In 1973, Magnum photographer David Hurn established the now world-famous Documentary Photography course in Newport. Now running at the University of South Wales (USW) in Cardiff, this year it celebrates an amazing 50 years since its inception.

Knowing just how many well-respected alumni it had, not to mention the luminaries who had taught on it over the years, an anniversary piece seemed like an obvious idea. I had little clue that it would end up spanning more than 20 different interviews with a broad range of people – and I could have gone on to interview dozens, if not hundreds more.

Such is the influence of this course, that every time you speak to someone, they insist that you really ought to get in contact with this person, or that person. I’ve no doubt that an entire book could be written on the impact this school has had on British (and even global) documentary photography.

Since its inception in 1973, the list of names who taught on the course, either regularly or as guest speakers, includes (but is certainly not limited to) David Hurn, Daniel Meadows, Ken Grant, Paul Reas, Martin Parr, Josef Koudelka, Clive Landen, Ian Walker, Ron McCormack, Celia Jackson, Lisa Barnard, Sir Tom Hopkinson, Don McCullin, Keith Arnatt, John Charity, Barry Lewis, Bll Jay, Roger Hutchins, Patrick Sutherland, Paul Graham, David Barnes, Peter Fraser, Paul Seawright, Jon Benton Harris and far more besides.

Meanwhile, the alumni list is just as illustrious. It includes (but again is not limited to), Simon Norfolk, Ivor Prickett, Anastasia Taylor-Lind, Paul Lowe, Sebastian Bruno, Clementine Schneidermann, Tish Murtha, Lua Ribera, Sue Packer, Jack Latham, Tom Jenkins, Linda Whittam, Guy Martin and more. Graduates from the school – which now covers BA, MA and PhD level – work across the globe for top news agencies, galleries, newspapers, magazines, and other leading institutions.

For this piece, I spoke to an extraordinary amount of different people – many of whom from the lists above. The over-reaching message seemed to be that this was, and is, a life-changing course that has altered the face of documentary photography in ways that many will have no realisation thereof. Many spoke of the lifelong friendships and support fostered by it, as well as the intensity – especially in the early years – of the work involved.

The beginnings were quite humble. David Hurn, who is Welsh but had been living in London and enjoying a very successful career as a photographer, decided to move back to his homeland in the early 1970s, looking for a more peaceful life. On arriving back, he was approached by various important figures in the Arts Council and local art college with a view to setting up a new photographic course. Remembering that this kind of education was very much in its infancy at the time, David took the view that he would be willing to do it with a few caveats – that he would have control over what was being taught, who was let onto the course and, most importantly, that the aim of the course was to get people into paid employment.

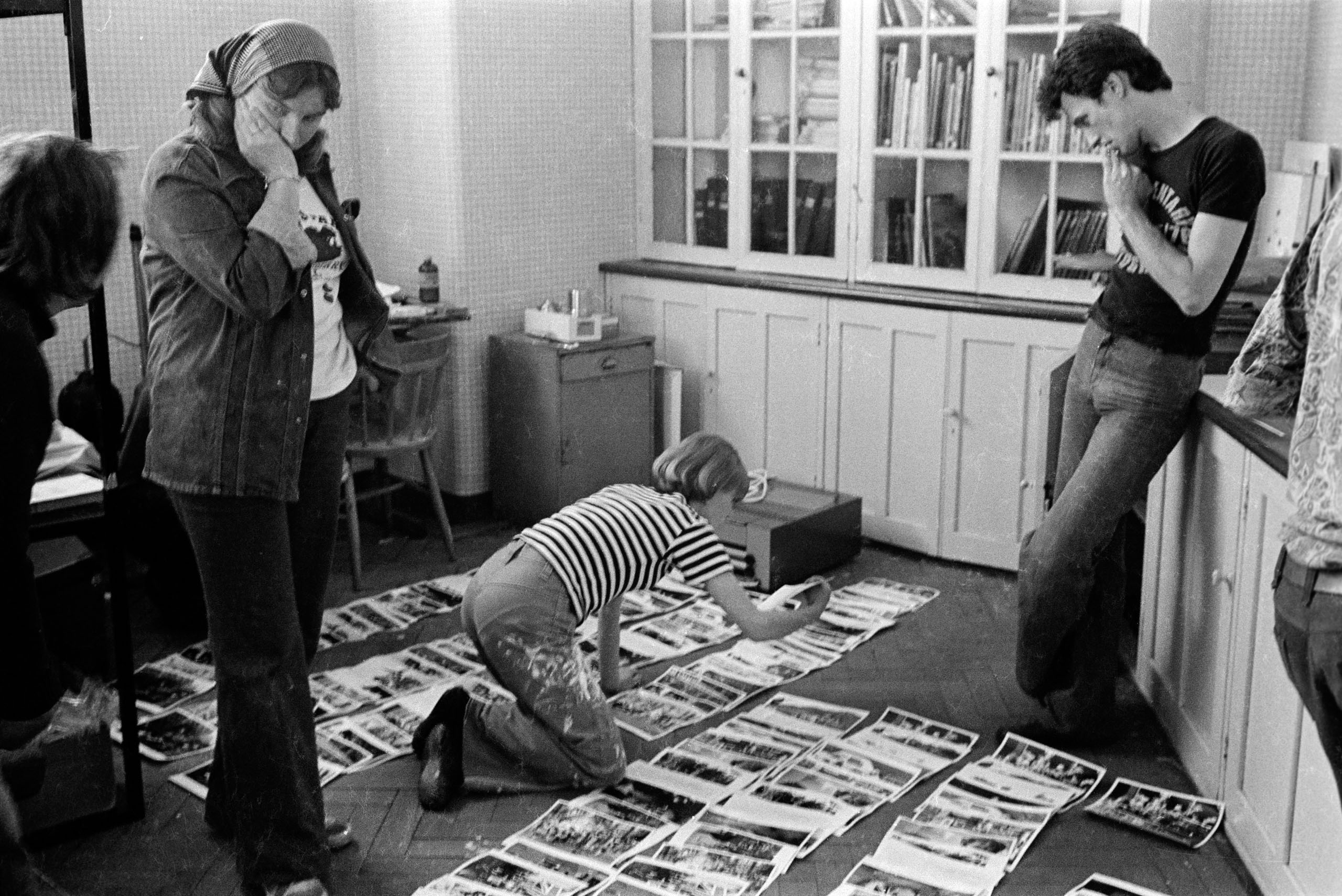

Newport, 1977. Documentary Photography students covered the Queens Jubilee. Students went all over UK and got their film back to Newport where others processed and printed them © John Charity

After discussing his ideas with his friends Sir Tom Hopkinson, once the editor of the Picture Post, and Don McCullin, of course the notorious war photographer, he was pretty much ready to go. He describes the setting up of the course in an arts college, in a blank space that was yet to be built, two enormous bits of luck. The first meaning that there was no real government supervision or insistence on what should be taught, and the second meaning that he could set up the facilities in a precise way.

