The objects we share our lives with can have a rich history that echoes our own. Tracy Calder asked photographers and repairers about the camera equipment that tugs at their heartstrings

In 1970 Don McCullin was with a platoon of Cambodian soldiers in the rice fields of Prey Veng when the Khmer Rouge opened fire. McCullin chucked his camera (a Nikon F) on a nearby ridge and hurled himself into the water, his head almost submerged. When he retrieved his camera moments later, it bore the imprint of a bullet from an AK-47.

The photographer found this exhilarating, as he explains in his autobiography Unreasonable Behaviour. ‘I thought to myself, Boy, you’ve done it again,’ he admits, ‘you’ve managed to get away with it.’ Almost 50 years later this battle-scarred Nikon was a key exhibit in an exhibition of McCullin’s work at Tate Britain.

I’ve long held the belief that objects have a biographical history that can sometimes be read in their appearance. Just as we are unavoidably shaped, marked and transformed by our experiences, so too are the objects we share our lives with. ‘Every thing has its history as every person has its own biography,’ echoes historian Asa Briggs.

Two people who obviously feel the same are photographer Mark Nixon and author (and photographer) Matthew Hranek. Nixon’s book Much Loved is a favourite of mine. It features portraits of stuffed toys that have been snuggled, squeezed and stroked until they have literally been loved to bits.

Nixon describes these toys as, ‘repositories of hugs, of fears, of hopes, of tears, of snots and smears’. They are transitional objects that ease the path from childhood to adulthood. The pictures are both celebratory and bittersweet.

Hranek, on the other hand, selected watches as his muse. In his book A Man and His Watch, he recounts stories behind much-loved timepieces, from the Omega JFK wore during his presidential inauguration to the Rolex Paul Newman received from his wife, Joanne Woodward, to mark their 25th wedding anniversary – the case bears the words ‘Drive slowly’, a reference to the motorbike accident he was involved in in 1965.

All 76 watches in the book were photographed by Stephen Lewis who used his ‘love of objects and life-long practice of observation’ to reveal the most essential qualities of each one. To the author, the photographer and the people who own these watches they are more than just objects, they have been worn on the body, close to the heart.

If proof were needed that objects have a biographical history then consider the BBC TV series The Repair Shop for a moment. Week after week people show up with objects that are in need of serious TLC: a ceramic bowl in pieces, an airman’s jacket with broken zips and weakened seams, a pump organ that hasn’t made a sound for a generation.

To anyone else these are just ‘things’, but to the people who know their stories they are hugely emotive. ‘There are compelling stories attached to each item, which range from romantic and sentimental to downright terrifying,’ says presenter Jay Blades.

With each stitch, dab of glue or turn of a screwdriver the experts entrusted with their care fall a little bit in love with each object. Going forwards, they become part of the item’s history.

All of this got me thinking about McCullin and whether there were other cameras with biographical histories. To find out, I asked a selection of photographers and camera repairers to tell me about the cameras that have tugged at their heartstrings. First up is author and expert in photographic history John Wade.

‘Some years ago, while researching Wrayflex cameras, I managed to track down one of the old directors of the Wray company,’ he recalls. ‘Arthur Penwarden was 97 years old when we met and proved to have a lifetime of invaluable memories. After we’d chatted for a while, he showed me the first Wrayflex camera, one of three pre-production prototypes.

I saw immediately that it differed slightly from the production models and I wanted it. Unfortunately, it wasn’t for sale because, he said, it held too many memories. I left him my business card and we parted company. Two years later, I received a phone call from Arthur’s daughter.

Arthur had passed away two months short of his 100th birthday and, among his goods, she had found a camera, wrapped up with my business card and a note to say it should be passed on to me. To the untrained eye, it looks like any other Wrayflex. To me, it’s among the few cameras in my collection that I will never sell.’

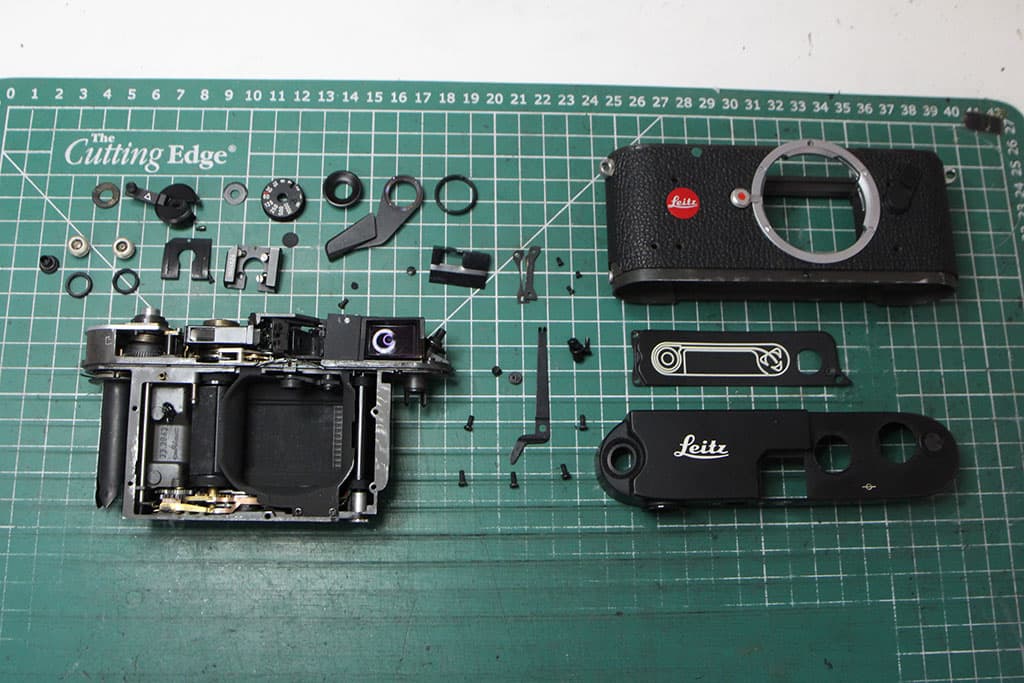

Next, I spoke to Wes Davies from Camera Repair Direct. Davies has been repairing cameras for 24 years and has a particular love for the engineering of old 35mm models. ‘We see a lot of cameras that have sentimental value,’ he says. ‘These items have often been passed down or given as a present, so I must admit that I try a little harder to get them going for our customers.

