Kevin Cummins

Kevin Cummins was born in Manchester in 1953. He spent ten years as the chief photographer for NME, he has contributed to publications wordwide and he remains one of the UK’s foremost music and portrait photographers. See his website for more

It’s little surprise that Kevin Cummins ended up as a photographer as he received a camera for his fifth birthday present and both his father and maternal grandfather had home darkrooms. After developing his own darkroom skills at a young age he studied graphic design and photography in Salford, ‘much to my parents’ annoyance… they never thought it was a real job’.

He regularly viewed the reportage photography in the Sunday supplements but admits, ‘I was more interested in portraiture. The three photographers whose work I really liked were August Sander, Bill Brandt and Diane Arbus. That taught me a lot about connecting with people, how to photograph them. Arbus had only just killed herself when I started my first year [at college], but that idea that you didn’t just turn up and take a picture, you could spend days with somebody to craft a picture, stayed with me.’

Cummins graduated when the punk rock era was exploding. ‘I started shooting that because, obviously, you don’t walk out straight into a job. I went back [to college] for a year teaching and I also did two days a week printing in a darkroom for some industrial photographers, so I had access to darkroom and camera equipment. I was able to get out and shoot bands and I quickly got a piece published in the NME, about Manchester music, in July 1977.’

The hard yards

The life of a rock and roll photographer may appear to be glamorous but it is anything but. Cummins explains, ‘When I did a live show for the NME you’d go to the gig and stay sober because the darkroom was about ten miles outside Manchester. I’d drive there after the gig, process it, print it, contact sheet it, pick the best four shots and wait for those to dry. I’d get back into Manchester about six in the morning and put it on Red Star Parcels, the only way of getting pictures down to London at the time.

Then, if the NME remembered I’d shot it, they’d go and pick it up… you might get one picture in the following week’s paper and you’d get £6.50 for it for 14 hours of work.’ The Manchester music scene of the late 1970s was vibrant with bands like the Buzzcocks, The Fall and Joy Division building up followings.

Cummins reveals, ‘I’d do regular work for the NME, plus I could do stuff for the other music papers. I lived in Manchester and I just shot everybody. [Journalist] Paul Morley and I were commissioned to do a piece about Manchester music, so we did three or four bands. There was a band called Spherical Objects and the singer was Steve Solamar, who was an interesting bloke. He was the fulcrum of the piece until we sat down with Joy Division, talked to them properly and realised they had a better plan and were hungry.’

Joy Division, Epping Walk Bridge, Hulme, Manchester, 1979

He shot his iconic picture of Joy Division on the Epping Walk Bridge in Hulme, Manchester, in 1979, the year before the band’s lead singer Ian Curtis took his life. He adds, ‘Now there’s this huge mystique around Joy Division and they’re bigger than they’ve ever been, but at the time they were a peripheral band. They were the kind of band the music press gets excited about because they did a great first album. They were exciting but, at the time, the Buzzcocks and The Fall were probably bigger than them.’

The Smiths, Manchester

Moving to London

In 1987 Cummins moved to London as he felt he’d done all he could in Manchester, though he made sure he had work lined up when he made the move. He laughs, ‘I threw my lot in with NME and didn’t do anything for other music papers. Pretty much just as I moved down all the stuff in Manchester with Acid House, The Stone Roses and Happy Mondays exploded, so I was spending about three days a week coming back to Manchester having moved down to London… great timing!’

Despite having now lived in London for over 30 years he often goes back to Manchester, especially to watch his beloved Manchester City playing football. He admits, ‘I’ve pretty much painted myself into a corner by concentrating on Manchester stuff which, in a way, is why the Britpop book is quite nice, even though there’s Oasis running through it. It just shows I’m allowed to leave the city occasionally!’

