As a control freak I find the idea of allowing other people to decide what my pictures are about more than a little uncomfortable.

However, not everyone has the same psychotic requirement for a unified view of what their work means – Oliver Mayhall is one of those art photographers who is happy for other people to make up their own mind and have their own free-range opinions. In my head, meaning is meaning; but in Oliver’s, meaning is fluid and he embraces the fact that people will have alternative takes on his message.

Sea of Grain. Canon Sureshot A1 with Ilford HP5

‘Sometimes I get comments on my work where people have a completely different view on what it means,’ he says. ‘For me that’s really cool. I want people to make their own judgement and interpretations of meaning. That people are making up their own interpretations makes it all the more interesting.

I took a picture of my girlfriend on holiday (above) that I posted on Instagram. In the picture she’s in the sea and waving her hands above the water. It was a very funny moment. When I posted it though, during the lockdown, people were like “Wow! That really captures the moment and where we are right now – with everyone feeling like they are drowning.”

But in actuality it was a really joyous moment and we were having a lot of fun. Part of my work is about creating an abstract and whimsical world around me, which is more exciting than reality. People will always have different interpretations of an image that will be derived from their own experiences and what emotions come up when they are viewing the picture.

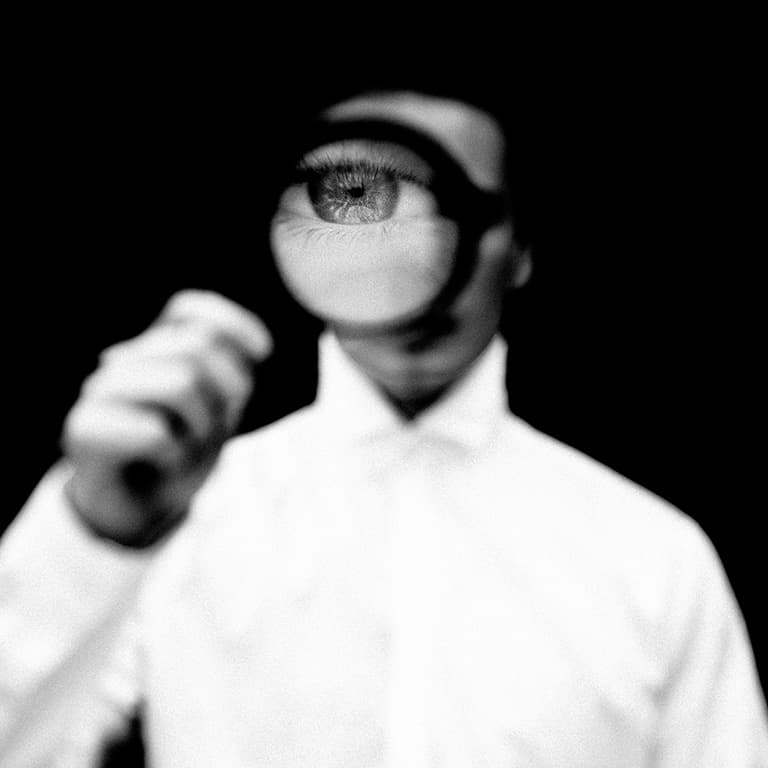

Magnified. Mamiya RZ67 with 110mm f/2.8 on Ilford HP5

I get messages sometimes when a picture really touches someone, and that’s very satisfying however it has made them feel. ‘Of course I‘ll have my own idea of what things mean and about why I shot a particular picture, but to hear that someone else’s impression of that picture is totally different is interesting. I’m not saying they are right or wrong, and I can’t stop what other people think.

And I don’t try to steer people to any conclusion with big captions that tell them what the picture means. I prefer to leave it open. I totally get why people see something else happening in the shot of my girlfriend in the sea – to me it was a joyful occasion, but to many others it looks like she’s drowning.’

‘I recently made a zine called It’s not always black and white which contains lots of my black & white work so far. The idea is you should make up your own mind about what the pictures mean, and come up with your own interpretation based on your own life experiences, feelings and emotions.

I class my work as ‘art photography’, so I can leave meanings open. In reportage and documentary you need to be as honest as you can and make meanings clear, but with abstract work it’s about generating a conversation. I don’t feel like I should be telling people what to think.

In some of my shots, like my street work, I’m photographing what’s going on around me, but others are more constructed and I’m in control of everything that’s in the frame. Just because I’m happy for people to interpret what I do in different ways doesn’t mean I don’t have some purpose or meaning in mind while I’m taking it. Some people will get what I am trying to say, while others will make their own mind up. I like that.’

Lou. Mamiya RZ67 with 110mm f/2.8 on Ilford HP5

Words are not enough

Oliver is a young London-based photographer who makes his living shooting commercial portraits. Most of his work comes from clients contacting him via Instagram, he says, and he supplements this income by selling fine-art prints and zines of his personal work – again with most of his buyers coming from his Instagram page.

