To mark the opening of his new exhibition at Saatchi Gallery, London, Edward Burtynsky talks to Tracy Calder about fishing, photography, eco-anxiety and the benefits of being a perfectionist.

When Edward Burtynsky was a child, he grew up to the soundtrack of the General Motors plant in St Catharines, Ontario. ‘We would drive past and all you could hear was ba-boom, ba-boom,’ he recalls as we settle down for a chat. St Catharines was a blue-collar city and his father, Peter, had secured work on the production line at the factory. ‘There was a red brick wall that ran for about half a kilometre and from behind it there came a noise so loud that you could feel the earth shake,’ he explains. When Edward was seven, he attended an open day at the plant and was amazed by what he found there. ‘I saw molten metal going down chutes, big presses in action and people wearing aluminium suits that made them look like Martians,’ he laughs.

All the while, ba-boom, ba-boom rang out like a heartbeat. To a child born at the beginning of the Space Race, this odd environment where humans and technology worked side by side must have seemed intoxicating. ‘I realised that there was this whole other world,’ he

says. ‘It was like going into the bowels of the machine while knowing that every time we drove past, we were riding in the thing the plant was making!’

Edward received his first camera at the age of 11 (a gift from his father, who was a keen amateur photographer), but it would be more than two decades before the ‘man-altered landscape’ became his primary focus. By then, he had put himself through college and university by working in factories, just like his father. All that changed in the early eighties. ‘Recently I came across a journal from 1983 which contains a paragraph where

I define my life’s work,’ he smiles.