One of our customers, who recently passed away, used to bring his cameras in for a yearly service and show me the pictures he had taken from around the world. He had some great shots, and you could see how much he cared for his equipment – it was like an extension of his soul. I love to travel but I don’t get much chance these days, so I enjoy looking at pictures and hearing such stories.’

Davies is not the only one who enjoys working on analogue equipment. Philip Sendean from Sendean Cameras has a soft spot for Contax 645 cameras and the Braun Nizo 801 Super 8 Cine Camera. ‘The Nizo 801 is well engineered and was ahead of its time,’ he enthuses. ‘It should outlast its rivals.’

Sendean has heard many stories over the years and is keen to tell me about a Canon EOS 5D that crossed his path. ‘It was used for filming a documentary about walking with elephants and following their journey,’ he explains.

Meanwhile, Adrian Tang from the Camera Museum loves to get his hands on cameras from the Hasselblad V-series. ‘It’s always rewarding to keep such iconic models fully working and in good health,’ he says. ‘Once a customer brought in a Hasselblad V-series camera with a lot of sand inside and we had to dismantle and clean every part.

It was time consuming (and very expensive!) but both parties were happy in the end.’ Tang believes that almost anything can be repaired, but not everything is worth the time and money it takes. Like Tang, Steve Smart from Camserve Ltd loves to work on well-designed and manufactured models.

‘All manufacturers tend to make the odd “lemon” from time to time, but in general Canon, Hasselblad, Leica, Nikon and Rollei all make items that are serviceable for years,’ he suggests. Smart is often told about cameras that have come to a sticky end. ‘One guy left his Canon EOS 5D Mark III and zoom lens on the roof of his car and didn’t realise until he’d finished his journey,’ he remembers.

‘When he retraced his steps, he found what was left of it – it had been run over several times. Another chap suffered a heavy nosebleed at the precise moment he was cleaning his sensor, so it ended up covered in blood.’

Finally, I made contact with neuropsychologist (and former photojournalist) Dr David Lewis-Hodgson who told me about his beloved Nikon F. ‘This camera “served” with me throughout the conflict in Belfast (1969-75). It has been attached to the tailplane of a Tiger Moth, smashed (but repaired) by a Lightning fighter making an emergency landing in a gravel pit arrester and drowned in 40ft of sea water when the underwater casing flooded.

Despite being half-a-century old, it still works fine!’ Going back to McCullin, I can see why his particular Nikon F attracts so much attention. This camera has been a witness to atrocities that, thankfully, few of us have had to endure. It has served as both a physical and mental buffer for the photographer over the years.

The scars it bears can be interpreted as his own: every scratch, dent and graze tells its own story. Just like McCullin, this camera has a personal biography and its past, present and future have been shaped by war. The objects we share our lives with – from teddy bears to watches and cameras – might not have a voice, but for those who know the source of their scars they do speak.

Best UK camera repair shops

A small selection of the camera repair services offered in the UK

Aperture UK

In-house repair service for film cameras and lenses, specialising in repairs to all mechanical cameras, but especially Leica, Hasselblad, Rollei and Nikon.

What is your favourite camera to repair?

‘Nikon, Hasselblad and Leica, but especially the Nikon F2.’ Kriton Krimitsos (camera technician)

Camera Museum

Camera shop, gallery, coffee shop and in-house repair service, specialising in analogue Hasselblad, Rolleiflex, Leica, Nikon (and other similar models).

How do you approach a repair job? ‘It’s a bit like surgery: first you need to identify the problem and then you need to work out what parts you need to fix it!’ Adrian Tang (co-founder)

The Classic Camera

Rangefinder and mirrorless camera specialists offering repair options for mechanical cameras, lenses and optical devices, plus digital repairs through individual manufacturers.

Camera Repair Direct

In-house repair service, specialising in digital cameras, SLRs, compacts and lenses.

What can’t be repaired? ‘Liquid damage can be fatal. Cameras can often be brought back to life, but they can experience issues later down the line because liquid gets everywhere.’ Wes Davies (owner)

Camserve Ltd

Camera service and repair centre (90% of work carried out in-house) handling everything from analogue to digital, lenses and flash.

Are there repairs that people shouldn’t attempt at home? ‘We see quite a lot of cameras and lenses in pieces because customers have taken them apart and can’t put them back together again. The rise in “how-to” videos is partly to blame – some suggestions are plain wrong!’ Steve Smart (director and owner).

[Most digital cameras can also give you a nasty electric shock if not handled correctly.]

Fixation

In-house repair service for DSLR and mirrorless digital camera systems. Also has a professional lens repair workshop and lighting repair centre.

Sendean Cameras

Camera repair and equipment hire service, handling analogue and digital equipment (all technicians work in-house).

What are the most challenging repair jobs? ‘Some older electronic cameras are tricky because spare parts are no longer available and we have to engineer methods and make parts (sometimes using 3D printing) to keep them running.’ Philip Sendean (director)

Further reading