There’s more to close-up and macro than plants, liquid art and bugs, says Tracy Calder. Top alternative macro photographers share their favourite subjects they find in everyday objects and the constant inspiration they find in bottles, dumpsters, rock formations and more…

Alternative Macro Subjects

Jennifer McKinnon

Photographic artist Jennifer McKinnon spends much of the year searching the streets in and around Atlanta for dumpsters. These unsightly waste containers can be found lurking behind shopping malls, sitting on construction sites and blocking people’s driveways. At first, she was attracted to them due to their unusual (and aesthetically pleasing) markings – a result of natural and unnatural weathering – but over time she came to realise that her images could be used to highlight the impact that waste and consumption has on the natural world.

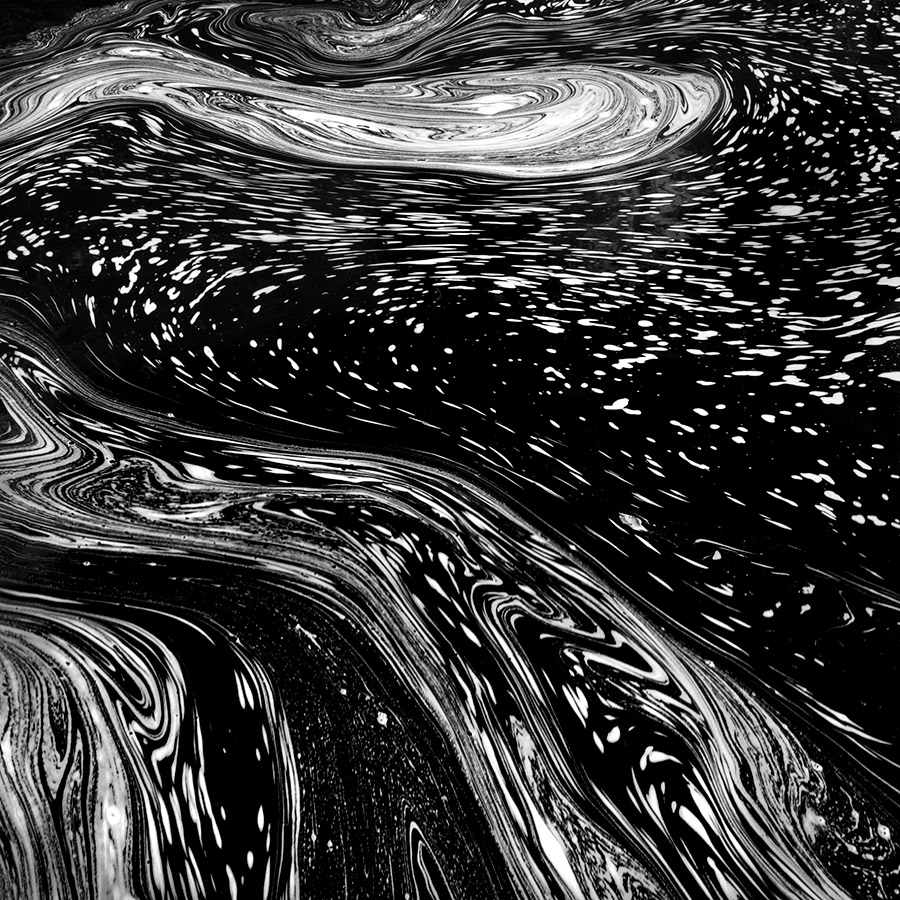

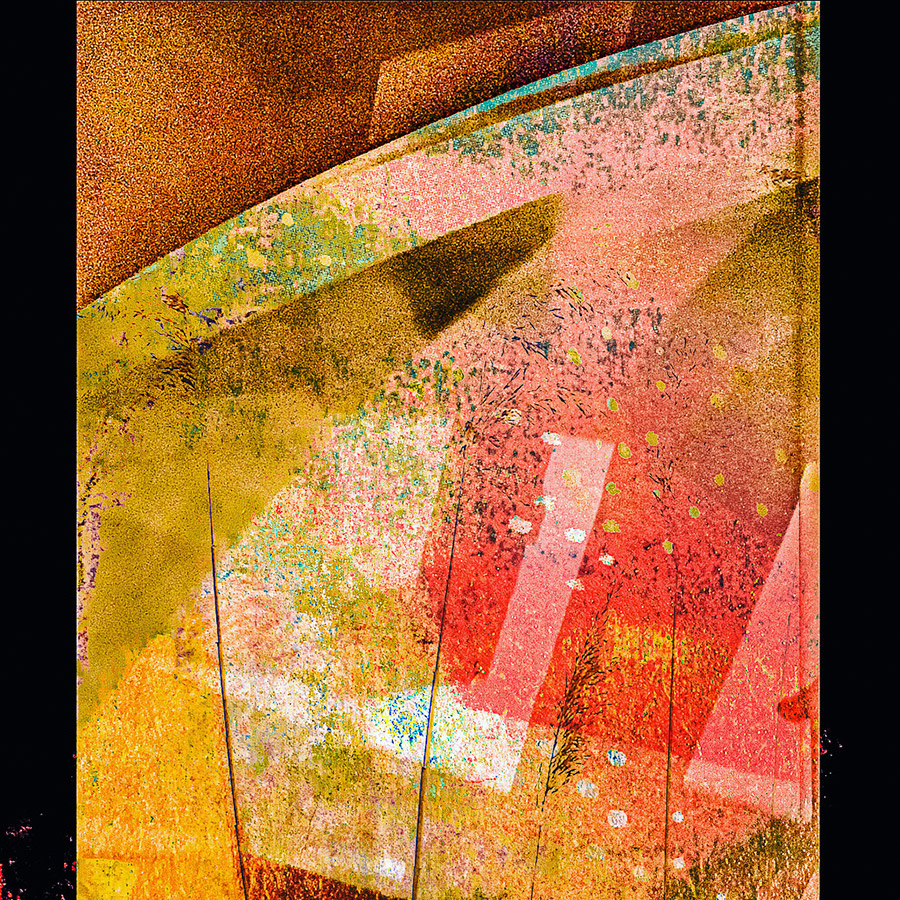

Her early ‘dumpster abstracts’ have instant graphic appeal: bands of colour sweep across the frame giving them the air of contemporary paintings. But in recent months she has been focusing more on digital composites – layering multiple abstracts in one image. ‘Think collage, but created using Photoshop,’ she explains.

