Every six months, on the summer or winter solstice, Robert Charles Mann makes the 500-mile journey from his home in France’s Loire Valley to Château Miraval, Brad Pitt’s wine estate in the south of the country. ‘It’s a magnificent place,’ says Mann. ‘I’ve known Brad for some time. It’s always a real pleasure to be there.’

Six months in a single frame

Mann isn’t there simply to guzzle rosé with his friend, but to check in on the pinhole cameras that he set up six months beforehand, removing the negatives and mounting new cameras. ‘I never know what’s coming,’ he says, describing the anticipation of seeing what the cameras have produced each time. ‘The waiting, the appreciation, the anxiousness of seeing the images, and whether I’ve failed or not, it’s a big part of my life.’

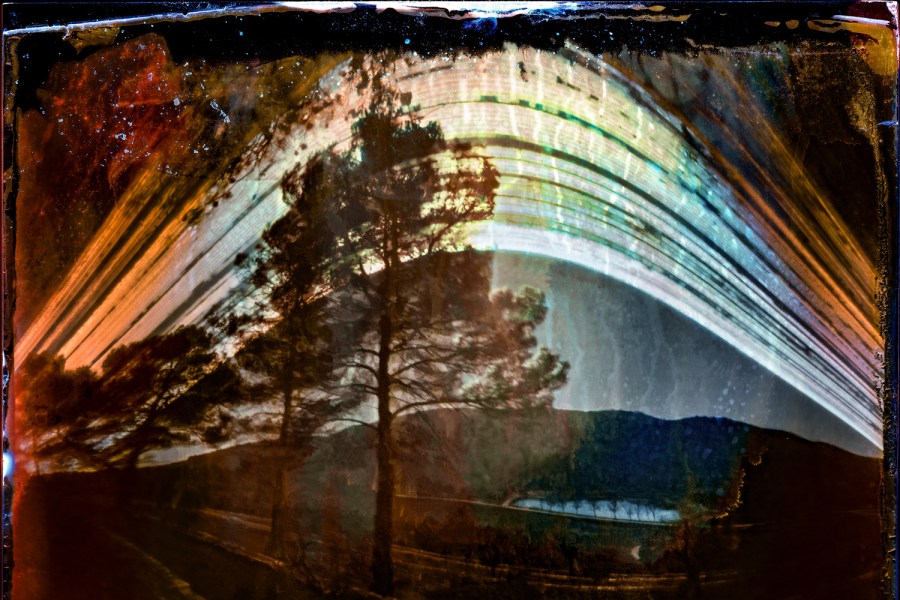

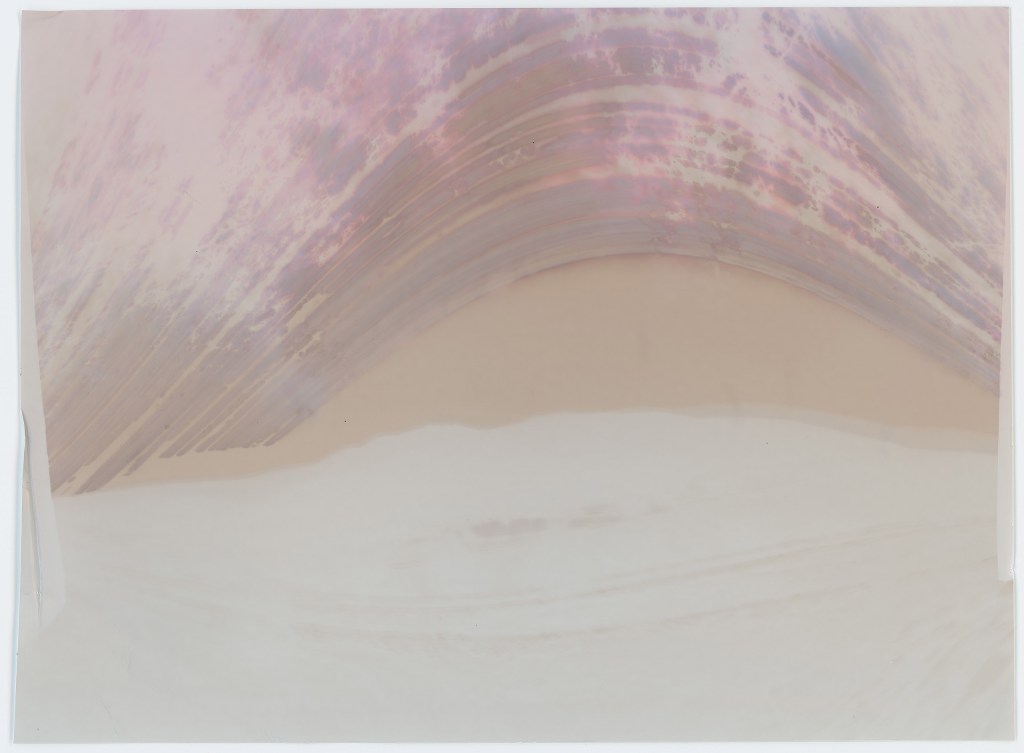

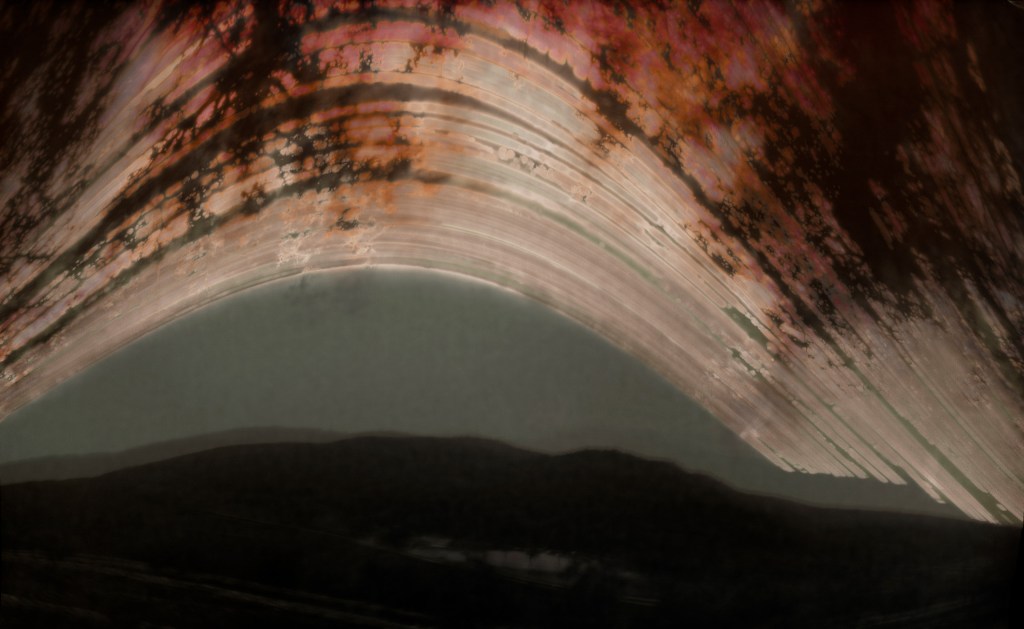

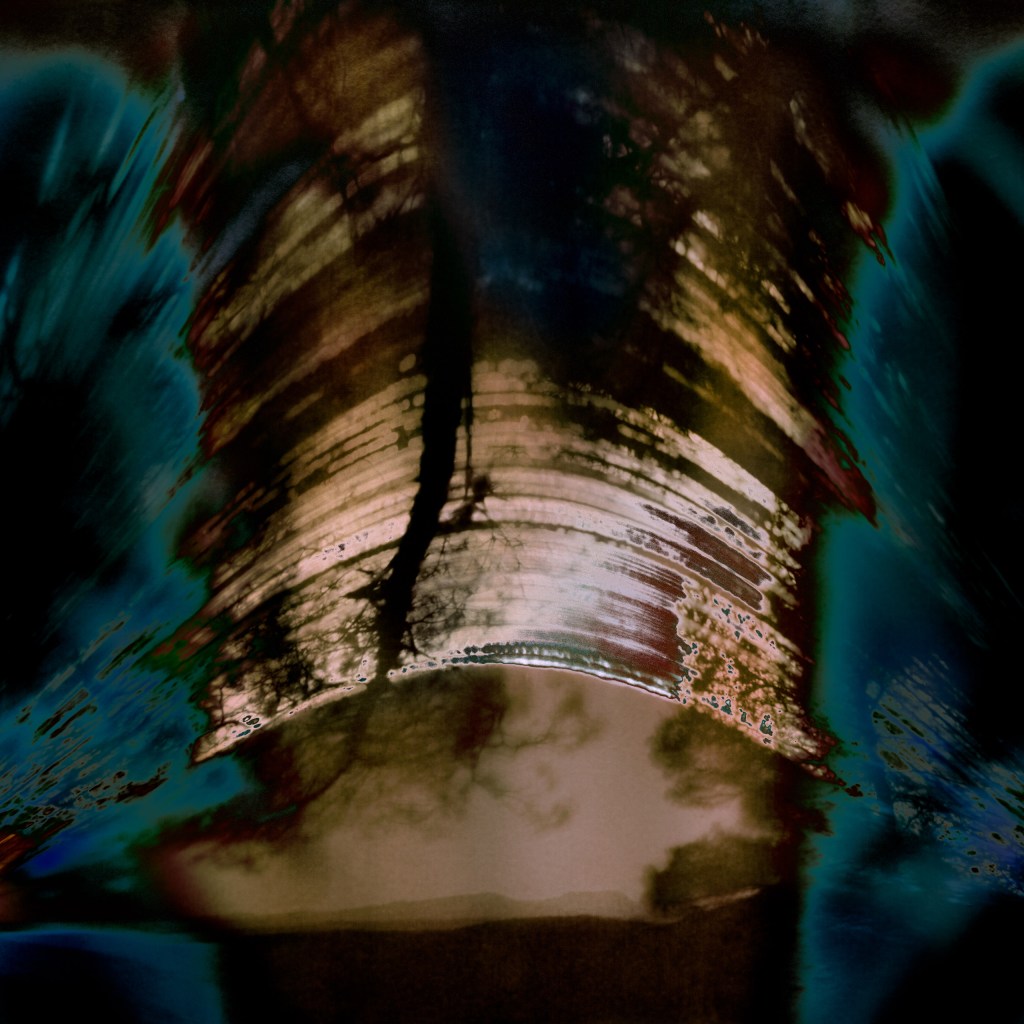

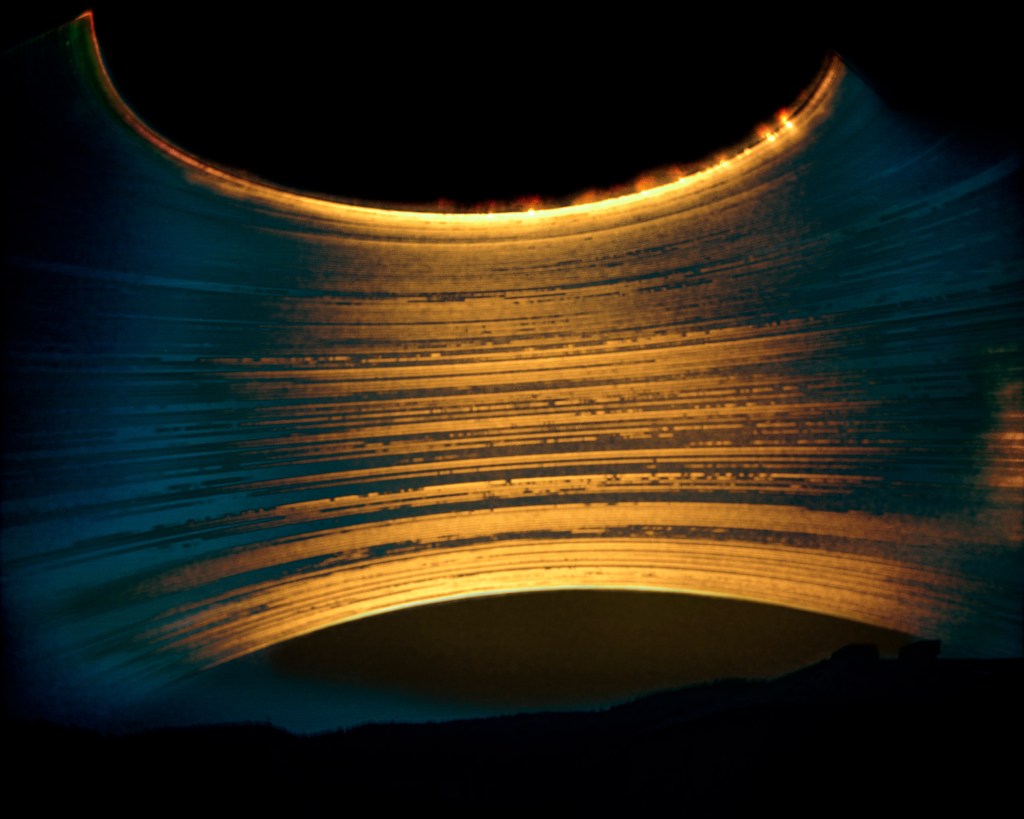

