Credit: Angela Nicholson

In the earliest days of modern mirrorless cameras, the main claim made for them was that they were smaller and lighter than DSLRs. Dumping the mirror and pentaprism saved lots of space and allowed the lens mount to be moved closer to the sensor, enabling the cameras and lenses to be made smaller. But the first mirrorless system cameras weren’t without issues. Their electronic viewfinders (EVF) lacked in the resolution and refresh-rate department, so they were often viewed as something of a poor relative to optical viewfinders. And their autofocus (AF) systems needed good light to work and could only really cope with stationary subjects.

Thankfully things have moved on a lot in the past 10 years. Mirrorless cameras can still be tiny, but there are also larger models to satisfy those photographers who want larger controls and more space for their hands. EVFs have also improved to the point that they now offer some distinct advantages over optical viewfinders and some of the AF systems are phenomenal. Still need convincing? Read on.

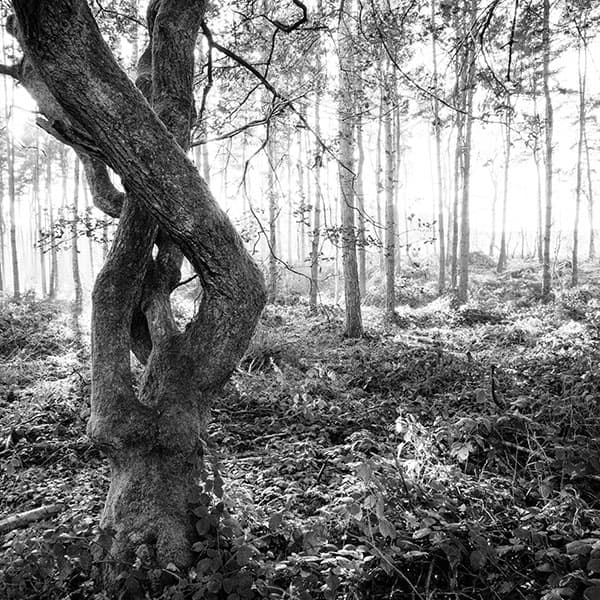

With a WYSIWYG viewfinder you can be sure the colour, white balance and exposure are what you want. Credit: Angela Nicholson

What you see is what you get

One of the most significant advantages of modern mirrorless cameras is that they operate in permanent live view mode. That means they use the imaging sensor to provide the view in the viewfinder and on the main screen on the back of the camera. As a result, they’re able to show the impact of aspects such as exposure, white balance and colour settings. So if you’re shooting in black & white mode with a shutter speed that’s too fast for the conditions, you’ll see a dark monochrome image in the viewfinder and on the screen. And as you adjust the shutter speed closer towards what’s needed, you’ll see the image gradually brighten in the viewfinder. You can use the image in the viewfinder to decide the correct exposure rather than rely on the exposure scale. However, should you need it, there’s also usually a live histogram available to let you assess the brightness distribution.

Many cameras offer aspect ratios of 3:2, 4:3,16:9 and 1:1, but some even have 65:24 like this from the Fujifilm GFX 50R. Credit: Angela Nicholson

Better composition

The electronic nature of the viewfinders in mirrorless cameras allows them to show some useful tools for improving image composition. For example, they can show an electronic level that doesn’t disappear when you half-press the shutter release to focus on the subject. Most offer a few different grid displays that can help with aligning objects in a scene. However my favourite tool after the electronic level is the Aspect Ratio control, which can be found in the main or quick menu. Some DSLRs can indicate the selected aspect ratio with lines, but a mirrorless camera can display the image with the aspect ratio applied properly.

When an aspect ratio other than the sensor’s native setting is used, the JPEG le is cropped in-camera. However the raw file usually has the data from the whole sensor so you can change your mind if you like. You may find that you need to open the image in your raw-editing software and select the crop tool before you see the whole image.

These in-camera aspect-ratio options help to move the decision about aspect ratio to the shooting stage instead of at the editing stage. Rather than waiting to see an image on a computer screen with the cursor hovering over the crop tool, you can look at the scene and view it with different aspect ratios applied in-camera. That might sound like a small point, but a step or two to the left or right can make a significant difference when you swap between the aspect ratios. If you decide at the editing stage, you don’t have the opportunity to take these steps.

Seeing the exposure in the viewfinder can help you capture more interesting images. Credit: Angela Nicholson

Creative use of exposure

Being able to see images as they will be captured can promote using exposure as a creative tool. For instance, there have been occasions when I’ve held a camera to my eye and the exposure settings have been wrong in the traditional sense, but the image looked great – so I’ve taken the shot. Subsequently, I find I experiment more with exposure with mirrorless cameras than I ever do with SLRs. I also love that some camera manufacturers allow you to assign exposure-compensation control to the manual focus ring (or a third ring) of a lens. It makes adjusting and assessing exposure more of a part of the creative process of photography.

Customising the lens ring on a Nikon Z 6 or Z 7

- Press the Menu button and navigate to the Custom Setting Menu. You need section f2: Custom Control Assignment.

- Select the option in the bottom right corner, which is set to M/A by default.

- Select Exposure compensation or Aperture, depending upon which you wish to adjust with the ring. It reverts to manual focusing when it’s needed.

Having more AF points with wider distribution means a camera can track moving subjects around the whole frame. Credit: Angela Nicholson

Better focusing

There was a time when the dedicated phase-detection AF sensor in a DSLR gave it an advantage over a mirrorless camera, but that’s decreasingly the case now. Mirrorless cameras use their imaging sensor for autofocusing, with some having embedded phase-detection pixels and others using contrast detection. These contrast-detection systems are much improved over the versions in the earliest mirrorless cameras. In addition, some cameras use a hybrid system that combines phase detection with contrast detection for the best of both worlds.