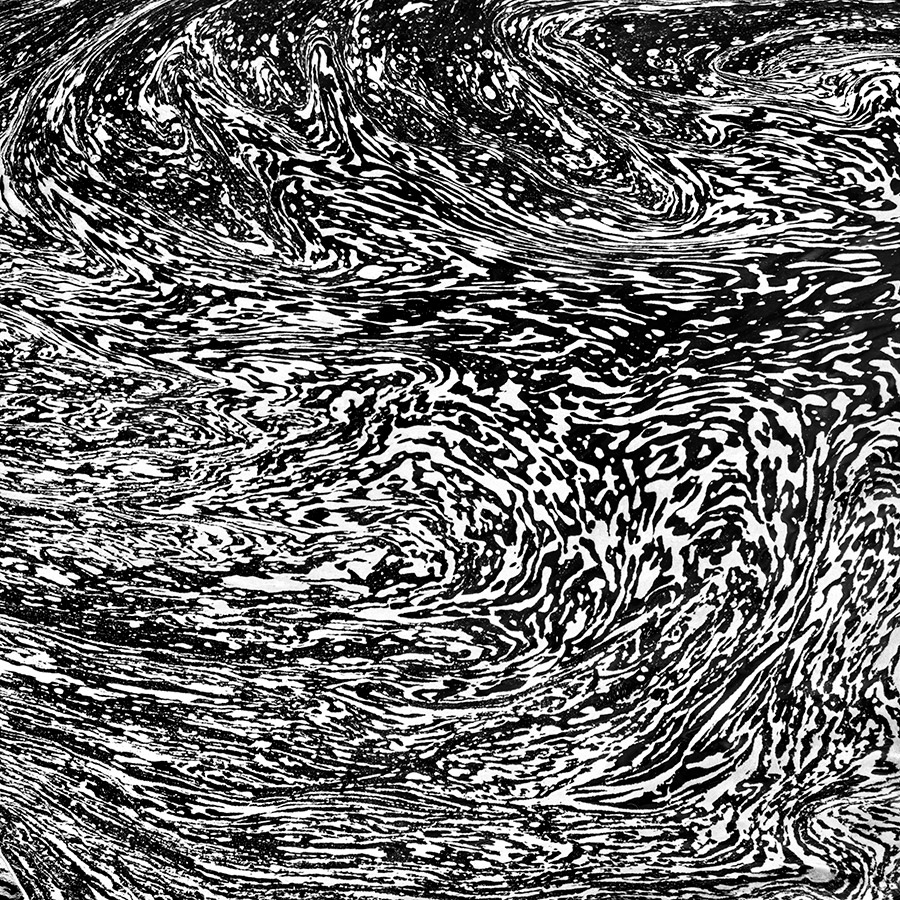

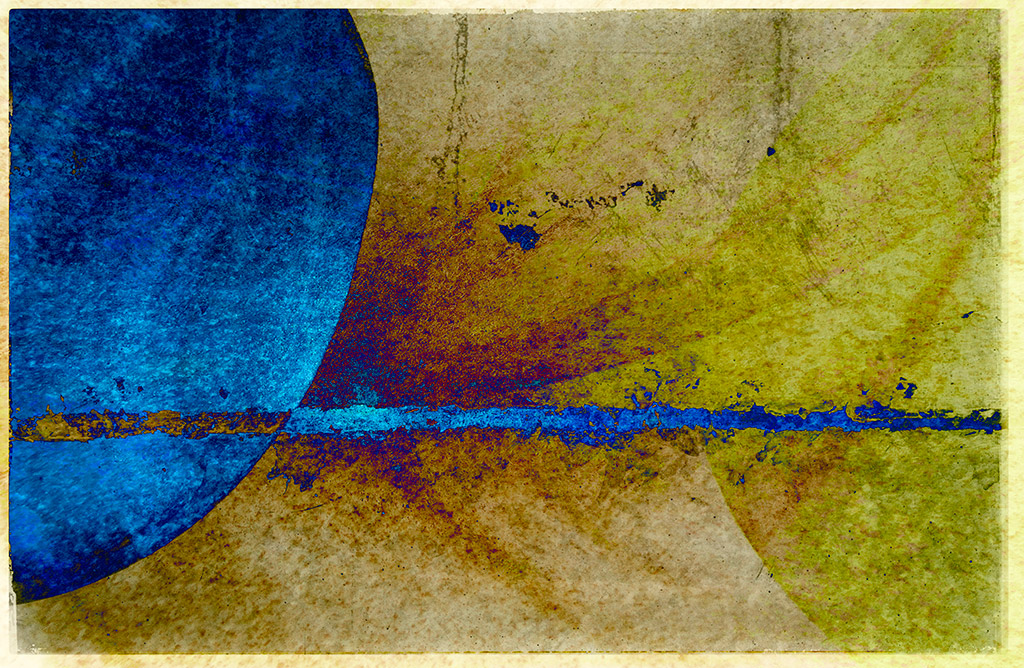

Urban Beach Day – 6.30am. Jennifer’s early ‘dumpster abstracts’ have instant graphic appeal. Olympus OM-D E-M5 II, 60mm Macro, 1/160sec at f/7.10, ISO 640. © Jennifer McKinnon

For the series Uncontained Consumption, for example, Jennifer layered ‘bits and pieces’ of dumpster walls to create composites that resemble waves, raging seas and vast sandy beaches. ‘Grease stains dissolve into beautiful ocean blue hues; grime found along the bottom of a dumpster is transformed into sandy shores; paint splatter is converted into white sea foam,’ she reveals. By taking details and combining them to create unique oceanscapes, she aims to mimic the process by which floating garbage patches and underwater landfills are formed.

The results are both striking and disturbing: ‘Beach Bum’, for example, is made up of ten abstract images and represents a common form of debris that’s found during coastal clean-ups: cigarette butts. It has a tactile quality: the ‘sand’ looks pitted with scorch marks and the ‘sky’ appears to be bubbling due to the blistering paint.

Ditch the labels

Jennifer clearly approaches her subjects with a beginner’s mind – a sense of openness and curiosity that enables her to go beyond the labels that we might normally associate with dumpsters. Most of us walk past these containers and, if we notice them at all, it triggers an internal dialogue that goes something like this, ‘It’s a dumpster, look at all that rubbish, that’s ugly, maybe I should hire one of these when I clear out the loft.’

When we look at an object like this, we’re not truly seeing it. What we’re doing is looking at it through a filter of judgements, preconceptions, labels and preferences. Of course, this wasn’t the case at the very beginning – when we were babies, for example, we would have explored the world by putting things into our mouths, experimenting with textures, shapes and tastes. At this stage we would’ve had no labels for objects, and no definitive knowledge of what they were used for. A spoon, for example, might have just felt cold to the touch and have been used as an instrument for hitting something with.

Abloom No.14. Bands of colour sweep across the frame, giving Jennifer’s abstracts the feeling of paintings. (Three images combined in Photoshop). Olympus OM-D E-M5 II (image one: 150mm, ISO 640, 1/60sec at f/8, image two: 60mm Macro, ISO 400, 1/800sec at f/5.6, image three: 60mm Macro, 1/320sec at f/7.1, ISO 640. © Jennifer McKinnon

As we grow older, we label and categorise objects around us – it’s our way of making sense of the world. But when we attach labels to things, we often attach judgements too: this object is ugly/beautiful, this one has great/no value, this one is going to be boring/interesting to photograph. Making judgements might help us to make decisions and move on quickly, but it does have its downsides.

Firstly, we close ourselves off to new opportunities: we see a dumpster and label it as ‘unsightly’, ‘functional’ or ‘unphotogenic’. In contrast, when we approach an everyday object with a ‘beginner’s mind’ and a sense of curiosity the creative possibilities are endless. ‘In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s, there are few,’ wrote Zen master Shunryu Suzuki.