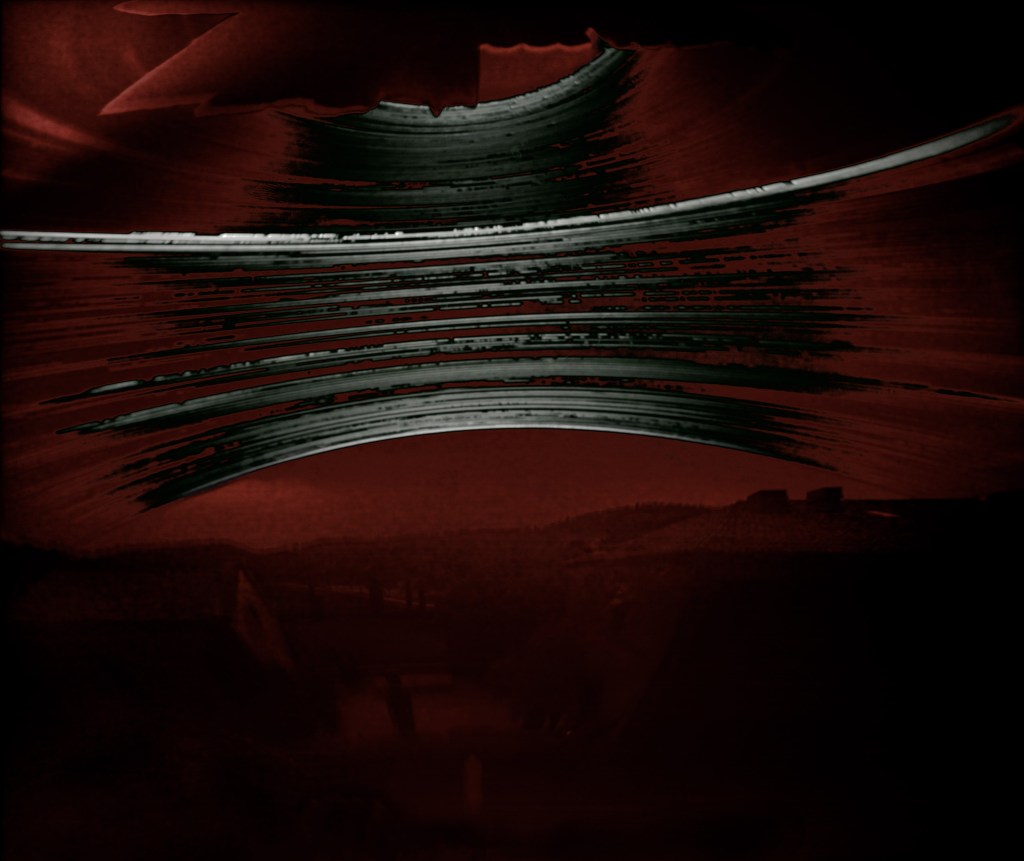

50 of Mann’s mysterious, dreamlike works from Château Miraval are collected together in his new book Solargraphs. A solargraph is a photographic image created with pinhole cameras using long exposures that capture the sun’s movement across the sky for periods of time, in Mann’s case six months.