Publicity

Having a huge amount of contacts in Fleet Street, David was able to generate publicity for his new course – he believes Amateur Photographer even covered it too. In the first year – 1973 – the course lasted just a year and was designated as a TOPS course (Training Opportunity), meaning that the typical students it attracted were extremely diverse – many of which had been made redundant from the local industries of steel and coal in the area. In fact, the course was overwhelmed with applications, such would prove to be the case for many years to come as its reputation grew. David didn’t choose people to join based on existing work though. He says, “I deliberately didn’t look at portfolios – I knew that steel workers and miners aren’t going to have those. They didn’t even necessarily know they wanted to be photographers. I just wanted to talk to them about ideas they had about life. It worked on the theory that teaching somebody to get pictures in focus – that’s easy. What you can’t do is persuade people to be interested in things.”

And why documentary photography in particular – not something more general, or geared towards another subject? “We called it documentary because I felt that the sensible public have a rough idea what that means. We were not going to do anything commercial or fashion – that relies enormously on how good the models are, which I knew about having worked for Harper’s Bazaar. The idea of teaching a fashion course in Newport was to me nonsensical – you didn’t get models walking down the high street there.”

David was strict, but fair, with his students – bearing in mind at the beginning he was the only teacher. “I decided everything would be done as professional photographers do it. I locked the door at 9am, if the student wasn’t there then they just didn’t get in. The idea being that if you are even one minute late for a deadline, you don’t get published. Within a week, everybody loved it.”

The course covered the great photographers – some of whom would come and visit David, and therefore the students – as well as practical elements of being a documentary photographer. This went far beyond the basics of operating a camera. David explains, “I would go to the local mosque and I would say to the imam, will you come and talk to us about how to behave should we come into the mosque – and I’d do the same for all the local religious centres and so on. I would also bring in people from other industries – like poets and artists – and ask them how they make money.”

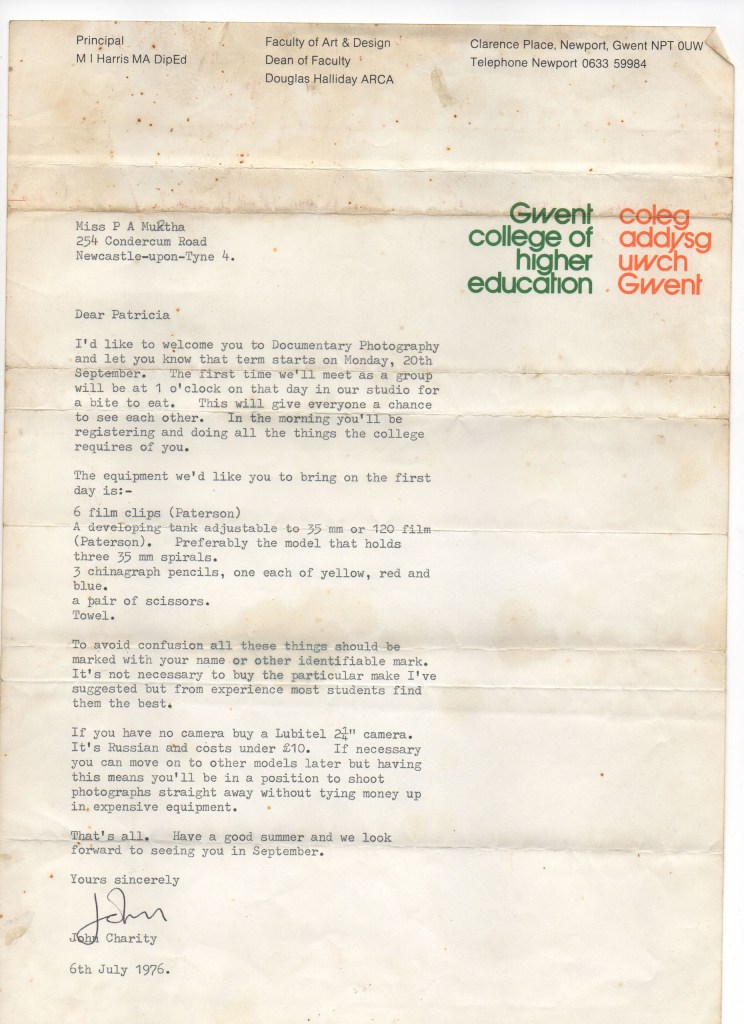

Tish Murtha’s acceptance letter, signed by John Charity, July 1976. © Tish Murtha / Ella Murtha

Almost straightaway, the course became incredibly successful and David was able to employ more staff. He always favoured teachers who were also out there making work themselves – like himself. Generally he found that students respected them more, and, with the advice they had being provably relevant. The course also expanded to two years, with the second year giving students the opportunity to engage with all the contacts David had built up in London on picture desks, particularly the colour supplements which were still in their golden heyday at the time.

David left the course in the late 80s, not being happy with it turning towards becoming a full undergraduate degree, and therefore losing some of the original ethos of accepting students from a wider range of life. But, the course and school today still includes David’s name as a testament to the legacy of what he created.

“The bees knees”

Daniel Meadows came to the school in 1983, having previously taught at Humberside College after making a name for himself for his Free Photographic Omnibus project in 1973. By that time, ten years into the course’s existence, its reputation was significant. “It was the bees knees as far I was concerned,” Daniel says. “It was the only course I’d really wanted to work on. I was kind of serving my apprenticeship at Hull because I’d been practicing as a photographer for a decade or more, but I had a family and suddenly the world of freelance wasn’t quite so suitable. But being able to teach, while also maintain some practice was a good option at the time.

“The course was the only one called documentary photography then, and that’s my subject. Everywhere else wanted you to be a graphic designer or an artist, but I believe that documentary has its own set of rules and way of behaving. I also respected David Hurn, as well as Ron McCormack and Clive Landen who were all teaching there when I joined. It was like landing in the place of desire.”

Firmly believing he was there during the course’s “golden years” (he left in 1994), which he attributes to its simple ethos and diverse range of applicants. “It was a magical course, I’ve never since or come anywhere near to the kind of quality teaching and learning experiences – it was very special. We had teenagers off Youth Opportunities Schemes, middle-aged men who’d been made redundant two or three times following Thatcherism, graduates from ‘posh’ universities – all mixing in the same darkroom. And the simple structure – everybody did the same briefs, “man at work,” relationship, establishing shot, portrait, three picture story, five picture story, big picture story. I never taught a course that was as well thought out and delivered in the same way that David’s did.”

