The year is 2024 and that means it’s the 20th anniversary of something very important. No, I’m not talking about the launch of Facebook, or even the landing of NASA’s Opportunity and Spirit rovers on the face of Mars. In fact, it’s 20 years since the birth of the Epson R-D1, the world’s first digital rangefinder – and quite possibly the most amazing digital camera you’ve never heard of.

Even if you do know all about the Epson R-D1, the chances are you’ve never seen one in the flesh. Based on the Voigtlander Bessa-R series of 35mm film rangefinders, and specifically the ‘R-2’, it’s a camera that doesn’t look, feel, or shoot like it’s from this century. And of course that is a huge part of its appeal.

In case you’re not familiar with the Epson R-D1, in a nutshell, it’s an M-mount digital rangefinder with a 6MP APS-C sensor, a small articulated screen on the back, and a unique analogue status display on top, more on this below.

Epson R-D1 – At a glance

- $2999 body only at launch (c $1500-2000 now)

- 23.7×15.6mm CCD, APS-C format

- Type M lens mount

- 6.1MP (3008×2000)

- Double-inverted Galileo viewfinder (1.0x magnification)

- ISO 200 to 1600

- Manual focus

- 2in LCD, 235k dot

- Single card slot (SD, 2GB max)

Created in an eyebrow-raising collaboration between the Seiko Epson corporation and Cosina, the R-D1 certainly surprised the industry and created an impressive milestone, but the lack of an ‘R-D2’ tells you it was far less successful in terms of sales. Barring a couple of updates in the shape of the R-D1s and R-D1x, by 2014, the project had floundered.

A lot to Leica

It’s clear that, while everyone expected Leica to make the first digital rangefinder, having been pipped to the post by a couple of years, the red-dotters didn’t lose their heads and go back to making microscopes. No, for all the R-D1 had going for it, Leica probably looked at the camera’s $3000-body-only launch price, its 10,000 production run and Epson’s lack of conviction in marketing it, shrugged and went back to their currywurst. 2006 and the M8 soon rolled around.

It’s also fair to say people were, and still are, justifiably confused by the camera’s Epson branding, with Jessop’s stores ringing to cries of “hey, don’t they make printers?” And yet… despite its lack of success, the camera has remained prized by those who know about it and appreciate its charms.

I’ve owned an R-D1 for over 10 years, meaning that it was obsolete when I first laid paws on it. But one man’s obsolescence is another’s passion. And though I’ve always shot anything people were paying for on Nikon full-frame DSLRs and mirrorless bodies, the R-D1 has often been my body of choice on a host of city breaks and short trips, or other moments when I’m thinking more about the enjoyment of photography than the end result. It’s just that kind of camera.

But is it any good?

Let’s examine whether the Epson R-D1 is worth your time in 2024. And that means adding some empiricism to the emotion. We can start by saying that even though the R-D1’s 6.1MP APS-C format CCD chip now looks dangerously anaemic, it was certainly not under-spec’d for its time. The pixel count pitched it in with the likes of Canon’s 10D and Nikon’s D70, and full-frame sensors were still a rarity outside of Canon’s professional bodies, until the democratising EOS 5D arrived in 2005.

Today, the R-D1’s 3008×2000 images are fine for posting online or making medium sized prints, but of course that resolution means that cropping options are limited. Nor is the sensor’s dynamic range up to modern levels, so a little more care needs to be taken in exposure and filtering when dealing with contrasty scenes. That said, I’ve always found the images from it to be pleasing in colour and tone. Over the years I’ve tended to use it for simple shots, and maybe the fact that I enjoy using it so much adds some abstract pleasure to the resulting images.

The sensor has an ISO range of 200-1600 and it’s fair to say images show grain throughout. At ISO 800 and 1600, this is quite noticeable, even at such a small resolution. But it’s not unpleasant in the way some sensors of the age showed lots of banding at high levels. And today we have software like DxO PureRAW 4 that does a great job of removing noise and improving detail, so while the images remain small, they’re much cleaner.