Coffee cans to cosmic art

Pinhole cameras are a low-tech idea – anyone could build one. Mann makes many of his from coffee cans or round whisky bottle containers, though his pinholes (around 0.5mm) are produced using a laser for precise control over the aperture. But the simple camera process is combined with high end, digital production techniques. ‘When I harvest the cameras on the solstice, bring them back to the studio and take the paper out, it goes straight on the scanner,’ Mann explains. ‘I scan the paper at 400MB – big files – because sometimes I do prints of up to three metres. It goes into Photoshop and I start working, maybe some cropping… There’s quite a lot of spotting and retouching to do. Often, there’s water damage in the camera, which I leave, but I take out some of the dust or other stuff going on.’

‘In Photoshop, I spend a lot of time discovering what’s there,’ he adds. ‘The paper I use inside the camera for the negative is silver-coated black and white paper. The colours come from the nature of the silver halide formulas of different brands of paper. That’s all in the negative. If you zoom into the paths of the sun, you can see the multitude of colours available, albeit subtle. Silver has a lot of colour in it inherently.’

Hidden cameras at Château Miraval

Mann’s been producing solargraphs at Château Miraval for a decade, working with as many as 12 cameras at a time, each mounted at a different location. The images sometimes bring in tree branches, the curves of hills or other landscape features, as well as the all-important sun. ‘When I’m mounting the cameras, I have an approximation of where the sun’s going to be in the sky, just by using a compass, and where I am in latitude,’ Mann says. ‘Sometimes the cans are mounted horizontally, sometimes vertically. They give very different images based on the way the curvature of the can works. The ones that contract towards the edges are vertical, the ones that expand are horizontally mounted.’

Whereas most photography freezes a moment, Manns’ solargraphs capture six months of time in a specific place. ‘It’s about my appreciation of the sun and the cosmos, and a homage to the passing of time,’ he says. ‘I’ve studied astronomy and astrophysics most of my life as a closet scientist. Things that are ephemeral – birds flying, people walking past… – all that is actually there somewhere, maybe in one molecule of the silver. Of course, you don’t see that. But all those experiences and each day of the sun passing is all in there. The other thing I like is seeing where the sun was on each day. There are 182 passes of the sun in each solargraph. You can also determine if it was a cloudy day, if the lines are broken.’

‘Sometimes the solargraphs become link ink blots,’ he continues. ‘People walk up to these images and don’t know I’m the creator. I hear them talking – it provokes a story about a person in their life, or they can see something in there. I love that.’

Low tech simplicity

The old school cameras and slow, patient process goes against the current trend for high tech digital cameras and instant gratification. Mann also enjoys the experimentation, an approach he also utilises in making music – he’s worked on soundtracks for adverts, TV and film, including some of the music featured in Brad Pitt’s film Ad Astra. ‘It’s all to do with ‘generative music’ and ‘generative photography’.

These cameras live in nature for six months. They get shit on by birds, they get moved, they get rained on and there’s water inside. All that is part of their life. With the generative process in music, I’m setting things up on a modular synthesiser and putting things in place that will ultimately change other things down the line – something will happen, despite my own interaction with it. It’s the same with solargraphs – I can guide it in a certain way but then it has its own life.’

As with any trial and error, it doesn’t always work out. ‘Earlier on, there was a higher failure rate,’ Mann says. ‘But now I’ve learnt my lessons. I know how to seal the cans much better, which helps with potential water damage. I’ve also learnt more about also how to place them and fix them to things. I’ve discovered a lot about different types of glue and wire.’