Despite the fact that several “big names” in documentary photography did the course while Daniel was there, it’s not those who he holds the most fondness for. “For me the most satisfying teaching was when people had a genuine revelation about how photography was going to change the way they lived. There was a woman there who had a child with severe learning difficulties who wanted to tell the story of what respite care means to parents – she did it from the inside out. I love it when people make pictures about something they really know and in that process of teaching them how to do make better pictures, you learn a subject too.”

Daniel fought for some time to keep the course as it was, but ended up also leaving dissatisfied with the change to the course being a three-year undergraduate degree. He also believes that it moving to Cardiff has been a huge shame for the city of Newport. “If ever a town needed an art school, it’s Newport. Things like this are enriching, and we built a community around these students who got involved with things like The Newport Survey, which was published every year.” Several people have mentioned the survey to me during my research for this piece. In essence, it was put together with the help of the graphic design students, covering a different topic every year, such as religion, rivers, neighbours, family and so on. The results would not only be published in a real book that could be bought, but also exhibited at the nearby museum and art gallery.

The Newport name itself indeed became synonymous with excellence, as Daniel recalls, “David often refers to a meeting he had, I think with The Sunday Times or Magnum, and somebody said, “you’re the one that started at Newport Mafia!” – you had art directors and picture editors all talking about the Newport Mafia.”

A changing industry

Ken Grant, whose name readers might recognise for his recent AP-award winning Chris Killip show at The Photographers Gallery, which he co-curated with Tracy Marshall-Grant, taught on the course for over 15 years, having first joined in 1997. He later went on to become the course leader in 2008-9, not long after he believes the wider photographic industry had changed dramatically.

“In 2004, with the Tate doing its first big photography show, different types of things were happening. People were working with the book in a much more elaborate way, digital practices were coming in – people were starting to think we don’t just do a beginning, middle and end narrative anymore – you couldn’t get to the frontline anymore and you had to think in a much more oblique way about how you worked.”

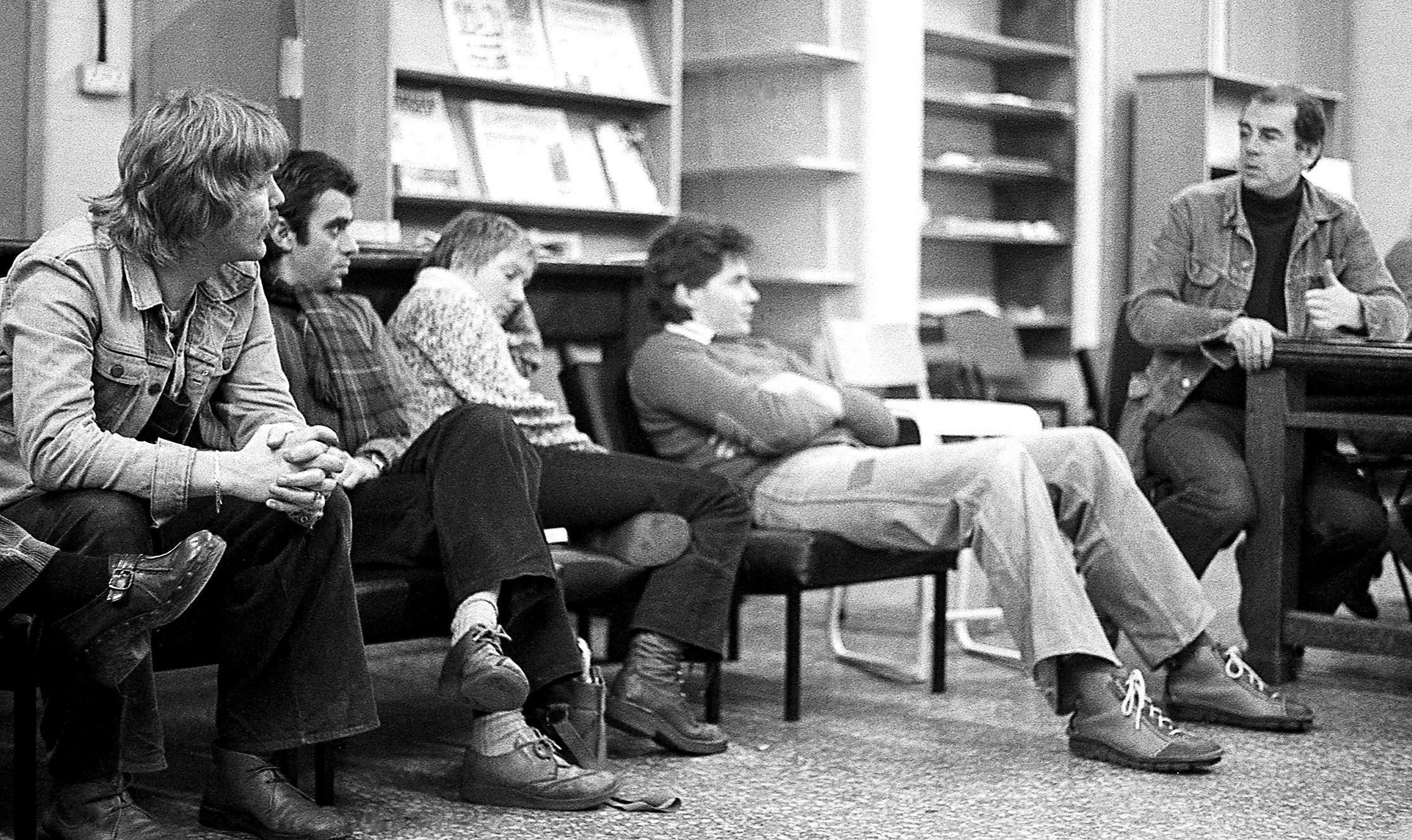

David Hurn teaching students – the photograph is by student Tish Murtha. © Tish Murtha / Ella Murtha

Although based in South Wales, one of the best things about the Newport, and now Cardiff, course has always been how much of an international focus it has had. “You could imagine something that’s really quite local in Newport, but we’d have people coming from far and wide,” says Ken. “An upshot of that is that people wouldn’t disappear at 5pm – the course was their home in many ways, and they really wanted to be there – they’d already experienced other things in their lives, but they were hungry for it and they’d come from different places because of that.”

Paul Cabuts taught on the course having previously been a student himself of the BA as a mature student in 1993 and later spent a lot of time researching the development of the course for his PhD from the European Centre for Photographic Research. Later, he would go on to become the academic subject leader for art and photography, overseeing all of the photographic courses.

