The iconic instant photography brand Polaroid has been reborn in Europe. Steve Fairclough discovers the story of the rise and fall of the company

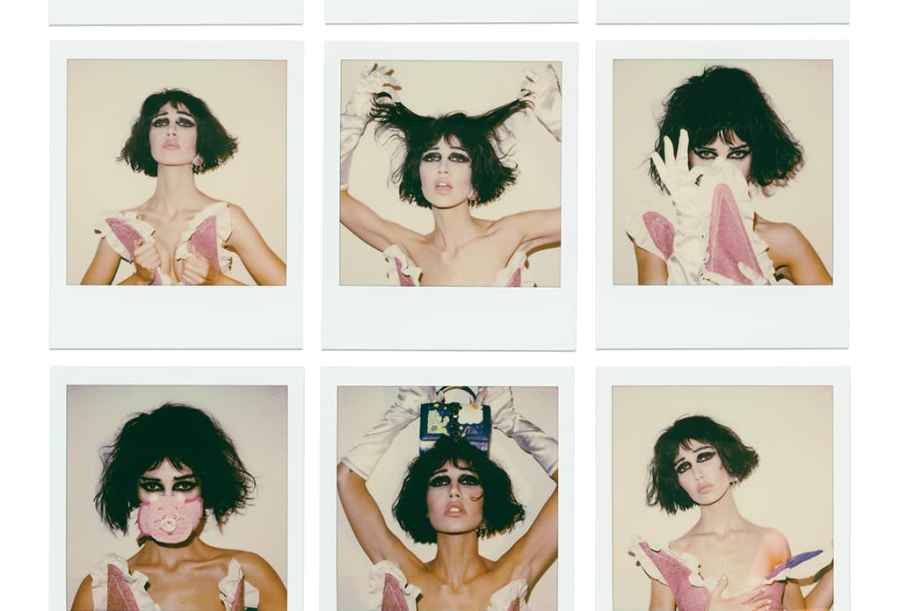

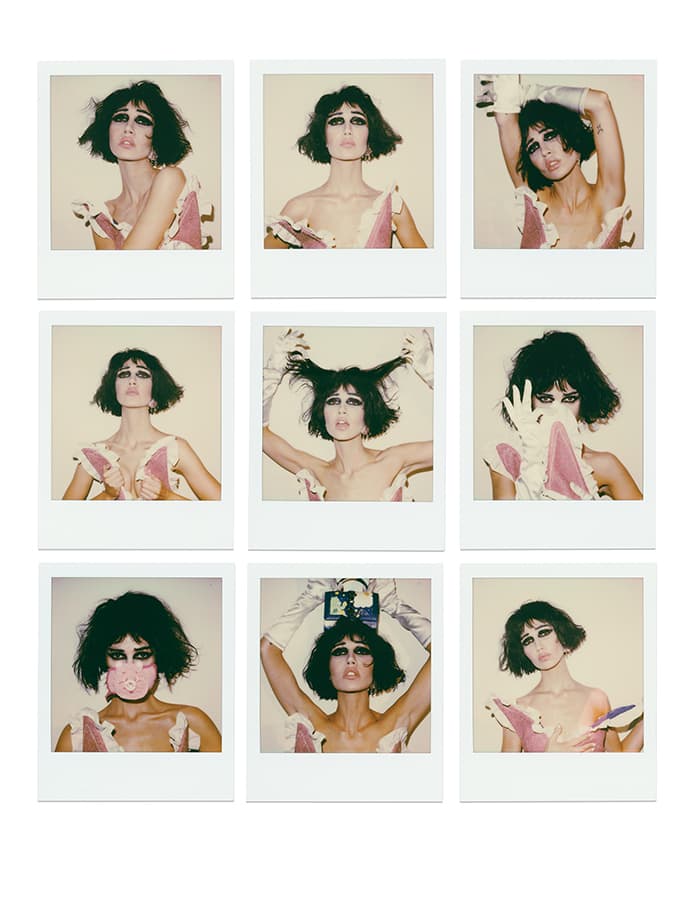

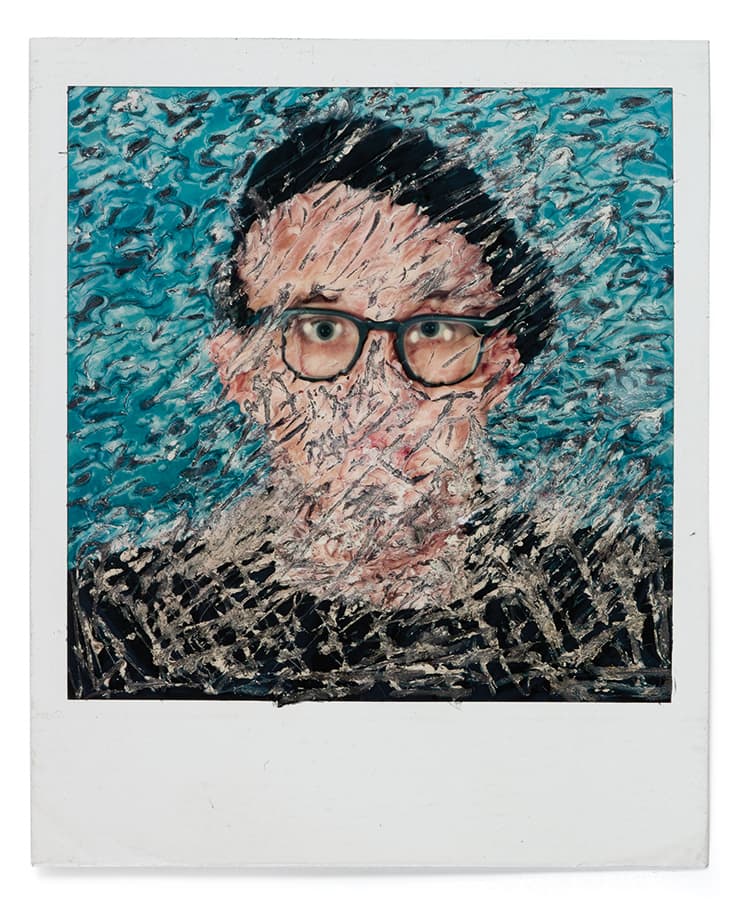

At one time Polaroid was the epitome of cool in the photography and art worlds. Andy Warhol produced Polaroid pop art, David Hockney shot stunning composites and photographers such as Walker Evans, Helmut Newton, Ansel Adams and William Wegman embraced the creative possibilities offered by the instant analogue imaging system.

What began in 1937 as the Polaroid Corporation (as a company that produced polarised sunglasses), hit a revenue peak of $3 billion by 1991 but was declared bankrupt just ten years later, in October 2001.

That early 21st century company crash was a far cry from the 1960s and ’70s when generations of photo enthusiasts flocked to buy the stylish Polaroid cameras that spewed out instant film results. Initially the film was a peel-apart product and then, from 1972 onwards, with the launch of the legendary SX-70 folding camera, as a ‘hold in your hand’ instant film that developed in front of your eyes.

Largely thanks to the drive and innovative genius of co-founder Edwin H Land, the magic of instant imaging captured the imaginations of millions, but the Polaroid Corporation was in dire straits in the 1990s and wouldn’t survive in its original form.

Following the 2001 bankruptcy – which is often put down to a failure to keep up with digital photo technology, despite the fact that Polaroid did make digital cameras – Polaroid was sold off to Bank One’s One Equity Partners. Without getting into complicated legal or financial detail… the original Polaroid was dead.

The legendary, folding SX-70 SLR camera was produced by the Polaroid Corporation between 1972 and 1981 – this is the silver and brown version

However, the tale didn’t end there and today a new Polaroid has emerged, thanks largely to the efforts of a few diehards who, in 2008, founded the aptly named The Impossible Project in The Netherlands. The story of the evolution of The Impossible Project, and those involved in it, is told in the recently published book, Polaroid Now, which is notably subtitled The History and Future of Polaroid Photography.

