In his latest column for AP, nature photographer Marsel van Oosten explains how to be creatively proactive in your wildlife and nature photography, and how powerful previsualising ideas can be.

As I’m writing this, I’m on a ship in the Antarctic leading a photo tour to the Falklands, South Georgia and Antarctica. We’re on our way back now to Ushuaia, Argentina, after spending three weeks on and around the wildest and most remote continent on our planet. Antarctica is so inhospitable that, for six months of the year, you can’t even get here because there is too much ice and the conditions are too brutal.

As the distances between our destinations are quite long, we have spent quite a bit of time on the ship sailing from one place to the next. On those days, I have given lectures and we have done many image review sessions during which I analyse the images of our guests and give constructive critique on how to improve them – either in the field or in post-processing.

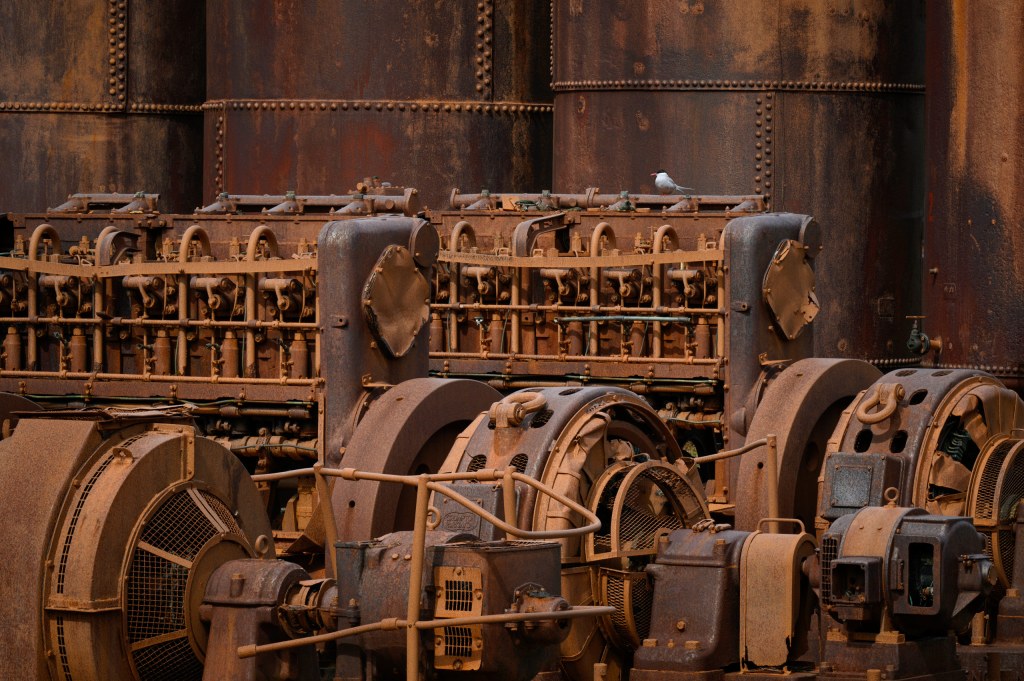

An Arctic tern rests on rusty machinery at an abandoned whaling station, Grytviken, South Georgia Nikon Z9, Nikkor Z 70-200mm f/2.8 at 185mm, 1/50sec at f/16, ISO 64, focus blend, Photo: Marsel van Oosten

During one of these sessions, we talked about something that I have addressed here before: the difference between reactive and proactive photography, and the power of previsualization. Most wildlife photography is reactive: the photographer reacts to what he or she sees. Proactive photography is to previsualise an image, to first create the image in your head and then actively work towards it.

One of our landings on South Georgia was a visit to Grytviken, a former whaling station that closed in 1962. It’s very different from all other landing sites on South Georgia because it’s not wild. It’s full of rusty machinery and whale blubber drums, and there is not as much wildlife there. While very interesting from a historical point of view, it’s not an easy place for a wildlife photographer.

Left: An Arctic tern flies in front of blubber tanks at an old whaling station, Grytviken, South Georgia Nikon Z9, Nikkor Z 70-200mm f/2.8 at 200mm, 1/1600sec at f/13, ISO 800. Photo: Marsel van Oosten

Whaling was once a very popular industry when there were still a lot of whales everywhere in the region. Whalers from various countries around the world built these whaling stations, where the whale blubber was collected and boiled. All the stations closed in the middle of the last century. Grytviken station is the only one that has been preserved as a historical site, all others are off limits because they are dangerous, with lots of asbestos and loose metal sheets etc.

When I set foot on land, I didn’t have a creative plan. I like rusty things because of the colours and the texture, but I had photographed it on previous trips, so I wasn’t keen on doing more of the same. While I was walking around the site, I noticed there were quite a few terns flying around – they are beautiful little birds. And, while I generally don’t really enjoy photographing small birds, I suddenly saw an opportunity to create a series of images featuring terns in this world of metal and rust – nature vs man, pure vs decay. Depressing on the one hand, but with a positive note: in the end, nature will always conquer.

I started searching for terns that were flying close to these huge whale blubber tanks; towers of rusty sheet metal. For three hours, I did only that with my Nikon Z9 and ended up with a series of three images that only consist of two elements: a bird and a ton of rusty metal. I’m very happy with the results because it was not only fun to do, but it is also the result of coming up with a creative idea and then working towards that. Proactive photography will almost always lead to more interesting images than the reactive approach.

Now let’s hope the notorious Drake Passage will be kind to us…

As told to Steve Fairclough.

Marsel van Oosten

Marsel van Oosten was born in The Netherlands and worked as an art director for 15 years. He switched careers to become a photographer and has since won Wildlife Photographer of the Year and Travel Photographer of the Year. He’s a regular contributor to National Geographic and runs nature photography tours around the world. Visit www.squiver.com

Related content:

- How to capture birds in flight and fast-moving animals

- Best cameras for wildlife photography

- How to be an ethical wildlife photographer

- Photographing wildlife by studying animal behaviour

Follow AP on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and TikTok.