In the mid 2010s, Newport merged with the then University of Glamorgan to become the University of South Wales. Glamorgan already had a photojournalism course, so Paul says it was potentially a dangerous time for the Documentary course, being so similar. “It was quite a good course, but it was only two or three years old – I worked quite hard to make sure the Documentary course stayed, purely because of its fantastic legacy. Myself, Paul Reas and Ken Grant and others, we all made a very firm case for why documentary photography had to maintain its place as a leading course. Luckily enough, that did happen.”

“A sort of aura”

Paul is another who believes it was a shame for Newport, the city, that the course eventually moved to Cardiff. “Everybody associated Newport with documentary photography – but students do generally prefer to be in Cardiff than Newport, for obvious reasons. But, Newport did have this sort of aura around it. The people of the town had a really strong bond with the students, which was evidenced by the annual Newport Survey, which happened for about 10 years and made the relationship between the students and the town really something quite important.”

In 2015, Paul left to work at Falmouth Photography, which also has a very well-respected photography course – which he says followed the same kind of tried and tested structure that Newport had set up all those years before, again demonstrating the impact that it had had on the wider photographic and educational world.

Paul Reas is a name which I felt like I heard several hundred times across the many interviews I did for this piece, so naturally I had to meet the man himself. His time with the course spans almost its entire duration, having first been a student himself in the early 80s, then later a technician and latterly a teacher on it until he retired just a couple of years ago.

He was a mature student when he joined, having had a previous life as a bricklayer. Like many, he says the course changed his life – making him middle class. “For me, it was the first time I’d been around people with different life experiences – people who had done other things with their lives. It forced you to re-examine all your preconceived ideas about people and people’s backgrounds, such as class and identity.”

From the course he says he took away something extremely meaningful that goes beyond skills as a photographer. “It gave me a realisation of my responsibility to represent things as truly, fairly and honestly as I could. To be compassionate and give something about – it’s not all about what you take from communities, but what you can contribute too.”

Having spanned such a broad stretch of time, Paul’s been able to observe big changes. “The professional world has changed so much. When I studied, it was still possible to make a really good living from working for magazines and newspapers – now people have much more diverse careers and the course had had to change to reflect that. Now we might look at commercial opportunities, or the art world, a lot more, for example.”

Moving to the present day, I also spoke to current BA Course leader David Barnes, MA course leader Lisa Barnard, plus lecturers Karin Bareman and Professor Mark Durden.

David, as with Paul Cabuts and Paul Rees, is himself a former student – such is clearly the draw of the course. He believes that the current BA runs on the same ethos of David Hurn’s original intentions from 1973. “We’re completely open minded about who comes on the course – so we have people who have done full careers and a really broad range of ages, so we still get that melting pot of people.” The course also keeps numbers small – just like the old days too, but it has expanded with the industry too. “We’ve been able to bring in all dimensions of documentary, including critical thinking about representations and ethics. While the industry is sometimes seen by some as contracting, it’s actually the opposite – it’s expanded, just in different directions.”

Storytellers

At the university, there is also a BA Photography course, but David feels it’s important that the Documentary course continues to exist in its own right too. “Why we teach specifically documentary is because at its course, it’s an interest in storytelling. Our students all want to be storytellers. They’re all passionate about something in the world.”

Although it has moved to Cardiff, he still also believes that the location brings something special too. “South Wales is a great place to go out and shoot pictures because people are really friendly, and kind of nosey in a nice way. Of course, people are travelling and going way beyond Wales at the end of the course, but in the first instance you’ve got to learn the ropes here and I think that works really well.”

By contrast, the MA Documentary Photography is run completely online, in order to attract a more global audience who don’t have to move from wherever they currently are in order to study – it also attracts lots of mature students. “The photo scene is very specific in the UK – it’s quite traditional,” says Lisa Barnard. “Whereas in Europe, documentary is treated completely differently. By broadening this out to be global, I get students that are interested in very long term projects, and they also use other tools beyond the camera to talk about their ideas too.”

