Christopher Williams is a conceptual artist that seems obsessed with subverting the conventions of everything he comes across. His photographs often expose areas of image production you would never normally see, from cross sections of the insides of equipment, to photographic scenes that expose the methods behind producing the images themselves.

Described as, “somewhere between a film director, a picture editor and an art historian,” Williams has been taking photographs for 35 years, that question conventions of commercial photography, graphic arts, design and architecture, and often reference other artists and visual works.

His artistic expression often expands beyond the images themselves, to encompass everything from the exhibition space to his press releases. With Williams, even the exhibition catalogue becomes part of the work, to challenge visitors with unexpected breaks from the convention of what they would expect.

The new exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery will be the first major retrospective of some of Williams’s best work, and expect to see something interesting. We talked to Lydia Yee, Chief Curator of the Whitechapel Gallery, to find out more about Williams and the exhibition.

Can you tell us a little about Williams’s career?

Christopher Williams studied at the California Institute of the Arts in the late 1970s under the first generation of West Coast conceptual artists, including Michael Asher, John Baldessari and Douglas Huebler.

Since 2008, he has been Professor of Photography at the Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf, a position previously held by Bernd Becher. In recent years, Williams has had more exposure in public institutions in Europe than in the United States.

The Production Line of Happiness is his first retrospective and the Whitechapel Gallery is the only European venue for the exhibition, following presentations at the Art Institute of Chicago and The Museum of Modern Art.

For the two volumes designed and published on the occasion of this touring survey, Williams received the 2014 Photography Catalogue of the Year, presented by the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards.

Christopher Williams Mustafa Kinte (Gambia), Camera: Makina 67 506347 … Dirk Schaper Studio, Berlin, July 20, 2007 2008 Private Collection, London Image courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and David Zwirner, New York/London

What do you think Williams’s ethos is an artist?

Williams’s rigorous practice can be situated between the overlapping discourses of art and photography. He is concerned with the uses and techniques of photography – in advertising, fashion, industry, science, photojournalism, etc. – but also with revealing the apparatuses of artistic production, circulation, presentation and preservation.

Christopher Williams Untitled (Study in Gray), 1967 Citroen DS, Serial number: DS851360a, Color code: AC 118, Color name: gris etna, Color year: 1966, Studio Rhein Verlag, Düsseldorf, November 11, 2013 2014 Image courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne; and David Zwirner, New York/London

Williams’s career has spanned 35 years. From such a wealth of material, how were images selected for inclusion in his retrospective exhibition?

The exhibition features more than 50 photographs and, while this may not seem like a huge number of images, the curators have made a thorough representation from the major bodies of work that Williams has produced since his days at CalArts. When you see the photographs, I think you can tell that Williams works quite slowly and methodically.

Christopher Williams Bouquet, for Bas Jan Ader and Christopher D’Arcangelo 1991 Tate Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 2007 Image courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and David Zwirner, New York/London

What would a visitor get out of visiting the exhibition?

I think the visitor will initially be struck by the beauty and precision of Williams’s images, not dissimilar to those in high-end fashion or product photography.

Those who look more closely will be rewarded by intriguing details – the prominent freckles and dirty feet of a model or a blemish on a beautifully ripe apple – which defy the logic of this type of photography.

Looking is important because the artist has chosen not to present the standard wall texts and signage next to the work.

Christopher Williams Bergische Bauernscheune, Junkersholz, Leichlingen, September 29, 2009 2010 Private Collection, Belgium Image courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and David Zwirner, New York/London

I read in one of the essays included in the catalogue, that Williams often makes the exhibition space a work of art in itself to suit the architecture of the venue, and to challenge the usual ways of displaying images. Can we expect to see that here?

The display will depart from the customary practices you would typically expect in a public gallery. Williams will leave behind traces of the previous Whitechapel exhibition and install temporary walls from three museums in Germany. Most likely he will hang the photographs lower than the standard eye level and will not necessarily centre the works on the wall.

![Christopher Williams Standardpose [Standard Pose], 1,0 Zwerg---Brabanter, silber, Düsseldorf 2013 (Vera Spix, Elsdorf), Ring number: EE-D13 13--901, green. Studio Rhein Verlag, Düsseldorf, November 21, 2013 2014 Private Collection, London Image courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and David Zwirner, New York/London](/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/03/Christopher-Williams-.-Standard-Pose-Rooster-2014.jpg)

Christopher Williams Standardpose [Standard Pose], 1,0 Zwerg—Brabanter, silber, Düsseldorf 2013 (Vera Spix, Elsdorf), Ring number: EE-D13 13–901, green. Studio Rhein Verlag, Düsseldorf, November 21, 2013 2014 Private Collection, London Image courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and David Zwirner, New York/London

In the past Williams has included press materials and exhibition catalogues as an extension of his artwork. Is this exhibition’s catalogue also a work of conceptual art, as from the preview I was given, I notice it had some unusual elements to it?