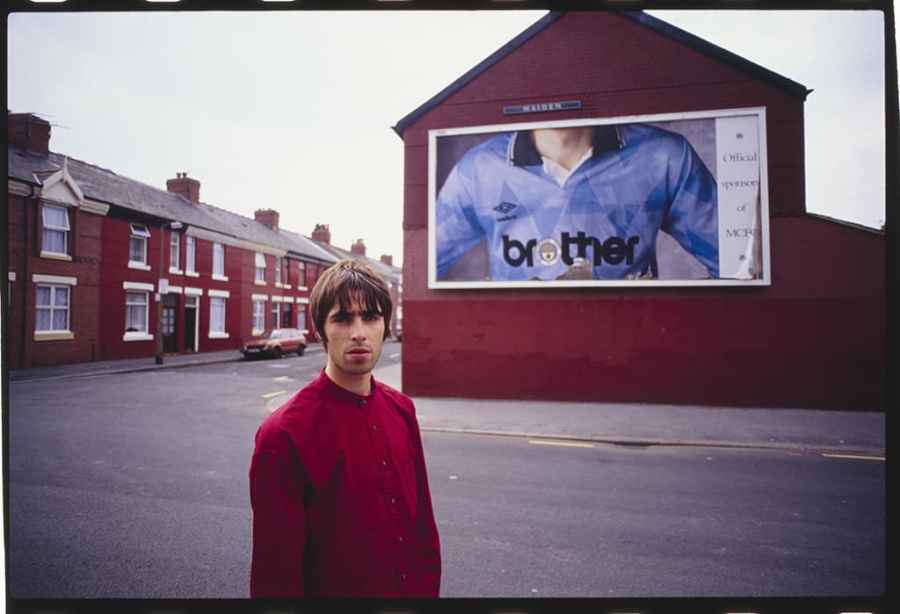

Liam Gallagher, Oasis, NME feature, outside Manchester City’s old ground, Maine Road, July 1994