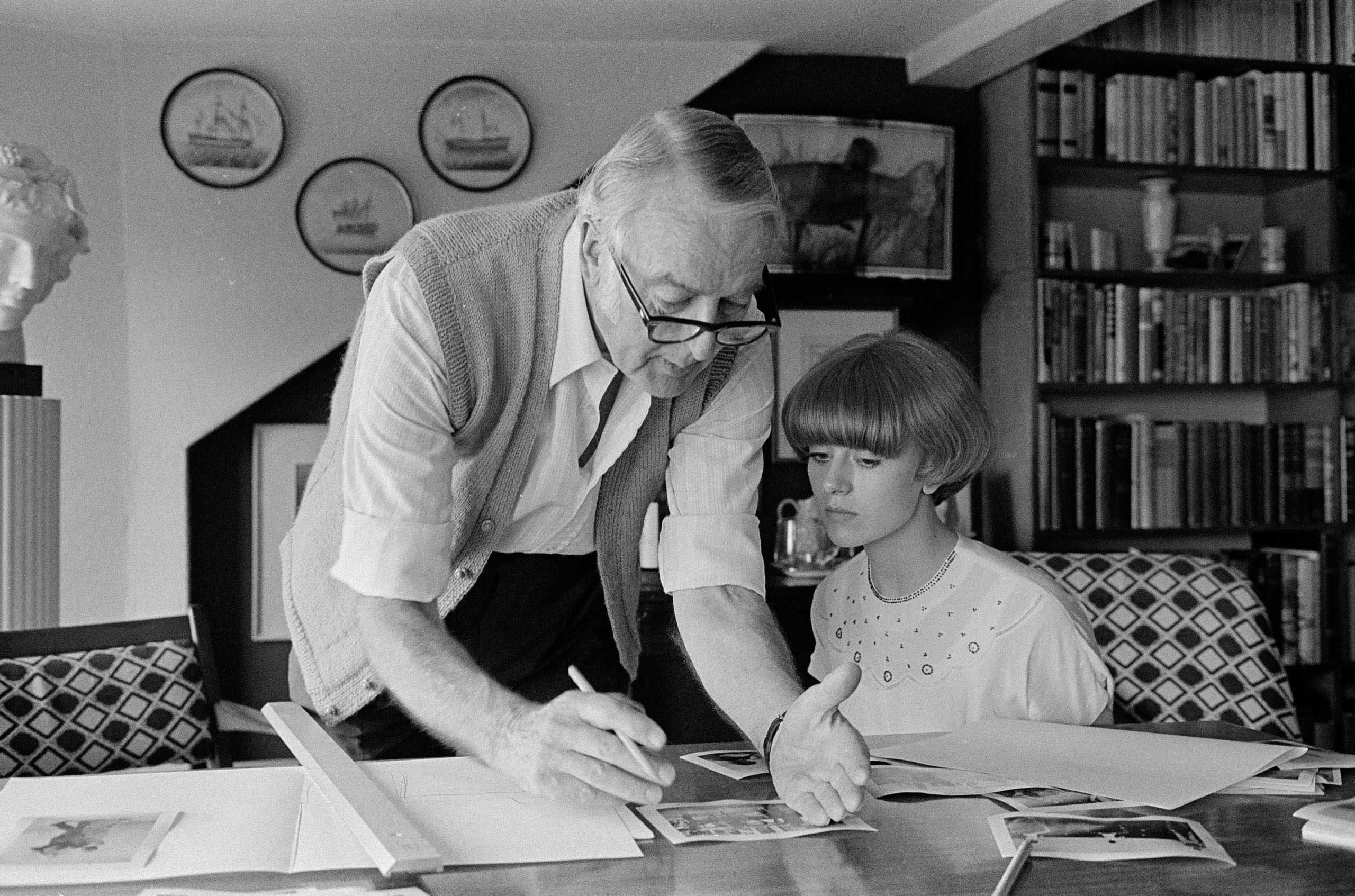

Sue Packer (then a student) taking advantage of Tom Hopkinson’s (later Sir Tom) permanent offer to help students with layout if they came to his house in Penarth. 1977. © David Hurn

Interestingly, Lisa says the opposite to David Barnes, in that the MA is not actively trying to maintain the legacy of David Hurn. “It’s not to say I don’t respect his approach, but on our MA it couldn’t be further apart. I think in a decolonialised world that we live in, there’s a responsibility as image makers. I fundamentally believe that people that are making work should be making work in the countries that they inhabit – which is why I started running the programme online. That’s completely different from the historic idea of the white man who travels the world to exploit it for images. It’s very different.”

Mark Durden has been with the school since 2007, and works across the BA, MA and also supervises PhD student – USW is rare in that it runs courses in documentary photography across these three levels. While he appreciates and recognises the schools deserved reputation, he says its important not to become fixated with that past. “Since I joined, the approach to documentary has expanded and become more encompassing – historically it tended to be a bit narrow, both aesthetically and conceptually. In the past, it was rather unthinking and anti-theory, whereas now students have a very healthy relationship to critical theory.”

One of the most recent recruits to the school is Karin Bareman, who has been teaching there for less than a year. Unlike many of her colleagues, she’s not a practicing photographer, but, she has extensive experience in curation, which helps to bring another element to the students. She came to the course after conducting some guest lectures where she found the students to be hugely engaged, something she had not necessarily found elsewhere – “they were the most enthusiastic, the most prepared, the most engaged – the students are a real pleasure to work with,” she says.

She’s also keen to point out the supportive atmosphere, which is helped by keeping course numbers low. “You actually get to know each other very quickly – and the students also learn a lot from each other and support each other very strongly.”

It’s clear that an awful lot has changed since 1973. But it’s also very clear that the legacy of David Hurn’s original course is still very much going strong, and over the last half a century has had a phenomenal impact on documentary photography. It became quite clear to me while researching this piece that I could have spoken to many hundreds of people who have some connection to Newport/Cardiff, and I was delighted to discover that there is indeed a book in the works from Paul Cabuts which will look at some of the course’s aspects and impact on the wider photographic world. For now, I leave my research here – but I can’t wait to find out more in the future.

To find out more about the current courses, visit southwales.ac.uk. Keep reading for more from Newport / USW alumni, who each tell us what it was like to study on the course.

Anastasia Taylor Lind

Anastasia completed the BA Documentary Photography in 2004 and has worked for National Geographic, TIME, Vanity Fair, The New York Times, The Guardian, The Sunday Times and more. She is also a 2018 Harvard Nieman Fellow and has won numerous awards for her documentary and war photography, and is currently working in Ukraine.

A man weeps beside a bloodied stretcher outside the emergency department of the Republican Medical Centre in Stepanakert, November 2020 © Anastasia Taylor-Lind

She recalls being taught by Clive Landen and Ken Grant, the latter of which she says, “never stopped being my teacher” – a testament to the kind of connections made at Newport. “I wanted to be a photojournalist and go and do it as soon as possible. I asked my A Level teacher where I could learn how to take pictures like Don McCullin and they said “At Newport”, so I applied and had the good fortune of being accepted.

“It taught me how to build a photo story using the building blocks which I believe David Hurn had coined. I got back from Ukraine recently and I’m still going out and making those kind of pictures nearly 20 years later.”

Paul Lowe

Award-winning photographer Paul Lowe is represented by the globally acclaimed agency VII Photo and has been published in various outlets including Time, Newsweek, Life, The Sunday Times, The Observer and many more. As well as being a photographer, previously he was the course leader on the MA Photojournalism and Documentary Photography at the London College of Communication and is now Professor of Conflict Peace and the Image at LCC. He studied at Newport from 1986 – 1988.

A young girl plays with a ball in the street alongside the River Miljacka in a ceasefire during the siege on Sarajevo by Serb troops, 1994 © Paul Lowe / Panos Pictures

“It was extraordinary because it was incredibly intense. I don’t know if it’s ever been replicated really in photographic education, as far as I know.

“I think if there’s a legacy of that course, funnily enough, I try to argue that the course we run at LCC is probably the closest to the spirit of that original course.

“I started it with Patrick Sutherland, who taught me at Newport and had set up a postgraduate diploma at LCC. He invited me to turn that into an MA in 2005 – and one of the interesting things about us is that you don’t need a first degree in anything if you’ve got some professional experience. Because of that, entry requirement or lack thereof, I think we inherited that quite consciously and built on it. We get a lot of people on our MA who are like the people that went to Newport when it was a two-year course.”

panos.co.uk/photographer/paul-lowe

Sebastian Bruno

Sebastian did both the BA and MA in Documentary Photography between 2012 and 2018. He has been exhibited, awarded and published numerous times since then. Originally from Argentina, he has stayed living in Newport since finishing the course, and often returns to USW as a lecturer.

Swffryd’s Thursday Lunch club, from the book The Dynamic, published in 2023 by IC Visual Lab © Sebastian Bruno

“One of the reasons we [he lives with Clementine Schneidermann – see further down] stayed so long after we finished studying and continue to make work here is because of the support we had from the course. I do quite a bit of teaching which I really enjoy because there is that act of reciprocity.”

Simon Norfolk

Often described as one of the leading documentary photographers of all time, Simon Norfolk completed the HND course at Newport in 1983, after completing an undergraduate degree in Philosophy and Sociology at Cambridge University. His work is held in major institutions around the world, he has won or been shortlisted for numerous prestigious awards including World Press Photo, Deutsche Borse and Prix Pictet.