Rachel McNulty

Embrace surprise

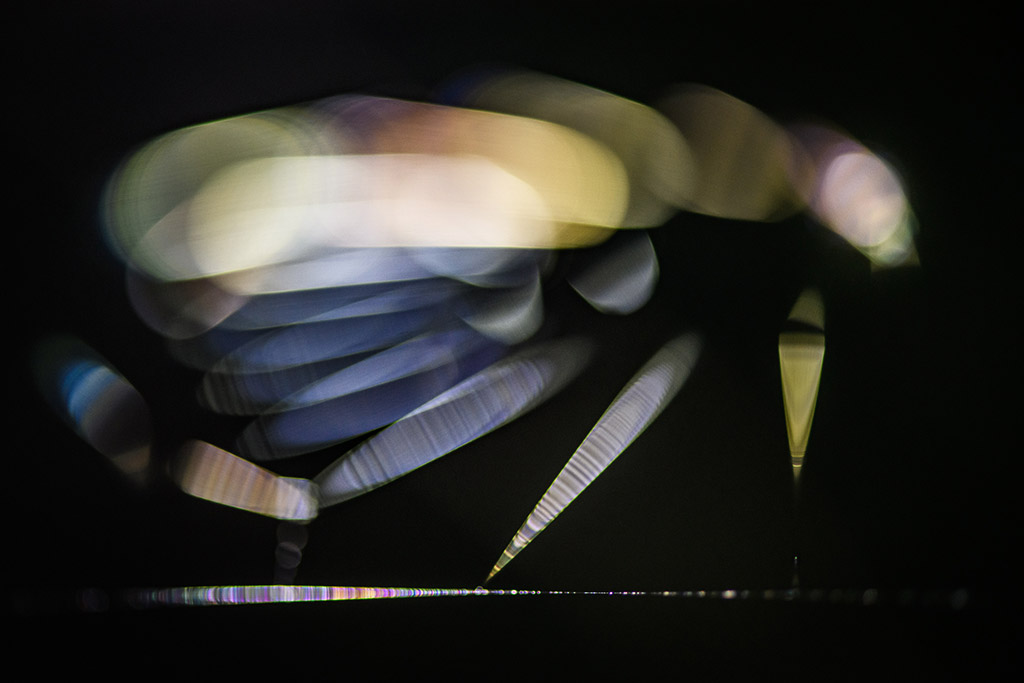

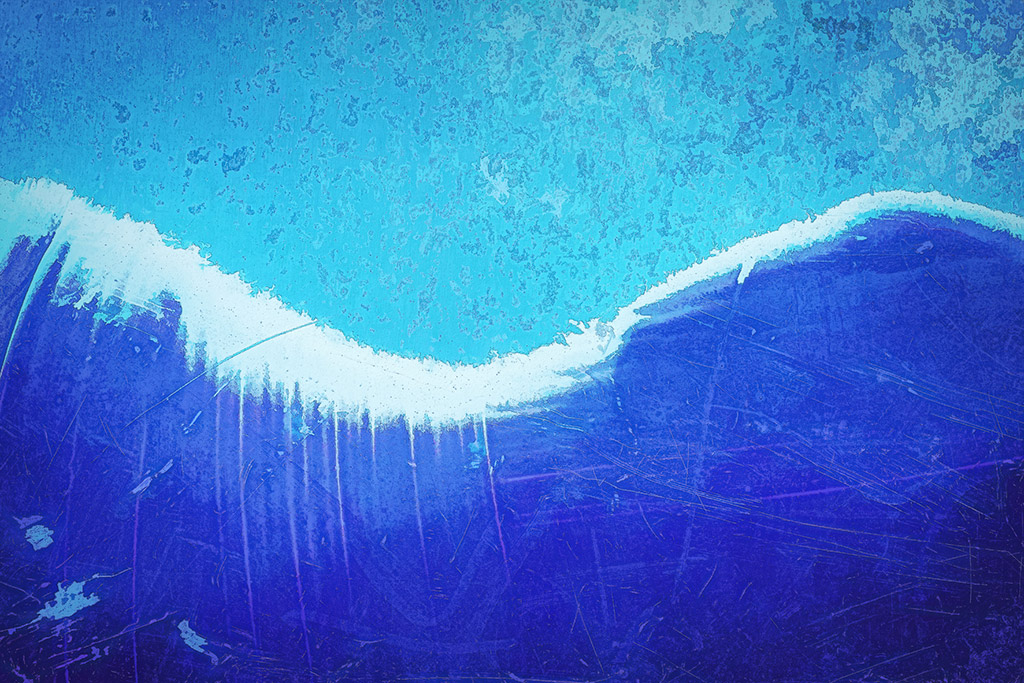

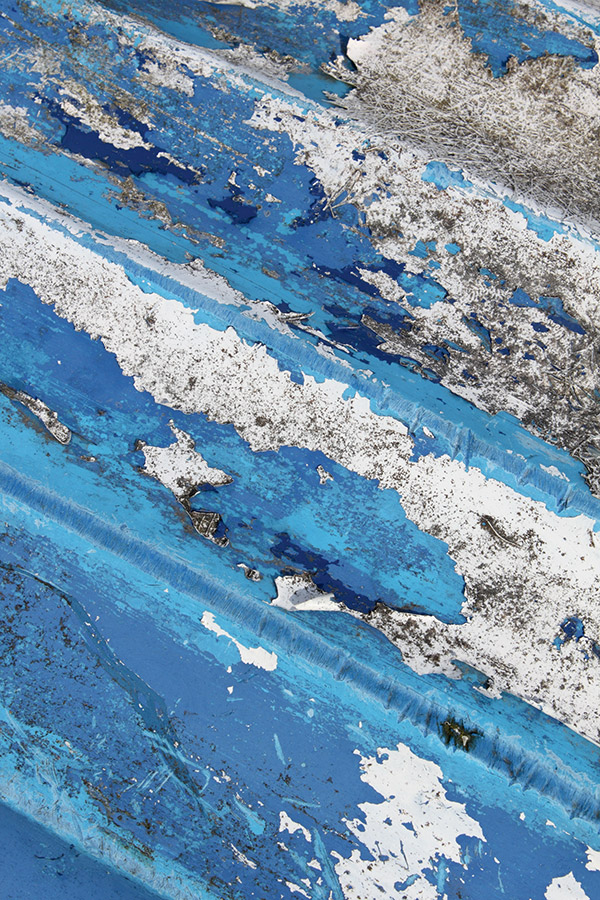

Another photographer who has managed to hold onto a childlike sense of curiosity is Rachel McNulty. At the start of the first UK lockdown in 2020, Rachel embarked on a home-based project to create abstract ‘seascapes’ using colourful glass bottles, a macro lens and daylight. The dining room table became her studio and the sunlight entering the room enhanced the colours and created incredible reflections inside the bottles.