Britpop brought to book

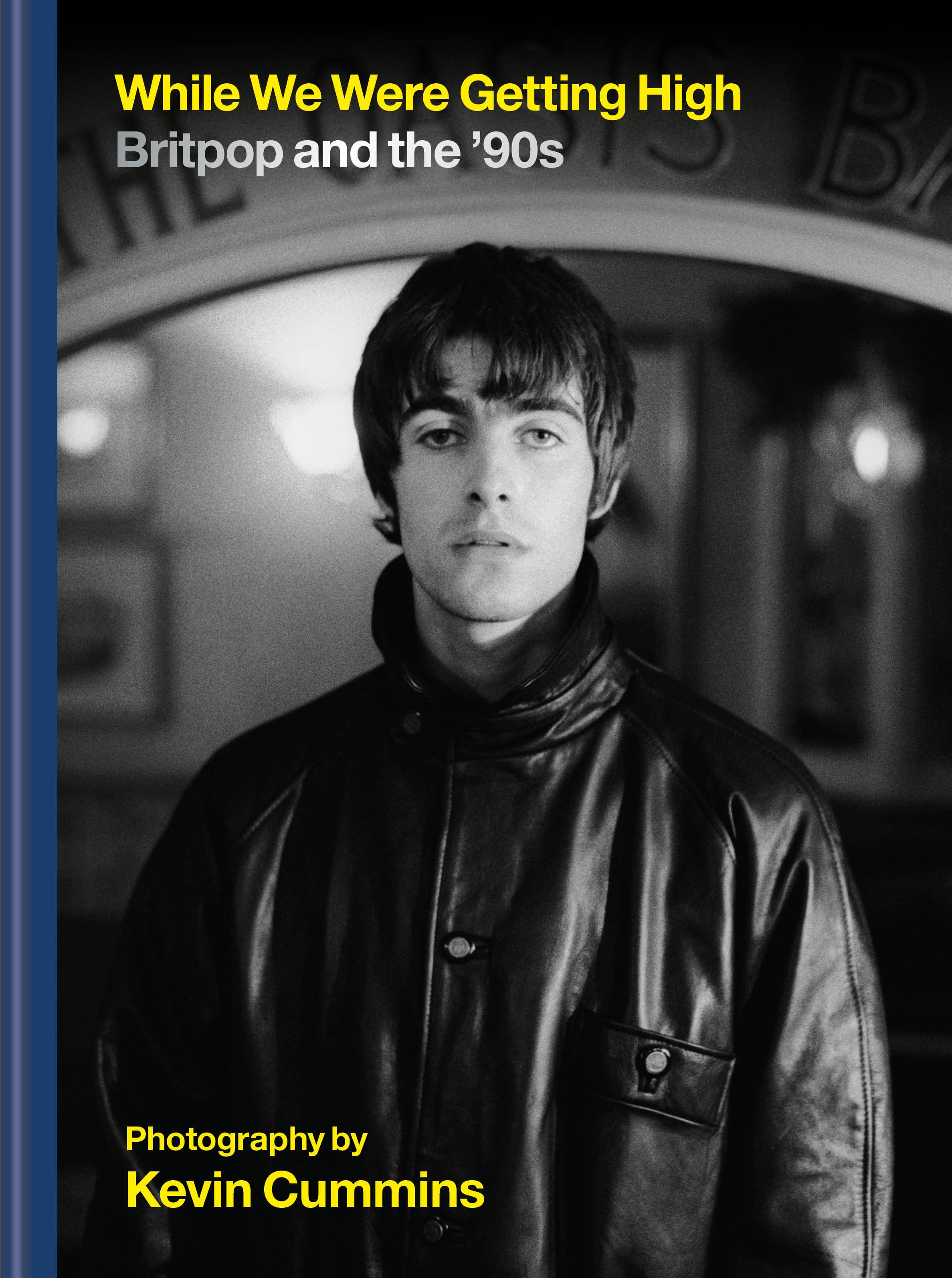

His new book, While We Were Getting High: Britpop and the ’90s, features over 200 images shot throughout the 1990s when British bands like Oasis, Blur, Pulp and Suede were dominating the charts and the tabloid headlines. Despite the vibrancy of the imagery in it Cummins wasn’t 100% sold on the idea: ‘I wasn’t completely convinced by it because I think it’s quite hard to sell a book on a genre of music. Generally, with music books, it’s much easier if you stick to a single band.’