Former teahouse in a park next to the Afghan Exhibition of Economic and Social Achievements in the Shah Shahid district of Kabul. Balloons were illegal under the Taliban, but now the ballonn-sellers are common on the streets of Kabul providing cheap treats for children. © Simon Norfolk

“The course was superb – a baptism of fire. I think I was one of the younger ones to do it, a lot of people had actually done stuff in life. They’d been a journalist, or a coal miner, or the Royal Marines or whatever.

“From the very beginning you were sort of thrown out the door – go out, shoot pictures, come back, process them, create a contact sheet, have a critique, back out the door again. The best thing really was you had to break down that social embarrassment about walking into a place.

“You were pushed very, very hard. They told us when we got there that they’d take one person too many so they were going to theow someone out at the end of the year. That meant our focus was amazing – you don’t get anything like that nowadays.

“The thing I walked away from that course is that storytelling is what matters. Yes, it must be beautiful – but it has to have a real spine through the work. I’m a political photographer who wants to change the world and that’s what I learned to do.

“To this day, the highest qualification I’ve got in photography is an HND – the same as my plumber. These days we don’t really have vocational degrees like that any more – which is a shame as that was the genius behind David’s course.”

Chris Chapman

Chris Chapman was invited to join the Newport course by David Hurn, where previously he had been studying Fine Art. Since 1975 he has lived and worked in Dartmoor, documenting aspects of local life. His photographs are held in some of the world’s most respected collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the International Center of Photography in New York. He has published numerous books and has been commissioned widely.

At the Llangibby Hunt, 1975 © Chris Chapman

He says, “I had bluffed my way into art college but couldn’t draw. When I discovered the camera, I used it as my sketchbook, working up large canvasses from my photographs. It never dawned on me I could just take photographs. David offered me a place on the course in 1974 and I never painted again!”

“It was a terrific atmosphere. David was a brilliant teacher and commanded huge respect. I remember a favourite phrase of his was ‘Go back and take it again!’ and of course we all did until the magic day arrived when he would look at your work and give praise.

“Without a doubt, the reason so many successful photographers come from that course is David’s skill both as a teacher and a mentor. I keep in touch with him still and was delighted to discover he had included one of my photographs in his first Swaps exhibition at the National Museum of Wales in 2017.”

Lúa Ribeira

Magnum photographer Lúa Ribeira completed the Documentary Photography BA in 2016, attending at the same time, and sharing a house, with some of the others mentioned in this piece including Clementine Schneidermann and Sebastian Bruno.

Untitled, from the series postnaturalism, taken

while at USW

© Lua Ribeira / Magnum Photos

Lúa switched from a different photography degree to join the documentary course as she felt it was closer to her approach. Her main teachers at the time were Paul Reas and Lisa Barnard, who she appreciated for their opposing views and willingness to share them. “The teachers were tough, that was important for me. What I learned stayed with me as I’ve worked over the last few years.”

She describes how Newport fostered a familial approach, and also believes that its location was a big help. “It’s a town you might not otherwise go to,” she explains. “And I feel that isolation in e area was very healthy because it created a kind of family feeling – everybody supporting each other, but with a healthy competitiveness as well. There was something really special here.”

Tish Murtha

Tish Murtha was one of the earliest students of the course, and although she died in 2013, she has become well-known in more recent years thanks to the work of her daughter, Ella. A documentary film directed by Paul Sng about Tish was released in November 2023.

Newport Tip, 1978 by Tish Murtha © Ella Murtha

Here, her daughter Ella describes her time in Newport.

“She started the course in September 1976 and graduated in 1978. I found the letter from John Charity welcoming her to ‘Documentary Photography’ in her stuff when she died, and it’s so lovely and informal. She was lucky enough to get an education grant from Newcastle City Council, which enabled her to go, but due to the sheer volume of film that they shot, she also worked in the evenings to afford it. She loved the place and the people and got a lot from the course. She worked incredibly hard, as she was desperate to learn the skills she needed to help make her a better photographer. I think Newport was probably very similar to Newcastle, so she felt very at home wandering around and meeting people along the way. The famous “man at work” project found her documenting Wilf a local scrap man – her dad was a scrap man, so she was used to exploring the tip looking for treasures. I remember her being very proud that the journalist Tom Hopkinson had come in to work with them and assigned them all a story to work on. She headed off to the ‘New Found Out’ pub in Pill for hers, and I really enjoyed looking through all those contact sheets. There were some right characters!

She just photographed what she knew, and that was people. She had always been a people watcher long before she ever picked up a camera, she knew she wanted to be a social documentary photographer, but she absorbed everything that David Hurn taught her until it became second nature. He taught her how to create a picture story and once this was ingrained in her, she returned to the northeast with great purpose and fond memories of Wales.

She met her good friend Daisy Hayes there, Daisy actually photographed my birth! Other friends I remember were David Swidenbank, Kevin O’Farrell, George Wilson, Clive Landen, and Sue Packer and a Swedish lad called Ingard. He is in a couple of photos from the time, but I don’t know his surname unfortunately, which is a shame as he had a lovely twinkle in his eye and I bet has some good stories.

It has been really special to connect with people off the doc photo course and hear their memories of the time and my mam. I visited her old student house in Colne Street, which is relatively unchanged, but couldn’t get into the tip as needed to book, and the pub was long gone, but it felt quite spiritual walking in her footsteps and imagining her at work. It was really good to speak to David Hurn and hear what it was like to teach my mam and how he swapped a print of Angela and Starky with her, as he thought it was so tender. I actually found myself in the exact spot it must have been taken because of the reflection of a building I recognised. It was a real goosebumps moment. I’m a very proud daughter.”

Clementine Schneidermann

Clementine Schneidermann studied for both an MA and PhD in Documentary Photography. She has won numerous prizes, including the Leica Oskar Barnack Newcomer Award and the Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize. She has been published in many outlets including The Guardian, The New Yorker and Creative Review. Originally from France, she has stayed living and working in Newport.

I called her Lisa Marie © Clementine Schneidermann

“The course was amazing. It was also discovering a new country at the same time. For the first year I commuted from Bristol, but in the second year I moved to Newport with Sebastian [Bruno], Lua [Ribeira] and others – we had a big house in Newport. It sounds cheesy, but I feel like it kind of changed my life.

“Because I’m not from Wales, we [she lives with Sebastian Bruno – see above] kind of felt like we finally had a family in the university – among the students and the lecturers too.

“Since we finished, the market has changed. It’s become much harder to make a living – even when we started people were telling us it would be difficult, but now it’s really hard. Now photographers are encouraged to tell their own stories and use their own voice – they’re starting to look inwards a little bit more.