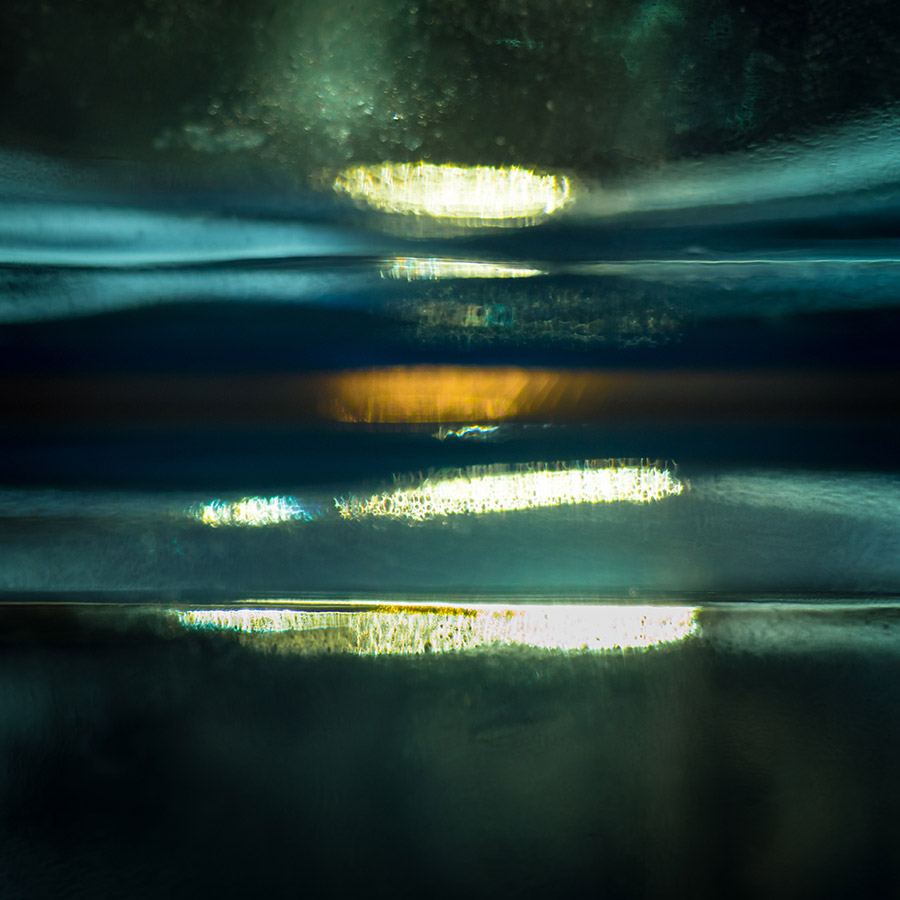

‘When I looked through the viewfinder, I suddenly saw waves crashing on a beach, storm clouds out at sea and dramatic sunsets,’ she recalls. ‘No two images will ever be the same: the light changes, the position of the bottle moves and the reflections shift, just like a real seascape constantly alters.’ Rachel isolates small sections of the bottles and uses a foil reflector to bounce extra light where it’s needed.

Stormy Skies. Details in a glass bottle give the impression of a dramatic sky above a calm blue sea Olympus E-M1 Mk II, 60mm f/2.8, 1/15sec at f/2.8, ISO 400. © Rachel McNulty

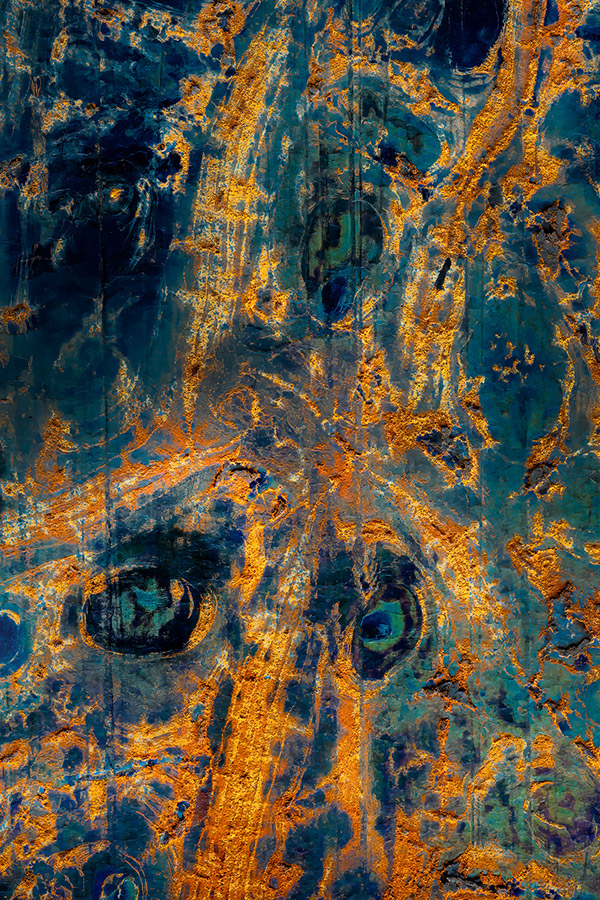

Many of Rachel’s seascapes (and landscapes) are created using gin bottles – as such, the colours in them vary from olive greens to candy pinks and electric blues. Together they look dreamy, as though they’re a visual representation of that delicious state between sleep and full consciousness. Swirls of light dart across the frame, encouraging us to imagine sunlight breaking through the clouds and dancing on the water below.

‘They are such fun to do,’ says Rachel. ‘They really take me off to the coast in my head when I’m creating them.’ Her pleasure, and her willingness to embrace surprises, shows in her work. In 2021 her image ‘Waves Crashing’ (featuring a section of a blue gin bottle) won the Manmade category of Close-up Photographer of the Year.

Golden Sunset. A Cointreau bottle placed above a Bombay Sapphire Gin bottle created a golden sky over a turquoise sea Olympus E-M1 Mk II,

60mm f/2.8, 1/125sec at f/2.8, ISO 200. © Rachel McNulty

Stay open and curious

Like Jennifer, Rachel seems to adopt a beginner’s mind when she embarks on a photography session. There’s a sense openness, receptivity and delight. It’s a mindful approach that results in fresh insight and clear seeing. ‘The mindful photographer combines an insatiable curiosity about the world with a radically open heart and mind,’ says Sophie Howarth in her brilliant book The Mindful Photographer.

It’s a balance that Rachel has struck perfectly. Both photographers champion everyday objects, and in doing so they ask us to reassess the way we see them too. Instead of empty gin bottles waiting to be recycled we are encouraged to see colours and shapes interacting and influencing one another. We are invited to marvel at something extraordinary found in the ordinary.

Similarly, when we look at Jennifer’s dumpster pictures, we see a freshness that comes from remaining open and curious. The New Economics Foundation (a think-tank promoting social, economic and environmental justice) recommends paying mindful attention to our surroundings as a way of boosting well-being. ‘Take notice. Be curious. Catch sight of the beautiful. Remark on the unusual,’ they urge. Both Jennifer and Rachel embody this mantra.

Reflection. Reflections from two turquoise blue gin bottles placed one above the other Olympus E-M1 Mk II, 12-40mm f/2.8, 1/1000sec at f/3.2, ISO 200. © Rachel McNulty

David Southern

Let your imagination go wild

David Southern is a photographer who definitely knows how to ‘be curious’ and ‘catch sight of the beautiful’. His book, Shoreline, is a celebration of quiet, intimate landscapes captured along the Northumbrian coast. ‘When I first moved to the region it was the spectacular castles and vast sandy bays that proved to be irresistible attractions,’ he reveals.

