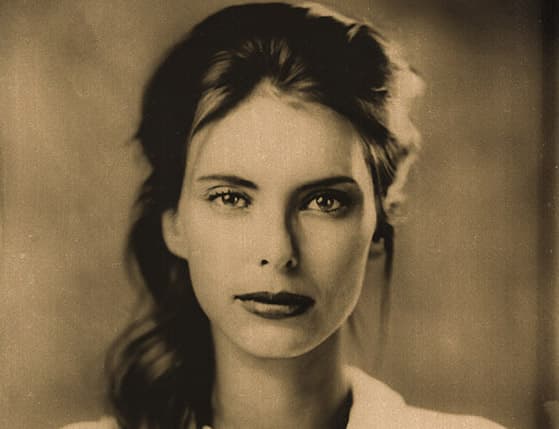

I assumed Patrick Van den Branden is a professional photographer for three reasons. The first was that his pictures are so good, the second is that he has a lot of them, and the third was that the sort of pictures he takes require an enormous investment of time and effort. I suppose reason three should have made me question my assumption, as professional photographers don’t usually have the kind of time that allows them to experiment with chemical formula or the sort of processes that involve a significant risk that the result may not be as intended – if an image appears at all.

A print made on a 10x8in glass sheet and coated to appear as different colours, depending on viewing angle

The Belgian photographer, in fact, does have a real job. Patrick works in the Belgian National Bank as a photographer for the internal staff magazine – so I was right in a way. The work he does there, however, is a thousand miles away from that which he shoots in his free time. For work he uses digital equipment to deliver results in double-quick time; in his own photography, however, time almost stands still.

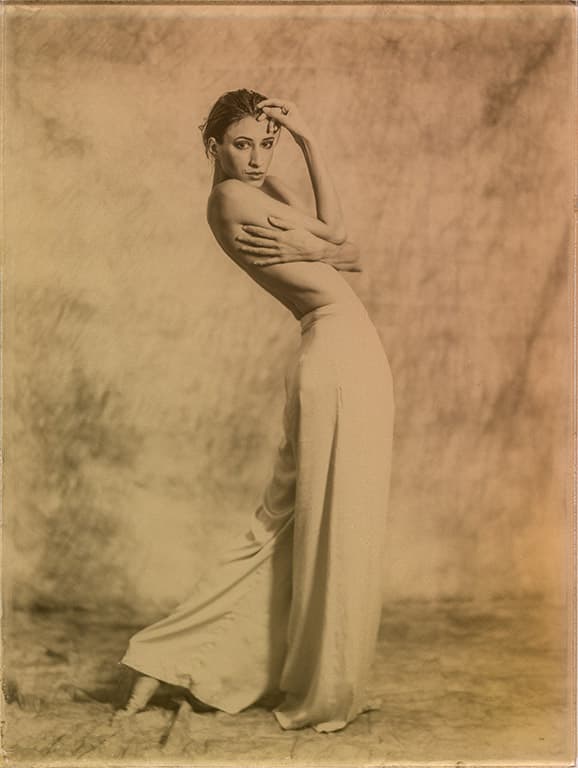

Patrick specialises in ancient forms of photography using large-format cameras, chemicals and alternative processes. Some of the pictures shown on these pages are digital in origin, but the photodiodes are used as a means to an end that involves printing techniques as old as photography itself. Other images here are shot with wet emulsion on glass, on sheet film and on photographic paper, but all were made for the love of the effects that can be achieved when you try something different and pursue something unique.