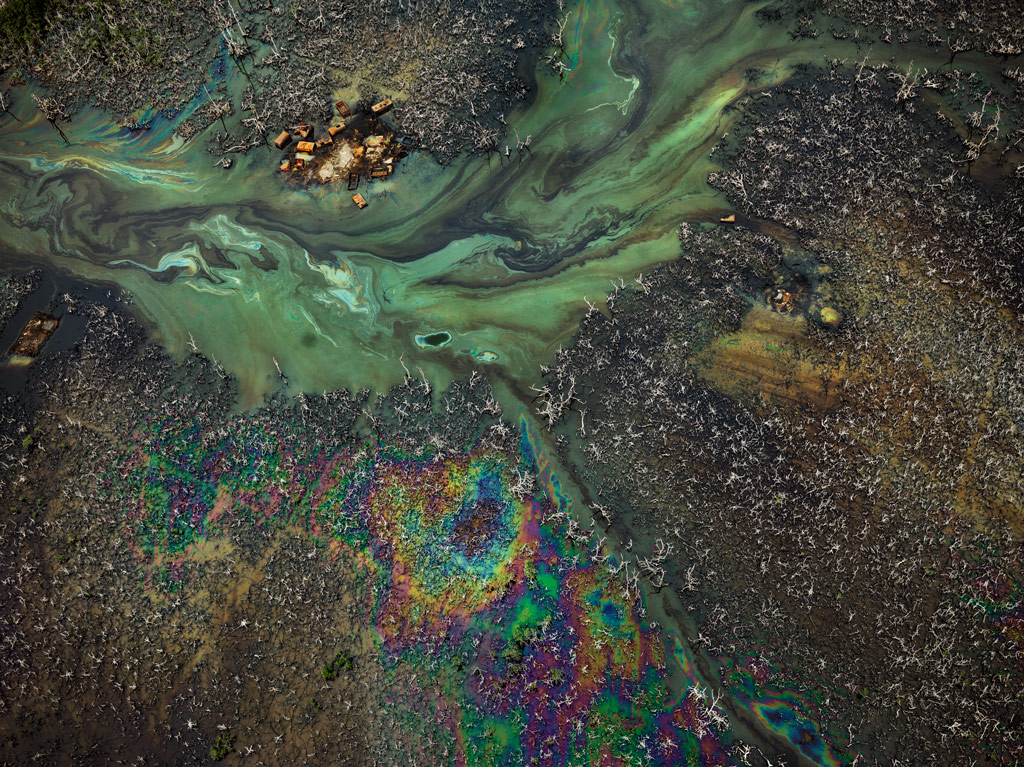

At the time, Edward was on a solo trip across North America (partly funded by an arts grant), travelling with a 5x4in camera, a stack of film, a tent, fishing gear and some money for petrol. ‘I fished and photographed for four months,’ he grins. Halfway through the trip he began making notes about the trajectory of human population growth. ‘I was looking at the scale of resource extraction and all the technology that accompanies human expansion and I was thinking how frightening and unsustainable it was,’ he recalls. ‘I decided to find the largest examples of the human footprint and to make photographing them my life’s work.’

Nothing less than perfect

Speaking to Edward, his ambition is clear. In 1985 he opened a laboratory where he created prints for himself and some of the best-known photographers in the country. ‘I learnt how to print, I learnt about what made a good image, I was the first in line for new optics, and I ran the chemistry,’ he says. ‘I knew how it all worked, so I became a highly skilled technician in the field of printing.’

Edward refused to settle for anything less than perfect, and this attention to detail still underpins his work today. ‘I wanted to be at the leading edge; at the point where you couldn’t make it better because there was nothing better,’ he enthuses.

He applies the same ‘best of the best’ approach when it comes to selecting subject matter. Whether he’s shooting mines, salt pans, factories, dams or oil refineries, he’s always looking for the biggest and the best examples. ‘The largest example is where extraordinary things are found,’ he says. ‘It’s where humans are dwarfed in the theatre of our own creation. We become bit players in a world of technology that we’ve built.’

Bearing witness to the impact of human industry on the planet is bound to affect your mental health, and I’m curious to know if Edward has ever suffered from eco-anxiety. ‘Yes,’ he confides. ‘I experienced a kind of grieving in the past, especially towards the end of shooting in India in 2002. Coming across kids that have been born on the streets – nothing prepares you for that.’

Similar feelings arose when Edward visited China around the same time. ‘I saw the ambition people had to rise out of poverty, and it felt like a massive train leaving the station. It frightened me,’ he admits. On one occasion, Edward found himself driving for hours on end through a smouldering landscape. ‘It was like a war had destroyed everything,’ he explains. ‘No tree or mountain was safe. It was a scorched earth.’

Witnessing such an assault on the land must have been painful, but Edward used his grief to sharpen his focus. ‘Like any grieving process, when you come out the other side and go on with life you take the grieving and you convert it into meaning – that’s the way out, it’s the only way out,’ he stresses. ‘You become much more meaningful and persistent in your work, and you become clearer in what you want to say and do.’

Edward describes himself as an artist (or agent) trying to raise awareness, but he doesn’t see himself as a preacher or a judge. None of the activities he photographs – from mining to deforestation – are illegal, for example. ‘I don’t want my work to stand as an indictment,’ he says. ‘People say that I photograph disaster aesthetics, but that’s not the case. What I’m photographing is the extension of what it takes to build a city.’ Every large settlement is fed and fuelled by ‘a whole world’ of natural resources and manmade technologies. ‘If you are going to call it a disaster then be careful because this is what we’ve created to give us the life we want,’ he argues.

