Earlier this year, I was invited to act on the judging panel of the Shipwrecked Mariners’ Society’s annual photography competition. I, along with a host of others, stepped on board HQS Wellington moored on the River Thames in London and prepared for the daunting task of poring over a mountain of images to whittle them down to what we thought were the best in each category. As can often be the case with competitions, rarely did we all agree on image choice – apart from a few exceptions. Quite incredibly, those exceptions all seemed to be by the same photographer – a Reverend Dr Richard Hainsworth.

One of those images went on to be awarded first prize in the People and the Sea category. Called ‘Solace’, it is a haunting image that lives up to its name. It shows one of Antony Gormley’s lone figures, silhouetted against a gorgeous blue twilight, stands with his feet immersed in the glassy ocean, and gazes out into the impossible distance of the horizon. Before him, the sky seems to hint at the shy beginnings of an ethereal white light as if Heaven itself is about to open its gates and welcome our solitary subject into the fold.

‘I was very pleased that you and the other judges liked this image,’ says Richard from his home in the village of Northop in Flintshire,where he is currently serving as the vicar at Northop Hall. ‘It’s one of my favourites. That shot was taken just after Christmas last year. This is a time when vicars are not really at their best and need some R&R, especially if they also have a toddler at home [Richard and his wife Laura are the proud parents of a two-year-old boy called Jacob]. Honestly, I was feeling quite burnt out at that point.’

Describing himself as ‘an introvert’, he enjoys taking a few hours to himself and often uses such opportunities to go to the coast. ‘I loved visiting Antony Gormley’s “Another Place” exhibit on Crosby Beach, near Liverpool,’ he says. ‘There are 100 life-size statues of the artist, spread across a couple of miles of beach. Many of them disappear in the water at high tide. I spent a happy few hours slowly recharging and exploring different compositions, but mostly using the same theme. I wanted to express the feeling of being alone, but not lonely, which is why I called my image “Solace”. Time and tide have added to this particular figure in a way that makes him look like he’s wearing rather scruffy, but comfortable, clothes. I saw him as being comfortable in his environment, looking at a great expanse of not very much, but being content, even if the water was about to come up to his neck. To him the sea is peaceful, rather than chaotic.’

‘Solace’. This image caught the attention of the judges in the 2016 Shipwrecked Mariners’ Society Photographic Competition

Across borders

It seems odd to get hung up on the fact that Richard is a reverend, but there is something unusual about it, especially considering the strength of his images. It’s difficult not to ask if his calling as a man of the church interplays with his passion for photography but, as he says, it’s not necessarily a strange thing to suggest.

‘I originally studied maths and physics at university before training to be a vicar,’ Richard explains. ‘I think what this background, my theology and my photography have in common is the desire to explore and reveal the structure and order that’s underneath the seemingly random confusion of life. I really enjoy the moment when a scene or event crystallises into a composition that has balance and harmony and feels “right”. For me, there is a spirituality to this, which I don’t think you have to be explicitly a member of a particular religion to experience.

He also enjoys constructing composite images, describing some of his photography as ‘trying to uncover an order in the outer world’. He continues: ‘Some of it is about creating visual stories and trying to give expression to how I might be feeling inside or what I might be imagining. If things really work out, maybe it is possible to do both at the same time.’

What’s especially pleasing about Richard’s work is that it spans genres. His website is awash with the evidence of a man unafraid to try his hand at anything. Richard identifies this as a result of his labelling of himself as an ‘amateur’ – a label that gives him the freedom to choose if he wants to be a specialist or to embrace the freedom of traversing the boundaries of genre.

By his own admission, Richard is a man who gets bored easily and desires new challenges. Currently, you’ll find him stalking across the beach with his camera in hand. This is largely down to the fact that just a year ago he found himself hesitant to produce coastal landscapes and use wideangle lenses. It’s all about proving himself wrong. That’s why his output is so vast. In the past few months, he’s learned to enjoy macro, nature, sports, events and street photography (he talks about one of his stunning street shots shortly).

