We all remember and rightly celebrate the cameras that changed the game. The Canon EOS 5D Mark II for bringing high-quality video to the masses. The Fujifilm X100 for its brand-reviving retro cool. The Sony A7S for its low-light magic.

But for every successful revolution, there are a litany of failed ones. Here, we’re looking at the camera experiments that bombed and failed to change the market. You can laud the ambition here; many of these cameras are nothing if not brave swings, attempts to shake up the status quo and do something different. Ultimately though, all of them became cautionary tales.

So, let’s take a look back at some of the camera industry’s biggest missteps – the camera experiments that failed to change the market…

1. Nikon 1

It really could have worked. A high-speed mirrorless system with phase-detection autofocus and 60fps shooting, in the year 2011 – it could have been the runaway hit that changed things forever. But the Nikon 1 system, while prophetic in some ways, ultimately made a number of fatal design errors that ensured it was consigned to the dustbin of history (a.k.a. eBay).

The system initially consisted of the Nikon 1 V1 and J1, two diminutive cameras that used their own proprietary lens mount and a new bespoke sensor size – a 13.2 x 8.8mm sensor that Nikon called ‘CX’, and was about a quarter of the size of APS-C. ‘That sounds incredibly small,’ you might be thinking, and you are correct. It was. The small sensors may have been fast to read, but they were incredibly noisy, and this wasn’t helped by the rather pedestrian kit lenses the system launched with.

Part of the problem was marketing. DSLRs were still the big game in town, and rather than pitching the 1 series as a replacement or even a complement to a DSLR, Nikon went around telling people that the 1 series was aimed at people who didn’t want a DSLR at all. And it turns out that ‘people who want a camera, but don’t want the current most popular format of camera’ is a pretty small slice of pie to bet an entire system on. While the 1 series wasn’t an immediate failure – it limped on until 2014 – Nikon ultimately relaunched its mirrorless bid with the far superior Z system.

2. Android cameras

I remember it felt like a glimpse of the future when the Samsung Galaxy NX arrived at the AP office, with Android pre-installed as its operating system, and even a free copy of Lightroom thrown in for good measure. Samsung had already tried it once with the Galaxy Camera, but this felt like a much more serious product. Soon, surely all cameras would be like this, able to download and use apps just like our phones could?

No. There were other attempts, like the Nikon Coolpix S800c and more recently, the Zeiss ZX1, but with Samsung long since out of the camera game completely, it is safe to say that Android-enabled cameras have not caught on.

Why? Well, once you get over the initial excitement of Android on a camera, it’s just not clear what problem it is actually solving. A camera’s touchscreen, it turns out, is an awkward and fiddly place to do anything other than operate a camera. Sure, I could use the Maps app on the Galaxy NX to find my next shooting location – but I could also do that much more efficiently on the phone that I carry everywhere with me, which would also prevent me from accidentally ending my day’s shoot by running down my camera’s battery. Switching between my camera and phone just isn’t particularly a hardship, so the trade-off of a buggy camera system that hogs battery and simply loves to crash is not worth it.

(Also, having Lightroom installed on your camera is the sort of thing that only sounds cool to someone who has never actually tried to use Lightroom on a camera.)

3. Sony QX

These days, smartphones and cameras have reached something of an uneasy stalemate. In the 2010s, however, the prospect of everyone having a serviceable digital camera in their pocket was causing the photo industry to have a not-entirely-unjustified existential crisis. This caused manufacturers to take a few wild swings, some of which, we can now admit, were very funny. Step forward, Sony QX.

So, this. What is this? Well, it’s a screen-free camera that physically clips to your smartphone, and connects to it wirelessly. Essentially, it’s an absurdly bulky upgrade to your phone camera, one that is fiddly to attach, slow to connect, and prevents your smartphone from fitting in your pocket. Sound good? No? No.

I actually owned one of these – Sony gave them away free to journalists at the launch, which isn’t what you’d call a sign of robust confidence in the product. I took it on a trip, and the people I was with found it extremely funny that it took me several minutes of fiddling every time I wanted to take a single photo. I think that was the point I knew the QX was doomed.