It’s a mixture of pictorial and camera nostalgia but is also an introduction to a fresh generation of creative talent, which is experimenting with Polaroids in similar ways to how Warhol, Hockney, Keith Haring, design company Hipgnosis and many others experimented decades earlier.

With a cover that features the iconic 1960s Polaroid packaging, designed by long-time Polaroid collaborator Paul Giambarba, the title has been compiled and edited by photographer and author Steve Crist, who has worked closely with various incarnations of Polaroid since 2004.

The Polaroid Sun 660 Autofocus was launched in 1981. Via its gold ring it pushed out high-frequency sound waves, to help work out where the subject was and adjust the focus

Collection auctioned off

Crist explains, ‘From the early ’90s Polaroid was struggling and that was in the pre-digital days. For the first book I did, The Polaroid Book, I went to the old Polaroid Corporation in Waltham, Massachusetts.

That book was an overview of the Polaroid Collection, which was the US and European collections that Polaroid had amassed for many decades. It was about photography that had already been shot, archived and was thoughtfully selected.’

Edwin Land had brought in Ansel Adams as a consultant on the US collection – a role that Adams retained for 35 years – and the company also gave access to its 20x24in Polaroid camera studio and sometimes allowed the cameras to be borrowed by a select few photographers.

A parallel collection in Europe saw some of the Polaroid work of David Bailey, Sarah Moon, Helmut Newton and Josef Sudek being bought. Polaroid went through a series of a couple of bankruptcies and Crist explains, ‘They sold the company a few times, took the great Polaroid Collection and auctioned it all off at Christie’s, so that disappeared.

But, I met Oskar Smolokowski (the current CEO of Polaroid) and he has renovated the new Polaroid. As of last year, pre-pandemic, the company is owned wholly by Polaroid BV, which is now in Amsterdam. They make the film in Enschede and it’s kind of a European/EU product, with some Chinese components, and, of course, the cameras.’

Prior to the demise of the original Polaroid the company had taken many twists and turns, but perhaps more astonishing than the technology involved in the company’s products was the way it was resurrected. To rewind a tad, The Impossible Project began in 2008 in the wake of Polaroid’s announcement that it was to cease producing film for Polaroid cameras.

The founders of the project – Florian Kaps, André Bosman and Marwan Saba – bought production machinery from Polaroid for $3.1 million, just days before it was due to be scrapped, and leased a building that was formerly part of the Polaroid plant in Enschede, Netherlands.

In what was known as the Noord Building, in 2010 The Impossible Project began producing colour and black & white films for the Polaroid Corporation’s SX-70 and 600 cameras as well as the i-Type (600 cameras with a rechargeable battery) cameras from the latest incarnation of the Polaroid company.

Also produced in Enschede were Image/Spectra films and 8×10 films. The new 8×10 films differed from the original 8×10 films because they are integral (non-peel apart) films with the positive and negative kept together.

The Impossible Project evolves

In 2012 The Impossible Project announced it would launch a range of collectable products, called The Polaroid Classic range, from different periods in the company’s history. Then, in December 2014, Oskar Smolokowski was announced as CEO – a position he still holds.

In the Polaroid Now book Smolokowski explains, ‘We all knew from day one that the mission was to reunite with Polaroid – after all, we were making Polaroid film! In September 2017, on Polaroid’s 80th birthday, we launched Polaroid Originals.

We managed to put the pieces back together and reached a deal to reunite the factory and the brand under one roof and ownership.’ In March 2020 the company became, simply, Polaroid again.

Steve Crist reveals, ‘I know it wasn’t just Oskar Smolokowski. He’s quick to point out that there were a lot of other people who helped with The Impossible Project in their early days. But I think that’s a good and apt title for it because it was like a ragtag group of people who thought that they could resuscitate an industrial scale plant.

‘Polaroid, when it died, was a large operation with many thousands of people. In the US it had tens of thousands of employees and it seems that five or ten people, whoever was in the initial group, could just grab a hold of some of the equipment and do it with a little bit of help from one or two retired people… that was pretty amazing.

That shows they saw a business opportunity but I think it’s more like a love of the material and the craft – they didn’t want to see it die. That resuscitation of Polaroid took people to save that company because of the physical nature of the manufacturing.’