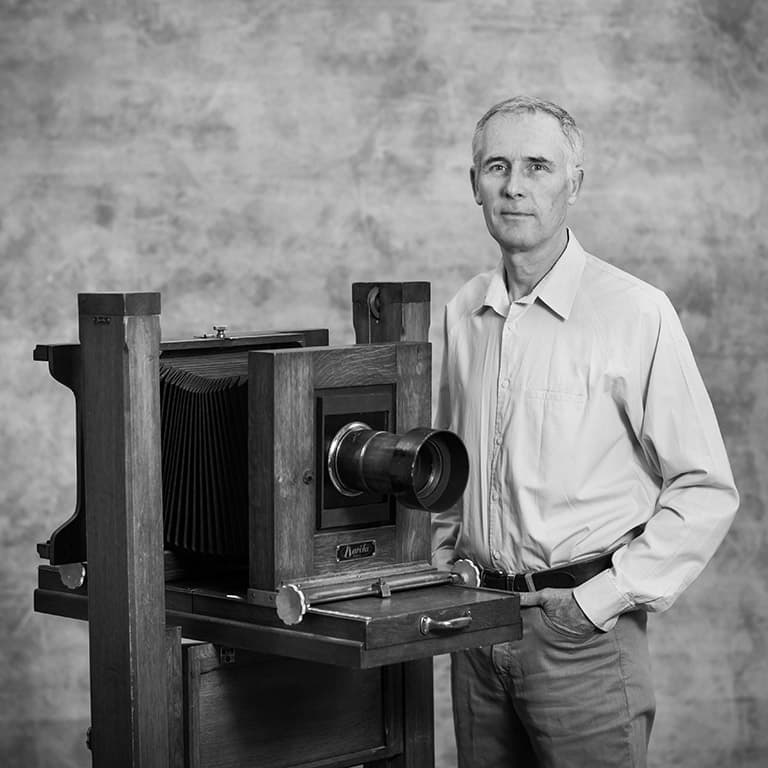

Patrick Van den Branden, pictured with his Narita studio camera

From pixels to crystals

Patrick has been a photographer for about 20 years. Starting out as an amateur shooting black & white he switched to digital photography when he got a job taking pictures for work. ‘I missed the handmade element of analogue photography though,’ he says. ‘I need to feel and to touch what I am doing, and I felt that digital photography was a bit too perfect. There’s an unpredictability with analogue photography that is exciting, but with digital it’s all numbers and you know exactly what you are going to get. I missed the magic.’

Patrick decided to branch out with his own photography and in about 2010 began shooting with large-format cameras. ‘The internet has been really helpful for learning alternative processes.’ he says. ‘Previously you had to know someone who could teach you the old techniques but now you can go online and find a world of people working this way. I go to the European Collodion Weekend – yes, that exists – every year as well, which is a great place to see other wet-platers working and to discuss techniques and processes.

‘My large-format photography is my hobby and is purely for personal pleasure. I don’t do commissions. However, I am due to retire in four years’ time and I don’t want to sit around doing nothing, so I hope to establish a school so I can pass on my skills and experience.’

A cyanotype print on a heavily textured paper which was then toned in coffee and colourised using paint