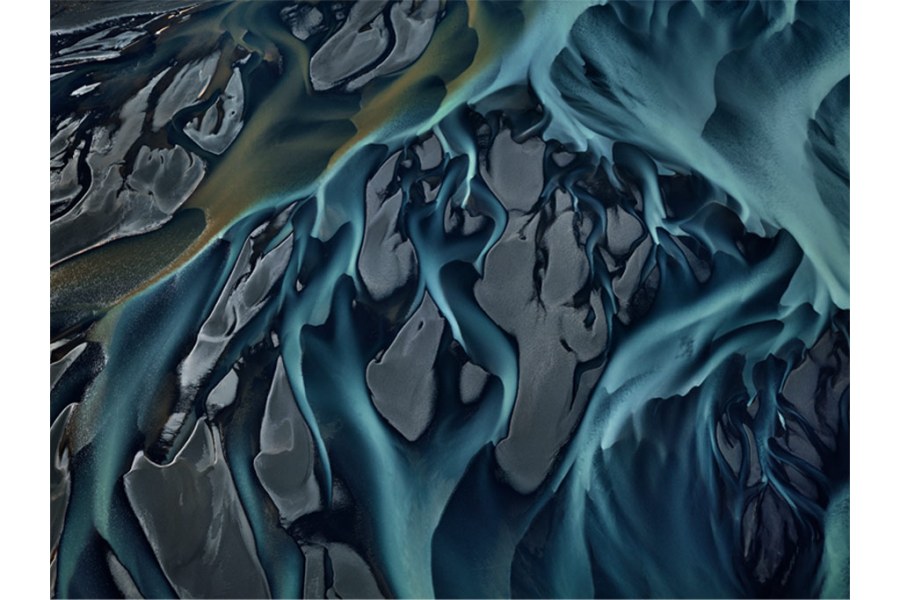

What’s more, there is an undeniable beauty to Edward’s work – colourful organic shapes fill the frame, geometric patterns satisfy the eye, blocks of stone create striking architectural forms – but if we take a moment to read the captions, any sense of wonder is soon replaced by feelings of shock and guilt. ‘What the work tries to do is to bring us to a sober and rational understanding of who we are and what we’re doing,’ says Edward. ‘It’s not trying to say who’s right and who’s wrong.’

Drawing on painting

One of the things that makes Edward’s work so aesthetically beautiful is an understanding of art history, and a knowledge of painting. ‘Caspar David Friedrich was the first romantic painter who elevated the experience of nature,’ he says. ‘He demonstrated that there was more to nature than a pastoral landscape, a field of cattle or a nice tree. For him, gazing into nature was a complete experience.’ Perhaps the romantics knew that they were about to be hit by a wave of technology that would compromise the natural world. ‘They were looking down the barrel of something scary,’ agrees Edward.

In the early days, he was also inspired by Edward Weston, Emmet Gowin, Paul Caponigro and Frederick Sommer. ‘I was influenced by the modernists,’ he reveals. ‘I love the work that Sommer made in the desert where he flattened space.’ Edward realised he could take what Sommer was doing and mix it with the basic fundamentals of abstract expressionism.

‘I went from looking at the modernists to looking at abstract expressionism and wondering how I could marry these guys up,’ he echoes. ‘I wanted to use this knowledge to help me organise the frame and make sense of the world.’

When Edward scribbled down a paragraph that defined his life’s work in 1983, he knew he wanted to make pictures that would be felt and understood for generations. ‘I wanted to produce photographs that had a kind of future forward built into them,’ he says. ‘I wanted there to be something about these pictures that meant that they couldn’t be swept under the rug or ignored.’

On 14 February Saatchi Gallery opened the largest exhibition of his work to date. Looking at the images displayed on its walls, it’s clear to see that Edward has succeeded in his mission. ‘I never had a beautifully laid out life plan,’ he concludes. ‘I just followed my instincts.’

Burtynsky: Extraction/Abstraction runs at Saatchi Gallery until 6 May.

Edward Burtynsky: New Works runs at Flowers Gallery, Cork Street, London until 6 April.

To find out more, visit www.saatchigallery.com, www.flowersgallery.com and www.edwardburtynsky.com.

His book, Extraction/Abstraction, which accompanies the exhibitions, is published by Steidl in June, price £48, ISBN 978-3969993132.

Related reading:

- Rock of ages – exclusive Jill Furmanovsky interview

- Photographing BST Hyde Park with the Nikon Z8

- Inspiring portrait portfolio wins Emerging Talent Award

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.