But before long David found himself inescapably drawn to the area’s rich geology, eventually widening his photographic net to include seaweed, sand and shells. ‘The geology of the Northumbrian coastline is made up of a great many types of rock including dolerite, sandstone and shales,’ he explains. ‘It has taken many years and thousands of tidal cycles to sculpt these rock forms. However, their appearance can change almost on a daily basis making each visit to a location a voyage of discovery.’

Mercury. When he first moved to the coast David was attracted to the grand vistas, but he soon found himself drawn to the geology. Canon EOS 5D Mk IV, 50mm, 1/8sec at f/16, ISO 100. © David Southern

David can spend hours ‘considering and contemplating’ a small patch of shoreline – an experience he likens to meditation. ‘Over the course of such explorations the subtleties of light, shade and water flow reveal contours and textures that may lend themselves to a compelling image,’ he explains. All the images in Shoreline were created along a 40-mile stretch of coastline – an amazing achievement when you consider the variety and diversity on display.

Layers in a rock become waves on a choppy sea, grooves appear to be canyons, a well-positioned hole becomes the eye of a sleepy dinosaur. For the most part, there is no sense of scale, so our imagination is free to roam wild.

‘With each visit it became clear that to extend the boundaries for finding new discoveries I would have to let my imagination off the leash and not limit myself to just an attractive pattern or shape etched in rock,’ says David.

Skelton. All of David’s intimate landscapes were captured along a 40-mile stretch of coastline

Canon PowerShot G1 X Mk III, 15-45mm, 1/250sec at f/6.3, ISO 100. © David Southern

Notice the overlooked

It’s hard to push past the obvious and look for something deeper, fresher and more meaningful but, as David illustrates, when we approach our surroundings with an air of curiosity, we are often richly rewarded. The sense of wonder that he feels for this stretch of coast is palpable, and the relationship he has with the landscape has led to a sense of enormous well-being.

David notices the overlooked, he rejoices in detail and, thankfully, he has the creative and technical ability to share what he discovers with other people. ‘See the world with fresh eyes, one small piece at a time,’ urges Howarth. It’s something David does brilliantly.

These photographers notice the world in a way that most others don’t. They marvel at the shapes, colours and textures of everyday objects and overlooked scenes, they approach the commonplace with an air of delight and childlike curiosity, and they ‘see’ what’s in front of them with their hearts as well as their eyes and minds. In the words of Andy Karr and Michael Wood, authors of The Practice of Contemplative Photography, ‘This ordinary, workaday world is rich and good.’

Wave. David can spend hours contemplating a small patch of shoreline. Layers of rock can become waves on the sea Canon EOS 6D Mark II, 17-40mm, 0.8sec at f/20, ISO 320. © David Southern

Rob Blanken

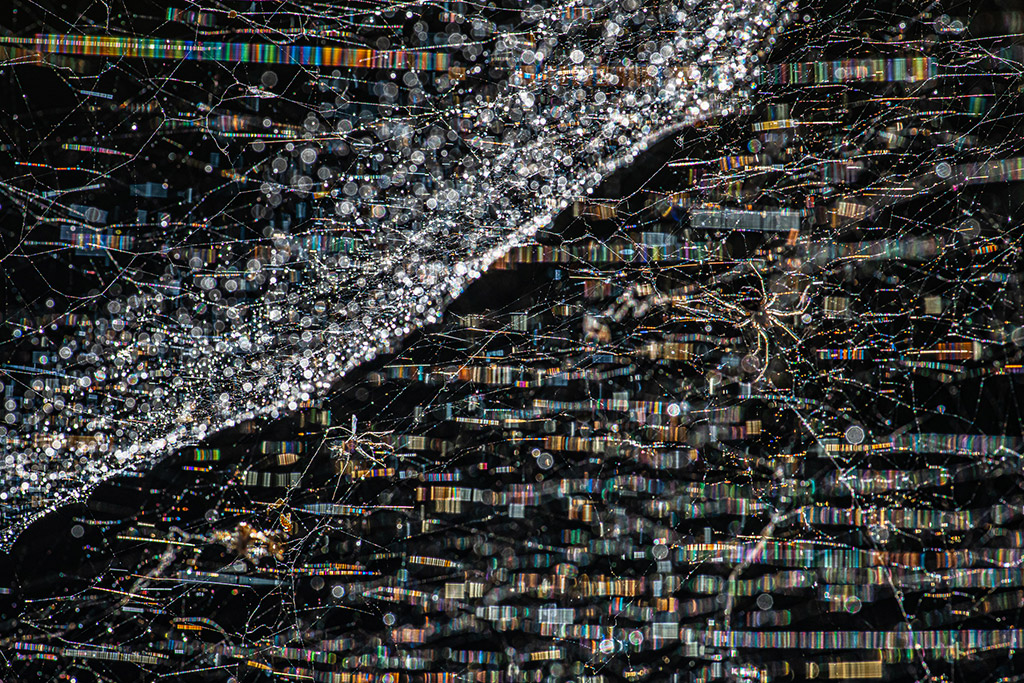

Having recently retired from his career as a dermatologist, Rob Blanken is delighted to be able to spend more time pursuing his passion for nature photography – in particular birds, insects and abstract compositions. Rob strives to capture ‘ordinary’ subjects in a fresh and unusual way, while also evoking emotions and communicating stories via his photography. He lives in the north of the Netherlands with his wife and two border terriers.

See differently

Training your eyes to see ordinary subjects in new, interesting ways takes time and patience. For Rob Blanken, the process begins by looking at the work of other nature photographers (especially the ‘real toppers’), which gives him an extensive frame of reference. Doing so also helps him to identify, ‘what has not been done yet’, which sparks ideas. Outside photography, Rob admires the work of painters JMW Turner (‘especially his use of colour’), Mark Rothko and Egon Schiele.

While his style is very much his own, he admits there’s much in the world that he finds beautiful and fascinating, and subconsciously it must influence his work. But what, I wonder, does a former career as a dermatologist bring to the mix? ‘Dermatology is a profession that requires careful attention,’ he says. ‘Small differences can have important consequences. It’s the same with photography. I know quite a few dermatologists who paint or take pictures!’

In 2018 Rob realised that he was taking more and more ‘abstract’ pictures. ‘I was capturing ordinary subjects in unusual, often unrecognisable ways,’ he recalls. ‘Gradually the level of abstraction increased.’ By then he’d taught himself to think carefully before releasing the shutter. When Rob comes across a promising scene he stops, asks himself what feelings it evokes in him and then tries to capture this in the picture.

‘Emotion strongly influences the design of my photographs,’ he admits. ‘I’m looking for a story that can be interpreted in multiple ways. It helps that I have a lot of imagination and a romantic side!’ Sometimes Rob has an idea of what he wants in his mind’s eye, but often it’s a case of spending time with a subject and letting everything ‘sink in’. Working out how to tackle a subject comes naturally and quickly to him, but fine-tuning a picture is different. ‘I will try out everything in terms of composition, lighting etc,’ he says. ‘If I am shooting with a group, I invariably take the most pictures!’