The catalogue functions as a publication which includes essays on the Williams’s work, but it is more akin to an artist’s book. Like the exhibition, the catalogue makes us aware of the standard design conventions. The cover, for example, does not include a reproduction of the artist’s work or even his name. Instead, it features and explains two elements that you would normally see on a catalogue cover but not necessarily scrutinise: the product barcode and the institution’s and publisher’s logos.

Christopher Williams K-Line, Matt Dulling Spray, CFC Free … Studio Rhein Verlag, Düsseldorf, August 24, 2014 2014 Private Collection, Germany Image courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and David Zwirner, New York/London

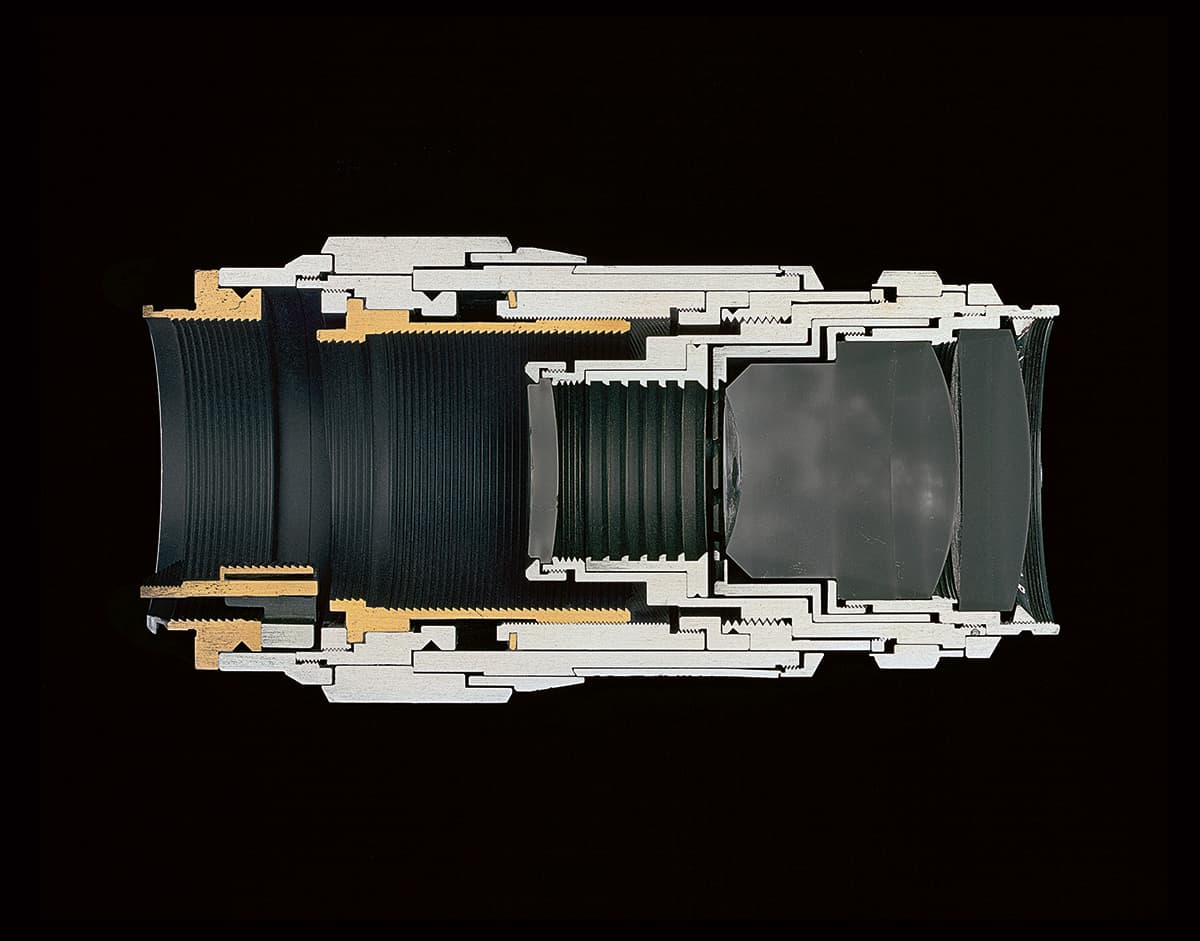

Williams seems fascinated with the workings of cameras and of photography itself, many of his images show cross-sections of lenses, or expose the inner goings on of producing the image. What is it that fascinates him, and what are his images trying to say to us?

The cross-section of the camera lens is emblematic of Williams’s practice. He is in essence exposing the inner workings of photography as well as what takes place beyond the frame.