‘The more active I am on Instagram the more prints I sell, so posting new work brings people to my site. That’s the direction in which I really want to go,’ he says, ‘selling prints of my fine art work.’

He loves to use film for his personal work and whenever he can in his commercial commissions. As is so often the case with photographers who shoot on film, Oliver finds it hard to put into words what it is about silver halides suspended in gelatine that attracts him.

He has been shooting this way for about three years, after being inspired by other photographers’ images.

‘I’d been admiring pictures online shot with medium format cameras and I was really drawn to the look so I bought myself a Mamiya RZ67 to experiment with,’ he explains. ‘There’s much more character and warmth in pictures taken on film, and it’s a look that’s very hard to replicate with digital photography.

I mainly shoot medium format and that, along with the film, gives a sense of depth that you can’t get with a regular digital camera.’

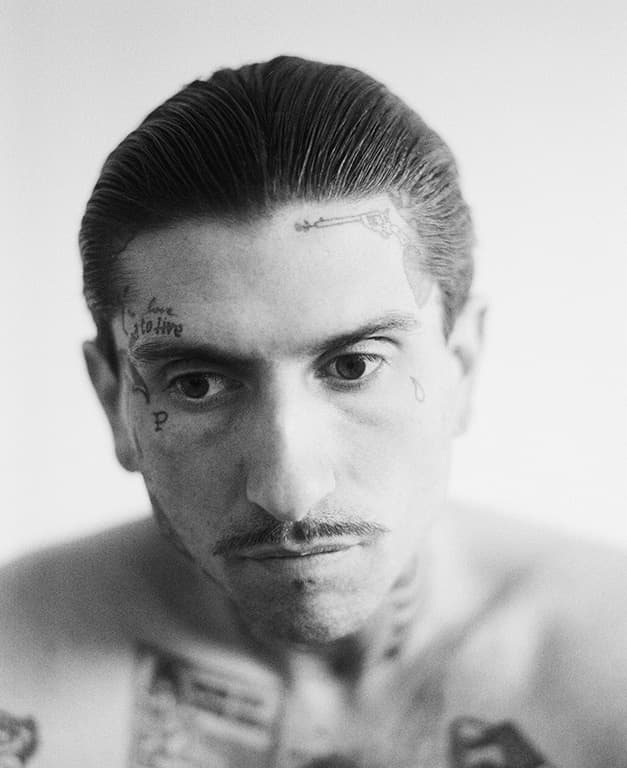

Gus. Mamiya RZ67 with 110mm f/2.8 on Ilford FP4

For his commercial work Oliver uses a Canon EOS 5D IV digital SLR. He says this is for safety. Once he is happy he has the shots he needs, he gets the Mamiya out to do the pictures he enjoys.

‘Getting the shots on the digital camera first allows me to relax and know that I have the shot already, but then I can I go on to shoot on film. That’s when the fun starts.

The Canon camera is very good but it doesn’t excite me at all – it’s just a tool that gets a job done. The Mamiya I love using. I love the feel of it, and the sound of it. It makes me slow down and makes me shoot in a more considered way. I think carefully about the pictures I shoot with the Canon of course, but working with a digital camera I can become a bit trigger-happy.

When you only have ten shots on a roll of film you tend to be more careful about when you press the shutter button. I’ll move the camera fractionally from one side to the other, and make tiny changes to the composition, before taking the picture, to make sure it’s right. That process renders better results.

