Black and white film still has the ability to inspire passion and creativity in its users, even in this digital age. We talk to three photographers who continue to embrace the medium in very different ways, and still shoot black and white film.

Esther May Campbell

Film photography has been in Esther May Campbell’s blood since childhood. She was given a Polaroid camera when she was eight years old, but it was the Olympus OM1 she received in her early teens that really changed things.

‘My teens were quite tricky times,’ she explains. ‘I was at a fairly dishevelled all-girls state school, and there was a certain amount of bullying. Taking pictures helped me navigate some of those relationships, and being in the darkroom meant I could escape and process the pictures of the world around me. It was bliss.’

Despite relishing the escapism photography offered, Esther had no intention of following it as a career. However, having worked her way up the ladder in television production, she discovered it was an industry that didn’t marry particularly well with the commitments of bringing up a daughter.

Pete’s Hands, taken on an OM1 at Elm Tree Farm, which is staffed by adults with learning disabilities

‘I came home to pick up a camera again and photograph what was immediately around me,’ she says. What to shoot was never in question – it was always going to be black & white, as this best expressed her interpretation of her environment. ‘I see light better than I see colour,’ she reveals.

‘I can look at something and abstract something from it because of the way the light is falling. I used to draw a lot with different granite pencils, but I’ve never painted. I do sometimes put a colour film in the camera, because there might be less going on in a scene and it’s soft, but I don’t see what to do with colour – it’s as if I’m missing something.’

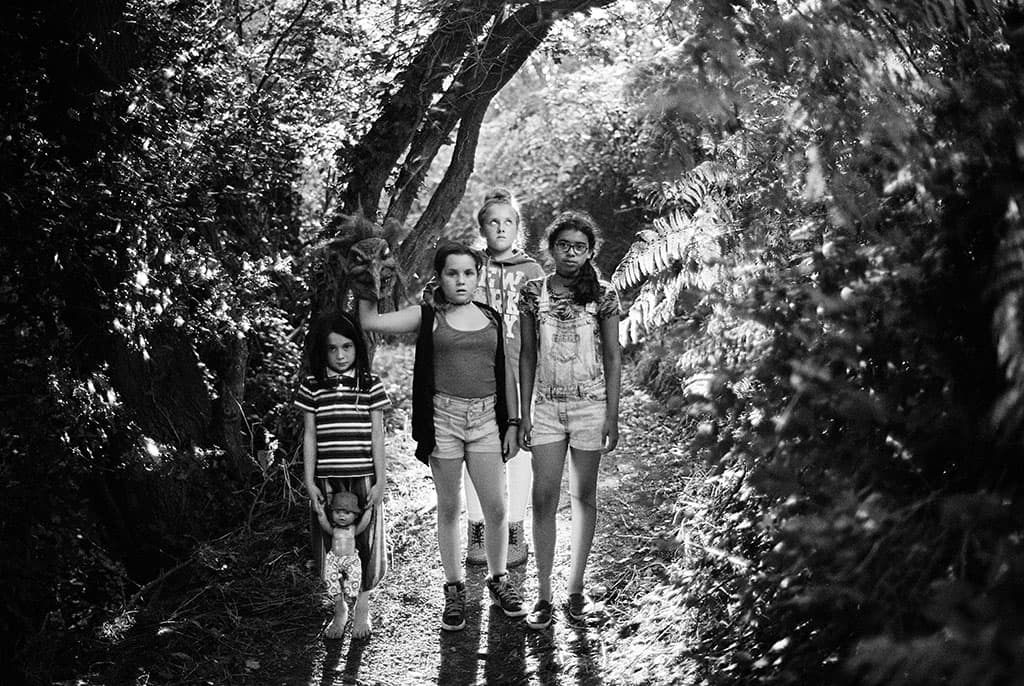

Girls and Witch Head, taken on an old Kotak Retina IIIc, on the edge of an allotment. From Out of Darkness

Film flaws

Esther talks a lot about rhythm. When she recalls processing film in the darkroom as a teenager, she speaks of ‘working to the rhythm of film and chemicals and their needs.’ Then, for example, in the case of documenting a farm staffed by adults who have learning disabilities, she explains, ‘The more I went, the more I came to understand the rhythm of the place.’