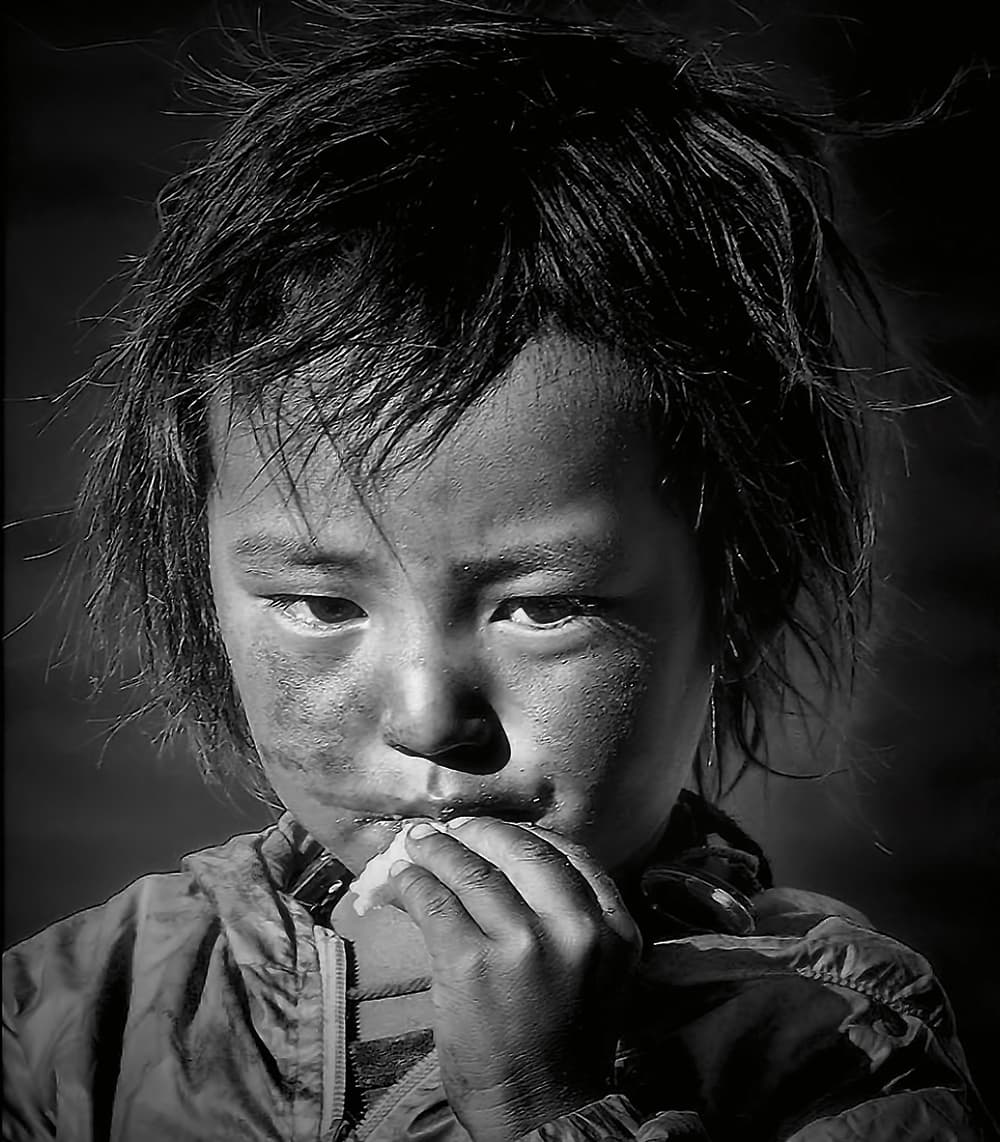

‘Tibetan Boy’. One of the many images Richard took for the National and International Salons of Photography in 2014 and 2015

Richard says there are potential new images everywhere, and it’s a fine lesson to take on board. Add to that the fact that photography is an excuse to visit new places and play with a range of new photographic toys, and it’s an attitude that can’t fail.

Talking of lessons, Richard looks back at the earliest days of his hobby and can’t help but identify one major step he’s taken in terms of how he shoots.