Long projects

Rob finds working on long-term projects (as opposed to shooting standalone pictures) especially rewarding, as he believes it gives your photography greater depth. ‘Working on long projects forces you to really pay attention to your subject and approach it differently,’ he says. ‘If you do this, your photography will become technically better and, crucially, your work will become more creative and original.’ For around five years, Rob has been primarily photographing spiders, and has seen the quality and originality of his work go up as a result. ‘Paying a lot of attention to a limited number of subjects will definitely make you a better photographer,’ he concludes. Rob has another great piece of advice when it comes to improving your work. ‘Take a really critical look at your pictures and evaluate your efforts with someone who understands the work and dares to give his/her opinion honestly.’

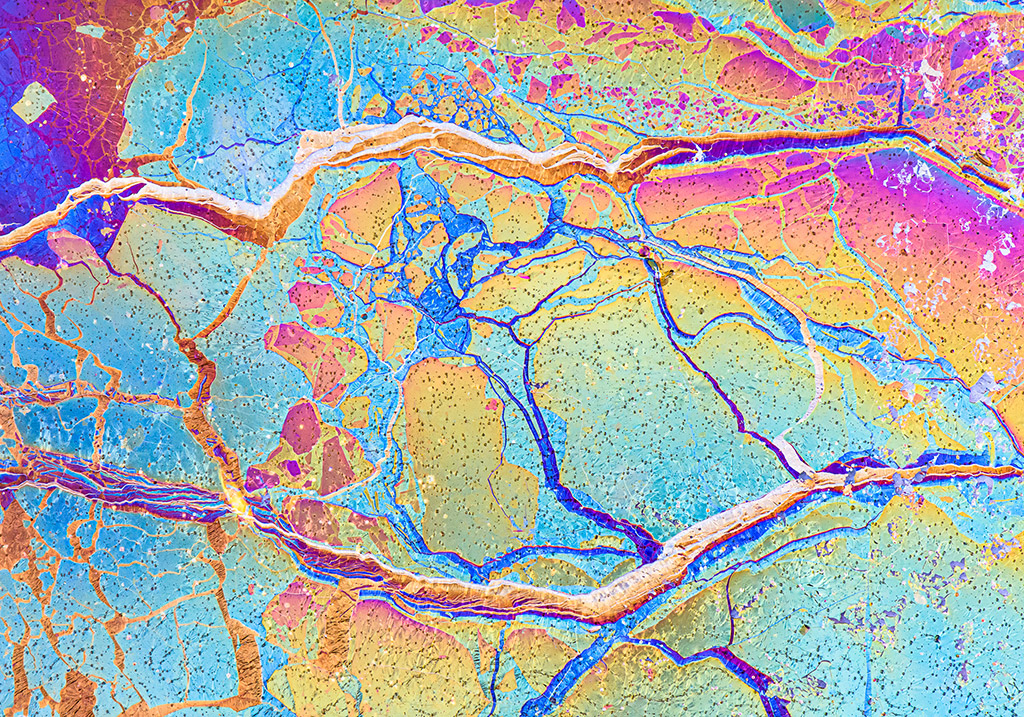

Crystals formed by combining different acids, taken using polarising filters. Image credit: Rob Blanken

Rob clearly enjoys the creative challenges presented by close-up and macro photography. ‘If something goes well, I get into a kind of flow,’ he reveals. ‘This applies to the entire creative process, which consists of developing the idea, thinking about the meaning of the image, designing the photo, the technique needed to capture it and the post-processing. You have to get the creative part and the technical part of your brain to work together and that can be very relaxing!’

Rob uses two Nikon bodies: a D500 and D850. He shares a lot of equipment with his wife who is also a nature photographer. ‘We travel a lot together, dragging all sorts of things along with us including tripods, clamps, coloured pieces of cardboard, filters, flashes and lights,’ he says. ‘Mostly I use a Nikon 105mm macro lens or a Sigma 180mm f/2.8 macro.’ For higher magnifications Rob uses a Laowa 2.5x5x Ultra Macro lens.

Rob’s alternative macro top tips

- Study the work of other photographers, and artists who work outside the medium. Try to identify gaps in the coverage and be willing to experiment.

- Start a long-term project, it will improve your technique and encourage you to be more creative and original in your work.

- Ask someone you trust, and who understands your work, to look through your portfolio and offer constructive feedback.

Hal Gage

Hal Gage studied painting and photography at university but after graduating he spent a few years earning a living as as a musician. His passion for photography took centre stage in the 1980s when he began working as a commercial photographer and graphic designer. Hal’s art has been exhibited widely in Alaska, the US, Europe, Russia and the far East, and examples can be found in collections at a number of prestigious museums.

Try rearranging

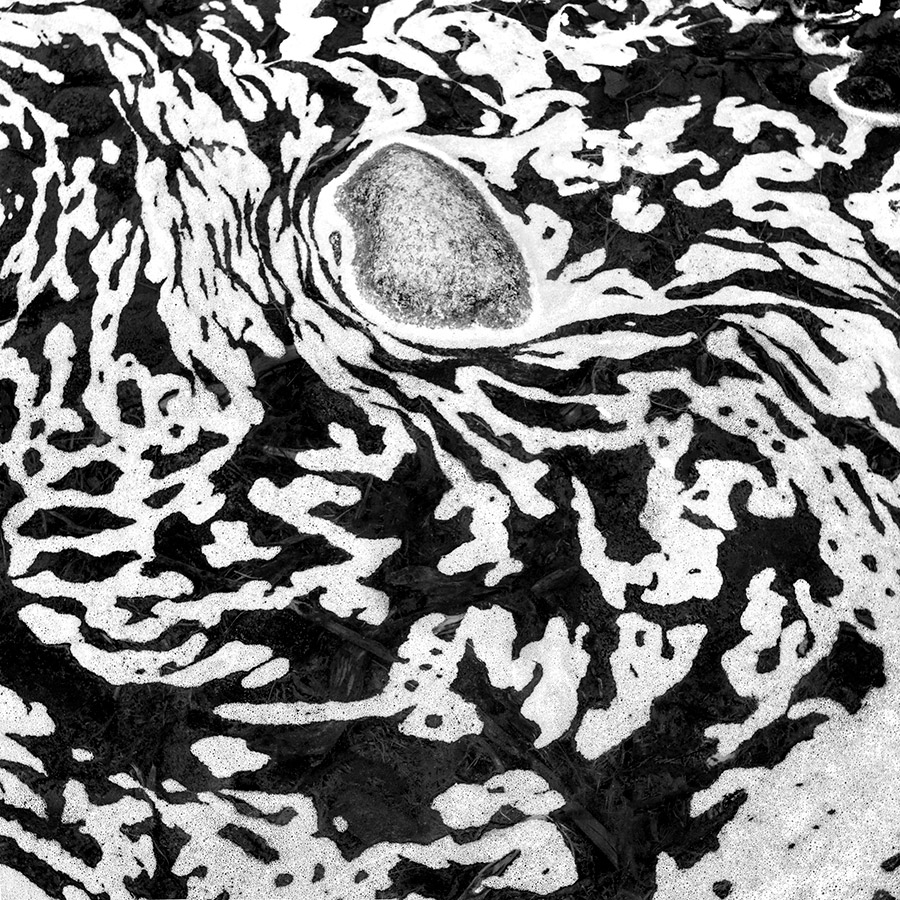

When Hal Gage was out photographing in the Alaskan wilderness, he came across a boggy lake shore. ‘The wind had worked up the surface of the organic rich waters and produced a frothy foam-like material,’ he recalls. ‘The breeze was moving and shaping this material into wild patterns. I became obsessed with them and must have spent three or four hours working them.’