You need time

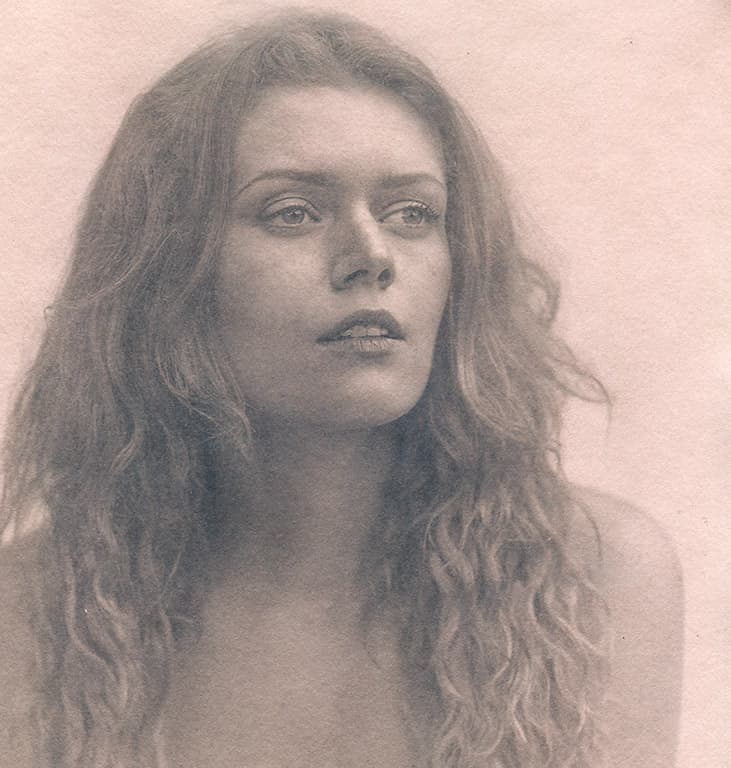

Patrick says he enjoys shooting with large-format cameras because the experience can be the opposite of that shooting with a digital camera. ‘The approach is very different when you are working with heavy, bulky cameras and lenses, and it presents another way to take pictures. It demands time and thought, and I can only make a small number of pictures in a session.

Models sometimes think I come from a different age when they see the cameras, and they are very surprised that it can take 15 minutes just to make one exposure. They also have to work differently, and have to keep still and hold their poses for longer. Maybe I can make six or seven photographs in an hour, but the models think it is fantastic when they see the results because they look so different.’

It is the size of the recording medium and the characteristics of the lenses, as well as the processes used, that create the unique look in Patrick’s pictures. ‘Large-format lenses offer more harmony in their rendering – there’s a smoother transition from focused to unfocused areas, which gives the pictures a special look and feel. I choose lenses for their characteristics and what I want to achieve in the shot. Petzval lenses create a beautiful swirl at the edges of the frame which suits some portraiture very well, but my Voigtländer Heliar is sharp from edge to edge and creates a very different look.

I have about ten lenses for my cameras – you can’t do everything with the same lens – but there are three I use all the time: the Voigtlander Heliar, a Petzval lens from before 1850 and a French Hermagis 300mm lens that has beautiful glass but a very worn brass barrel.

Narita 10x8in camera with Voigtlander Heliar 300mm lens

‘I have a collection of cameras too. My studio camera is a Narita made here in Belgium. It is built onto a wooden stand, must weigh 100kg and has a cable system for moving the camera around. It was a standard camera for portrait studios before the war, and it shoots 10x8in plates. It stays here in the studio. I have a French camera that takes the standard 10×8 Fidelity double dark slides which is a bit easier to use and move.

Magnola 5x7in camera with Trioplan 210mm lens

With ten dark slides I can shoot 20 pictures. There is also a Magnola 7x5in Czech copy of the Linhof field camera. When I am shooting friends as models I can be more relaxed and pick one camera, but if I am paying a professional model I often shoot with two cameras to try to optimise my time.

I might shoot some wet plate but also some film or paper negatives in between. Once I have a negative I can then either print that on to glass or make a print and shoot it with the wet plate camera later. This gives me plenty of options.’

You might think with the time it takes to shoot with these beasts that planning would be a big part of the success of the shoot, but Patrick doesn’t work that way. ‘I don’t usually work out what I am going to do until the model arrives. We talk and the ideas come. I try to keep things as simple as possible, and improvisation plays a big part in what I do. If we are on location in the forest I’ll get ideas from what is around me and how I feel. I am inspired by nature, but live in a city an hour away from the countryside, so I find inspiration from the trees on location or I find nature in the human body in the studio.’