‘For a time, back in the late 1990s when I was first into photography, I shot for a few months with only an all-manual eastern European camera and slide film,’ he says. ‘And when I say all manual, I mean no lightmeter, set the aperture with a lever (and the viewfinder goes dark) and focus by hand. I took a lot of horrible frames with this, but it did cure me of snapping away furiously and helped me discover photography as something often more meditative. Now, with a 6fps or 8fps digital camera in hand, it is easy to relapse when I get carried away, but I still try to really see a scene without the camera to begin with, and visualise what I want the image to look like, before looking through the viewfinder. On the other hand, returning to photography via a digital route has encouraged me to take more risks and explore beyond the image I first thought of, to see what else might be there.’

Scene seen

When I ask what it is he especially looks for in a scene, Richard adds: ‘I tend to like my images to be very simple, with a few elements clearly related to each other. I tend to construct them from front to back, working out what I like in the foreground, then the middle, then the background. When I turn up at a location or event, I’ve usually already tried to research and imagine the sort of images I want, which helps me focus and get started. But then, if I can get the imagined shot quickly, I like to simply spend time with a location and see what appeals. It will tend to be something quirky happening, or a simple geometric pattern, or again a particularly simple composition that I feel captures the essence without distractions.

‘Recently, I have kept going out looking for the standard vivid sunset and golden-hour light, and then finding that I actually prefer the incoming storm clouds or the blue light just after the sun has set. But again, it is mostly about keeping things fresh and enjoying adapting to various light and weather rather than always seeking out the same conditions.’

When pressed to identify his favourite image, Richard struggles, as most of us do, to pick just one.

‘Can I have three or four?’ he says. ‘The first is called “Thou Shalt Have a Fishie”. It’s my favourite photo of my little boy, Jacob. I like to think it captures something of the wonder and imagination in small children. And I think Jacob, who was 18 months at the time, looks very handsome! The fish is an aquarium shot. Jacob was shot in my home studio using two softboxes and a Speedlite, and the bubble is part photo, part digital drawing.

‘Thou Shalt Have a Fishie’ holds a special place in Richard’s portfolio. The shot of his son Jacob is merged with an aquarium image of a fish

The second of Richard’s favourite images is another composite called ‘Carry Me Over’. ‘This is the first time I had a composite image that I felt really worked,’ he says. ‘The background was an early attempt at landscape photography in Skye, which I felt had something missing. The figure is a re-enactor, whose dog got onto the frame and had to be carried off. For me, it is a story of care and concern in a wild world.’

‘Carry Me Over’, a shot that Richard identifies as one of his favourite images and the first time he felt his attempts at composite images worked