Once Hal had spotted this natural phenomenon, he began to notice it in other situations. ‘Now every time I see it, it shows me something new and different. It’s magical,’ he exclaims. At first, the watery scenes Hal discovered felt quite chaotic. ‘It takes time to untangle (figuratively) the patterns and arrange the frame,’ he says.

‘Top, middle, sides and bottom: everything has to create some kind of movement (again, figuratively speaking) to keep the eye engaged.’ This ‘untangling’ can take hours – but once Hal has formed an arrangement in his mind’s eye, he then finds the execution of the idea quite easy. Hal has a background in painting and music, and he is a graphic designer by trade, so I’m curious to know if these skills and passions feed into his work. ‘I think so,’ he says. ‘I really can’t say what others see, but I am conscious of my 2D design training.

I strive to arrange lines, shapes, colours and tones in a pleasing 2D arrangement in my viewfinder. I do like colour, but pure shape and line are what really excite me. Stripping away colour helps to simplify something and get to its essence.’ Painting and drawing have taught Hal how to work within a frame, achieving balance while communicating ideas using colour and tone. He jokes that he’s a formalist at heart and composes, ‘everything to within an inch of its life’, but there is an unmistakable vibrancy and energy to the work as well as a Zen-like quality. ‘I’m glad you see that,’ he remarks. ‘I have always felt that the natural world has its own voice and it’s my mission to listen and hear it. It’s more of a “quiet drama” – not loud and brash, but subtle and nuanced.’

Find patterns in alternative macro subjects

The Pond Scum series reflects Hal’s love of patterns. ‘I see them everywhere,’ he laughs. ‘In a landscape, in a cityscape, in a piece of wood, in a random arrangement of things!’ Humans are hardwired to recognise patterns, and Hal is particularly good at spotting them. ‘As a lover of well-crafted books (and a book designer myself) I have always loved marbled paper end sheets,’ he explains. ‘Paper marbling is an ancient craft. I’ve often thought that the ancient practitioners must have been influenced by things that they saw in nature, like the surface foams on water and froth on the shores.’

It’s a wonderful idea and demonstrates Hal’s acute observational skills. He also looks for patterns while going through his image catalogue. When something presents itself, he begins to flesh it out and, ‘if it makes it beyond the sketchbook stage’ to turn it into a project. His projects can take decades to complete. ‘The point of a project is to take time to stop, look and listen to your subject,’ he urges. ‘I see everything on Earth (including Earth itself) as having a spirit, an energy at its core. If you listen patiently, on an emotional level, it will tell you its story.’

Hal uses a Sony A7R IV with a variety of lenses including a 90mm macro. He often shoots long exposures, which makes a tripod essential. Prior to 2008 Hal mostly shot film using a 6x6cm Hasselblad and has spent a fair amount of time digitising his archive of black & white negatives. ‘I don’t know if I will ever finish, but the exploration of my past work has been a wonderful experience,’ he admits.

Hal’s alternative macro top tips

- When you work in a formal way it can be quite exhausting, so it’s important to introduce an element of playfulness now and again. To bring an element of chance into the equation, I like photographing with my vintage Diana camera with all its lens flaws and light leaks. You never really know what’s going to come out of it!

- Another way to loosen up is to photograph public parties. I use a flash and roam around making images, usually without looking through the viewfinder (or at the LCD monitor). I compose by ‘guess or by-gosh’. These images are as much about editing and happy accidents as they are about capturing the moment.’

Ann Newman

For Ann Newman, abstract photography is a way to connect to her feelings and slow down. The symbolism she encounters in these intimate scenes also serve as prompts for her writing. ‘With an appreciation for the present moment, abstracts open our perspective, encourage creativity, foster empathy and buoy optimism,’ she suggests.

If you’re on a road trip with Ann Newman you’ll soon know if she’s found something worth photographing, because she’ll yell, ‘Stop the car!’ in your ear. ‘I’m attracted to something right off, and I’ve learned the hard way that you have to shoot the attraction as soon as you see it,’ she enthuses. ‘If you fail to act fast, the light can change, your creativity will fade, you’ll get hungry (or even hangry).’ Before she gets her camera and tripod out, Ann often shoots a few frames on her mobile phone to help her understand what kind of composition she is looking for. Next, it’s a case of slowing down.

‘I ask myself, why am I engaging with this? What is attracting my eye? What does this remind me of? Why should someone else care about this? Could I make a collection from this subject?’ she explains. The last question encourages Ann to shoot a variety of perspectives before moving on. ‘I might not use them, but it’s better to get them than fixate later on having missed them.’

Slow down

Ann believes that abstract photography – where the subject is often unrecognisable or shown in a fresh way – fires up the imagination and changes how we view the world. ‘As a bonus, this style of photography encourages us to slow down,’ she suggests. ‘Whether you are the photographer or the viewer engaging with the art, you are practising mindfulness when you explore abstracts.’ In order to ‘see’ a subject in a new way you need to be curious and also open-minded.

‘Once you slow down, you’ll naturally start to see things that you would otherwise pass,’ assures Ann. ‘If you open your mind to the possibilities, there is no way to run out of imagery.’ In order to train her eye to spot unusual objects (or objects to photograph in an unusual way), Ann pretends she is with a well-known abstract photographer and has been challenged to make art in the space that surrounds her. As a someone who regularly passes through vast desert landscapes, she has to really study the land to find something engaging. ‘It isn’t easy,’ she admits, ‘but if you continue to practise in this way you will end up in a place that is spilling over with amazing possibilities.’

Ann urges us to be aware of that inner voice that tells us there is nothing to photograph. ‘Hogwash!’ she laughs. ‘Get closer. If you’re out in nature, even the humblest plant has details that will amaze you. If you’re stuck inside, look for shapes, shadows and colours.’ When people ask her if she sets out with an image in mind or just responds to what she finds, Ann explains it can often be both. If she has an idea to execute, she will work on that first, while remaining open to new possibilities.

‘Sometimes I will be guided to something even better, and those images feel like a gift,’ she explains. ‘Most of the time I am looking for an ordinary object that wants its story to be known.’ Once she has found a suitable subject and slowed down enough to give it her full attention, Ann finds that her thoughts quieten and shift away from day-to-day concerns. ‘That’s when you access your inner world,’ she says. ‘As you brainstorm, your intuition leaps forth and offers ideas that might surprise you. As adults we don’t take time out to explore like this often. Abstract photography offers us a way to play.’

Ann uses a Sony A7R III and a 90mm lens for most of her close-up work but knows that if she doesn’t take her 70-200mm and 200-600mm with her she will ‘invariably see something that would’ve been perfect for them to handle’. Her close-up work is typically focus stacked, so a tripod is essential. Her post-processing is carried out in Lightroom and Photoshop and she has added Tony Kuyper’s luminosity mask add-in for Photoshop as well as Topaz Photo AI, Sharpen, DeNoise, and Studio to give her further options when it comes to enhancing her images.

