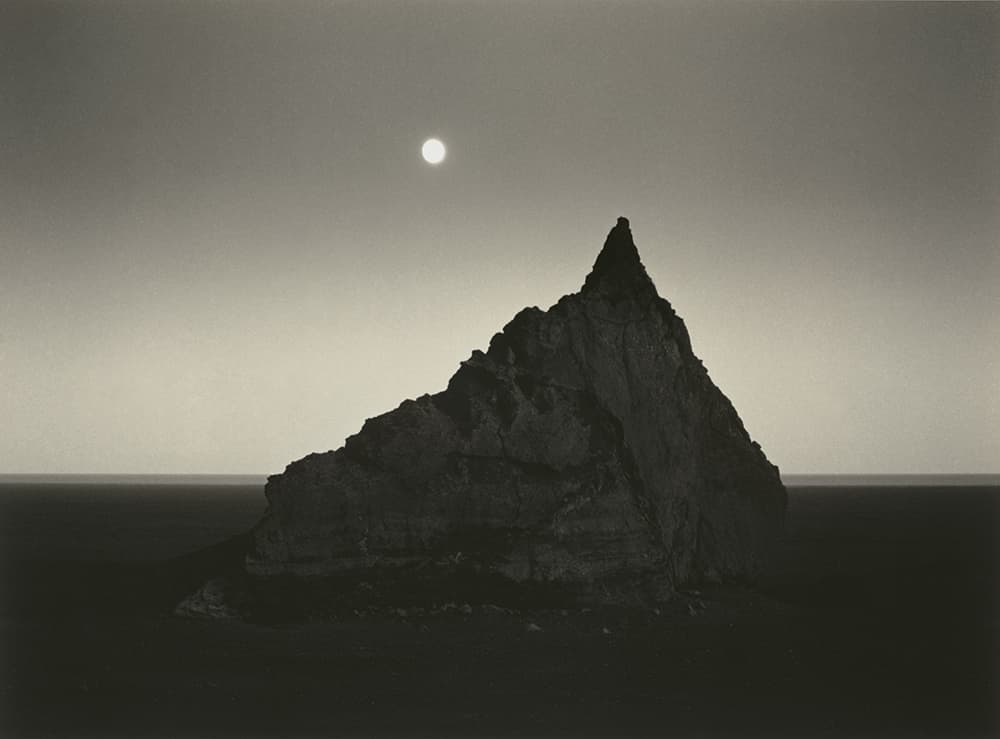

It was back in the 1970s that Tim Rudman first contemplated photographing Iceland. Tim had always liked the idea of exploring, and the cold region seemed to be a wonderful opportunity, a wonderful landscape and an inspirational country. However, it took until 2007 for this to become a reality. An upsurge in the popularity of photographing Iceland deterred Tim for many years, but he finally took the plunge and the end result is his new book Iceland: An Uneasy Calm, which takes its subtitle from the constant underlying threat of volcanic activity on the island.

Tim’s love affair with photography and printing dates back to the late 1960s, when he picked up a book by the late Sam Haskins. ‘From that moment I knew that’s what I had to do,’ he says. ‘I’d seen black & white photography used to document things for news, but I’d never seen it used in a sort of avant-garde way. It was a revelation to me – tilting the image dynamically, using huge grain, blowing out whites, blocking out blacks for positive and negative space – and I just thought it was fantastic. Within two weeks I’d found myself a community darkroom and was teaching myself to print.’ Other big early influences for Tim included Eugene Smith and Ansel Adams, but his printing skills are all self-taught via ‘practice and experimenting.’

The rollfilm route

Fast forward from Tim’s early 1960s’ inspirations to the present day and Opas Books is due to publish Iceland: An Uneasy Calm in October this year. The images for the book were all shot on Ilford Delta Professional 120 rollfilm, mainly ISO 100 or 400.