Out of the box, the R-D1 can’t shoot Raw+JPEG, but this can be added by installing the firmware for its 2006 variant, the R-D1s. That firmware also adds improved magnification functions on the LCD screen, as the original could only zoom into 2x for Raw images, which was bloody awful, and 10x for JPEGs; both are improved to x16 which, when I activated it in 2015, was a revelation. There’s also a Quick View option that brings images up on screen straight after shooting and some other improvements like improved auto white balance. I could be wrong, but I don’t remember many other cameras in 2004 having upgradable firmware like this, so fair play to Epson there.

To update the firmware and do plenty of other stuff you need to access the menu, and that’s where things really lurch away from modernity. First you have to press a button to activate the titchy 2in LCD screen. Next press the Menu button, to reveal a load of icons in a circle. To navigate these, you use the camera’s Jog wheel that sits on the left of the top plate, where the film-rewind crank on a Bessa-R would be. Fortunately items are titled and despite feeling thoroughly arcane at first, it’s soon second nature to spin through them, if not particularly fast. In fact, once mastered, the menu system is fun. It’s like you’re sharing an inside joke with the designers.

Using the camera for photography

That heading might seem weird, but hopefully it’ll make sense in a bit. For now, know that the R-D1 has all the stuff needed to take good, if small, pictures.

Sure, there’s no autofocus, but people have been coping with that since the 1800s. As mentioned it can shoot Raw (at 12-bit), you can change the white balance, and apply user-defined colour effects to JPEG images. There’s a black & white mode with several colour filter settings, too. And that’s about it. None of the clutter of modern supercomputers masquerading as cameras. Just good honest basics. This lack of options is actually pretty freeing when you use the camera. It helps the connection to photography and feels like you’re using a photographic tool, rather than a piece of technology.

Talking of the basics, I’ve only ever had one lens to use with the R-D1, a Voigtlander Ultron 35mm f/1.7 Aspherical. That’s right, in an additional nose-thumbing to the Germans, the R-D1 uses Leica’s M-mount. This Ultron is a great lens, not all that sharp wide open, but good at f/2 and beyond. And as the R-D1 has an APS-C format sensor, it gives a 53mm equivalent, which is helpfully spelled out on the rear of the flip-over LCD screen, along with other common focal lengths you might mount. If you had the money.

Allied to all this is the Frame Selector lever on the top plate. There are three settings, 50, 28 and 35, which correspond to the actual focal length of the lens you’re using, not the equivalent. Framing through the viewfinder using the guide is fairly accurate with just a 10% or so extra at the edges.

Should I be able to afford any additional M-mount lenses, I always assumed it would be difficult to frame with any degree of accuracy while not having a relevant guide, but maybe it’s something you get used to. I have never used the 50mm or 24mm settings. They are a mystery to me. I did foolishly think that my Nikon F mount 24mm f/2 AI lens could be mounted via an F to M converter. Don’t be silly, Kingsley, that’s not how rangefinder lenses work, and you’ve just given Amazon another £25 in error.

Focusing using the traditional ‘patch’ in the middle of the frame is easy, wherein two partial images overlap at the turn of the lens’s focus ring. But people invented autofocus for a reason, and working wide open with a rangefinder like this, it’s always possible to miss focus by a bit. It can be frustrating, but also part of the charm. After all, this isn’t a camera that’s about critical sharpness on a moving eyeball. Some of the old tricks can help, like stopping down and zone focusing. But as I say, I’ve never used the camera for anything more critical than wandering the walls of a crumbly European city.

Elsewhere, the R-D1 has enough manual inputs on the body to do all you need. There’s a lockable physical shutter speed dial that runs from 1sec to 1/2000sec, includes a Bulb setting, and also an Auto Exposure setting that can be biassed up to +/-2EV. If you pull up the dial you can rotate through the four stops of ISO, and while it’s a bit tricky to see the numbers with my ageing eyes, the fact there are only four settings means you don’t get lost. On the back there’s a lever to set white balance and image quality, an AE-Lock button and an assignable User button, which can be set to a vanishing small range of options, one of which is ‘Print.’ Yes, Epson, we see you.

For metering, it uses a basic and reliable centre-weighted system, so you naturally need to be aware of the exposure being thrown by very light or dark scenes. Moving back in time from the simplicity of mirrorless can be alarming in that way, but I find my brain soon switches back.