The Charlatans, Brighton, January 1994

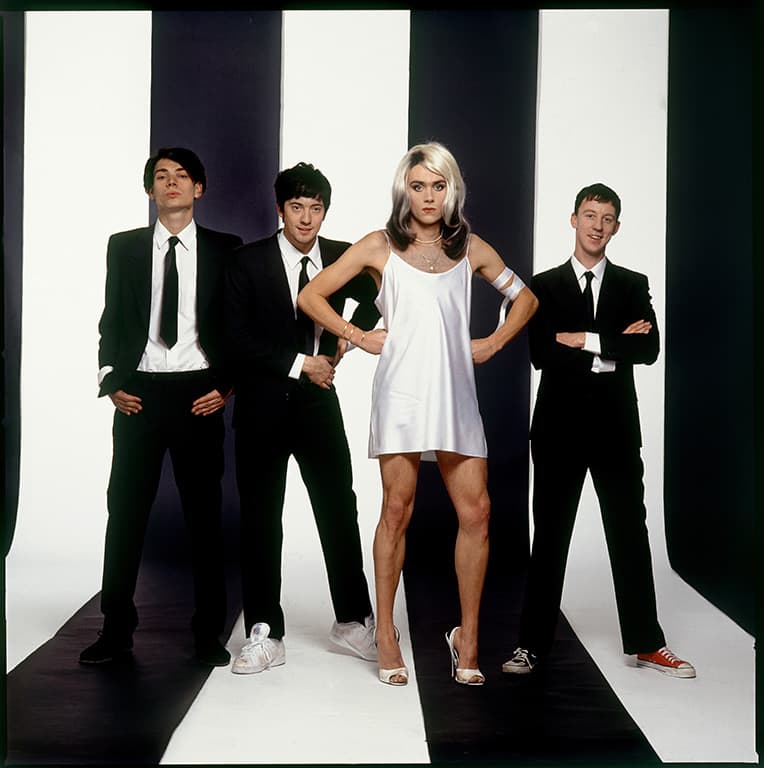

He sourced his archives from Getty and ended up looking through over 50,000 photographs for the book. He explains, ‘When you do a shoot for a music paper it’s quick. You’d have to choose the best half dozen pictures, print those, put them in the file, they’d be used the following week and then everything just gets filed. I managed to get quite a lot of stuff that hadn’t been published before in [the book] but there’s no point in putting 300 pictures nobody has ever seen because they want the picture of Noel and Liam in [Manchester] City shirts and they want the picture of Blur dressed as Blondie, so you’ve got to do that.’

Blur as Blondie, NME shoot, studio, December 1991

Although he is happy with how the Britpop book has turned out – it also includes interviews with musicians Martin Rossiter (Gene), Noel Gallagher (Oasis) and Sonya Aurora Madan (Echobelly) – Cummins was careful with its contents. ‘It’s quite a difficult thing putting a book out celebrating Britishness in this fairly toxic period we’re living through, which is why I was careful not to overdo the Cool Britannia thing. I didn’t want flag waving all over the book. There’s only one flag in the book and that’s a black and white of [Blur’s] Damon [Albarn] in Tokyo.’

Radiohead, Gloucester, August 1994

Changing times

Cummins has spanned the analogue to digital eras but he retains some of his basic principles. ‘I try to shoot digitally like I’d shoot with film. I think every 36 frames is costing me 20 quid. What has changed enormously from analogue to digital is the sense of camaraderie with other photographers. After a session we were all used to going to Joe’s Basement, or one of the other labs in Soho, and going to the pub next door while your film was being clip tested… moaning about your editor or something. Now we do a shoot and go home… it’s become a very isolated profession in a way. You meet the person you’re photographing – that’s it, end of story. Then you go home and then you do all the work, rather than the lab, and you get paid less for it.’

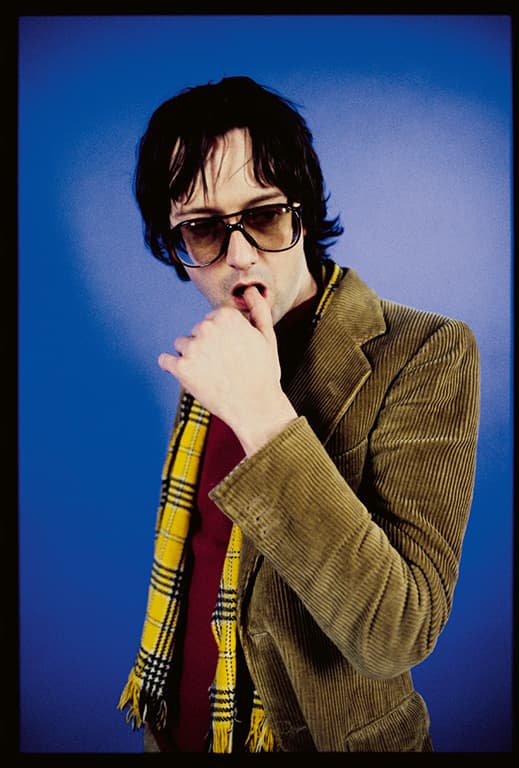

arvis Cocker, north London, December 1998

Cummins had always shot with Nikon film cameras but with digital he changed brands. ‘Canon was much further ahead than Nikon at the time. All of a sudden I had to learn to use a different camera and, just like when you use a new batch of film, you’re likely to make the odd mistake. I think you learn by those mistakes. A couple of friends had used Photoshop and they showed me the basics of how to use it, so that’s what I did and that’s all I do. I’ve got a Canon scanner, Canon cameras and lenses and whatever Photoshop is called these days.’

