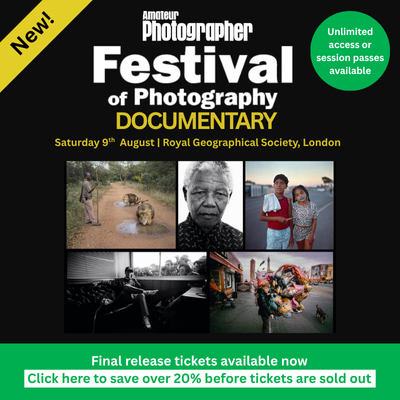

Marsel van Oosten explains how the main subject of your wildlife pictures can be put in context, even if they’re not the biggest creatures in the frame

Marsel van Oosten

Marsel van Oosten was born in The Netherlands and worked as an art director for 15 years. He switched careers to become a photographer and has since won Wildlife Photographer of the Year and Travel Photographer of the Year. He’s a regular contributor to National Geographic and runs nature photography tours around the world. Visit www.squiver.com. In this article, he explains how you can add context to your wildlife subjects.

When you think about wildlife photographers, and the gear they use, you immediately think of huge telephoto lenses. As much as they’d want to, wildlife photographers usually can’t photograph their subjects with a wideangle lens because the wildlife would run away if they tried… or you could die trying.

When you’re photographing an elephant seal, a rhino or a polar bear, you might get away with a short lens and still get the main subject at a recognisable size in the frame. But, especially with smaller subjects, you need a lot more focal length to get them to show up at a decent size in the image.

This is one of the reasons why I prefer to photograph large mammals – they enable me to use shorter lenses and that means I can include a fair amount of the habitat. My favourite wildlife images are so-called ‘animalscapes’, so the habitat is very important to me and I don’t always want to reduce everything to a blur.

Yet that almost inevitably happens when you’re using long telephoto lenses – the longer the lens, the more shallow your depth of field. This is also why I don’t photograph birds much… most of the time the habitat is reduced to a few branches and leaves, and the backgrounds tend to be a smooth blur. From a purely artistic point of view, this doesn’t excite me much.

The tower, Botswana. This giraffe was annoyed by the red-billed oxpeckers that were harassing it. Every now and then it would violently shake its head, which made the birds fly off, only to return a few seconds later Nikon D850, 180-400mm f/4 lens, 1/400sec at f/5.6, ISO 200

When I photograph small subjects, like birds, I’m always looking for ways to include as much of the habitat as possible and, ideally, in a not-so-obvious way. These two images both show oxpeckers in their natural habitat and you could argue whether the oxpeckers are actually the main subject – after all, they are much smaller than the other subjects.

The image with the Cape buffalo started as a buffalo image when I stumbled across it in the Okavango Delta in Botswana. It was covered in drying mud and I was captivated by the monochromatic feel and by the wonderful texture. I started shooting relatively wide, then kept framing it tighter and tighter until I only had the head inside the frame.

It was pretty cool, but something was missing. I started thinking about alternatives and then noticed the oxpeckers hopping from buffalo to buffalo. That’s when I previsualised an image where the buffalo would not be the main subject, but a monochromatic background for the bird.

When analysing my frame I realised that, in order to eliminate distracting highlights and really use the buffalo as a ‘wallpaper’, I needed to go even tighter and get rid of everything that wasn’t a buffalo. That gave me a very nice frame in which the buffalo’s horn was the perfect perch for an oxpecker. From then on, it was just a matter of patience and waiting for it to materialise.

When it did, I shot many images to capture the different poses of the bird. In one of the frames the eyes of the buffalo were closed, and that turned out to be perfect. Our eyes are always drawn to other eyes, so when there are eyes in your photo people can’t resist looking at them. In this case I thought that would just be a distraction.

The beauty and the beast, Botswana. Oxpeckers are after the ticks on their hosts so, originally, they were thought to be an example of mutualism – interaction between individuals of different species that results in positive effects for each. However, evidence suggests oxpeckers are actually parasites Nikon D810, 600mm f/4 lens, 1/1250sec at f/5.6, ISO 320

These buffalo are always followed by oxpeckers, who are after the ticks on the buffalo so usually are around. But also there’s usually quite a few buffalo, so they might not always be on the buffalo that you’re photographing. The name ‘oxpecker’ already implies that it’s not rare to see one on a buffalo.

But you have to try to come up with an idea of how you’re going to photograph this. For example, am I going to leave enough space so that I can see background, that I see trees or sky in the background, or am I going to go close? And, if I go close, how close and where do

I want the bird? For me, this was just the perfect spot in the image for the bird to be.

The other image could be about the oxpeckers or it could be about the giraffe. I like to think it’s about the oxpeckers and the giraffe is just a massive perch. It was shot at sunrise. Usually, in Africa, the sunrises can be very colourful but the colour doesn’t last long. In the afternoons you get a bit more colour because by that time it’s much warmer, there’s more haze and more dust in the air.

Again, the oxpeckers are resting on this giraffe to check constantly for ticks. The moment I have two images next to each other that both feature oxpeckers then, suddenly, the oxpeckers become the subject.

As told to Steve Fairclough

Further reading