Included in that era of saving products were John Reuter’s efforts to save the 20×24 Project, which had produced significant works such as William Wegman’s 1987 image ‘Roller Rover’ and Mary Ellen Mark’s black & white portraits for The New Yorker.

Reuter had run the 20×24 Project for many years and Steve Crist explains, ‘He saved all the materials from destruction. He has, in storage, some thousands of frozen sheets of the original, last batches of 20×24 film that he runs. They were just going to toss it out and destroy it, so he [Reuter] had to jump in, start a company and do that, which he has done for many years.’

The past and the future

With a current line-up of cameras that includes the Polaroid Now Plus, the OneStep+ and the Go, alongside variations of the classic 600 and SX-70 models the new Polaroid has its toes dipped in both the past and the future. Steve Crist explains, ‘I’m shining the spotlight on the Polaroid community by doing the book.

The story is the community of mostly young people and some older people who have rediscovered Polaroid and are shooting adventurously now. They’re all scanning it and posting it online, so that’s the process of sharing. They have these Polaroid get-togethers where they all meet up, hit a pub, go out and take pictures, which is funny but cool.’

Crist is also full of nostalgia. ‘I loved the old Polaroid materials that are no longer made…. the 4×5 format stuff, the peel-apart films that had the negative attached – the 59 and the 58, all those kinds of films that no longer exist. I liked the immediacy of the SX-70 – there’s something really beautiful about that material, more specifically the SX-70 than the 600 series.

I liked the look of that stuff. It provided a magenta, cyan and black value system that you saw the world through. The SX-70 provided that kind of 1970s and 1980s colour balance look that was cool.’

He adds, ‘Polaroid is a really unique company. It’s one of the few product companies I can think of, other than Apple in its heyday, that has such a dedicated fan-base that people are willing to wear clothes with the logo and graphic on it and also celebrate it by kind of loving it. We follow people who have a fan-base and Polaroid has a lot of fans.

It’s a strange firm in a sense that although it makes products, people like the outcome of the product. They love what they can do with the product because it allows them to express themselves creatively. I can’t think of another product that’s quite like it.’

Polaroid camera landmarks

1948 The Polaroid Land Model 95 camera was launched with two separate rolls (a positive/developing agent and a negative) that enabled the image to be developed inside the camera. The film sold out in one day.

1963 The Model 100 folding rangefinder camera was introduced. It featured folding bellows, automatic exposure and took 100-series 72x95mm pack film.

1972 The historic SX-70 folding camera was launched, which didn’t require a peel-apart film. It took a 77x77mm square image with an ISO value of around 160. SX-70 cameras were produced between 1972 and 1981.

1976 The first Polaroid 20×24 cameras were built. Only six models were ever produced. The idea was to demonstrate the quality of Polacolor 2 film, which was about to be launched in the 8×10 format.

1981 The integral 600 film was introduced, which offered ten exposures in 79x79mm and also incorporated a flat ‘PolaPulse’

power pack so the cameras didn’t need a battery.

1982 Polaroid SLR 680 launches. The 680 was an evolution of the SX-70 but had the advantage of using faster speed 600 film, so could be used in lower light. It offered ultrasonic AF or manual focus via a geared wheel.

1986 Polaroid introduced the Spectra camera system, which used a rectangular 92x73mm instead of the square format 600 films.

1996 The Polaroid PDC-2000 is launched as the company’s first digital camera. It came in three editions – tethered, 40MB hard disk and 60MB flash drive – and had an 800×600 pixel resolution.

2016 Polaroid Impossible I-1 camera launched with a new format – it was a Polaroid 600 with the battery moved out of the film pack.

2021 The Polaroid Go is a brand new pocket camera from Polaroid.

The book Polaroid Now: The History and Future of Polaroid Photography, by Steve Crist (with contributions by Oskar Smolokowski and John Reuter), is published by Chronicle Chroma, ISBN: 978-1-7972-0137-5, with an RRP of £26. To find out more go to www.chroniclebooks.com.

Further reading