwill gesture – would invariably give an amateur a few rolls of film for their trouble. Sadly, such goodwill seemed to fly out of the window when new technology came knocking at the door.’

With technology enabling 500 million tweets and 70 million pictures to be posted on Instagram each day, potential breaking news is around every corner for the keen amateur.

Sometimes, you just have to be on the right corner, at the right time. And being armed with 21st-century technology helps, as our Bond video tweeter points out: ‘Last time this happened in a big way was when I accidentally got ushered into Downing Street through the main gates when Tony Blair was elected [in 1997]… I was just passing at the right time, and got some photos on film, but there was no way to share them like there is now.’

News websites

www.newsflare.com

www.newsvine.com

www.digitaljournal.com

www.allvoices.com

www.examiner.com

www.scoopshot.com

witness.theguardian.com

www.ireport.cnn.com/open-stories.jspa

www.en.wikinews.org

newsparticipation.com

www.bbc.co.uk/news/have_your_say

news.sky.com/story/706426/send-us-your-videos-and-photos

CASE STUDY: Citizen journalism goes viral

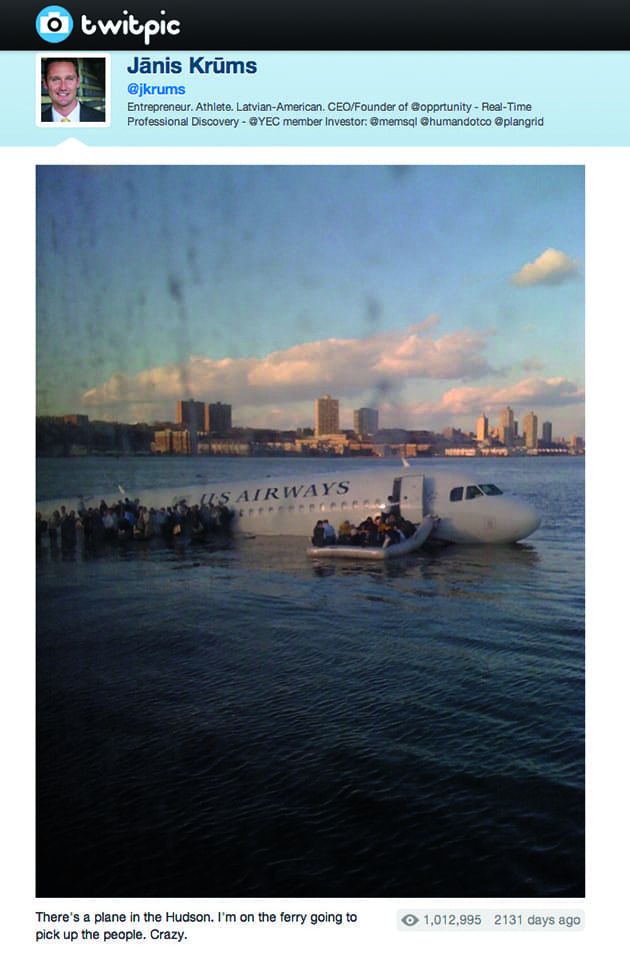

Janis Krums’ twitpic of a plane crash in New York sent news media wild

Unaware of the media frenzy he was about to trigger, on 15 January 2009, Janis Krums tweeted to his 170 followers: ‘There’s a plane in the Hudson. I’m on the ferry going to pick up the people. Crazy.’

Janis posted a camera phone image of the crashed plane on Twitpic, a picture that would become a defining moment in citizen reporting when the post went viral.

Handing his phone to a passenger, Janis went to help a flight attendant.

When he got it back Janis found himself speaking on live TV and besieged by news networks.

Speaking to AP, Janis says he did not get paid for the image initially, but as copyright holder, he made sure that he did a week later.

[Photo credit: Janis Krums]

Asked if he would do anything differently now, Krums says: ‘I would have done the same thing – I wasn’t there as a reporter. I just happened to be there and shared what I saw with my immediate followers. I had to quickly learn how to protect the image and, unfortunately, that process has not gotten any better for someone sharing breaking news today.’

Krums now has more than 10,000 followers on Twitter.

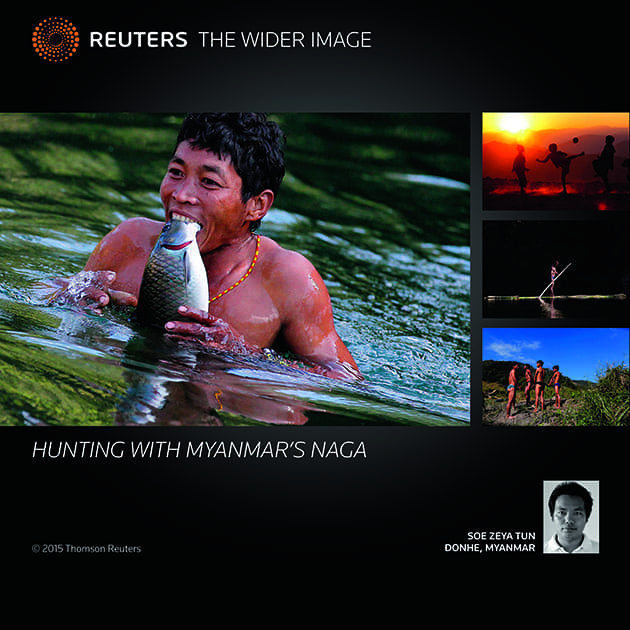

CASE STUDY: News agency Reuters targets ‘wider image’

Russell Boyce is global editor for News Projects, Pictures at news agency Reuters. He does not see citizen journalists as a threat, but rather as another resource in the visual story-telling process.