Christopher Williams Cutaway model Leica Leitz Wetzlar Tele—Elmar 135/4.0 .. Studio Rhein Verlag, Düsseldorf, March 14, 2013 2014 Jay Smith and Laura Rapp Collection, Toronto Image courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne and David Zwirner, New York/London

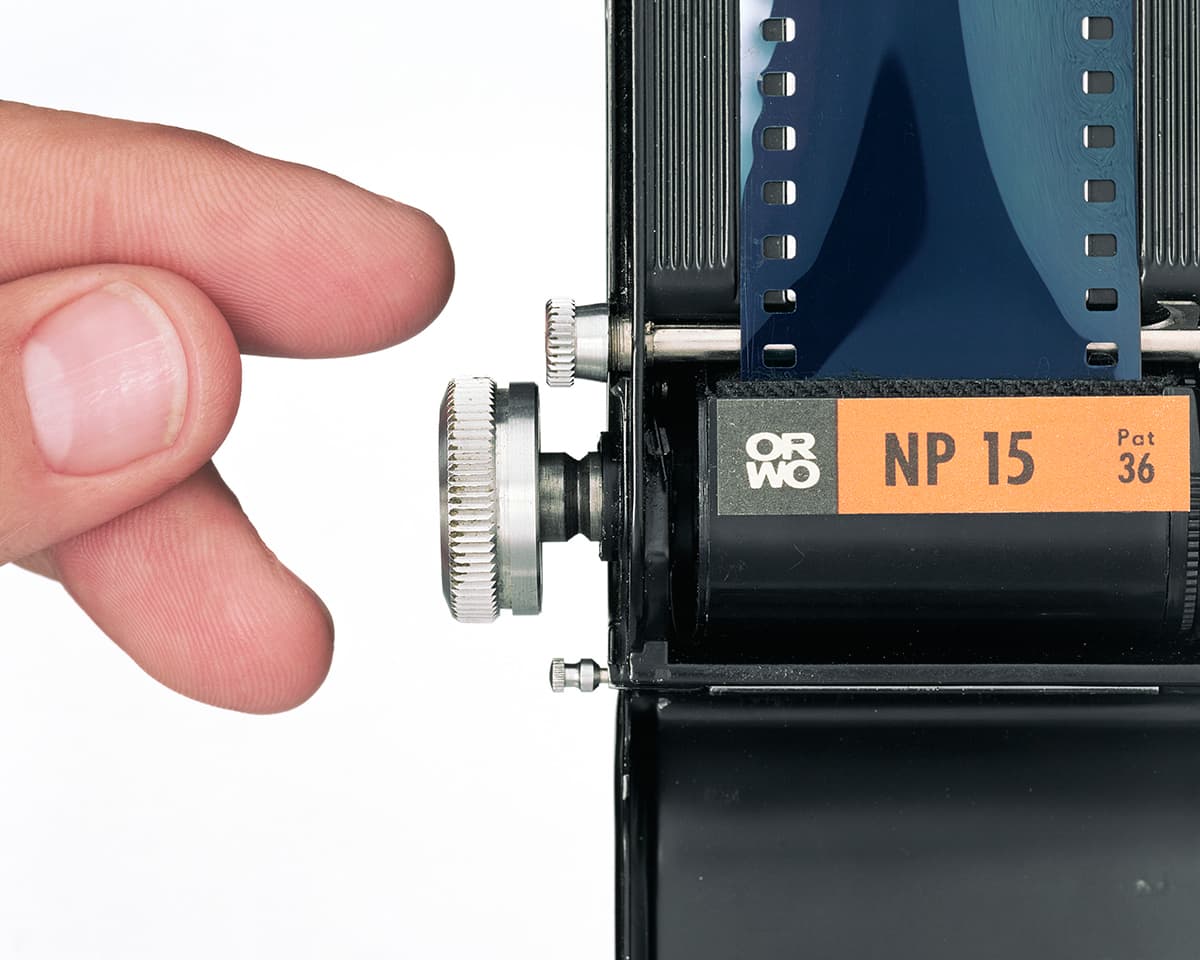

I’ve heard that Williams doesn’t hold the camera or develop the images himself, but he is clearly obsessed with cameras and the technical processes of photography. Can you tell us a little about Williams’s own methods for creating an image?

Williams’s methods mirror those of the advertising or commercial photographer and may involve casting, research, scouting locations, renting studios, selecting props, etc. His images are very carefully composed and crafted, but it isn’t ultimately necessary for him to release the shutter himself.

Christopher Williams Fig. 2: Loading the film (ORWO NP15 135-35 ASA 25, Manufactured by VEB Filmfabrik Wolfen, Wolfen, German Democratic Republic) … Model: Christoph Boland, Studio Thomas Borho, Oberkasseler Str. 39, Düsseldorf, Germany, June 25, 2012 2012 Friedrich Christian Flick CollectionImage courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne; and David Zwirner, New York/London

The Production Line of Happiness exhibition opens at the Whitechapel Gallery, London from 29th April till 21st June 2015. Entry is free. For more information visit the Whitechapel Gallery website