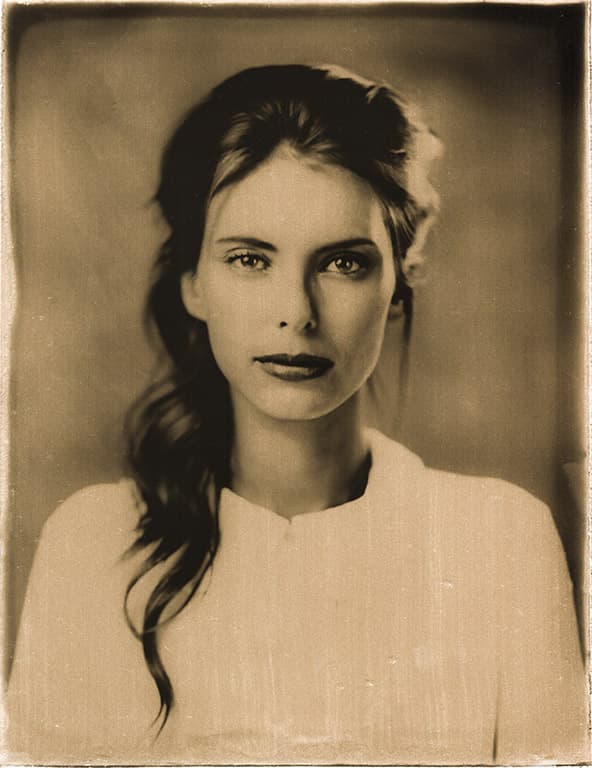

This is a wet-plate image printed onto glass with the rear side of the glass coated in orange pigment to create an ‘orotone’

Ancient and modern

Patrick likes to shoot using the ancient wet plate process that involves coating a sheet of glass in collodion, letting it dry a little and then sensitising it in a bath of silver nitrate. The sheet of glass is loaded, while still wet, into a plate holder and then taken dripping to the camera for exposure. The plate needs to be processed straight away as the image degrades very quickly, and once processed the emulsion side needs to be coated with a layer of varnish to protect it.

The end result is a large glass negative that can be used to make prints. This is usually done by making a contact print – laying the glass negative on a sheet of photographic paper and exposing the resultant sandwich to light. The process is highly unpredictable as there is a host of things that can alter the way the picture comes out – or indeed prevent it from coming out at all. ‘It is exciting that you don’t have full control of the process,’ explains Patrick.

‘You have to accept that fact and let the magic happen. The magic doesn’t happen every time though – sometimes it’s a mess and I can’t get a good picture. Then I think about the time and money this all takes and that I should just stop with the collodion. But then when the magic does happen it is so rewarding I can’t wait to do it again.

‘When you first start out and everything is new you will get amazing photographs. The problems begin a little later on when the chemicals get contaminated and you have to learn how to clean them and fix the common issues. It takes about three years to learn how to get consistent results and to understand all the variables in the process. The maturity of your collodion makes a big difference to the contrast and sensitivity of the plate.

An ambrotype print made on glass from a wet-plate original

Fresh collodion has an ISO rating of about 1 or maybe 0.5, and the contrast will be low. After a couple of weeks the ISO rises to perhaps 3-5 and contrast increases. Next the speed drops off but contrast continues to grow. I often keep a bottle of fresh collodion and an older one so I can mix them together to get the kind of contrast I’m looking for. Of course, it takes experience to know what the result will be and how much of each to mix.

Even then it is unpredictable, as every time you open the bottle some alcohol evaporates affecting the thickness of the liquid, and then there’s the temperature of the glass, the room and how long the plate sits in the holder while I give last-minute directions to the model. All these things can make a difference.’

Patrick has found that a mixture of continuous lighting and a burst of flash works well in the studio environment but he doesn’t use a light meter. ‘There’s no point,’ he explains, ‘as there are too many other changing factors. Now though I can guess that with a certain lens and the current condition of the collodion that perhaps I’ll need an exposure of 7 seconds. I shoot a test to see what it looks like and then adjust the exposure if I need to.’

Shooting isn’t confined to the studio though, as Patrick also likes to shoot outside. He mostly shoots on film or paper when away from the studio but can also shoot wet plate when he wants to. ‘I have a mobile darkroom that fits nicely in the car. It is just a dark box with arm holes really, and a red see-through plastic panel in the top so I can watch what I’m doing, but it works very well. Other wet platers use tents, but I like the compactness of my car set-up.’