Boyhood infatuation

Born in Wisconsin in 1960, Mann was interested in the sun and photography from an early age. ‘As a child, I remember watching the eclipse with my dad and brother,’ he tells me. ‘We had a big piece of cardboard with a pinhole in it – hooked it up and looked at all the eclipses on the ground. We also did shoebox cameras at school. My dad had a dark room in the house – he was a photographer, doing wedding photography and that kind of thing. I started printing his negatives when I was eight years old – understood the whole process before I even took a photograph. I was under the red and yellow lights with my brother, printing negatives. That’s where the fascination became an infatuation. Boy, when I picked up the camera, I was, like, “Oh, this is what’s happening!”’

In 1979, Mann moved to Hollywood to study music, composition and performance. He used his darkroom experience and printing knowledge to support himself, making prints for the Photo Impact lab and then freelance in Los Angeles, New York and Paris. Over the next 30 years, he became the go-to expert for acclaimed photographers, including Helmut Newton, Mary Ellen Mark, Dennis Hopper, Peter Lindbergh and Herb Ritts, among many others.

Hollywood friendship forged in the darkroom

It was his reputation as a master printer that connected him with Pitt, who wrote the foreword for Solargraphs. ‘Brad’s an autodidact polymath,’ says Mann. ‘He’s an architect, he builds furniture, all kinds of things, and photography is one of the things in his palette as a creator, black and white specifically. He was accumulating a lot of negatives – mainly photos of family.

Around 2005, he started looking for a printer, not just a master printer but someone he could trust, so he contacted the Herb Ritz Foundation, and I used to work with them. He spoke to the CEO Mark McKenna and said “I’m looking for someone to take on this project”, and Mark suggested me. Brad called, and after that we got on like a house on fire. We’ve spent a lot of time in the darkroom together – weeks and months on end sometimes. We did several different projects together. The first was for W magazine, when he was still with Angie. It was a beautiful story: Angie and photos of the children. It was a different time, of course. And we went from there. He wanted to keep printing. We’d print in LA or in Paris.’

A decade of decisions

Mann went on to introduce Pitt to his solargraphy. ‘I first set up cameras at Brad’s place in LA, around 2013 or 2014. He has a little place up the coast in California where I did some solargraphs. He got really into the idea of having a recording of the sun going over his properties from different points of the planet. I suggested, Hey, lets do Château Miraval, with no idea that it would blossom into a book 10 years later. I just wanted to do a few and see how it goes.’

The two men share an interest in time and metaphysics. ‘Brad’s totally fascinated with it. He enjoys supporting artists he knows and artists he appreciates. We also speak about the more difficult metaphysical question of what these images really are. He loves the idea that all these events on photographic paper, made in handmade pinhole cameras, are all from his ‘spots’ on the Earth.’

Bearing fruit

On Mann’s website, there are many other kinds of images, from portraits to landscapes, created using pinhole cameras. He’s also been working as artist-in-residence at Château de Chambord, the largest château in the Loire Valley, producing solargraphs with 45 pinhole cameras, the results of which will run as an exhibition there from March, 2026. ‘I’m really excited,’ he says. ‘It’s the first time I’ve really incorporated architecture, so there’s a lot of strange morphing of the towers. I was up at the top of the towers, mounting cameras on the highest places on Chambord. I was enjoying the hell out of it.’

He’s not finished with pinhole cameras yet. ‘I’ve got some ideas for different shapes of cans and boxes and objects, and doing multiple holes in the cans,’ he tells me. ‘I’m going to try the cameras with a double pinhole – the pinhole will be as close as possible, without breaking the actual substrate, which is a very thin piece of stainless steel, in order to get the interference patterns. I’ll work on double pinhole experiments and perhaps pinholes from opposite sides of the camera.’

With each new approach, does he have a sense of what the results will look like. ‘No,’ he says with a smile. ‘But it’ll be very strange.’

Solargraphs by Robert Charles Mann, with a foreword by Brad Pitt, is published November 18 (£50) by Hemeria available to order here

See robertcharlesmann.com and Instagram @robertcharlesmann