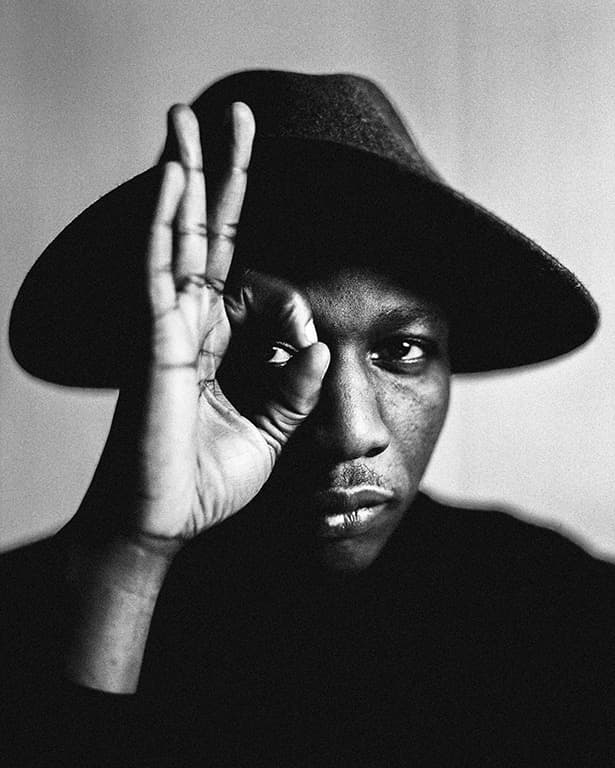

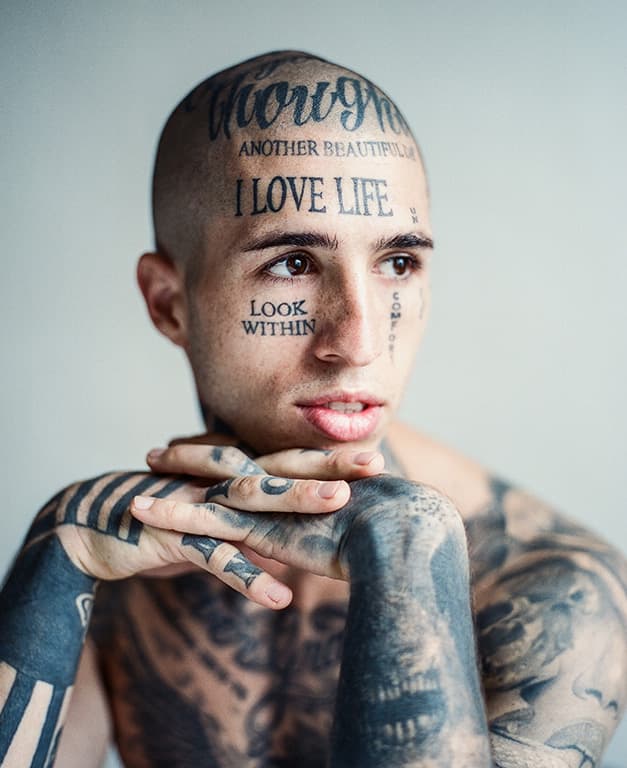

Emmanuel. Mamiya RZ67 with 110mm f/2.8 on Ilford HP5

With digital cameras I tend to shoot and check after that it looks good. I shoot on film whenever I can for a commercial job, and sometimes I actually get commissioned specifically to produce film images – which is really nice.

I want to shoot more on film as I get a lot more enjoyment out of it, but also I think the pictures look so much better.

When I get scans back from the lab nine times out of ten – actually ten times out of ten – I will prefer them over the digital shots, and they will be the pictures that get used. The Mamiya RZ67 brings a sense of calm, and that shows in the results.

It’s not just because I have an emotional attachment to the Mamiya and to film, or that I might be biased with comparing the digital and film images – it’s the look and feel of the film pictures that is like nothing else.

I also like time between shooting and editing so I can look at the shots with fresh eyes. With digital shots I get to see them straight away and make a judgement on them immediately, without having that break away from them. That space helps me see my work differently.

Recently someone asked me for some files from a digital shoot I did a while ago and when I got them out and looked at them I thought, “That’s a horrible edit! I don’t know how I’ve done that.”

Ellen. Rolleiflex 3.5F on Ilford HP5

I had to reset the adjustments and start again, this time adding only a little bit of contrast – which is all it needed in the first place. Going back to work well after it was shot can help us to look at what we’ve done in a more detected way,’ he discloses.

‘Shooting film really does make me feel something else. It’s a real joy, even the feel and sound of the cameras makes me feel good. The whole process is slower too, even when I’m shooting street photography.

The aspect ratio of the format is an attraction too. I’ve shot a lot of 6×7, but now I’m trying 6×6 and find it fresh and exciting. I’m not sure if it’s just because it’s new to me. I know I could shoot in any format and crop it to 6×6 but I want to compose everything in the moment, not later on.’

Eyes abstraction

There’s a distinct abstract and surrealist feel to a lot of Oliver’s work that reminds me of the art movements popular in 1930’s Berlin, though when I mentioned that to him he said he would have to look that up as he isn’t familiar with that period.

He uses broken mirrors to reflect and lenses to magnify parts of the subject, and uses strong graphic lines and shapes to create really striking pictures.

He also has a bit of a thing for eyes that reminds me of Dali. ‘It sounds clichéd to say that eyes are the windows to the soul, but there is something in the eyes that draw me in to a subject. Eye contact is powerful. There is intensity in eye contact, and using lenses and mirrors can amplify that connection.’

I note that Oliver gets very close with his portraits, and he says he hasn’t noticed before. ‘I’m not sure why I get so close, but I suppose it’s because I like to be up close and personal. It makes the viewer feel close to the person, as though you are right there with that person.