Patrick’s cellar darkroom has quite the collection of different chemicals

Collodion in colour

Very few of Patrick’s pictures are presented in black & white, as most are toned or dyed somehow or other. He uses cyanotype paper to make blue prints but often tones these with coffee to get colours ranging from brown to black. He also likes orotones that are made by printing on glass and coating the back of the glass with an orange oil paint – originally banana oil was used. Coloured glass is sometimes used to print on and he has found a varnish that makes plates dichroic – showing different colours depending on the angle from which they are viewed.

A very effective technique that Patrick has come up with involves combining the wet plate process with the colour of a digitally recorded image. To do this Patrick has built a box that fits over the back of a large-format camera and replaces the ground glass screen with a sheet of plastic that has a smoother texture. His Lumix camera is mounted in the box with a 20mm lens to record the image on the sheet of plastic.

This colour file is converted to monochrome to make a black & white print that Patrick then copies using the wet plate camera. The final image is made by combining a scan of the wet plate image with the colour of the digital image. And the result is a unique and interesting picture that has the look of a wet plate but is somehow in colour.

‘It is a perfect mix of technology from today with that of 150 years ago, and is the sort of thing photographers from those early days were doing themselves – constantly experimenting and pushing things forward,’ he says.

This image was made by combining wet plate and digital photography

Materials

Patrick uses a range of light-sensitive papers, films and liquid emulsions for his work, all chosen with the benefit of his extensive experience. Rollei’s Black Magic is the liquid emulsion he uses to coat glass when he’s going to print on it.

He uses the grade 3 or the variable contrast version. When making cyanotypes he brushes his mixture on to art paper to get a textured effect, and often copies just a small section of the print to enhance that texture for the final image. Brushing the mixture onto the paper he says gives the prints a more painterly feel, and he uses different papers for different effects. He tones with coffee as already mentioned, but also sometimes adds a wash of water colour paint to alter the base colour of the paper.

‘I use Bergger Printfilm for making large-format negatives,’ Patrick tells us. I was surprised because I expected him to use regular sheet film, but he explains: ‘I use this as it behaves and handles quite like my wet plate materials. It has a very low ISO of 3 and as it is orthochromatic (not sensitive to red light) I can develop it under a safe light and see the image appearing – which is also how I work with plates. I develop this, and the plates, in Kodak Xtol fine grain developer. I like the look this gives – it is similar to D76 – but in addition it is more environmentally friendly because it is based on Vitamin C.

‘When I’m making paper negatives I use Ilford Multigrade IV. I don’t pre-flash my paper, but I do often use a yellow filter over the lens in order to reduce the contrast, which works very well outdoors. When you use 10x8in sized paper you get a lot of information.’

Stillness

There’s a stillness in Patrick’s pictures that I find relaxing and calming. It comes about through his necessary use of long exposures due to the low sensitivity of his emulsions. The world looks different when viewed through a 10-second exposure. ‘People say you can’t lie when you are being photographed in wet collodion.

You have to be yourself – no one can hold a fake smile or expression for long enough. I often use a head brace to keep my models still for the long shutter speeds they have to endure, but I’ve noticed pictures taken at 10 seconds are sharper than those shot with one-second exposures. A small movement of the eye has less impact in the long exposure and goes unnoticed. In these long exposures the attitude of the model is also very different – they have a different presence. I like that.’

I like that too, and it serves as another element that makes Patrick’s pictures look different. Long exposures are common in large-format photography, of course, but that look combined with his processes, imagination, coloration and a creative eye for a deeply emotional image is what really makes these pictures stand out in an ever more crowded photographic world.

Advice for large-format beginners

‘Start with paper negatives first so that you get to feel the magic immediately without all the problems of working with wet plate. You can buy a cheap camera, have a lot of fun and scan your negatives to make beautiful positive images. These negatives can be used to create cyanotypes as well, and as the basis of a host of other printing processes.

You only need quite simple equipment, and developing paper is easy and cheap. If it goes wrong it doesn’t matter – you can do it again. Development is also quick, so you’ll get that sense of satisfaction without having to wait too long. If you like it you can move on to wet plates later when you have a bit of practice. You can experience the magic of large-format photography and old processes without spending very much money and without it taking up too much time. And the rewards are wonderful.’