‘I use a Mamiya 645 camera because it’s a nice compromise between 35mm and 5x4in,’ says Tim. ‘I used to use 35mm, and I like its spontaneity, but the Mamiya 645 produces a bigger negative and it’s not as static as, say, a 5×4 camera. I shoot mostly on aperture priority, but sometimes I have to shoot on shutter-speed priority because of the lighting or the effect I want. I don’t have any other modus operandi other than to respond to what I see.’

Tim’s kitbag also includes a Manfrotto Neotec tripod and a range of yellow, orange and red neutral grad filters. ‘I use the orange filter quite a bit, but the red is a bit too heavy for my taste,’ he explains. ‘When I started I used prime lenses for everything, but then I got a couple of mid-range zooms. I used primes at the 35mm and 300mm end, and a couple of mid-zooms in between, because prime lenses left certain holes where you just couldn’t get what you wanted. I’ve got a 35mm fixed, a 300mm fixed, a 55-105mm and a 105-210mm lens.’

Finding locations

Tim initially went to Iceland with two groups led by US landscape photographer Bill Schwab. He admits he’s not generally comfortable in groups, but accepts that it’s a very good way of getting an introduction to somewhere he’s never been. After his group trips he went back to Iceland with friends or with his wife, who shoots in colour. One of these trips involved being stranded in a whiteout on Iceland’s highest road pass for eight hours before being rescued.

‘I found photographing Iceland initially very difficult, partly because I went with a group,’ explains Tim. ‘It was a great group, but I don’t like to stand around with others and all photograph the same thing – it’s not the way I like to work. For years I’d been photographing trees and lith printing them – then I went to Iceland and there wasn’t a tree to be seen. I found that quite hard for a few days and I just couldn’t get in touch with the landscape, which was a surprise. Then, suddenly, it started to speak to me and it was OK.’

Tim admits that his picture composition isn’t defined by rules. ‘It’s just instinctively what feels right,’ he says. ‘Sometimes it’s immediate and sometimes it’s elusive and you hunt around, change a little bit here and there, and work at it for ages – and then suddenly it’ll click or it doesn’t. You just have to try to find how it speaks to you and respond to it – I like to do that. Most of the places I go to now I try to go off-track and find somewhere that says “Iceland” to me, but isn’t necessarily where everybody goes. It doesn’t even have to be anywhere very scenic, but with the right light you can just pick up some detail, such as a pile of rocks on the side or something that has a feeling of Iceland about it. Often that’s not where people go to photograph, generally because it’s not one of the tourist spots.’

Over the eight years of shooting his project, Tim estimates that he went to Iceland about 10 times. ‘I spent anything from a week to the longest trip of six weeks,’ he says. ‘It’s never the same – the weather’s different, the clouds are different, the lighting’s different. It may be covered in snow, raining or just sunshine. I’ve been pretty much every month of the year except August and November/December. I’ve been there for the longest day and on the shorter days when, in the north, you’re getting four hours of daylight. That’s quite nice, but you don’t have a lot of time to shoot. In summer, at the end of June, you can shoot all night as it never gets dark. It’s a sort of soft twilight all night long.’

Tim’s early images of Iceland were exhibited in Sydney, Melbourne and Ballarat, Australia, in 2010, not long after the eruption of the volcano Eyjafjallajökull, which caused widespread disruption to air traffic around the world. It was the curator of the Sydney exhibition who dreamt up the An Uneasy Calm strapline that has since

has been incorporated into the book’s title.

Darkroom equipment and printing

Tim’s darkroom set-up includes, ‘An old Leitz condenser enlarger and a couple of German diffusion-condenser enlargers’. He also deploys an F-Stop Timer, which he adopted after much encouragement from his friend, the late US printer Gene Nocon, who invented it. ‘It’s a much better way of printing, with such fine control and it’s reproducible at any size you want to print,’ says Tim. ‘I just think it’s a brilliant tool.’