Ann’s alternative macro top tips

- Look at the lives and influences of artists you admire and think about how their art changed over time. I like Monet, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Mell, Dixon and Swinnerton, among others.

- Read. Books about mythology have impacted both my abstract work and my writing. Humans love stories, because we are all heroes under some sort of pressure: we face conflict, we grow, and we overcome.

- Having started out as a writer, I love adding words to my images. When words and images come together, sometimes they are a love story, a comedy or a drama. I am exhilarated by the road they send me down.

Anette Holt

Anette Holt’s fascination with photography began as a child when she won a camera in a raffle and began taking snapshots with it. Since then, she has enjoyed capturing landscapes and wildlife, shooting black & white and, more recently, abstract photography. Based in the East Midlands, she has exhibited in the UK and in her native Germany and her artwork has been sold to collectors around the world.

Break the rules

Anette Holt enjoys breaking the rules of ‘traditional’ photography. Many of her abstract images are a result of double exposures, distortion, unusual viewpoints or placing details out of context. ‘I enjoy the unforeseeable outcomes and surprising results these techniques bear,’ she explains. ‘I also like the fact that each photo is so unique that it’s almost impossible to reproduce it, even for me!’ According to Anette, successful abstract images require a balance of colours, shapes and textures – three ingredients that she loves to play with.

‘I would probably describe myself an artist who happens to use a camera instead of a paintbrush to produce painterly pictures,’ she says. ‘I hope my abstract images inspire the viewer to look beyond reality as we know it.’ With her abstracts, Anette has no desire to present a realistic view of the world; instead, she aims to create a different reality by focusing on details or angles that are often overlooked. ‘Abstract photography is a way of expressing ideas and emotions, as well as discovering the unexpected,’ she enthuses.

Remaining playful is essential when it comes to abstracts, and Anette is not afraid to experiment. ‘It’s important to remain open to new approaches,’ she says. ‘The sources of my inspiration can be manmade or naturally occurring – either way I keep an open mind and play with different techniques. These can be close-ups, out-of-context details, unusual crops and perspectives, multiple exposures, composites, intentional camera movement, flipping, rotating, distorting, long exposures and shallow depth of field – the possibilities are endless!’

Trust your intuition

Naturally, there is a fair amount of trial and error involved, but Anette prefers to view ‘failures’ as a crucial part of the learning process. ‘There’s a lot to discover if we allow ourselves to deviate from the idea that a photograph has to be pin-sharp or we have to follow the rule of thirds,’ she assures. It comes as no surprise to learn that Anette draws inspiration from a variety of mediums including painters such as Klimt, Kandinsky, Klee and the Blauer Reiter (Blue Rider) movement, as well as sculptors Giacometti, Moore and Saint Phalle.

When Anette is creating an abstract, she prefers to be guided by intuition rather than a specific plan. ‘I don’t make notes and it can be difficult to remember the steps I took that led to a certain result,’ she says. ‘For me, this is part of the fun and makes each image truly unique!’ Ultimately, Anette wants to give the viewer room ‘for their own interpretations and projections’ rather than steer them in any one direction. While the ‘real’ subject of the piece is unimportant to Anette, she is often asked, ‘What is it?’ by people looking at the work.

‘To give you an example, “Summertime” consists of several layers of shadow lines on a wall, shot from different angles (I rotated the camera), overlaid with some close-ups of a rusty surface for texture and colours, superimposed with a photo of dry reeds.’ I see her point! Maybe it’s best to bring our own ‘reading’ to the piece rather than get lost in the details! Abstract photography brings Anette a great deal of pleasure, and it shows in her work.

‘I know that I can only be good at something if I enjoy it,’ she agrees. ‘While a representational approach to photography has its own fascinations, I enjoy the intuitive approach of abstract photography. I am fascinated by the possibilities and how my imagination gets stimulated when I am playing with creative techniques.’

Most of Anette’s photography is unplanned, and inspired by something that she comes across by accident. As such, she often uses her iPhone, relying on the Photosplit app for multiple exposures and the Snapseed app for post processing. When she’s heading out with the intention of taking pictures, she uses a Nikon D810 with either a 70-300mm or a 50mm lens.

Anette’s alternative macro top tips

- Art can be found anywhere if you look closely. A lot of nature can be considered art, but manmade materials are also very inspiring – particularly when you take parts out of context. It’s fascinating to see how materials alter and change as a result of natural processes – such as rust, for example.

- Don’t be shy of using the sliders in Lightroom! Changing the white balance alone can lead to great results, but it’s also worth trying out all the other sliders in all sorts of combinations. Playing can be fun!

- You don’t have to travel far to create striking abstract images. Mundane subjects such as a close-up of a reflection on a puddle, a crack in a wall, a piece of timber or flaking paint can be transformed into something interesting. You can also create landscapes and scenes by shooting images of everyday objects and combining them in layers.

5 tips for shooting everyday (but interesting) alternative macro subjects

Adopt a beginner’s mind

If we adopt a childlike curiosity, even the most commonplace objects and scenes reveal their photographic potential. Marvel at your subject’s colour, shape and texture, look at the way the light emphasises its form, consider the positive and negative space.

Embrace uncertainty

If we embrace uncertainty, we can find mystery and fascination in the familiar. Think like an explorer: go down a street you’ve never been down, open a drawer and photograph the first thing you see. In other words, welcome the unexpected.

Meditate on an object

Spend 20 minutes observing your subject – even if it appears static. Observe the way that light and shade reveal its contours and texture. Look with a sense of awe and astonishment. Don’t take any pictures to begin with, just observe.

Ask ‘what if?’

Take an everyday object and ask what would this look like if I took it apart and shot the components? What if this particular object had never been invented – what would I have used instead? What if I shot this object from above, inside, underneath?

Stop looking, start seeing

Most of the time, we see objects through a veil of judgements and preconceptions. However, if we take the time to observe and notice details, then we see with fresh eyes. The more we look, the more our ‘noticing’ muscles grow.

10 books that help you see

- Close-up and Macro Photography by Robert Thompson

- Conscious Creativity by Philippa Stanton

- Digital Macro & Close-up Photography (revised and expanded) by Ross Hoddinott

- The Little Book of Contemplative Photography: Seeing with Wonder, Respect, and Humility by Howard Zehr

- Mastering Macro Photography by David Taylor

- The Mindful Photographer by Sophie Howarth

- The Photographer’s Playbook by Jason Fulford and Gregory Halpern

- The Practice of Contemplative Photography: Seeing the World with Fresh Eyes by Andy Karr and Michael Wood

- Stop, Look, Breathe, Create by Wendy Ann Greenhalgh

- The Tao of Photography: Seeing Beyond Seeing by Philippe L Gross

Just getting started with macro photography? Check out our beginners guide to Macro Photography

Submit your best Macro photographs to our Amateur Photographer of the Year 2023 competition – the Macro round is now open! Click here to enter.

Related Reading:

Best macro lenses for mirrorless and DSLRs

How to get great autumn macro shots

Top 31 best close-up and macro photographs

30 ways to photograph a bouquet of flowers

Close-up tips from Two of a Kind CUPOTY Challenge winners