A half press of the shutter release brings up a red exposure indicator within the viewfinder as a guide. I tend to shoot in AE, and just watch for too much of a dip in speed. As before, the benefits of a mirrorless camera’s auto ISO or in-body image stabilisation are the stuff of fantasy here.

Then there are the top-plate’s dials, which we’ll come onto next.

Using the camera for pleasure

Ah, those dials. To paraphrase Shakespear, “let us sit upon the ground and tell glad stories of the R-D1’s spinning things.” They don’t do anything to improve images, but they are a wonder. What I call the small window of dreams, Epson more prosaically terms the Status Gauge.

These dials are the gift of Epson’s partner, Seiko. The story goes that during the camera’s early development phase, one of Seiko’s designers burst into the room and shouted “Lads, trust me, put a clock on it.” Of course, he was thrown out of the company. But through several revisions, his idea became four gauges showing white balance, image quality (Normal, High, Raw), battery status from Full to Empty, and around those a frame counter from 500 to 0.

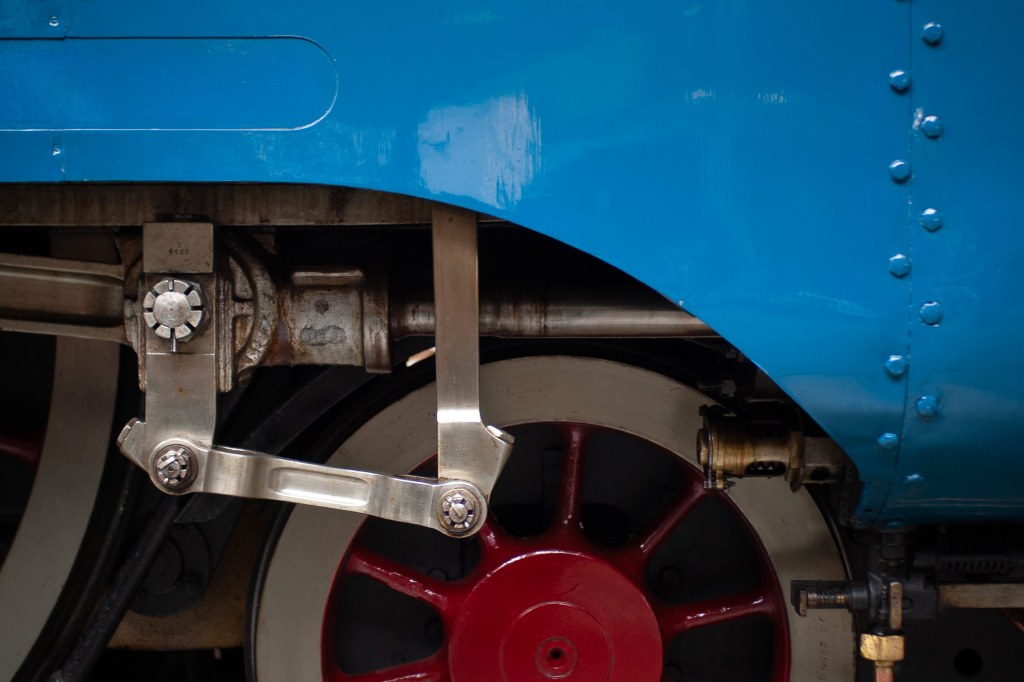

Am I silly getting excited by small dials? No. This is where it’s important to think about how a camera makes you feel. I love those dials. Switch on the R-D1 and watch them gliding into place with wonderful precision. They connect you with the camera’s inner workings. Their analogue nature gives you the feeling of using a true vintage body. It’s like observing the fine mechanics of a steam train, or the gauges on a vintage fighter plane. Geeks and dials. They’re made for each other.

Are you winding me up?

With the Epson R-D1, the idiosyncrasies don’t end there. The camera’s most wonderfully anachronistic feature is its Shutter Charge Lever, basically identical to the Film Advance Lever on the Bessa-R. This is not for show. You literally have to wind on between frames, or rather cock the mechanical shutter. Otherwise you won’t be taking any pictures.