However, Boyce asserts that images published on social media can be a ‘free-for-all that lacks journalistic integrity’.

Asked to elaborate, he says: ‘Social media has given everyone a voice and it is a powerful tool for freedom of speech. It gives people a platform to say whatever they want to anyone who will click to read, watch, look or listen.

‘At the same time, it allows people to hide behind anonymity. This anonymity is a double-edged sword. On the one side, it protects those who may be punished for revealing the truth when those in authority don’t want the truth to be known.

‘On the other, it protects those who spread lies from being accountable. Journalistic integrity, and I include news pictures, is about unbiased reporting, accountability and reputation.’

Reuters has a global network of photographers – both staff and contract – alongside occasional and regular stringers.

Among those covering breaking news is photographer Jason Reed, who was on the ground to document the coffee shop hostage scene in Sydney, Australia, last December.

However, Russell Boyce is now exploring ways for photographers to tell more in-depth stories through their pictures, in a project called the Wider Image.

Reuters is pursuing ways to tell more ‘in-depth’ stories through photographs [Photo credit: Thomson Reuters]

‘In modern news gathering, the breaking news picture is only one important element of the story and is often only a starting point to tell a story visually,’ Boyce asserts.

‘What sophisticated news consumers want to see is pictures to help them understand what is happening in the world around them, so they can form educated opinions.’

He adds: ‘The challenge professional photojournalists face is to ensure they are shooting pictures that have a value beyond what has already been seen.

‘This gives a certain amount of creative freedom to those who have the ability to develop visual skills and shoot powerful pictures, especially with the amazing photographic technology available today.’

Over the past year, Reuters has carried out face-to-face educational workshops with photographers worldwide about the Wider Image project. The best photos are showcased on the agency’s Wider Image app.

As of early January, the app contained almost 300 photographer profiles, and photographers were already ‘pitching great story ideas’.

Boyce expects every photographer to become involved: ‘They are, of course, always focused on breaking news first and foremost,’ he says.

Avoiding mistakes

Faced with a deluge of social media posts, analysts and editors must judge if images are what they purport to be. The location, date and time that a photo was captured are among the factors that must be verified, plus the reliability of the source, to ensure the image is neither a hoax, nor presented out of context, even if, in technical terms, it may be a genuine photo.

Reuters’ Russell Boyce explains how a photo of Osama Bin Laden’s body circulated online after his death in 2011.

But Reuters editors spotted inconsistencies in the apparently bloodied face of the former al-Qaeda leader. The most glaring was that the lower part of the face had been lifted from a 1998 image of Bin Laden at a press conference.

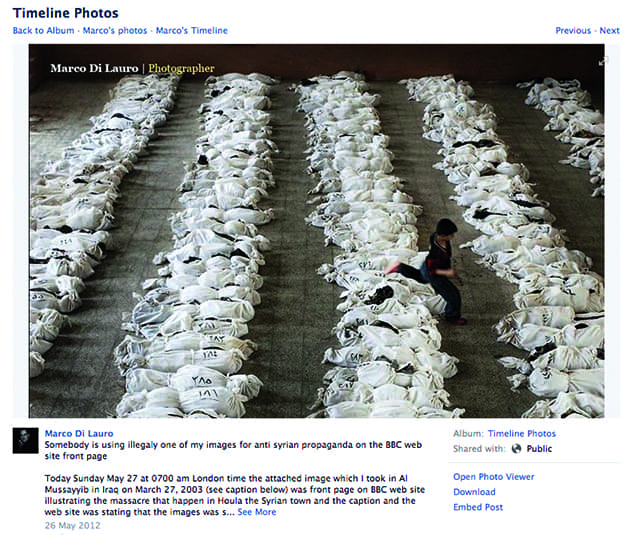

Mistakes happen, though, as highlighted by Claire Wardle, an expert on user-generated content. Speaking at a social media workshop for journalists, held at The Guardian’s offices last year, she told how, in 2012, the BBC mistakenly published a photo, spotted on Twitter, that purported to show the aftermath of the massacre of 100 people in Houla, Syria.

It turned out to have been taken almost ten years earlier, in Iraq – and was captured by professional photographer Marco Di Lauro (below).

How to spot a fake photo

A simple search on Google Images can determine whether an image has been published previously, for example. Another free tool is TinEye, which allows users to upload an image and conduct a ‘reverse image search’.

Google Street View and satellite data on Google Earth can help corroborate the location suggested in the image, using identifiable landmarks such as church spires and trees. A quick check of local weather information, using the website WolframAlpha, can also help establish whether the conditions tie in with those at the date and time suggested by the person who posted the online photograph or video.