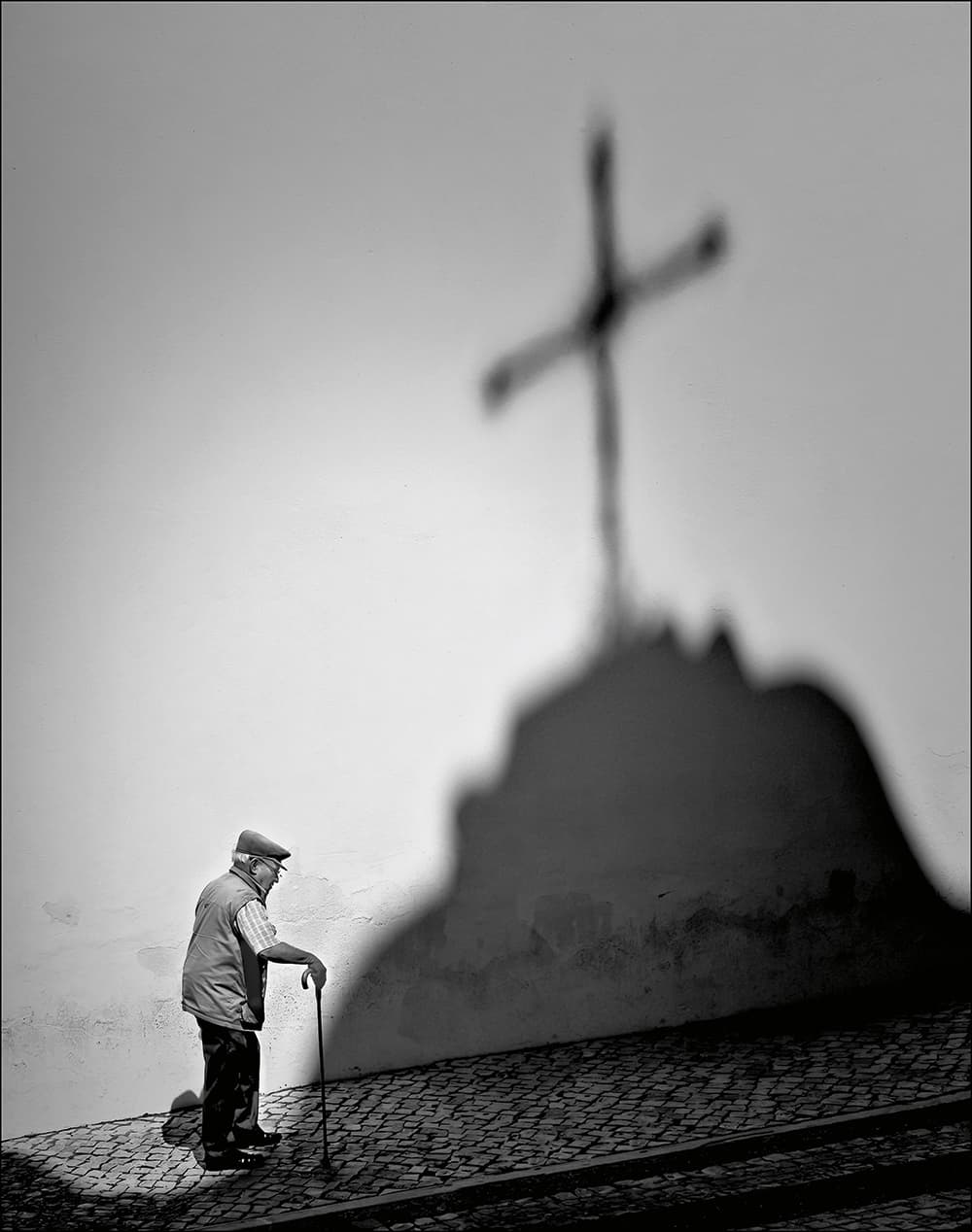

The third choice is one of Richard’s street images and is, in my opinion, quite possibly the best of all his photographs. He says: ‘This is called “Ascent” – not a composite this time, but a street shot from Silves, Portugal, in 2015. I saw the shadow and the older man approaching when I was at the far end of the street. Immediately, I could see the image I wanted and the story it would tell or questions it might ask. Is the shadow a dark omen? Or a comfort on the journey? I ran all the way up the hill and just managed to get onto the church steps to take this shot before he reached the shadow. Apart from the black & white conversion, there is little post-processing here. This is probably my favourite. It’s certainly the most “vicarly”!’

‘Ascent’, Richard’s favourite shot. He found this shadow on the streets of Silves in Portugal in 2015 and saw it as an opportunity too good to resist

Richard’s kit

- Canon EOS 5D Mark III.

- Canon EOS 7D as a back-up.

- EF 17-40mm f/4L lens for landscapes.

- Tamron 24-70mm f/2.8 VC lens as a walk-around lens.

- EF 50mm f/1.8 and EF 85mm f/1.8 for portraits, particularly of his little boy.

- Tamron 90mm macro lens.

- EF 70-200mm f/2.8, because it makes beautiful images at medium range.

- Sigma 150-600mm S for reach.

- Manfrotto carbon-fibre tripod with three-way head.

Richard processes all raw files in DxO Optics Pro 11 and edits individual images with Serif PhotoPlus X8 and Topaz Adjust, B&W Effects and Clarity.

About Richard Hainsworth

Richard became vicar of Northop, Northop Hall and Sychdyn in the diocese of St Asaph in 2014. He is also a photographer who has won various photography medals and competitions. In 2015, he was awarded his LRPS. He received his second GPU Crown in December 2015, his CPAGB in April 2016 and AFIAP in June 2016. His images have appeared in the press, in material for The Church in Wales and in advertising literature, and he has shot weddings of family and friends, and voluntary/community projects. www.andtherewaslight.co.uk.