This almost unconscious search for rhythm underscores the energy behind her work, and the use of black & white film only emphasises it further. ‘I like the unpredictability of film,’ she says. ‘There’s an element of magic in the unknown. I like the glitches you get when something doesn’t work, such as the film being scratched or light bleeding into the lens, and what it does to the image.’

It will come as no surprise to learn that Esther is not precious about her cameras. She rotates between an Olympus OM1, a Kodak Retina IIIc, a 5x4in Graflex and a Rolleiflex her grandfather gave her when she was 18. ‘They’re all old and pretty ramshackle,’ she says. ‘I’ve fallen in a river with the 5×4 and it survived.’ A

s for film choice, she uses whatever she can get her hands on, and sends it off to be developed, often two or three months later. This waiting game is part of the process. ‘There might be some jewels in there and I won’t know,’ she says. ‘It’s like a goody bag.’

When she does finally see the results, it’s via a scanner rather than an enlarger. ‘I moan about the scanning, but quite a bit of editorial happens in the process. It allows me to realise which images I’m not going to keep, and which ones I might spend a bit of time on. The scanning becomes a chance to get to know the material.’ Some photographers nowadays feel restricted by the film process, but for Esther, that restriction is all part of the creative fulfilment.

‘As Orson Welles said, “The enemy of art is the absence of limitations”,’ she concludes. We could all learn something from that approach.

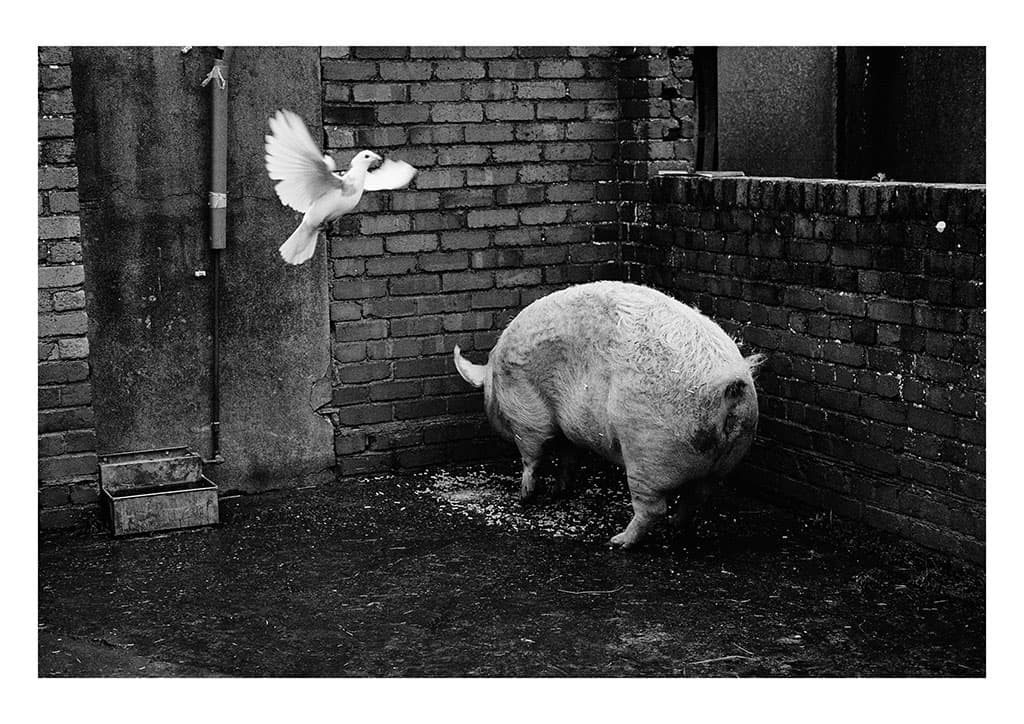

Pig and Dove, taken on an Olympus OM1 at Elm Tree Farm. Spending a year there, Esther became attuned to the patterns of the place

Esther’s top tips

1) If you haven’t shot black & white film before, get hold of some b&w photo books and spend some time with them. Pick an image you like, then work out why you like it. It might be something about expression, or light, or the amount of black, white or mid tone in the image. Eventually, you’ll see how it affects your own work.