“I appreciated the toughness of the lecturers when I was there. I did a project on burlesque dancers and thought I was Susan Meiseilas. I showed it to Paul Reas, who was very tough on it – I felt like crying. But, in the end, I was so glad he did because he really pushed me to work much harder.”

Jack Latham

Multi-award winning photographer Jack Latham has become well-known for his work surrounding conspiracy theories. He has published multiple books, been exhibited numerous times and also works as a lecturer at the University of West of England in Bristol. Originally from South Wales himself, he graduated from Newport in 2012.

Phantom Patriot was the name taken by Richard McCaslin of Carson City, Nevada, who, on January 19, 2002, attempted an attack on the Bohemian Grove after viewing Alex Jones’ documentary. He was imprisoned in California for 8 years. He now resides in Nevada and has a super hero base in his backyard which he refers to as the ‘Protectorate Outpost’ © Jack Latham

“I went to Newport because it was Newport. I didn’t have much of a portfolio, but I showed that I was incredibly passionate. I was offered a place by Clive Landen who said ‘I’m going to give you a place but if you f*** up, I’m going to kick you out personally. That has kind of followed me my entire career. I’m from Cardiff but I was never academically bright, and art wasn’t necessarily afforded to me growing up. The idea that I could even go to university was a huge thing.

“We always used to say you had support from Clive, you’d have brutality from Paul [Reas] and poetry from Ken [Grant]. But one of the best pieces of advice I received was actually from one of the technicians, who said, you shouldn’t finish university with a completed project.

“I’m proud to have gone to Newport. Coming from South Wales, the fact that it was in Newport is mind-blowing. I don’t think culturally people really gave a Newport a fair chance – it’s amazing it was documented for all those years using photography. It’s got a legacy and it will have always been an important place for British photography.”

Glenn Edwards

Photojournalist Glenn Edwards attended the course in 1983. He has worked for a wide-range of clients and is a former UK Press Photographer of the Year.

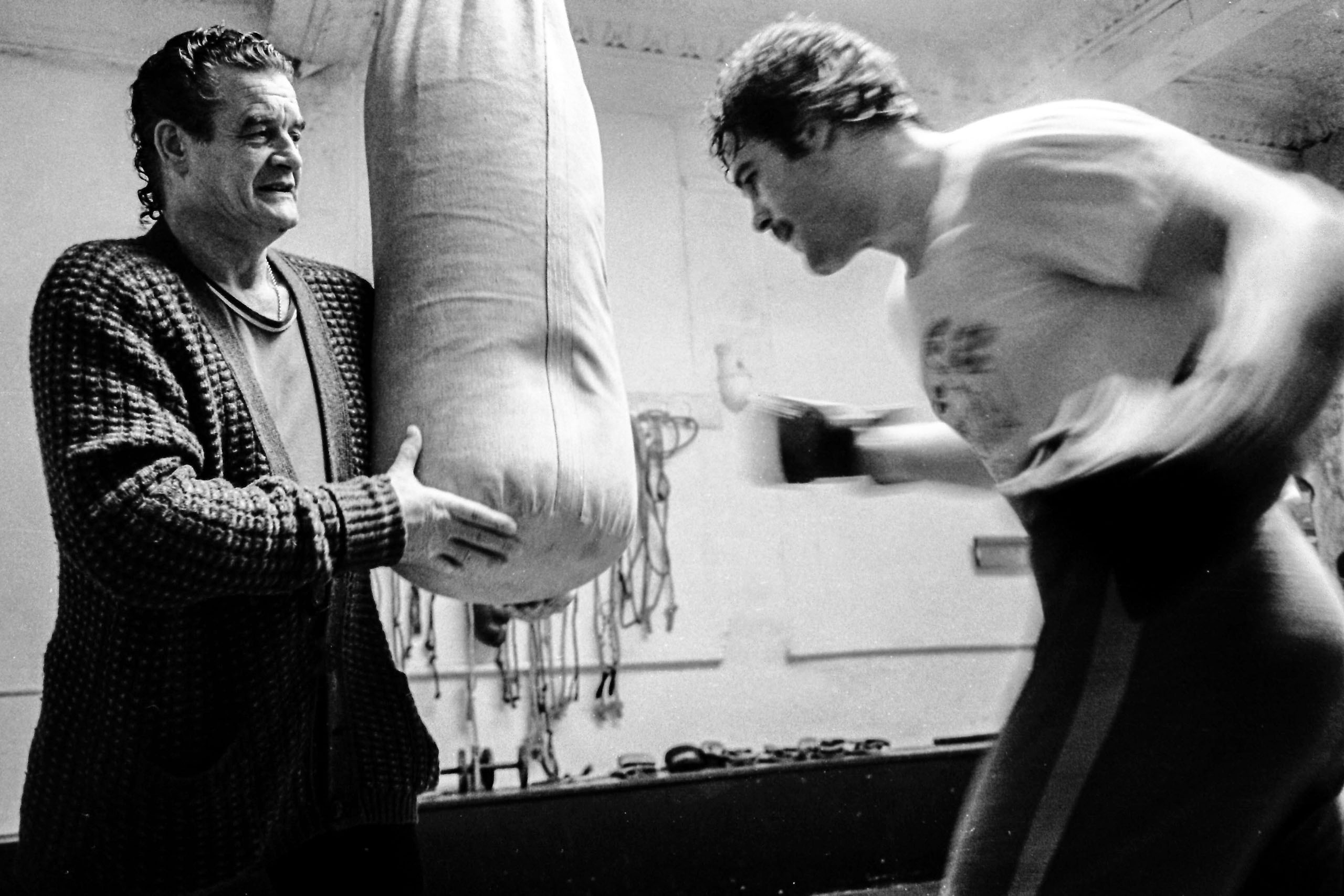

From the book and exhibition Yuckers Year. David Pearce training with his father Wally at the Waterloo Hotel in Newport before his British Heavyweight Title fight with Neville Meade in Cardiff September 1983. Not an environment you would find Fury or Anthony Joshua in the modern era. The first magazine to run a spread on this work was Amateur Photographer in 1983. © Glenn Edwards

“Without sounding over-the-top, the course was absolutely life-changing. I was in the steel industry previously, and I was extremely lucky to get in. I think there were about 350-400 applicants and only 15 of us on the course.

“It was totally practical. It was all about going out, making mistakes, and then going out again and again until you got it right. We were all a little bit in awe of David, but he is one of the most approachable guys you could ever wish to meet.