Even if your subject is far from the centre of the frame, most mirrorless cameras can get it sharp. Credit: Angela Nicholson

Close to the edge

Using the imaging sensor for focusing allows mirrorless cameras to have AF points further towards the edges of the frame than most DSLRs – especially full-frame models. That’s really useful with off-centre subjects, and there’s no need to focus and recompose. It also means that mirrorless cameras can continue to follow the subject further around the frame which lets you create better compositions in-camera with less need to crop than when you rely on an AF point near the centre of the frame.

Eye AF makes it easier to get the most important part of your subject sharp, giving you the confidence to shoot wide-open. Credit: Angela Nicholson

Subject recognition

The AF systems are becoming increasingly sophisticated, and some can recognise the subject it’s supposed to focus on. It began with face detection and cameras spotting, highlighting and focusing on faces in the frame. Some Sony cameras, such as the A7 III, can recognise registered faces. The system allows you to register individual faces so that it prioritises them in a scene. This is useful for wedding photographers who need to make sure that the bride and groom are the centre of attention in all their images.

Face Detection has also evolved into Eye Detection and Eye AF, allowing you to target the most critical part of a subject. Sony has taken it one step further and enabled it to work in continuous focusing mode. Since then it has proved hugely beneficial to wedding and social photographers. It’s particularly helpful when you want to shoot with the aperture wide open and depth of field is very limited.

Animal Eye AF should make capturing images of our four-legged friends a bit easier. Credit: Angela Nicholson

New subjects

Some exciting developments are going on in the field of subject recognition as camera manufacturers are working on extending the range of objects that their cameras can detect. For example, Sony has recently rolled out firmware updates to the A7 III and A7R III (and updates are promised for the A9 and A6400) to enable these cameras to detect and focus on animals’ eyes. This is good news for pet and wildlife photographers.

Meanwhile, the AF system in Olympus’s recently announced OM-D E-M1X camera has an intelligent subject-detection mode. At the moment it has three modes – Motorsports, Airplanes and Trains – but more are promised, with people and animals seeming to be obvious next subjects.

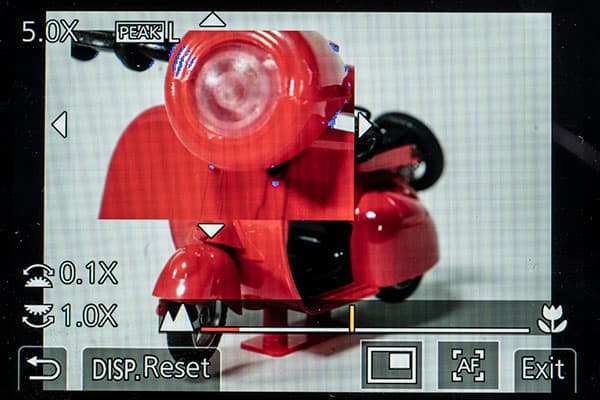

The ability to magnify the scene and use focus peaking makes it easier to focus manually. Credit: Angela Nicholson

Easy manual focusing

Occasionally, even with a top-notch AF system, you need (or want) to switch to manual focusing, and mirrorless cameras have a few neat tricks that can help here too. For example, like most DSLRs in Live View mode, mirrorless cameras usually magnify a selected area as soon as you move the lens focus ring. This makes it much easier to focus precisely. Unlike an SLR, however, a mirrorless camera can show the magnified view in the viewfinder or screen. Similarly, when focus peaking is activated, the display is visible in the viewfinder or on the screen. That’s useful because there are times, for instance in strong sunlight, when it’s easier or feels more natural to use the viewfinder rather than the screen.

It’s also nice that you can switch smoothly, and often automatically, between using the viewfinder and the main screen to focus and compose images with a mirrorless camera. It’s much clunkier with a DSLR because you have to activate and deactivate the Live View system to flip the mirror in and out of position.

It doesn’t matter if you use the screen or the viewfinder to compose images with a mirrorless camera, it will perform in the same way and produce identical images. Credit: Angela Nicholson

Fast and clever

Although the first camera to kickstart the move to shooting video on small stills cameras may have been a DSLR (the Canon EOS 5D Mark II), mirrorless cameras have picked up the ball and run with it. Cameras like the Panasonic Lumix GH5 and GH5S and Sony A7S Mark II are particularly good, offering the type of video specifications that were previously only found in large and hugely expensive cinema cameras.

This technology has also spawned new features that are useful for stills photographers. For example, the electronic shutters in many mirrorless cameras available today enable super-fast shutter speeds and high frame rates. The Panasonic Lumix G9, for example, can shoot at up to 1/32,000sec and 20fps (frames per second) at full resolution and with continuous AF. What’s more, it can do it silently, which means it’s useful in all sorts of situations that would normally be off-limits to photographers such as capturing the mid-performance leap of a ballet dancer, the service in a tennis match and the teeing-off at a golf tournament.

It’s all the same

As I’ve touched on already, another nice feature of mirrorless cameras is that their performance stays the same whether you’re shooting using the viewfinder or the screen. Digital SLRs, however, have separate AF, metering and white balance systems for use in Live View and reflex mode. As a result, if you switch from composing images in the viewfinder to using the screen, the exposure, colour and focusing can all change. And with the autofocusing, the focus point selection options change along with the system’s performance, all of which means you can’t swap seamlessly between shooting with the viewfinder and the screen like you can with a mirrorless camera.