2) Choose your photographic tools and use them to go deep rather than wide. Because you can do everything with digital, with film you have to learn discernment, and what you’re not going to do.

3) Don’t process your film straight away. Over Christmas, I had some films processed from the summer, and it was wonderful to see them for the first time.

Bristol-based Esther began as a runner for TV and film production companies, eventually directing episodes of Doctors, Hollyoaks and Skins. She continued with her personal photography alongside. During lockdown, she has been sending out ‘photography care packages’ to local children, who use the camera she supplies, before sending back the film for processing. See her website.

Robert Canis

Robert’s name will be familiar to many AP readers. His creative colour nature photography has graced the pages of photography magazines for many years. However, when lockdown hit in March 2020, he decided to purchase a Hasselblad. Since then, he hasn’t touched a digital camera and, as he puts it, ‘I haven’t missed it one bit!’

As a keen advocate of photographic projects, Robert wanted to spend time documenting the North Kent Marshes, where he lives. The marshes stretch from Dartford in the west to Whitstable in the east, and are recognised as an important natural wetland. ‘They are fringed by industry,’ Robert explains, ‘with rotting barges and power stations, and black & white seemed the natural medium to portray them. I had tried to photograph them using digital, but I didn’t get the right feel, and the aesthetic of black & white film is completely different.’

Originally, he set out to use a 35mm SLR, but found it ‘a bit too easy’. Never one to shirk a challenge, he decided to try the Hasselblad. ‘It doesn’t have a meter or batteries, and with only 12 exposures, each frame costs money, so you have to think before you take the picture.’

Building a system

Along with his Hasselblad 500CM, which dates from the 1980s, Robert’s system includes 50mm, 120mm and 250mm lenses (equivalent to 28mm, 75mm and 135mm in full frame), as well as film backs. And it wasn’t long before he replaced the waist-level finder with a prism finder.

‘If it rains or snows, or you’re shooting in mist,’ he explains, ‘condensation forms on the waist-level finder’s focusing screen. But the prism finder is brilliant, because it enables me to see the whole frame so clearly.’

When it came to film choice, Robert plumped for Ilford FP4 and HP5. The latter in particular he describes as ‘very forgiving, and with a lovely grain structure that can be pushed to ISO 3200 if needs be. In addition, it’s substantially cheaper than Kodak film.’

It was also important to him that he could see the grain in his photographs, which meant Agfa Rodinal was the ideal choice of developer. ‘It’s incredibly economical, and gives a really nice, pronounced grain,’ he says. Processing his film was trial and error at first, with mistakes manifesting themselves in the form of bromide drag (uneven density across the negative).

Industry at night on the banks of the Swale, Kent

He realised quickly this was a result of his agitation technique, and that Rodinal required a much softer, more rolling action. Once that was nailed, he hasn’t looked back. Covid restrictions mean it isn’t currently possible for Robert to use his local community darkroom to make prints, so in the meantime he has come to an unusual solution in the form of scanning.

‘I would have loved to have splashed out on a Nikon Coolscan 9000, but at £3,000, it was beyond my reach!’ he laughs. ‘I went on to various forums and also watched YouTube videos, and the overriding feeling was that if it was set up correctly, a digital camera could produce extremely good results.’

As such, he uses his 45MP Nikon D850 with a 105mm macro lens to photograph his negatives, and this gives him a file big enough to produce a 34in-square print.

‘Holding the negatives flat was the biggest challenge, until I came across the Essential Film Holder (www.clifforth.co.uk),’ he says. ‘You place the holder on a light source such as a light pad, position the squared tripod-mounted camera above it, then feed the film through, and away you go!’

Once he has his scanned raw file, he imports it into Lightroom, converts the negative image to a positive using Tone Curves, then tweaks it using the Gradual and Radial filters, and the Blacks and Whites sliders until he achieves a tonally balanced image.

Robert’s top tips

1) When you shoot black & white, it doesn’t matter how dramatic the sunrise or sunset is – it isn’t going to work. Look instead for texture and mood.