He continues, ‘The camera body doesn’t necessarily matter to me, just that it’s not going to fall apart, but I will always buy the best possible lens. I’ve got a Canon 16-35mm, a Canon 85mm f/1.2, which is a really lovely lens, an 85-200mm and, obviously, a 50mm. My 50mm is a close-up lens as well so you can take a picture of someone’s knuckle or a ring on their finger. So that’s all I need. I’ve got a 1.5x converter that I sometimes stick on the 200mm.’

Cummins does prefer to have a viewfinder through which he can view 100% of what he’s taking. ‘If I had a Nikon FM, say, I was getting 95% of what I was seeing in the viewfinder so when I’d process it I’ve got more on the film than I wanted which was really irritating. As soon as I could afford it, I bought Nikon F3s, which were as close as you could get to that edge-to-edge experience.’

Portrait influences

For someone who has spent over 40 years photographing musicians Cummins has a surprising confession. ‘I never liked music photography much. Obviously I’m interested in it because that’s the genre I’ve worked in but I find a lot of it too confrontational. When you look at a couple of my pictures of Liam Gallagher they’re quite sensitive, but people don’t want sensitive portraits of Liam – they want him spraying beer into your camera lens and I’ve never been the sort to do that kind of thing.’

He adds, ‘I’m much more interested in getting a soulful portrait of somebody. That’s why I’m more interested in portrait photographers and what they can offer – massively undervalued people like Jane Bown. Jane’s pictures were an enormous influence on me and even [Lord] Snowdon was. Snowdon was a massively underrated photographer and I learnt quite a bit from reading about him and looking at the way he worked.’

Cummins regularly shoots commercial work for an Adidas capsule leisurewear brand and admits he is ‘lucky’ that at this stage in his career he can pick what he works on. During 2021 he is planning a new take on his Joy Division book Juvenes. ‘It’s an extended version of a limited edition I published about 14 years ago. There were only 226 copies… half the people who bought it didn’t even unwrap it, so now I’m giving them the opportunity to see what’s in it. I keep saying to people who’ve got Juvenes and still haven’t opened it, “I might as well just put a blank book in there.” People would never know and by the time you did know it’d be too late, I’d be somewhere else!’

Kevin Cummins’s top tips

- People ask, “Will you look at my portfolio?” If someone has just done a gig and has put it on Facebook occasionally I’ll have a look… and they’ve posted 800 photographs taken at a gig. My advice is to put five on there… less is more. Instead of shooting 800, look through your camera and wait for the magic moment. Don’t just assume it’s going to be there because you’ve shot a frame every second of the gig.’

- Plan ahead. If I was doing a complicated lighting set-up in the studio – for instance, the New Order shots where there’s three silhouettes in the background and one spot lit in the foreground. We spent eight hours the day before with my assistant and a couple of friends trying that shot out in different ways, taking it to the lab, getting it processed and looking at how it was working best. When New Order turned up they got in position and it took 15 minutes. They don’t need to know I spent a whole day working that shot out.

- ‘You’re not the most important person in the room – your subject is – and so you’ve got to get them into a position where they’re relaxed with you and also where they’re not just looking at the front element of the lens. They have to look at you, that’s where the film plane is and then it works. If they’re just staring at the front element it doesn’t work and it’s not a good portrait.’

- ‘I worked for the NME for 20-odd years and very rarely would anyone say, “This is great. I love this cover.” The only time you ever get any feedback is if someone doesn’t like something. You have to have very thick skin and you’ve got to assume that people like your work, because they won’t commission you if they don’t.’

While We Were Getting High: Britpop and the ’90s, by Kevin Cummins, is published by Octopus Books, ISBN: 978-1- 78840-220-0, with an RRP of £30. To find out more go to the publisher’s site

Further reading

How to photograph live music

Portrait photography tips