With the arrival of spring and the start of more sunshine hours we can expect, in theory at least, to get back to our old friend the golden hour. It put in the occasional appearance over winter, but from now on there’s a better chance of being able to plan some good-weather shooting. The main beneficiary is, as usual, the landscape.

Landscape photography is a genre of photography that really does respond to planning, because while weather is the variable, potential viewpoints don’t change; they just need to be discovered and noted. Even in boring light, any time I spend checking out viewpoints and framings that will work in low sunlight is never wasted. I log them and wait for the right weather in which I think they’ll deliver.

The golden hour is in danger of becoming a cliché of landscape photography, which is a pity because it’s an exceptionally useful and attractive time for shooting. It’s not all about the warm glow by any means (I’ll come to that in a moment), but rather more to do with contrast and relief. Landscapes are large scale and, when taken wide, have fewer elements that stand tall than many people might think.

Most British landscapes tend to be rolling or level, rather than sheer, and so reveal little texture under overcast skies or a midday sun. Raking light, which is what you get when the light source is low, brings this out in the same way for small-scale surfaces such as brick and stone.

Moreover, you have a choice of different lighting effects that I call three-point lighting, because you have a potential full circle of lighting. Simply put, there is axial (sun behind the camera), side lighting from either left or right, and into the sun. Even if you start with just one of them, the others may also be available, depending on your location, so it’s worth looking around. All these factors coincide with the colour that gives the golden hour its name.

The colour comes from particles scattering in the atmosphere and bouncing the shorter blue wavelengths away. At the same time, the sun’s light has to travel through greater and denser atmosphere as it grazes the land.

Remember, too, that it’s not only the golden hour but also spring, and that engenders special seasonal qualities. Leaves are young and bright green, tending slightly towards yellowish. Above all, there’s the year’s first crop of flowers: look out for bluebells, daffodils, cherry blossom and so on.

Into the sun

High-contrast light will give you sharp and clear images, and means you can consider the inclusion of silhouettes

Shooting into the sun is one of the least predictable lighting situations because when the sun is low, the state of the atmosphere is the ruling factor. Sharp and clear, as in the image of the horse in the paddock, gives such high contrast that you might have to consider a silhouette.

When there’s a soft haze, the situation is very different, as in this example from China. Here, it’s the beginning of the day, facing into the late sunrise with a misty wash over the landscape. The all-important soft atmosphere does several things. First, it suffuses the scene in a golden glow, because we’re facing into it. Second, it gives a gentle version of the well-known ability of real fog to separate a scene into distinct planes. Third, and very valuable, the contrast is low enough to be able to hold landscape and sun in a single frame without clipping.