2) Use a lightmeter. I have an extremely accurate old Soligor spotmeter that takes a one-degree reading. It allows me to meter according to the Zone System and process accordingly.

3) Don’t bracket. That suggests you don’t know what you’re doing. Look at the scene and expose for it accordingly.

4) Be consistent, both in your shooting and your developing. I record everything – where I took the reading, how I adjusted it, the developer I used and the frequency of the agitation – in a notebook. And on top of every neg sheet I’ve noted the film, its rating, the developer, temperature and agitation. Note-taking is a must if you want to get consistency.

Robert is known primarily as a nature photographer, and his interest in wildlife began even before his interest in photography. When he was about 11 years old, his mother put a camera in his hand, and from that moment he only wanted to be a wildlife photographer. Having worked as an assistant and a printer, he decided to go freelance in his early 20s, and has never looked back. While many of his personal projects are undertaken close to home, he also leads workshops in places such as Poland, Finland, Norway and the Czech Republic. See his website.

Francesco Neri

Some years ago, Francesco Neri read a quote by a writer, which said, ‘Without writing, I’m just stuck with life.’ It resonated with the photographer, who feels similarly. ‘Without photography, I’m just stuck with life,’ he says, laughing.

‘Photography for me is not about an aesthetic – it’s about getting to know more about my own environment and the world itself.’ Francesco does this by means of a Deardorff 10x8in large-format camera, with 305mm G-Claron and 210mm Symmar-S lenses, which he uses to make portrait images that follow a similar ethic to the likes of August Sander, Nicholas Nixon and Judith Joy Ross – all photographers that he admires.

‘At the beginning, I wanted to fit in with the tradition of landscape photography,’ he explains, ‘because in Italy we didn’t have a tradition of portraiture, but I struggled.’

He started to take portraits of friends and their families, and suddenly found something of himself in the images he was making. Living in the region of Emilia-Romagna, he is surrounded by farming land and agriculture, so it seems only natural that he gravitated towards photographing the farmers who work there.

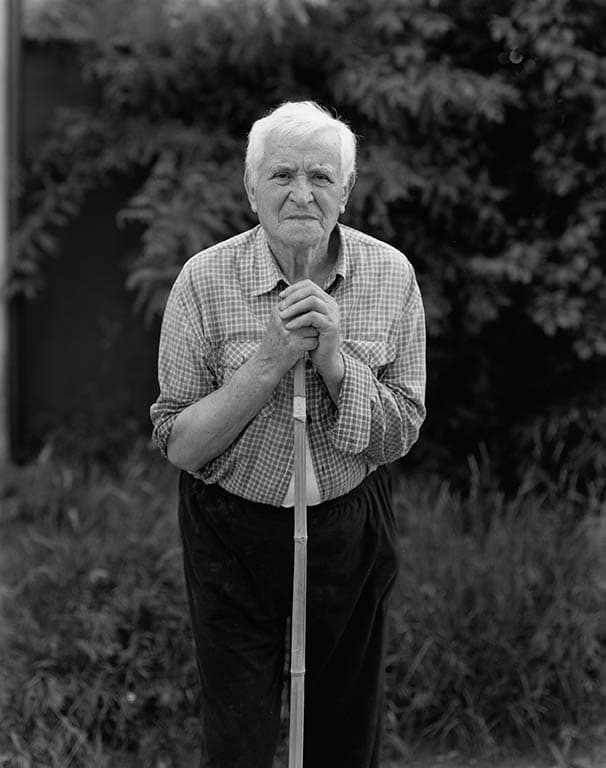

Solarolo, 2018. ‘With 8×10 you can control every inch of the picture,’ he says

‘I’m not necessarily into these things,’ he says, ‘it’s just that they are part of the air that I breathe, and I like to take a picture to see what the picture will show me.’ The 10x8in camera is fundamental to his creative process.

‘The camera and its logistics lay the groundwork for the pace of the process,’ he explains. ‘It takes a lot of time and energy, but the quality, depth and credibility of the 8×10 contact print as an object transcends the picture itself. It’s like reading a novel instead of a quotation.’