Tim’s images for the Iceland book were developed using Ilford Ilfotec DD-X developer with some negatives being intensified in selenium. ‘The prints were exposed with a diffusion-condenser enlarger onto Ilford Multigrade Warmtone fibre-based paper,’ he explains. ‘I use the F-Stop Timer and a split-grade timer as well. Everything on this work was split-graded using two filters (a Gr.00 and a Gr.5). This gives you all sorts of advantages when you get the hang of using it. It’s not lith – it’s dual-toned.’

Tim continues: ‘The use of split-grade printing helps to ensure that initially both contrast and time exposure accurately match the negative and paper, thus ensuring that subsequent printing manipulation is all about interpretation and is not rescue work for exposure/contrast mismatching. It also allows greater local contrast adjustment by dodging during the Gr.00 or Gr.5 exposures, as well as when burning.

‘I tried this project in lith, when I started printing after my first trip, and didn’t like it. I printed a lot of the pictures in lith and it just didn’t seem to suit it. I wanted it to have a consistency through the body of work and the temptation with lith was to tone all the icy ones and snow ones in gold so they were all a bit blue, and tone the other ones differently, but then it lost its identity a bit so I abandoned that.’

A more in-depth description of Tim’s printing process features in his book and, with some exceptions, the silver-gelatin prints from the book will be available as limited editions of 25. A deluxe edition of the book will also be available with three special limited-edition prints that will be in one size only and are unique to the book.

Exhibition and upcoming projects

An accompanying exhibition for Iceland: An Uneasy Calm is planned for The Lightbox gallery in Tim’s home town of Woking, Surrey, from April-June 2016. ‘I’m working on various other galleries to take it to,’ adds Tim. ‘I’d be very open to other interest if anyone would like to show it because I’d like to tour and may take it overseas if I can get support.’

Aside from the touring exhibition, Tim still has other photographic plans and projects for the future. ‘I want to go to Greenland and spend some time in a village there,’ he explains. ‘I don’t just want to cruise up and down the fjords – I’d like to spend some time on land.’

Tim adds: ‘I’ve got a lot of work on trees, which is mostly lith and toned, that I’ve been working on for some time and I want to produce a book on that. I’ve had a touring exhibition in Australia on trees and I’d like to produce a large-format book of this. I’ve got a lot of negatives that I’ve never printed and I’ve got a lot of old lithable papers stored away in freezers, so I’m looking forward to that.

‘I like to keep experimenting. I have a scientific background, so I’m quite used to the “lab work ethic” of changing one thing at a time, noting it and keeping records, and I think that’s really important when you’re learning. I’m super-critical: “That will do” doesn’t cut it. It won’t do – if it’s not right, do it again. When you make mistakes in the darkroom the most important thing is to figure out exactly what went wrong so that mistake becomes a learning step.’

Tim admits that he uses a small Panasonic Lumix model as a ‘snapshot’ camera, but says digital photography really doesn’t interest him much.

‘I’ve never yet made a digital print,’ he says. ‘I like making prints – it’s a manual thing. You start off with

a virgin piece of paper that you take out of a box, then you put light on it and you spread the light around with your hands, develop it and see it come up. You wait and then maybe you fix it and/or bleach it back and redevelop it in a different developer or tone it or do some local bleaching – whatever. Then you wash it and press it, and you end up with the same piece of paper with your artwork on it – the same piece you’ve handled all the way through. I like that, whereas seeing a virtual image on a screen and then pressing print just doesn’t have that manual craft bit that I like.’

Biography

Tim Rudman began his involvement with photography in the 1960s while studying medicine in London. He taught himself to print in the darkroom and, with his distinctive style of black & white printing, quickly gained some early recognition and publication. His work has been exhibited in over 50 countries, gaining many top international awards. Today he is respected internationally as a photographer, printer, author and authority on darkroom printing and toning techniques, particularly lith printing.

To see more of Tim Rudman’s work, visit www.timrudman.com. For more details about the exhibition, call 01483 737 800 or visit www.thelightbox.org.uk. Tim’s book Iceland: An Uneasy Calm (£55) is available from www.opasbooks.com.