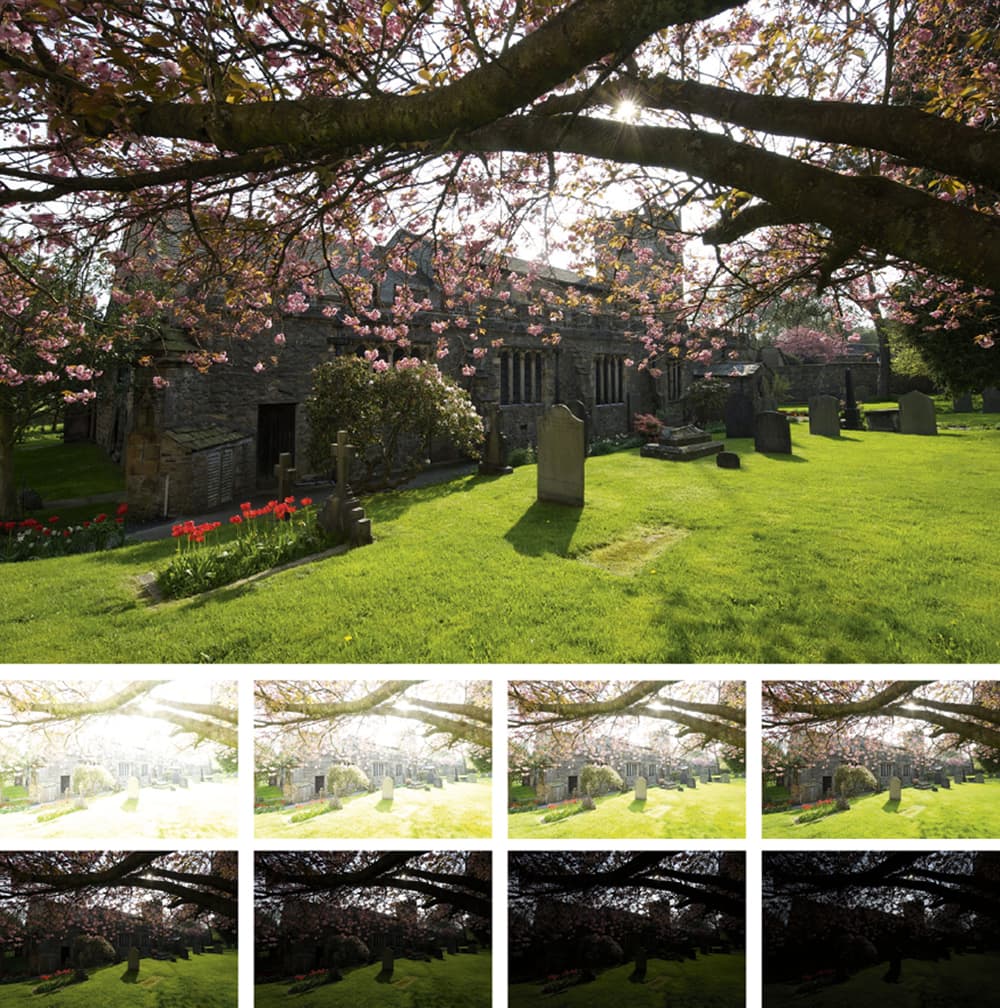

HDR on the fly

Here we see Michael’s example of how HDR can be used effectively

No, this isn’t about neurotic over-processing (just my opinion, obviously, but strongly held). HDR is a genuinely practical solution to shooting into the sun while retaining full, bright colours in what would otherwise be silhouettes. The cherry blossom in this Cumbrian churchyard were a classic spring scene, and a predictable problem for a shot in which I wanted to feature the sun shining through. The backlit blossom needed a very full exposure to record its colour, but the small- aperture sunstar needed several stops less if it were to keep its colour, too. That’s what HDR is for. Handheld? No problem. Just set the shutter to a fast burst (I used a Nikon D4) and a 9-stop range of bracketing. Image alignment and anti-ghosting in Photoshop’s Merge to HDR Pro worked seamlessly and fast. The file saved as a 32-bit floating point TIFF and opened in ACR, just like any raw file, with the difference being an exceptional dynamic range. Using the normal ACR sliders, and avoiding Clarity like the plague, with some local radial filters, the result keeps all the normal photographic qualities.

Your choice of colour temperature

The golden hour used to mean what it said – images suffused in a golden hue that’s conventionally likeable. But all the time? Frankly, like any good thing, it can become a little tedious. Nor is it necessary. Let me argue the case for a cleaner, more neutral colour temperature.

Our vision adapts to colour casts and we ‘see’ landscapes that are lit by a low sun as more normal (for which read neutral) than colour film or a digital daylight setting. When shooting raw, the colour-balance settings are kept separate from the image file, so you can choose whatever you like when you process. I like to have such a choice. I shoot auto white balance simply because you have to choose something, and increasingly these days I leave it at that, or tweak towards warmth. There’s no universal correct white balance; just what looks right to you.

Crosslighting

Maximum landscape texture comes from some form of side lighting. it gives the highest visible contrast between lit areas and long shadows. as a rule of thumb, a sun elevation of between 10° and 20° delivers this well, so long as the air is clear. Look for this at the tail end of one of those cold showery fronts that pass through in the spring. Even so, don’t rely on crisp light to last for a moment longer than you can see it, because when it goes, or a cloud moves in front, it disappears quickly. This shot is from spring in the high savannah surrounding Bogotá, Colombia, where the air is clearer because of the altitude of 2,600m.

Michael Freeman is a British author, photographer and journalist. He has written more than 40 books on photography, focusing mainly on technique and practice. To learn more, visit www.michaelfreemanphoto.com