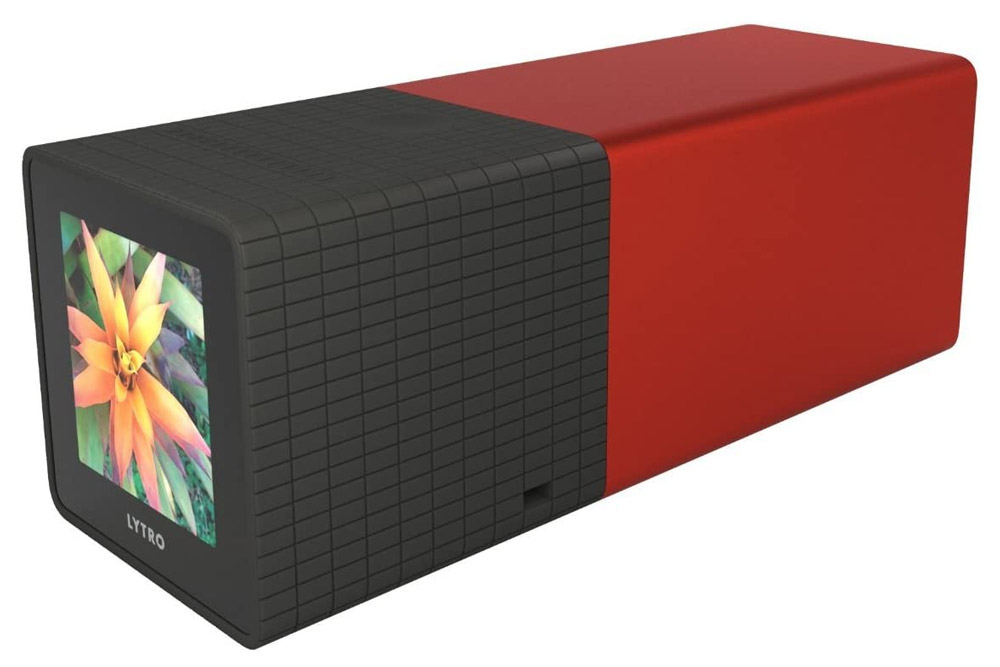

4. Lytro Light Field cameras

Lytro’s ‘light field’ technology was another one of those inventions that felt apocalyptic at the time. Somehow, this little camera that looked like a tube of lipstick was able to capture a stunning level of rich detail from a scene, and thereby enabling you to radically change the focal point of an image after it was captured. Surely, this meant photography as we knew it was over? Why would anyone need to learn how to focus a lens again?

However, the first Lytro camera almost immediately foundered when photographers learned that it produced images with a paltry 1.2MP of resolution. It looked and felt like a toy, but still came with a price tag in the hundreds, and it just wasn’t clear who exactly that would appeal to. Plus, with autofocus systems constantly improving, nailing the correct focus on an image increasingly just wasn’t that difficult, meaning the Lytro wasn’t solving some burning problem.

Lytro attempted to course-correct with the Lytro Illum, which looked and felt a lot more like a proper camera. However, it came with a correspondingly hefty price increase, and the images were still limited to 4MP, which felt paltry even for 2014. The company attempted to pivot away from consumer cameras and into VR, but to no avail, and in 2018 it ceased operations.

5. Lifelogging cameras

In the early 2010s, there was a palpable sense that ‘lifelogging’ was going to become the new hotness. The idea of constantly worn cameras recording a person’s day-to-day existence, by taking photos at intermittent intervals, had a certain cachet among tech startups, and several companies sprung up to meet the perceived demand.

A Swedish startup called Narrative developed the Narrative Clip, a little clip-on wearable camera. Another company called OMG Life developed a similar device called the Autographer. And tech giant Google muscled in on the action with its long-awaited Google Glass smart glasses, which included a 5MP camera.

Ultimately though, nobody managed to make fetch happen. Even setting aside that the image quality from all of these cameras was pretty poor, lifelogging cameras never solved their two most intractable conceptual problems:

1. Most people’s day-to-day lives are not that interesting.

2. Most people spend their day-to-day lives surrounded by other people, who don’t like being constantly recorded.

Google Glass was roundly mocked, and was discontinued in 2015. Narrative and OMG Life both ceased operations in 2016.

Of course, while it’s not exactly the same thing, Ray-Ban’s Meta Smart Glasses have drawn comparisons to Google Glass. We’ve also seen more attempted camera revolutions, most recently the AI-powered Rabbit R1, which doesn’t exactly seem poised to take the market by storm. It seems if there’s a lesson here, it’s that gimmick cameras don’t tend to change the world as much as their hypemen say they will.

For more great guides to cameras, including good cameras that actually did change the market, have a look at our latest buying guides, or the latest reviews. Or check out our list of the Worst Digital Cameras ever released.