When I first used the camera, I found this absolutely charming. Then after missing multiple shots because I’d not remembered to use it, that changed to incredibly frustrating. Subsequently I noticed that, when the lever hasn’t been advanced, the exposure guide is switched off in the viewfinder as a warning. Smart. Now, a decade or so on, we’re at peace, like an old couple who’ve knocked the rough edges off each other. I even remember not to put the camera to bed without first releasing its tension.

It’s quite possible that choosing to use a mechanical shutter cocking lever was cheaper and more expedient than designing an electronic method. Or that there were a lot of Bessa-Rs hanging about that could be cannibalised. Either way, I’m thankful for it, and so is every person that uses the camera when I let them. Of course, this also means that the R-D1 is also one of the only digital cameras that doesn’t have a continuous drive setting. Again, it’s about how that makes you feel. Slow down and wait.

The digital film camera

Briefly going back to the R-D1’s LCD screen, here’s why its design further enhances the camera’s appeal. Yes, the actual LCD is nothing special by modern standards. It’s small, not easy to read and scratches easily. But in flipping it over and hiding it within the body, the camera looks almost totally like a film model. It’s as though that dubious idea of lobbing a sensor into the film bay of your beloved old camera has come to life.

Why does this matter? Most street shooters favour anonymity, and though I’m not really one of the candid clan, I’ve seen the benefit of someone not bothering you while you shoot. Anecdotally, I took the R-D1 to Palermo in Sicily in about 2015. Having wandered into the wrong part of town, I was pretty sure I was about to be mugged, but the mafiosos took one look at the camera and didn’t react at all. Perhaps they thought it was a worthless film camera. Or maybe, on a hot day they simply couldn’t be bothered to shed blood over a 6-megapixel oddity. “Fuori di qui! Cosa farò con una fotocamera da 6 megapixel, stupido!”

At 590g and measuring 142x89x40mm, the camera isn’t small, or light, and has a lot of magnesium alloy in it, so perhaps I could have used it to fend them off. We’ll never know.

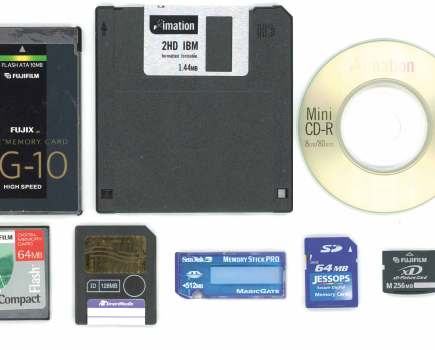

This reminds me that, if travelling, it’s well worth remembering that the R-D1 can only take regular SD cards, not the larger SDHC or SDXC versions, so you’re limited to sizes of up to 2GB. That sounds like a lot, but with 10MB Raws, the card can fill up pretty quick, and it’s trickier that you might think of finding those older cards at short notice in a foreign city. Nor is there USB charging to keep you shooting, but the battery lasts well. It should, it’s not doing much.

Epson R-D1 – A conclusion of sorts

So where does that leave us? It’s true that using the R-D1 today for much other than the pure enjoyment of picture taking can be a problem. But if all you want to do is connect with photography and occasionally have people ask why you don’t buy a proper camera, it’s perfect.

Looking at the popularity of cameras like the Fujifilm X-Pro series that debuted in 2012, and Nikon’s Df and latterly the Zfc and Nikon Zf, it’s obvious that cameras with vintage nods and modern features remain popular, so it’s a real shame we never saw an R-D2. Even doubling the resolution and adding a few more modern features like a broader ISO range and in-body image stabilisation would create an incredible camera.

The R-D1’s camera’s looks and handling, its contrarian features and its build quality make it a joy to use. And all that enjoyment flies in the face of its idiosyncrasies and subtle, early digital comedy. It can be baffling to newcomers, but when you learn its intricacies, that’s one of the things that appeals so much about it, like being a fan of a band no-one else knows, or owning a fabulously unfashionable and unreliable vintage car, both of which I’ve subscribed to. If I had to go back into a burning building for one camera, this would probably be it.

Related reading:

- Vintage digital cameras you should actually buy

- The best vintage lenses to get the retro look

- Vintage cameras: collectable, usable and affordable

- How to buy pre-owned vintage camera equipment

- Get great shots with vintage lenses

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.