“From the get-go, we had to go out and find people to photograph. Forget the photography aspect, the social skills were equally important. It was structured in such a way to make you a working photographer – at the end of the day, what’s the point unless you can earn a living?

“Recently I’ve had an exhibition and a book of pictures that I took at Newport. We had to find our own stories and I discovered a local boxer – David Pierce, who went on to fight for the British heavyweight title. I followed him for a year and it’s recently been the 40th anniversary.

“It’s sort of come full circle, and that’s what Newport gave to me – knowing how important photography can be.”

glennedwardsphotojournalist.co.uk

Sian Trenberth

One of the youngest students to attend the course, Sian joined at age 18 straight from school in the early 1980s. Today she specialises in studio, portraiture and performing arts photography – but owes a lot of her craft to what she learned at Newport.

© Sian Trenberth

“I’d always loved photography, and I had a job at a theatre when I was at school as a dresser – somebody said there’s a photographer at the front of the house, you should go and speak to them. It happened to be David Hurn – I didn’t know who he was of course. I told him I was interested in the backstage stories, and he told me to join the course.

“I found it very hard, it was absolutely brilliant training and what I learned is still with me every day – it was a real hothouse environment. Standards were very, very high – David always instilled the being the best you can be type of approach. I don’t think that ever goes away. I’m a portrait and performing arts photographer now, but I adopt the “Newport approach” still.”

Iga Koncka

Iga is a very recent graduate from the Documentary Course at USW, where she was studied from 2018 until 2021.

© Iga Koncka

Studying in the midst of the Covid pandemic was a challenge for Iga, who came to the UK after completing her A Levels in Poland. She says “I loved being on the course. It shaped my work ethic and I learned so much about photography and the arts in general. I was only 18 when I emigrated and the course was a great anchor to the realities of a new country.”

As is more common with newer students, Iga used other forms as part of her studies, including short films, performance and installation. She says, “The majority of my course was during Covid, so we had to be very creative with the projects we produced, as traditional human contact was not an option. This limitation allowed me to explore my Polish identity more and think outside the box when photographing close surroundings and domestic spaces.”

Iga admits that she didn’t know of the course’s famous reputation until after she arrived, but is now proud to be part of its community. She finished the course with First Class honours and went on to study for an MA in Contemporary Photography at Central Saint Martins, where she was selected as this year’s New Contemporaries artist.

Curtis Hughes

Curtis Hughes is a very recent graduate of the USW course, having studied for the BA from 2019-2022, but he has already found a good degree of success, with some of his project ‘Modern Love’ being featured in the book ‘Love Story’ by Hoxton Mini Press.

Vero and Julius, from ‘Modern Love’ © Curtis Hughes

“My decision to pursue a photography course was prompted by a moment of epiphany while I was living in Guatemala and working on my first documentary project. I naturally gravitated toward the documentary genre, with a deep-seated fascination for people and their stories. It was my sister who recommended the course after I shared my aspirations of attending university to study photography, specifically documentary,” he explains.

After leaving school, Curtis had been working in customer focused roles, before leaving the UK in his early 20s to take in part in what had intended to be a brief gap year. Six years later he was still away, teaching English at schools in India and later Guatemala, and developing a love for photography, particularly portraiture.

On returning to the UK to study at the famous documentary course, he found it to be an “exceptional experience.” He loved the sense of community, the connections formed, both with fellow students and teaching staff – he says “they have become like family to me.”

His project, Modern Love was created during the final year of the course. “I embarked on a train journey across Europe, capturing couples in their homes who had met online. Throughout the entire process of making the work, I received unwavering support from my colleagues and lecturers, who encouraged me to question not only what I was doing and how I was doing it, but most importantly, why I was doing it. I believe that this process of feedback and collaboration played a significant role in the project’s success. To this day, I seek collaboration and feedback in my work, cherishing the lessons I learned during my time at USW.

Robin Chaddah-Duke

Robin graduated from the BA course in 2023, with the first two years of the course completely disrupted by Covid. He says, “Despite this, the course stayed active and the staff worked endlessly to make sure we were getting the education we had been promised. The skills I learned in these two rocky years meant that I was still able to produce a body of work I’m proud of.

An image by Robin Chaddah Duke

“I studied photography at my college where I was able to discover my interests more specifically which lay in documentary practice. I was recommended to the course by my tutor Tom Keating and was amazed by the opportunity to study under a course who had produced names whom I very much admired.

“I was only 18 when I joined, so I had a lot to learn about life in general and I think the course allowed me to do this in a way that is really special. What I valued most was the ability to explore my own interests completely freely. I was welcomed into various communities with open arms and introduced to so many different people from different walks of life. The mentality of using a camera to get to know people I would never meet usually is something they really push on the course.

“It feels quite surreal now that I think about it that I was on such a famous course. It has put out some of photography’s biggest names, and I guess I’m now next to them – right at the bottom of the plaque. Seriously, it feels great – I’m very grateful to all of the staff and my class for everything.”

Laurie Broughton

Laurie graduated from USW in 2022.

Baby on the table © Laurie Broughton

“I wanted to study documentary photography at USW because of its prestigious reputation for producing world-renowned photographers. The course’s alumni really impressed me and gave me confidence that I would learn the skills to make that step to being a freelance photographer.

“Being all consumed by photography has left a lasting impact on myself. It has given me confidence but a burning desire to constantly think about the next image that I would want to make.

“Having studied here I’ve been able to connect with other photographers that have been in my shoes. I feel very fortunate to have been part of this course as it has changed my life for the best.”

What is documentary photography?

I asked several of the interviewees here to give us a definition of documentary – a genre which can be very difficult to pin down. Here’s what some of them had to say about it…

“Oh Jesus, that’s my entire PhD! I always go back to John Grierson, and he called it the creative treatment of actuality.” – Karin Bareman

“I guess it’s something along the lines of interpreting what is out there in the real world through a process of visual investigation.” – Paul Lowe

“F*** knows? Since the inception of the term, people have rebelled against it. My colleague refers to it as ‘non-fiction photography’ – it’s not about what something is, it’s about what something isn’t. Whatever you want to make it, I suppose.” – Jack Latham

“A horrible question. It’s really about connecting to the real in some way, so some aspect is based in reality – real environments, real issues, real people.” – Lisa Barnard

“I don’t really have a definition, all I can do is tell people what I do. I record something that reminds me of accurately of the essence of what I saw and found interesting – then I show it to other people and hope they find it interesting enough to buy it.” – David Hurn

“It’s a way of photographing what really matters.” – Ken Grant

“Hearing the voice of the people rather than the voice of the establishment telling us what we should be doing. In its purest form, that would be my definition – seeing the world from the bottom up.” – Daniel Meadows

Further reading

Best photography exhibitions to see in 2023