‘I’ve always had an abstract element in my photography. When I was young I had a book of pictures of reflections in puddles, and that really inspired me. When I started taking pictures myself it was reflections and distortions I was drawn to, and I still love shooting them today. I like an abstract view – I find it stimulating to create other-worldly alternative realities. I use this abstraction and surrealism in my commercial work too.

Photography continues to be my hobby as well as my job, and I’m still trying to find a balance – I don’t always know where the line is between them.’

These are the film cameras Oliver uses most often, but he has a box of point and shoot models he takes out on occasion

Film

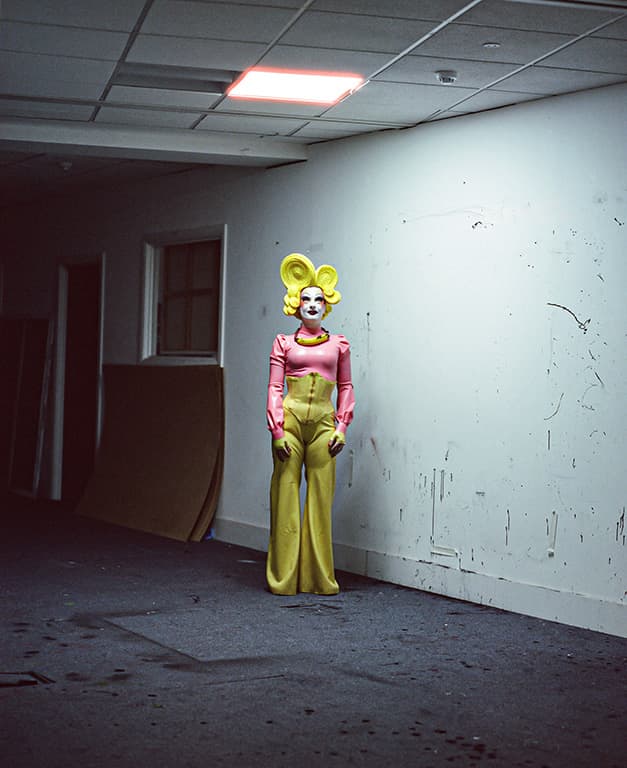

A lot of Oliver’s pictures are in black & white, but he also has a significant body of work that’s in colour. ‘It depends on the subject,’ he tells me. ‘I shot a series recently of the performance artist Marnie Scarlet who dresses in these wonderful colourful outfits, so obviously I needed to shoot that in colour – although I did shoot her in black & white too!

The black & white shots came out really well actually. For the colour pictures I used CineStill film. I do sometimes shoot digitally and try to make it look like film, but I don’t like doing it – it’s very hard to emulate the look of film. Occasionally I might add a bit of grain to a digital picture, but I don’t think you can replicate that look – it also feels quite dishonest.

‘I use lots of different films as I like experimenting. Most often it’s Kodak Portra 400 and 800 or 160, and Ilford HP5 and FP4, as well as Kodak’s Tri-X. CineStill film is my guilty pleasure as it’s so cinematic, experimental and fun to use. I want to use it for a series of night shots I’m working on.

Marnie. Mamiya RZ67 with 110mm f/2.8 on CineStill 800T

I use my film at the standard ISO rating, except Portra 400 which I sometimes rate at 200. ‘I tried processing film myself and it mostly went well, but sometimes it didn’t and I got worried I was going to ruin my shots, so I use a lab now.

want to do a course in processing, but for now send off to different labs to try them out. I’ve recently used Take it Easy in Leeds and AG Photo Lab, but commercial work always goes to Bayeux in London.’

Gear

Oliver shoots with a mixture of cameras and formats, but his main kit is a Mamiya RZ67 with the 110mm and 55mm lenses. ‘I used to have a Pentax 67 with the 105mm, which I bought because I thought it would be more portable and lightweight than the Mamiya, but it was really heavy.

Now I use the Mamiya for most of my work, and have been building the kit with the prism finder and the grip. I’ve borrowed a Hasselblad 500CM from another photographer via the Fat Llama rental site and am trying it out with a view to getting my own.

I love that it’s so small and light. I’m also looking at the Intrepid 5x4in cameras! ‘I don’t really need any more cameras, that’s for sure, but they are “toys” I want to enjoy.

I don’t think having a Hasselblad will really change anything – it’s just pure desire and enjoyment. I also have a Canon A-1, a Minolta X-700 and a box of 35mm point and shoot cameras that I occasionally pick up and take out with me. I’m not massively technical and I don’t get too over the top with specifications, I just have found things that work for me.’

Cat. Mamiya RZ67, 110mm on CineStill 800T

Oliver’s top tips for new film users

* Just keep experimenting and know that failing and making mistakes is all part of the process.

* Don’t be discouraged when things go wrong.

* Practice makes perfect.

* And enjoy it – that’s really important.’