His film of choice is Ilford HP5, which he processes in Rodinal developer. His prints are made on Ilford Multigrade FB Warmtone and developed in either Agfa NE or WA. He also uses Oriental Seagull paper, which he buys in from the US – and refuses to say how much it costs…

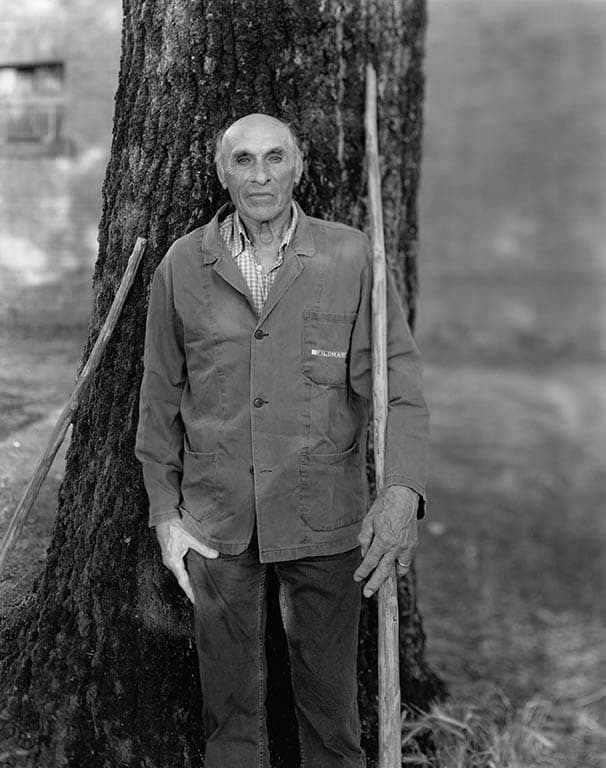

Conselice, 2018. ‘You have to be very clear that your subject needs to stay as still as the tree next to them’

A little patience

In terms of requiring both creative and technical ability, few things in photography compare to the 10x8in process. From loading the darkslides, to going through each of the steps that’s required before the shutter can be released, it’s a contemplative and methodical process.

For many large-format photographers, the most profound part of this is negotiating the ground-glass screen. The image on the ground-glass screen is inverted, but this isn’t a hindrance, as Francesco explains: ‘It means you see shapes instead of meaning. A traffic light or sign becomes a triangle or a circle or a line. It’s difficult at first, but after a while it feels completely normal.’

He also notes it’s possibly the only time when we actually see the world in the same way our retina does – before our brain turns things the right way up again. Patience is a huge part of being a large-format photographer.

Castelguelfo, 2018. Francesco has been shooting with the same camera and lens combination for 15 years

‘Shooting film forces you to wait,’ says Francesco. ‘First, you wait to take the photograph, then you wait to develop the negative, then you wait to make the print.’

Often, he will leave the prints in a pile on his desk or in a box for a couple of weeks before looking at them again and trying to come to a decision about whether or not they have been successful. ‘I am very doubtful of my own work, because I have to be the first judge of it – the first viewer – and that’s always difficult,’ he says.

But alongside patience, perseverance is also crucial. ‘Most pictures are failures,’ he states. ‘But don’t give up. You need to have faith and persevere, and be obsessed by photography. With large format, it’s about falling in love with the camera, the process and the experience of it.’

Francesco’s top tips

1) Large-format photography takes a lot of time and energy. I always say to my students that stepping outside the house is half the job done. Everything else that follows will teach you something.

2) When you look at an 8x10in contact, it’s not a print, it’s an event. Keep looking at an 8x10in and you’ll find different details you didn’t notice at the time, even years later.

3) With portraits, look for a spot to set up the camera, and frame it roughly. Then invite the person into the frame. From that moment, it’s a case of starting a negotiation between the person, the framing and the background.

4) To use a digital camera, you have to be a really well-trained film photographer. If you are to judge an image right away and be sure it works, you have to be completely in control of it, and in control of your own work.

Francesco is Professor of Photography at the Institute for Graphic Design in Faenza, Italy. He fell in love with photography while studying graphic design. In 2018 he won the first August Sander Award, and his book, Farmers, was published in 2020 (Hartmann Books, £35). See his website